International Journal of Obesity (2002) 26, 1494–1502

ß 2002 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0307–0565/02 $25.00

www.nature.com/ijo

PAPER

Randomized controlled trial to prevent excessive

weight gain in pregnant women

BA Polley1, RR Wing1* and CJ Sims2

1

University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA; and 2Magee Womens Hospital, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA

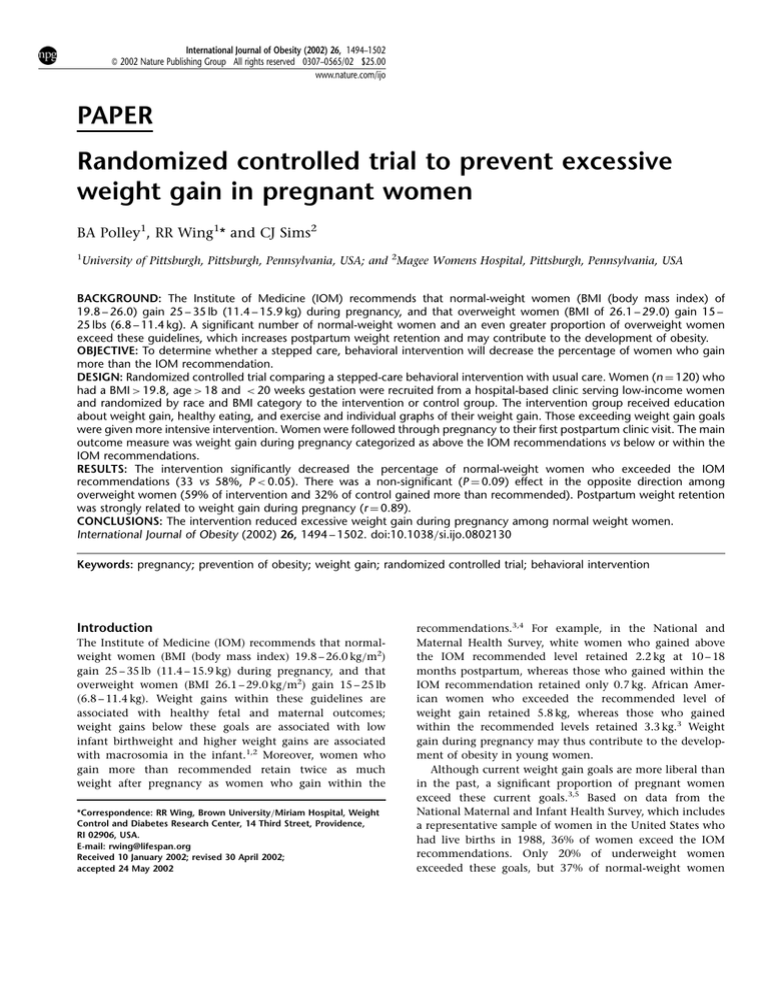

BACKGROUND: The Institute of Medicine (IOM) recommends that normal-weight women (BMI (body mass index) of

19.8 – 26.0) gain 25 – 35 lb (11.4 – 15.9 kg) during pregnancy, and that overweight women (BMI of 26.1 – 29.0) gain 15 –

25 lbs (6.8 – 11.4 kg). A significant number of normal-weight women and an even greater proportion of overweight women

exceed these guidelines, which increases postpartum weight retention and may contribute to the development of obesity.

OBJECTIVE: To determine whether a stepped care, behavioral intervention will decrease the percentage of women who gain

more than the IOM recommendation.

DESIGN: Randomized controlled trial comparing a stepped-care behavioral intervention with usual care. Women (n ¼ 120) who

had a BMI > 19.8, age > 18 and < 20 weeks gestation were recruited from a hospital-based clinic serving low-income women

and randomized by race and BMI category to the intervention or control group. The intervention group received education

about weight gain, healthy eating, and exercise and individual graphs of their weight gain. Those exceeding weight gain goals

were given more intensive intervention. Women were followed through pregnancy to their first postpartum clinic visit. The main

outcome measure was weight gain during pregnancy categorized as above the IOM recommendations vs below or within the

IOM recommendations.

RESULTS: The intervention significantly decreased the percentage of normal-weight women who exceeded the IOM

recommendations (33 vs 58%, P < 0.05). There was a non-significant (P ¼ 0.09) effect in the opposite direction among

overweight women (59% of intervention and 32% of control gained more than recommended). Postpartum weight retention

was strongly related to weight gain during pregnancy (r ¼ 0.89).

CONCLUSIONS: The intervention reduced excessive weight gain during pregnancy among normal weight women.

International Journal of Obesity (2002) 26, 1494 – 1502. doi:10.1038=si.ijo.0802130

Keywords: pregnancy; prevention of obesity; weight gain; randomized controlled trial; behavioral intervention

Introduction

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) recommends that normalweight women (BMI (body mass index) 19.8 – 26.0 kg=m2)

gain 25 – 35 lb (11.4 – 15.9 kg) during pregnancy, and that

overweight women (BMI 26.1 – 29.0 kg=m2) gain 15 – 25 lb

(6.8 – 11.4 kg). Weight gains within these guidelines are

associated with healthy fetal and maternal outcomes;

weight gains below these goals are associated with low

infant birthweight and higher weight gains are associated

with macrosomia in the infant.1,2 Moreover, women who

gain more than recommended retain twice as much

weight after pregnancy as women who gain within the

*Correspondence: RR Wing, Brown University=Miriam Hospital, Weight

Control and Diabetes Research Center, 14 Third Street, Providence,

RI 02906, USA.

E-mail: rwing@lifespan.org

Received 10 January 2002; revised 30 April 2002;

accepted 24 May 2002

recommendations.3,4 For example, in the National and

Maternal Health Survey, white women who gained above

the IOM recommended level retained 2.2 kg at 10 – 18

months postpartum, whereas those who gained within the

IOM recommendation retained only 0.7 kg. African American women who exceeded the recommended level of

weight gain retained 5.8 kg, whereas those who gained

within the recommended levels retained 3.3 kg.3 Weight

gain during pregnancy may thus contribute to the development of obesity in young women.

Although current weight gain goals are more liberal than

in the past, a significant proportion of pregnant women

exceed these current goals.3,5 Based on data from the

National Maternal and Infant Health Survey, which includes

a representative sample of women in the United States who

had live births in 1988, 36% of women exceed the IOM

recommendations. Only 20% of underweight women

exceeded these goals, but 37% of normal-weight women

Prevention of excessive weight gain in pregnancy

BA Polley et al

1495

and 64% of overweight women gained more than recommended.3 Similarly, in a study of over 4000 women from the

University of California, San Francisco Perinatal Database,

23% of underweight women, 49% of normal-weight women,

and 70% of overweight women exceeded the recommendations.5 Thus a substantial proportion of normal-weight

women and an even greater proportion of overweight

women gain more than is recommended.

Weight gain during the first 20 weeks of gestation has

been shown to be predictive of total weight gain;6 – 8 thus, it

may be possible to identify women early in pregnancy who

will exceed the weight gain guidelines and counsel them

about healthy eating and exercise habits to prevent excessive

weight gain during pregnancy. This approach fits with the

Subcommittee on Weight Gain of the National Academy of

Science’s recommendation that deviations from the desired

rate of weight gain be discussed with the woman and

corrective actions such as ‘moderating consumption and

increasing physical activity’ be initiated, as appropriate.1

However, no studies to date have examined the efficacy of

providing education and behavioral strategies related to

healthy eating, moderate exercise and appropriate weight

gain goals as a means of helping women achieve appropriate

rates of pregnancy weight gain.

The goal of the present study was to develop and test a

stepped care behavioral intervention to reduce excessive

weight gain during pregnancy. The intervention provided

education and feedback about weight gain, and stressed

modest exercise and healthy, low-fat eating. We examined

whether, compared with a usual care control group, the

intervention would reduce the number of women who

exceed the IOM recommendations. Because normal-weight

and overweight women have different IOM weight gain

goals and appear to differ in the proportion of women

exceeding these goals, we examined the efficacy of the

intervention for these two groups.

All women signed a consent form approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Pittsburgh Medical

Center and Magee-Womens Hospital. Of the 120 women who

entered the study, 110 (92%) were followed through the end

of their pregnancy; three of the 120 women miscarried, six

moved out of the area, and one asked to withdraw from the

study. An additional five in the intervention group requested

withdrawal from the study but gave consent for continued

monitoring via record review and were retained for all analyses. The final sample of 110 women included 57 in the

treatment group (30 normal weight, 27 overweight) and 53 in

the control group (31 normal weight, 22 overweight). Analysis of variance and chi-square showed no differences between

the treatment and control group on any of the demographic

characteristics summarized in Table 1.

Design and procedures

Women were randomly assigned to the standard care control

group or to the intervention stratified by BMI category

(normal weight vs overweight) and self-reported race (black

vs white). BMI was based on retrospective self-reported

height and weight at last menstrual period with normal

weight defined as BMI ¼ 19.8 to 26.0 and overweight

BMI > 26.0. Although the IOM recommends a weight gain

of 6.8 – 11.3 kg for overweight women (BMI of 26.1 – 29) and

a weight gain of 6.8 kg (with no specified upper limit) for

obese women (BMI > 29), these two groups were collapsed in

the present study and the recommendations for overweight

women were used, as occurs in other research on this topic.5

Standard care

Subjects in the standard prenatal care condition received

only the standard nutrition counseling provided by the

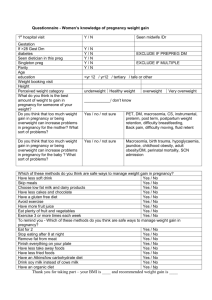

Table 1 Demographic characteristics

Methods

Participants

Pregnant women were recruited before 20 weeks gestation

(mean s.d. ¼ 14.5 3.1 weeks) from an obstetric clinic for

low-income women at a hospital in Pittsburgh, PA, USA.

Subjects were recruited into four cells: normal and overweight, black and white. Underweight women (BMI < 19.8

based on self-reported weight at height at the last menstrual

period) were excluded, as were women younger than 18 y,

those whose first prenatal visit was > 12 weeks gestation, and

those with a high-risk pregnancy (ie drug abuse, chronic

health problems, previous complications during pregnancy,

or current multiple gestation). Of 164 women who were

approached, 120 enrolled in the study. Refusal rates were

higher among black women (28=74 refused) than among

white women (16=90 refused), P < 0.005, and higher in overweight blacks (16=37 refused) than in any of the other three

weight-by-race categories (P < 0.02).

Variable

Distribution

Age (y)

Mean ¼ 25.5 4.8

Race

39% black

61% white

Marital status

31% married

14% separated, divorced or widowed

55% never married

Education

45% high school or less

42% vocational training or some college

9% college graduate

4% graduate training

Employment

57% unemployed

14% trade, service

16% clerical, sales

6% professional

7% other

Childbearing history

47% first pregnancy

30% second pregnancy

17% third pregnancy

6% > third pregnancy

International Journal of Obesity

Prevention of excessive weight gain in pregnancy

BA Polley et al

1496

physicians, nurses, nutritionists and WIC counselors at

Magee-Womens Hospital. This counseling emphasized a

well-balanced dietary intake and advice to take a multivitamin=iron supplement. No information or counseling was

provided by the research staff.

Intervention

The intervention was delivered at regularly scheduled clinic

visits by master’s and doctoral level staff with training in

nutrition or clinical psychology. Shortly after recruitment,

women in the intervention condition were given written and

oral information in the following areas: (a) appropriate

weight gain during pregnancy; (b) exercise during pregnancy;

and (c) healthful eating during pregnancy. Newsletters

prompting healthy eating and exercise habits were mailed

biweekly. In addition, after each clinic visit, women in the

intervention condition were sent a personalized graph of

their weight gain. Women whose weight changes were

within the appropriate ranges were informed that they were

gaining the expected amount of weight and were encouraged

to eat a healthy diet and to have a physically active lifestyle;

those gaining too little were told to check with their physician for guidance outside the scope of this study. Women

whose weight gains exceeded the recommended levels were

given additional individualized nutrition and behavioral

counseling using the format listed in Table 2. A steppedcare approach was used, where the woman was given increasingly structured behavioral goals at each visit if her weight

continued to exceed the recommended levels. The primary

focus of the dietary intervention was on decreasing high-fat

foods, such as fast food items, and substituting healthier

alternatives (fruit and vegetables); if these approaches did

not help the woman achieve the IOM recommended weights,

then a more structured meal plan and individualized calorie

goals were added. The exercise intervention focused on

increasing walking and developing a more active lifestyle

(eg walking rather than driving short distances). Between

clinic visits women were contacted by telephone to discuss

progress towards the goals set at the previous visit.

Measures

Pre-pregnancy weight was the weight at the last menstrual

period, as reported by the participant at the time of recruit-

Table 2 Format of individual counseling sessions

Review of weight gain chart

Assessment of current eating and exercise (ie a 24 h recall or examination

of self-monitoring records), with periodic computerized nutrition analysis

Review of progress toward behavioral goals

Problem-solving

Instruction in the use of behavioral techniques such as stimulus control or

self-monitoring

Goal-setting for eating and exercise behaviors

International Journal of Obesity

ment into this study. Weight was measured at every clinic

visit using a digital or balance beam scale. Total weight gain

was based on self-reported pre-pregnancy weight and weight

at the last clinic visit prior to delivery. For five women, the

last clinic visit was more than one month prior to delivery

and self-reported weight at delivery was used. Postpartum

weight was obtained at the first clinic visit after delivery

(mean s.d. ¼ 8 7.1 weeks); self-reported weight was used

for 14 women; postpartum weight was unavailable for 36

women.

Demographic and weight history information was

obtained at recruitment. Self-report measures of dietary

intake and exercise expenditure were obtained at recruitment, 30 weeks gestation, and 6 weeks postpartum. A short

form of the Block Food Frequency Questionnaire,9 administered by interview, was used to assess consumption of 13

major contributors to fat intake over the past month. This

questionnaire was included to examine changes in intake of

high-fat foods rather than to try to describe the participants’

overall dietary consumption. Energy expenditure was measured using the Paffenbarger Exercise Questionnaire10 by

interview, assessing stair-climbing, walking and recreational

activities over the last week.

Obstetric records were reviewed after delivery to obtain

infant birth weight and complications during pregnancy

and=or delivery.

Statistical analysis

The primary dependent variable was the proportion of

women who exceeded the IOM recommendation. This

was analyzed by logistic regression examining the effect

of treatment group and BMI category on weight gain

category (above IOM recommended level vs below IOM

recommended level). Weeks of gestation at delivery was

used as a covariate. Secondary aims were to assess the

effects of treatment group and BMI category on total

weight gain, weight gain from recruitment to delivery,

postpartum weight loss and weight retention. Analysis of

variance was used for these secondary aims; again weeks of

gestation at delivery was used as a covariate. When significant interactions with weight category were observed,

post hoc analyses were conducted to analyze the effects of

treatment separately in normal-weight and overweight

women. Because pre-pregnant weight differed in normalweight women in the control and intervention groups, prepregnancy weight was covaried in these post hoc analyses.

Analyses were done using an intent-to-treat approach,

including all participants available at the post-pregnancy

or postpartum assessments (Figure 1). Both SAS and SPSS

statistical packages were used.

Results

The flow of participants through the study is shown in

Figure 1. Weight change variables are summarized in Table 3.

Prevention of excessive weight gain in pregnancy

BA Polley et al

1497

Figure 1 Flow of subjects.

Excessive weight gain during pregnancy

Initial analyses examined whether women met weight gain

goals at any time during the pregnancy (ie whether the

women’s weight gain ever exceeded the expected range),

and whether they later ‘recovered’ (ie achieved weight

gains within the expected range). As shown in Table 3,

there was a significant interaction (P ¼ 0.01) between treatment group and BMI category for the percentage of women

Table 3

who exceeded the IOM recommendations at some point

during their pregnancy. Among normal-weight women,

94% of the control group exceeded the recommended level

at some point during pregnancy compared with 63% of

women in the intervention group, P < 0.05. Among overweight women, about two-thirds exceeded the recommended level at some point in their pregnancy regardless

of treatment group, P > 0.4.

Weight changes during pregnancy by treatment group and BMI category, mean s.d. or n (%)

Normal-weight

Overweight

Control

(n ¼ 31)

Intervention

(n ¼ 30)

Control

(n ¼ 22)

Intervention

(n ¼ 27)

22.5 2.0

59 6.9

22.8 1.9

62.1 6.1*

34.1 7.2

91.8 19.6

31.4 6.0

83.6 16.7b,c

Exceeded IOM recommendations at

some point during pregnancy, n (%)

Recovery rates, n (%)

29 (93.5%)

19 (63.3%)*

14 (63.6%)

20 (74.1%)

11 (37.9%)

9 (47.4%)

7 (50.0%)

4 (20.0%)

Total weight gain (kg)

(range, kg)

16.4 4.8

(6.8 – 30.9)

15.4 7.1

(2.7 – 32.7)

10.1 6.2

(70.9 – 26.4)

13.6 7.2b

(1.4 – 29.1)

IOM categories of total weight gain

Exceed IOM recommend, n (%)

Mean gain (kg)

Within IOM recommend, n (%)

Mean gain (kg)

Below IOM recommend, n (%)

Mean gain (kg)

18 (58.1%)

(19.1 kg)

8 (25.8%)

(13.6 kg)

5 (16.1%)

(9.5 kg)

10 (33.3%)*

(23.6 kg)

11 (36.7%)

(13.6 kg)

9 (30.0%)

(8.2 kg)

7 (31.8%)

(17.3 kg)

8 (36.4%)

(10 kg)

7 (31.8%)

(3.6 kg)

16 (59.3%)c

(17.7 kg)

6 (22.2%)

(10.5 kg)

5 (18.5%)

(4.1 kg)

Postpartum weight lossa

Net weight retention, kga

n ¼ 21

79.0 2.4

6.2 4.5

n ¼ 18

79.6 3.5*

4.4 5.4

2

Prepregnancy BMI (kg=m )

Prepregnancy weight (kg)

a

n ¼ 19

79.6 2.7

0.3 7.0

b

c

n ¼ 16

79.1 4.1

3.6 5.6

b

Postpartum weights available for 74 participants and all postpartum weights adjusted for weeks postpartum; main effect of

BMI category, P < 0.001; cinteraction between treatment group and BMI category, P < 0.01.

*Indicates a significant treatment effect for post hoc analyses within each BMI category.

International Journal of Obesity

Prevention of excessive weight gain in pregnancy

BA Polley et al

1498

Women in the intervention group who exceeded the

weight gain pattern were notified that they were gaining

above the IOM recommended levels and were provided with

at least one additional counseling session. The number of

additional sessions ranged from 1 to 11, depending on

whether the women’s weight gain ‘recovered’ or remained

above the guidelines. Of the intervention women who

received additional sessions, normal-weight women

received an average of 3.3 additional sessions and overweight women received an average of 4.8 additional sessions. As shown in Table 3, there was a trend for a

significant treatment group-by-BMI category interaction in

the proportion of women who were able to recover from

excessive weight gain during pregnancy and go on to have a

total weight gain within or below IOM recommendations,

P ¼ 0.07. However, there was no significant effect of treatment when normal-weight and overweight women were

analyzed separately (P > 0.1).

Excessive total weight gain

The primary goal of the intervention was to decrease the

percentage of women who exceeded the IOM guidelines

from pre-pregnancy to the end of pregnancy. As shown in

Figure 2, there was a significant interaction between treatment group and BMI category for excessive weight gain,

P < 0.01. Among normal-weight women, those in the intervention group were significantly less likely than controls to

gain above the IOM recommendations, P < 0.05. Among

overweight women, there was a non-significant effect of

treatment, P ¼ 0.09, but the trend was in the opposite direction. There were no significant effects of race on the percentage of women with excessive weight gains, P > 0.3, nor did

race interact with treatment group or BMI category. Weight

gained before recruitment was strongly related to excessive

weight gain, P < 0.0001 but none of the other demographic

variables predicted excessive weight gain.

Figure 2 Percentage of women whose total weight gain exceeded IOM

recommendations. Overall BMI category by treatment interaction,

P < 0.01; treatment effect among normal-weight women, P < 0.05;

treatment effect among overweight women, P ¼ 0.09.

International Journal of Obesity

Figure 3 Pattern of weight gain at three timepoints: pre-pregnancy

(self-reported), recruitment (mean ¼ 14 weeks), and delivery. The IOM

recommends that overweight women gain 2 lb in the first trimester and

15 – 25 lb (6.8 – 11.4 kg) total, and normal-weight women gain 3.5 lb

(1.6 kg) in the first trimester and 25 – 35 lb (11.4 – 15.9 kg) total.

Continuous analysis of weight gain during pregnancy

Although the intervention affected the percent of normalweight women who exceeded the weight gain goal, Figure 3

shows that the intervention had no significant effects on the

average weight gain from pre-pregnancy to delivery (using

self-reported pre-pregnancy weight) or on weight gain from

recruitment to delivery. On average, normal-weight women

gained 35.0 lb (15.9 kg) from pre-pregnancy to delivery

and overweight women gained 26.5 lb (12.0 kg; P < 0.001).

Weight gains were comparable in black and white women

(31.4 vs 31.0 lb (14.3 vs 14.1 kg)). Weight gain from prepregnancy to delivery was related to pre-pregnancy weight

(P < 0.05), weeks of gestation at delivery (P < 0.05) and the

amount of weight gained before recruitment (P < 0.001), but

was unrelated to any of the baseline demographic variables.

Behavior changes during pregnancy

At recruitment, fat consumption from 13 high-fat foods

averaged 55.9 g per day. All groups decreased their fat consumption from these foods from baseline to 30 weeks, except

normal-weight women in the control condition. There was

no effect of treatment on changes in fat intake from these

foods from recruitment to 30 weeks (P > 0.2), nor was there a

significant treatment by BMI category interaction (P > 0.1).

Twenty women were put on bed rest by their obstetricians; of these women, 11 were put on bed rest prior to the

30-week assessment and were omitted from the exercise

analyses. Mean exercise expenditure at recruitment was

614 kcal=day (2570 kJ=day). There were no differences

between groups in exercise levels at recruitment (P ¼

0.059), but control women tended to be less active than

women in the counseling condition. Changes in exercise

level from recruitment to 30 weeks (P > 0.8) were not related

to treatment condition or BMI. Moreover, collapsing across

Prevention of excessive weight gain in pregnancy

BA Polley et al

1499

treatment groups (n ¼ 110), neither dietary intake nor exercise level was related to the amount of weight gained during

pregnancy nor to whether the women exceeded the IOM

guidelines.

Pregnancy complications and fetal outcomes

Logistic regression was used to examine the effects of

treatment on the percentage of women with low weight

gain, controlling for pre-pregnancy weight and weeks of

gestation at delivery. The percentage of women who gained

less than recommended did not differ significantly for the

intervention vs control group (P > 0.2), nor was the interaction between BMI category and treatment group (P > 0.2)

significant.

Pregnancy outcomes are displayed in Table 4. The number

of obstetric complications was too small for statistical analysis, but does not appear to have been dramatically affected

by the intervention. Similarly, there were no treatment by

BMI category differences in infant birth weight, P > 0.8.

Postpartum weight loss and weight retention

Postpartum weights were available for 74 (67.3%) of the 110

women, who were weighed 8 7.1 (mean s.d.) weeks after

delivery. Postpartum weights were compared with delivery

weights to compute weight loss. The strongest predictor of

postpartum weight loss was the number of weeks postpartum

when weight was measured, P ¼ 0.002; therefore we controlled for weeks postpartum in all analyses of postpartum

weight. As shown in Table 3, the average postpartum weight

loss in each group was about 20 lb (9.1 kg), with no effect of

BMI category or treatment group, nor a significant interaction (all P > 0.4).

Mean postpartum weight retention (postpartum weight

less pre-pregnancy weight) was 8.1 13.1 lb (3.7 5.9 kg),

ranging from 722 to 37 lb (710 to 16.8 kg). Weight retention was strongly correlated with weight gain during pregnancy, r ¼ 0.89, P < 0.001. There was a trend for a significant

interaction between treatment group and BMI category on

weight retention (P ¼ 0.06), with normal-weight women in

the intervention group retaining less than those in the

control group (9.6 vs 13.7 lb; 4.4 kg vs 6.2 kg), and overweight

women in the intervention group retaining more than those

in the control group (7.9 vs 0.66 lb; 3.6 vs 0.3 kg); however,

neither of these differences reached conventional levels of

significance.

Postpartum weight loss and weight retention were also

analyzed by race. There was a significant race effect for

postpartum weight loss (P ¼ 0.01), with black women losing

less weight than white women, with losses of 17.8 and

22.1 lb (8.1 and 10.0 kg), respectively. However, there was

no effect of race on weight retention (postpartum weight less

pre-pregnancy weight), nor did race interact with BMI category or treatment group. Black and white women retained

9.5 and 7.3 lb (4.3 and 3.3 kg), respectively.

Comment

We developed a stepped care, behavioral intervention to

reduce excessive weight gain during pregnancy. The intervention included education and behavioral strategies to

promote healthy, low-fat eating, modest exercise and appropriate weight gain during pregnancy. We found the intervention was effective in reducing the frequency of excessive

weight gain in normal-weight women; whereas 58% of

normal-weight women in the control condition gained

more than 35 lb (15.9 kg) during pregnancy, only 33% of

normal-weight women exceeded this IOM guideline. The

intervention had no significant effect among overweight

women, but the trend was in the opposite direction.

The effectiveness of the intervention among normalweight women appeared to be due primarily to the fact

that fewer women in the intervention group than in the

control group exceeded the expected amount of weight gain

at any point during their pregnancy (63 vs 94%). Such

prevention of excessive weight gain may have resulted

from the basic education about healthy eating and exercise

that was provided to all women in the intervention group

and=or the individual weight graphs they received. There

Table 4 Effect of treatment group and BMI category on pregnancy outcomes

Normal weight

Infant birth weight (g)

Low birth weight (<2500 g), n

Macrosomia (>4000 g), n

Weeks gestation at delivery

Preterm delivery (<36 weeks), n

Cesarean delivery (n)

Pre-eclampsia (n)

Maternal hypertension (n)

Gestational diabetes (n)

Overweight

Control

(n ¼ 31)

Intervention

(n ¼ 30)

Control

(n ¼ 22)

Intervention

(n ¼ 27)

3226.4

3

0

3133.0

4

1

3349.0

2

0

3282.8

1

0

39.5

2

4

0

4

2

39.1

5

2

0

2

0

39.1

3

6

3

4

1

39.4

2

2

2

4

2

International Journal of Obesity

Prevention of excessive weight gain in pregnancy

BA Polley et al

1500

was a trend for the intervention to also help normal-weight

women who exceeded the expected rate of weight gain

‘recover’ and achieve subsequent weight levels within the

IOM guidelines, but this effect was not significant. Thus, the

more intensive stepped-care intervention that occurred

subsequent to excessive weight regain may have been a less

effective component of the intervention than the prevention

component. Since the more intensive stepped-care approach

is the costly aspect of the intervention, further study of

specific components of the intervention is needed.

Whereas the intervention was effective in normal-weight

women, there was a non-significant adverse trend among the

overweight participants. This finding may in part be due to

the low rate of excessive weight gain in the overweight

control group in the present study. While previous studies

suggest that about two-thirds of overweight women may

exceed the IOM guidelines during pregnancy,3,5 only 32%

of the overweight control group in this study exceeded this

level. Of particular note is that only one of nine overweight

black women (11%) in the control condition exceeded the

weight gain goals. Since overweight black women were most

likely to refuse entry into the study, those women who

participated may not have been representative of this population. Alternatively, the lack of a treatment effect among

overweight women may also be related to their longstanding difficulties with weight control, making a minimal

intervention such as the program used here less effective, or

to an unmeasured factor such as dietary restraint, which

could lead to disinhibited overeating if the participants

found the intervention stressful. The differential outcome

for normal and overweight women may also again suggest

that the intervention was more effective for preventing

problems with weight gain than for treating these problems.

Although non-significant, there was a tendency for

normal-weight women in the intervention condition to

gain less than recommended by the IOM. This raises concerns about possible adverse effects of the intervention. The

study was clearly under-powered to examine pregnancy outcomes, but future research should carefully address the safety

of the intervention.

Previous studies suggest that on average women retain

only a small amount of weight post-pregnancy, especially if

potential confounders such as self-report of pre-pregnancy

weight and the effect of aging are taken into consideration.11

In carefully controlled studies, post-pregnancy weight retention in North American women averaged 0.6 – 3.0 kg,12 and

1.4 – 1.6 kg;13 women in the Netherlands retained 1.4 kg14

and women in England retained 70.82 – 0.28 kg11 following

their pregnancy. For a subgroup of women, however, weight

gain during pregnancy may contribute to obesity.11,15 In the

Stockholm Pregnancy and Weight Development Study, 73%

of a sample of severely obese women reported that they

maintained more than 10 kg after pregnancy.15 Over 50%

of Americans are overweight or obese. Most obesity develops

during adulthood and women aged 25 – 44 are at greatest risk

of a major weight gain.16 These large weight gains and the

International Journal of Obesity

resulting development of obesity may relate in part to

pregnancy weight gains. For example, in a study which

followed over 1000 normal-weight women through two

consecutive pregnancies, weight gains above the recommended level during the first pregnancy increased the risk

of being overweight at the time of the second pregnancy

three-fold.17

We found a very strong association (r ¼ 0.89) between

weight gain in pregnancy and postpartum weight retention.

Previous studies have likewise seen such an association with

correlations ranging from 0.36 to 0.84.8,18 – 20 Moreover, in

the present study, the effects of the intervention on postpartum weight retention paralleled the effects of the intervention on excessive weight gain in pregnancy. Specifically,

there was a trend (P ¼ 0.06) for normal-weight women in the

intervention group to retain less than those in the control

group and for overweight women in the intervention group

to retain more weight than those in the control. These

findings support the importance of improving the effectiveness of our intervention for normal-weight women and

developing a better approach for overweight women as a

means of preventing large weight retention postpartum.

Several limitations of the research and its findings should

be noted. Most importantly, the sample size in this study

may have limited our power to detect significant effects of

the intervention. With a sample size of n ¼ 120, we had 0.75

power to detect a difference of 20% between the control and

the intervention group in a one-sided chi-square (a ¼ 0.05),

assuming that 45% of the control group exceeded the IOM

guidelines. Power was limited further by the fact that only

110 of the 120 women completed the study and only 74 were

available for postpartum measurements.

Secondly, this study utilized a lower-income clinic population which faced many barriers to participation in the

program, such as lack of social support (over half were

single), financial hardship (over half were unemployed),

and practical issues such as unreliable transportation for

grocery shopping and access to health care and disruptions

in phone service which interfered with maintaining contact

with the study. Many of the women also faced issues such as

smoking, alcohol and drug use, and coping with an

unplanned pregnancy; this population (and their health

care providers) had more critical concerns than the effect

of excessive weight gain on maternal and infant health.

These women had very limited knowledge about nutrition

and healthful eating and needed intensive education and

counseling; however, their limited resources (eg unreliable

attendance at appointments) made intensive counseling

difficult. Selecting a more adherent population would allow

for a better test of the efficacy of behavioral intervention

during pregnancy.

The intervention used in this study was designed to

minimize risk, and this may have limited its effectiveness.

Participants were initially taught to make healthy, low-fat

choices, but were not prescribed a specific diet or given a

restricted energy intake goal until they had exceeded the

Prevention of excessive weight gain in pregnancy

BA Polley et al

1501

recommended weight at four consecutive clinic visits.

Studies with GDM patients21 – 24 suggest that some energy

restriction can be implemented safely during pregnancy,

although the applicability of these findings to non-diabetic

pregnancies is unclear. This study showed no differences

between conditions in eating or exercise behavior, perhaps

reflecting the limited changes that were obtained, the difficulty of accurately assessing these behaviors,25 and the

limitations of the instruments selected for assessing diet

and activity in the present study. Moreover, data were not

collected on other behaviors that could potentially affect

pregnancy-associated weight changes, including changes in

smoking habits, breast feeding and general lifestyle changes

accompanying pregnancy and motherhood.16

Like most pregnancy studies, we relied on a self-reported

pre-pregnancy weight and for a few cases on self-reported

postpartum weight. Several studies have suggested that such

self-reports are quite accurate, typically underestimating

weight by 1 – 2 kg.17 However, in one study of adolescents,

there was more pronounced under-reporting among the

overweight.27 Thus, self-reported pre-pregnancy weight is a

possible source of error among overweight women, but

should have affected the intervention and control condition

equally.

Weight gain during pregnancy was strongly correlated

with pre-pregnancy weight and with weeks gestation at

delivery. Given this tight biological control, it may be difficult

to influence pregnancy weight gain by lifestyle changes.

Indeed, studies of maternal nutritional supplementation

during pregnancy have found minimal effects on weight

gain, even when supplements of up to 1000 kcal per day are

provided (with notably poor compliance).28,29 This biological

drive, coupled with the numerous competing self-care

demands during pregnancy, may limit the magnitude of

change possible during pregnancy. Thus, a postpartum

approach should also be considered. Lovelady and colleagues30 were able to promote weight loss in newly postpartum

overweight women with a 10 week eating and exercise program, with no detrimental effects on lactation success, and

Leermakers and colleagues31 found that a correspondence

intervention was effective in promoting weight loss in postpartum women. However, during postpartum interventions,

women are busy with infant care and adjustment to motherhood, which may limit the effectiveness of postpartum interventions. Perhaps the most effective approach would be to

begin to educate women during pregnancy about healthy

eating and exercise and attempt to limit the frequency and

extent of excessive pregnancy weight gain, and then continue

such interventions in the postpartum period for those who

have retained excessive amounts of weight.

Our conservative intervention significantly reduced

excessive weight gain among normal-weight women but

not among overweight women. Given that the majority of

childbearing women are normal weight, and that our results

were achieved in a low-SES population with considerable

barriers, this intervention shows promise as a behavioral

method of promoting appropriate weight gain during pregnancy, and helping to prevent the development of long-term

weight problems. Further research is needed to confirm the

efficacy and safety of this type of behavioral intervention for

preventing excessive weight gain in normal-weight women

and to define the key components of the intervention that

are required for its success. In addition, it is important to

develop a more effective way to prevent excessive pregnancy-related weight gain in overweight women.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Cathy DeBranski, RN-C for her help in

recruiting and scheduling participants for this study. This

work was funded by a grant from Magee-Womens Health

Foundation; Magee-Womens Research Institute awarded to

Dr Wing.

References

1 Lederman SA. Recent issues related to nutrition during pregnancy. J Am Coll Nutr 1993; 12: 91 – 100.

2 Parker JD, Abrams B. Prenatal weight gain advice: an examination

of the recent prenatal weight gain recommendations of the

Institute of Medicine. Obstet Gynecol 1992; 79: 664 – 669.

3 Keppel KG, Taffel SM. Pregnancy-related weight gain and retention: implications of the 1990 Institute of Medicine guidelines.

Am J Public Health 1993; 83: 1100 – 1103.

4 Scholl TO, Hediger ML, Schall JI, Ances IG, Smith WK. Gestational weight gain, pregnancy outcome, and postpartum weight

retention. Obstet Gynecol 1995; 86: 423 – 427.

5 Carmichael S, Abrams B, Selvin S. The pattern of maternal weight

gain in women with good pregnancy outcomes. Am J Public

Health 1997; 87: 1984 – 1988.

6 Scholl TO, Hediger ML, Ances IG, Belsky DH, Salmon RW. Weight

gain during pregnancy in adolescence: Predictive ability of early

weight gain. Obstet Gynecol 1990; 75: 948 – 953.

7 Muscati, SK, Gray-Donald, K, Koski, KG. Timing of weight gain

during pregnancy: promoting fetal growth and minimizing

maternal weight retention. Int J Obes 1996; 20: 526 – 532.

8 Rossner S, Ohlin A. Pregnancy as a risk factor for obesity: lessons

from the Stockholm pregnancy and weight development study.

Obes Res 1995; 3(Suppl 2): 267s – 275s.

9 Block G, Clifford C, Naughton MD, Henderson M, McAdams M.

A brief dietary screen for high fat intake. J Nutr Educ 1989; 21:

199 – 207.

10 Paffenbarger RS Jr., Hyde RT, Wing AL, Hsieh C-C. Physical

activity, all-cause mortality, and longevity of college alumni.

New Engl J Med 1986; 314: 605 – 613.

11 Harris, HE, Ellison, GTH, Holliday, M, Lucassen, E. The impact

of pregnancy on the long-term weight gain of primiparous

women in England. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1997; 21:

747 – 755.

12 Smith, DE, Lewis, CE, Caveny, JL, Perkins, LL, Burke, GL, Bild, DE.

Longitudinal changes in adiposity associated with pregnancy.

JAMA 1994; 271: 1747 – 1751.

13 Williamson, DF, Madans, J, Pamuck, E, Flegal, KMk Kendrick, JS,

Serdula, MK. A prospective study of childbearing and 10-year

weight gain in US white women 25 to 45 years of age. Int J Obes

Relat Metab Disord 1994; 18: 561 – 569.

14 Rookus, MA, Rokebrand, P, Burema, J, Deurenberg, P. The effect of

pregnancy on the body mass index 9 months post-partum in 49

women. Int J Obes 1987; 11: 609 – 618.

15 Rossner, S. Pregnancy, weight cycling and weight gain. Int J Obes

1992; 16: 145 – 147.

International Journal of Obesity

Prevention of excessive weight gain in pregnancy

BA Polley et al

1502

16 Williamson, DF, Kahn, HS, Remington, PL, Anda, RF. The 10-year

incidence of overweight and major weight gain in US adults. Arch

Intern Med 1990; 150: 665 – 672.

17 Gunderson, EP, Abrams, B, Selvin, S. The relative importance of

gestational gain and maternal characteristics associated with the

risk of becoming overweight after pregnancy. Int J Obes Relat

Metab Disord 2000; 24: 1660 – 1668.

18 Hunt SC, Daines MM, Adams TD, Heath EM, Williams RR.

Pregnancy weight retention in morbid obesity. Obes Res 1995;

3: 121 – 130.

19 Schauberger CW, Rooney BL, Brimer LM. Factors that

influence weight loss in the puerperium. Obstet Gynecol 1992;

79: 424 – 429.

20 Parham ES, Astrom MF, King SH. The association of pregnancy

weight gain with the mother’s postpartum weight. J Am Diet Assoc

1990; 90: 550 – 554.

21 Algert S, Shragg P, Hollingsworth DR. Moderate caloric restriction

in obese women with gestational diabetes. Obstet Gynecol 1985;

65: 487 – 491.

22 Coetzee EJ, Jackson WPU, Berman PA. Ketonuria in pregnancy —

with special reference to calorie-restricted food intake in obese

diabetics. Diabetes 1980; 29: 177 – 181.

23 Maresh M, Gillmer MDG, Beard RW, Alderson CS, Bloxham BA,

Elkeles RS. The effect of diet and insulin on metabolic profiles of

women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes 1985;

34(Suppl 2): 88 – 93.

International Journal of Obesity

24 Dornhurst A, Nicholls SD, Probst F, et al. Calorie restriction for

treatment of gestational diabetes. Diabetes 1991; 40(Suppl 2):

161 – 164.

25 Lichtman SW, Pisarka, K et al. Discrepancy between self-reported

and actual caloric intake and exercise in obese subjects. New Engl J

Med 1992; 327: 1893 – 1898.

26 Harris HE, Ellison GTH, Clement S. Do the psychosocial and

behavioral changes that accompany motherhood influence the

impact of pregnancy on long-term weight gain. Obstet Gynecol

1999; 20: 65 – 79.

27 Stevens-Simon C, Roghmann KJ, McAnarney ER. Relationship of

self-reported pre-pregnant weight and weight gain during pregnancy to maternal body habitus and age. J Am Diet Assoc 1992;

92: 85 – 87.

28 Adair LS, Pollitt E, Mueller WH. The Bacon Chow study: Effect of

nutritional supplementation on maternal weight and skinfold

thicknesses during pregnancy and lactation. Br J Nutr 1984; 51:

357 – 369.

29 Rush D, Sloan NL, Leighton J et al. Longitudinal study of pregnant women. Am J Clin Nutr 1988; 48: 439 – 483.

30 Lovelady CA, Garner KE, Moreno KL, Williams JP. The effect of

weight loss in overweight, lactating women on the growth of

their infants. New Engl J Med 2000; 342: 449 – 453.

31 Leermakers EA, Anglin K, Wing RR. Reducing postpartum weight

retention through a correspondence intervention. Int J Obes Relat

Metab Disord 1998; 22: 1103 – 1109.