How to Choose a

Leadership Pattern

by Robert Tannenbaum and Warren H. Schmidt

No. 73311

MAY–JUNE 1973

How to Choose a Leadership Pattern

Robert Tannenbaum and Warren H. Schmidt

Since its publication in HBR’s March–April 1958 issue, this article has had such impact and popularity as to warrant its choice as

an “HBR Classic.” Mr. Tannenbaum and Mr. Schmidt succeeded

in capturing in a few succinct pages the main ideas involved in the

question of how managers should lead their organizations. For this

publication, the authors have written a commentary, in which

they look at their article from a 15-year perspective (see page 10.)

“I’m being paid to lead. If I let a lot of other people make the decisions I should be making, then I’m

not worth my salt.”

M “I believe in getting things done. I can’t waste

time calling meetings. Someone has to call the shots

around here, and I think it should be me.”

M “I put most problems into my group’s hands and

leave it to them to carry the ball from there. I serve

merely as a catalyst, mirroring back the people’s

thoughts and feelings so that they can better understand them.”

M “It’s foolish to make decisions oneself on matters

that affect people. I always talk things over with my

subordinates, but I make it clear to them that I’m

the one who has to have the final say.”

M “Once I have decided on a course of action, I do

my best to sell my ideas to my employees.”

Each of these statements represents a point of

view about “good leadership.” Considerable experience, factual data, and theoretical principles could

be cited to support each statement, even though

they seem to be inconsistent when placed together.

Such contradictions point up the dilemma in which

modern managers frequently find themselves.

Mr. Tannenbaum is Professor of the Development of Human

Systems at the Graduate School of Management, University of

California, Los Angeles. He is also a Consulting Editor of the

Journal of Applied Behavioral Science and coauthor (with Irving

Weschler and Fred Massarik) of Leadership and Organization: A

Behavioral Science Approach (New York, McGraw-Hill, 1961).

Mr. Schmidt is also affiliated with the UCLA Graduate School of

Management, where he is Senior Lecturer in Behavioral Science.

Besides writing extensively in the fields of human relations and

leadership and conference planning, Mr. Schmidt wrote the

screenplay for a film, “Is It Always Right to be Right?” which

won an Academy Award in 1970.

M

New Problem

The problem of how modern managers can be

“democratic” in their relations with subordinates and

at the same time maintain the necessary authority and

control in the organizations for which they are responsible has come into focus increasingly in recent years.

Earlier in the century this problem was not so

acutely felt. The successful executive was generally

pictured as possessing intelligence, imagination, initiative, the capacity to make rapid (and generally

wise) decisions, and the ability to inspire subordinates. People tended to think of the world as being

divided into “leaders” and “followers.”

New focus: Gradually, however, from the social

sciences emerged the concept of “group dynamics”

Copyright © 1973 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. All rights reserved.

with its focus on members of the group rather than

solely on the leader. Research efforts of social scientists underscored the importance of employee

involvement and participation in decision making.

Evidence began to challenge the efficiency of highly

directive leadership, and increasing attention was

paid to problems of motivation and human relations.

Through training laboratories in group development that sprang up across the country, many of the

newer notions of leadership began to exert an

impact. These training laboratories were carefully

designed to give people a firsthand experience in full

participation and decision making. The designated

“leaders” deliberately attempted to reduce their

own power and to make group members as responsible as possible for setting their own goals and methods within the laboratory experience.

It was perhaps inevitable that some of the people

who attended the training laboratories regarded this

kind of leadership as being truly “democratic” and

went home with the determination to build fully participative decison making into their own organizations. Whenever their bosses made a decision without

convening a staff meeting, they tended to perceive this

as authoritarian behavior. The true symbol of democratic leadership to some was the meeting—and the

less directed from the top, the more democratic it was.

Some of the more enthusiastic alumni of these

training laboratories began to get the habit of categorizing leader behavior as “democratic” or “authoritarian.” Bosses who made too many decisions

themselves were thought of as authoritarian, and

their directive behavior was often attributed solely

to their personalities.

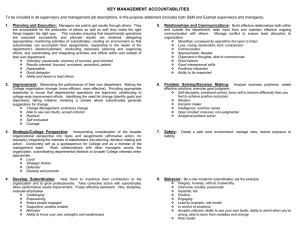

EXHIBIT I

4

New need: The net result of the research findings

and of the human relations training based upon them

has been to call into question the stereotype of an effective leader. Consequently, modern managers often find

themselves in an uncomfortable state of mind.

Often they are not quite sure how to behave; there

are times when they are torn between exerting

“strong” leadership and “permissive” leadership.

Sometimes new knowledge pushes them in one direction (“I should really get the group to help make this

decision”), but at the same time their experience

pushes them in another direction (“I really understand the problem better than the group and therefore

I should make the decision”). They are not sure when

a group decision is really appropriate or when holding

a staff meeting serves merely as a device for avoiding

their own decision-making responsibility.

The purpose of our article is to suggest a framework

which managers may find useful in grappling with

this dilemma. First, we shall look at the different patterns of leadership behavior that managers can choose

from in relating to their subordinates. Then, we shall

turn to some of the questions suggested by this range

of patterns. For instance, how important is it for managers’ subordinates to know what type of leadership

they are using in a situation? What factors should

they consider in deciding on a leadership pattern?

What difference do their long-run objectives make as

compared to their immediate objectives?

Range of Behavior

Exhibit I presents the continuum or range of possible leadership behavior available to managers.

Continuum of Leadership Behavior

HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW

May–June 1973

Each type of action is related to the degree of authority used by the boss and to the amount of freedom

available to subordinates in reaching decisions. The

actions seen on the extreme left characterize managers who maintain a high degree of control while

those seen on the extreme right characterize managers who release a high degree of control. Neither

extreme is absolute; authority and freedom are never

without their limitations.

Now let us look more closely at each of the behavior points occurring along this continuum.

The manager makes the decision and announces

it. In this case the boss identifies a problem, considers alternative solutions, chooses one of them, and

then reports this decision to the subordinates for

implementation. The boss may or may not give consideration to what he or she believes the subordinates will think or feel about the decision; in any

case, no opportunity is provided for them to participate directly in the decision-making process.

Coercion may or may not be used or implied.

The manager “sells” the decision. Here the manager, as before, takes responsibility for identifying

the problem and arriving at a decision. However,

rather than simply announcing it, he or she takes

the additional step of persuading the subordinates to

accept it. In doing so, the boss recognizes the possibility of some resistance among those who will be

faced with the decision, and seeks to reduce this

resistance by indicating, for example, what the

employees have to gain from the decision.

The manager presents ideas, invites questions. Here

the boss who has arrived at a decision and who

seeks acceptance of his or her ideas provides an

opportunity for subordinates to get a fuller explanation of his or her thinking and intentions. After presenting the ideas, the manager invites questions so

that the associates can better understand what he or

she is trying to accomplish. This “give and take”

also enables the manager and the subordinates to

explore more fully the implications of the decision.

The manager presents a tentative decision subject to change. This kind of behavior permits the

subordinates to exert some influence on the decision. The initiative for identifying and diagnosing

the problem remains with the boss. Before meeting

with the staff, the manager has thought the problem

through and arrived at a decision—but only a tentative one. Before finalizing it, he or she presents the

proposed solution for the reaction of those who will

be affected by it. He or she says in effect, “I’d like to

hear what you have to say about this plan that I have

developed. I’ll appreciate your frank reactions but

will reserve for myself the final decision.”

The manager presents the problem, gets suggestions, and then makes the decision. Up to this

HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW

May–June 1973

point the boss has come before the group with a

solution of his or her own. Not so in this case. The

subordinates now get the first chance to suggest

solutions. The manager’s initial role involves identifying the problem. He or she might, for example,

say something of this sort: “We are faced with a

number of complaints from newspapers and the

general public on our service policy. What is wrong

here? What ideas do you have for coming to grips

with this problem?”

The function of the group becomes one of increasing the manager’s repertory of possible solutions to

the problem. The purpose is to capitalize on the

knowledge and experience of those who are on the

“firing line.” From the expanded list of alternatives

developed by the manager and the subordinates, the

manager then selects the solution that he or she

regards as most promising.1

The manager defines the limits and requests the

group to make a decision. At this point the manager passes to the group (possibly taking part as a

member) the right to make decisions. Before doing

so, however, he or she defines the problem to be

solved and the boundaries within which the decision must be made.

An example might be the handling of a parking

problem at a plant. The boss decides that this is

something that should be worked on by the people

involved, so they are called together. Pointing up the

existence of the problem, the boss tells them:

“There is the open field just north of the main

plant which has been designated for additional

employee parking. We can build underground or surface multilevel facilities as long as the cost does not

exceed $100,000. Within these limits we are free to

work out whatever solution makes sense to us. After

we decide on a specific plan, the company will spend

the available money in whatever way we indicate.”

The manager permits the group to make decisions

within prescribed limits. This represents an extreme

degree of group freedom only occasionally encountered in formal organizations, as, for instance, in many

research groups. Here the team of managers or engineers undertakes the identification and diagnosis of

the problem, develops alternative procedures for solving it, and decides on one or more of these alternative

solutions. The only limits directly imposed on the

group by the organization are those specified by the

superior of the team’s boss. If the boss participates in

the decision-making process, deciding in advance to

assist in implementing whatever decision the group

makes, he or she attempts to do so with no more

authority than any other member of the group.

1. For a fuller explanation of this approach, see Leo Moore, “Too Much

Management, Too Little Change,” HBR January–February 1956, p. 41.

5

Key Questions

As the continuum in Exhibit I demonstrates, there

are a number of alternative ways in which managers

can relate themselves to the group or individuals

they are supervising. At the extreme left of the

range, the emphasis is on the manager—on what he

or she is interested in, how he or she sees things,

how he or she feels about them. As we move toward

the subordinate-centered end of the continuum,

however, the focus is increasingly on the subordinates—on what they are interested in, how they

look at things, how they feel about them.

When business leadership is regarded in this way,

a number of questions arise. Let us take four of especial importance:

Can bosses ever relinquish their responsibility by

delegating it to others? Our view is that managers

must expect to be held responsible by their superiors

for the quality of the decisions made, even though

operationally these decisions may have been made

on a group basis. They should, therefore, be ready to

accept whatever risk is involved whenever they delegate decision-making power to subordinates.

Delegation is not a way of “passing the buck.” Also,

it should be emphasized that the amount of freedom

bosses give to subordinates cannot be greater than

the freedom which they themselves have been given

by their own superiors.

Should the manager participate with subordinates once he or she has delegated responsibility to

them? Managers should carefully think over this

question and decide on their role prior to involving

the subordinate group. They should ask if their presence will inhibit or facilitate the problem-solving

process. There may be some instances when they

should leave the group to let it solve the problem for

itself. Typically, however, the boss has useful ideas

to contribute and should function as an additional

member of the group. In the latter instance, it is

important that he or she indicate clearly to the

group that he or she is in a member role rather than

an authority role.

How important is it for the group to recognize

what kind of leadership behavior the boss is

using? It makes a great deal of difference. Many

relationship problems between bosses and subordinates occur because the bosses fail to make clear

how they plan to use their authority. If, for example,

the boss actually intends to make a certain decision,

but the subordinate group gets the impression that

he or she has delegated this authority, considerable

confusion and resentment are likely to follow.

Problems may also occur when the boss uses a

“democratic” facade to conceal the fact that he or

she has already made a decision which he or she

hopes the group will accept as its own. The attempt

6

to “make them think it was their idea in the first

place” is a risky one. We believe that it is highly

important for managers to be honest and clear in

describing what authority they are keeping and what

role they are asking their subordinates to assume in

solving a particular problem.

Can you tell how “democratic” a manager is by the

number of decisions the subordinates make? The

sheer number of decisions is not an accurate index

of the amount of freedom that a subordinate group

enjoys. More important is the significance of the decisions which the boss entrusts to subordinates.

Obviously a decision on how to arrange desks is of an

entirely different order from a decision involving the

introduction of new electronic data-processing equipment. Even though the widest possible limits are

given in dealing with the first issue, the group will

sense no particular degree of responsibility. For a boss

to permit the group to decide equipment policy, even

within rather narrow limits, would reflect a greater

degree of confidence in them on his or her part.

Deciding How to Lead

Now let us turn from the types of leadership which

are possible in a company situation to the question of

what types are practical and desirable. What factors

or forces should a manager consider in deciding how

to manage? Three are of particular importance:

□

□

□

Forces in the manager.

Forces in the subordinates.

Forces in the situation.

We should like briefly to describe these elements

and indicate how they might influence a manager’s

action in a decision-making situation.2 The strength

of each of them will, of course, vary from instance to

instance, but managers who are sensitive to them

can better assess the problems which face them and

determine which mode of leadership behavior is

most appropriate for them.

Forces in the manager: The manager’s behavior

in any given instance will be influenced greatly by

the many forces operating within his or her own personality. Managers will, of course, perceive their

leadership problems in a unique way on the basis of

their background, knowledge, and experience.

Among the important internal forces affecting them

will be the following:

1. Their value system. How strongly do they feel

that individuals should have a share in making the

2. See also Robert Tannenbaum and Fred Massarik, “Participation by

Subordinates in the Managerial Decision-Making Process,” Canadian

Journal of Economics and Political Science, August 1950, p. 413.

HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW

May–June 1973

decisions which affect them? Or, how convinced are

they that the official who is paid to assume responsibility should personally carry the burden of decision making? The strength of their convictions on

questions like these will tend to move managers to

one end or the other of the continuum shown in

Exhibit I. Their behavior will also be influenced by

the relative importance that they attach to organizational efficiency, personal growth of subordinates,

and company profits.3

2. Their confidence in subordinates. Managers

differ greatly in the amount of trust they have in other

people generally, and this carries over to the particular employees they supervise at a given time. In viewing his or her particular group of subordinates, the

manager is likely to consider their knowledge and

competence with respect to the problem. A central

question managers might ask themselves is: “Who is

best qualified to deal with this problem?” Often they

may, justifiably or not, have more confidence in their

own capabilities than in those of subordinates.

3. Their own leadership inclinations. There are

some managers who seem to function more comfortably and naturally as highly directive leaders.

Resolving problems and issuing orders come easily to

them. Other managers seem to operate more comfortably in a team role, where they are continually sharing

many of their functions with their subordinates.

4. Their feelings of security in an uncertain situation. Managers who release control over the decisionmaking process thereby reduce the predictability of the outcome. Some managers have a greater

need than others for predictability and stability in their

environment. This “tolerance for ambiguity” is being

viewed increasingly by psychologists as a key variable

in a person’s manner of dealing with problems.

Managers bring these and other highly personal

variables to each situation they face. If they can see

them as forces which, consciously or unconsciously,

influence their behavior, they can better understand

what makes them prefer to act in a given way. And

understanding this, they can often make themselves

more effective.

Forces in the subordinate: Before deciding how to

lead a certain group, managers will also want to consider a number of forces affecting their subordinates’

behavior. They will want to remember that each

employee, like themselves, is influenced by many personality variables. In addition, each subordinate has a

set of expectations about how the boss should act in

relation to him or her (the phrase “expected behavior”

is one we hear more and more often these days at discussions of leadership and teaching). The better man3. See Chris Argyris, “Top Management Dilemma: Company Needs vs.

Individual Development,” Personnel, September 1955, pp. 123–134.

HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW

May–June 1973

agers understand these factors, the more accurately

they can determine what kind of behavior on their

part will enable subordinates to act most effectively.

Generally speaking, managers can permit subordinates greater freedom if the following essential conditions exist:

If the subordinates have relatively high needs for

independence. (As we all know, people differ greatly

in the amount of direction that they desire.)

□ If the subordinates have a readiness to assume

responsibility for decision making. (Some see additional responsibility as a tribute to their ability; others see it as “passing the buck.”)

□ If they have a relatively high tolerance for ambiguity. (Some employees prefer to have clear-cut

directives given to them; others prefer a wider area

of freedom.)

□ If they are interested in the problem and feel that

it is important.

□ If they understand and identify with the goals of

the organization.

□ If they have the necessary knowledge and experience to deal with the problem.

□ If they have learned to expect to share in decision

making. (Persons who have come to expect strong

leadership and are then suddenly confronted with

the request to share more fully in decision making

are often upset by this new experience. On the other

hand, persons who have enjoyed a considerable

amount of freedom resent bosses who begin to make

all the decisions themselves.)

□

Managers will probably tend to make fuller use of

their own authority if the above conditions do not

exist; at times there may be no realistic alternative

to running a “one-man show.”

The restrictive effect of many of the forces will, of

course, be greatly modified by the general feeling of

confidence which subordinates have in the boss.

Where they have learned to respect and trust the

boss, he or she is free to vary his or her own behavior. The boss will feel certain that he or she will not

be perceived as an authoritarian boss on those occasions when he or she makes decisions alone.

Similarly, the boss will not be seen as using staff

meetings to avoid decision-making responsibility. In

a climate of mutual confidence and respect, people

tend to feel less threatened by deviations from normal practice, which in turn makes possible a higher

degree of flexibility in the whole relationship.

Forces in the situation: In addition to the forces

which exist in managers themselves and in the subordinates, certain characteristics of the general situation will also affect managers’ behavior. Among the

more critical environmental pressures that surround

7

them are those which stem from the organization,

the work group, the nature of the problem, and the

pressures of time. Let us look briefly at each of these:

Type of organization—Like individuals, organizations have values and traditions which inevitably

influence the behavior of the people who work in

them. Managers who are newcomers to a company

quickly discover that certain kinds of behavior are

approved while others are not. They also discover

that to deviate radically from what is generally

accepted is likely to create problems for them.

These values and traditions are communicated in

numerous ways—through job descriptions, policy pronouncements, and public statements by top executives. Some organizations, for example, hold to the

notion that the desirable executive is one who is

dynamic, imaginative, decisive, and persuasive. Other

organizations put more emphasis upon the importance

of the executive’s ability to work effectively with people—human relations skills. The fact that the person’s

superiors have a defined concept of what the good executive should be will very likely push the manager

toward one end or the other of the behavioral range.

In addition to the above, the amount of employee

participation is influenced by such variables as the

size of the working units, their geographical distribution, and the degree of inter- and intra-organizational security required to attain company goals.

For example, the wide geographical dispersion of an

organization may preclude a practical system of participative decision making, even though this would

otherwise be desirable. Similarly, the size of the

working units or the need for keeping plans confidential may make it necessary for the boss to exercise more control than would otherwise be the case.

Factors like these may limit considerably the manager’s ability to function flexibly on the continuum.

Group effectiveness—Before turning decisionmaking responsibility over to a subordinate group,

the boss should consider how effectively its members work together as a unit.

One of the relevant factors here is the experience

the group has had in working together. It can generally be expected that a group which has functioned

for some time will have developed habits of cooperation and thus be able to tackle a problem more effectively than a new group. It can also be expected that

a group of people with similar backgrounds and

interests will work more quickly and easily than people with dissimilar backgrounds, because the communication problems are likely to be less complex.

The degree of confidence that the members have

in their ability to solve problems as a group is also a

key consideration. Finally, such group variables as

cohesiveness, permissiveness, mutual acceptance,

and commonality of purpose will exert subtle but

8

powerful influence on the group’s functioning.

The problem itself—The nature of the problem

may determine what degree of authority should be

delegated by managers to their subordinates.

Obviously, managers will ask themselves whether

subordinates have the kind of knowledge which is

needed. It is possible to do them a real disservice by

assigning a problem that their experience does not

equip them to handle.

Since the problems faced in large or growing

industries increasingly require knowledge of specialists from many different fields, it might be inferred

that the more complex a problem, the more anxious

a manager will be to get some assistance in solving

it. However, this is not always the case. There will

be times when the very complexity of the problem

calls for one person to work it out. For example, if

the manager has most of the background and factual

data relevant to a given issue, it may be easier for

him or her to think it through than to take the time

to fill in the staff on all the pertinent background

information.

The key question to ask, of course, is: “Have I

heard the ideas of everyone who has the necessary

knowledge to make a significant contribution to the

solution of this problem?”

The pressure of time—This is perhaps the most

clearly felt pressure on managers (in spite of the fact

that it may sometimes be imagined). The more that

they feel the need for an immediate decision, the

more difficult it is to involve other people. In organizations which are in a constant state of “crisis”

and “crash programming” one is likely to find managers personally using a high degree of authority

with relatively little delegation to subordinates.

When the time pressure is less intense, however, it

becomes much more possible to bring subordinates

in on the decision-making process.

These, then, are the principal forces that impinge

on managers in any given instance and that tend to

determine their tactical behavior in relation to subordinates. In each case their behavior ideally will be

that which makes possible the most effective

attainment of their immediate goals within the limits facing them.

Long-Run Strategy

As managers work with their organizations on the

problems that come up day to day, their choice of a

leadership pattern is usually limited. They must

take account of the forces just described and, within

the restrictions those factors impose on them, do the

best that they can. But as they look ahead months or

even years, they can shift their thinking from tactics

to large-scale strategy. No longer need they be fetHARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW

May–June 1973

tered by all of the forces mentioned, for they can

view many of them as variables over which they

have some control. They can, for example, gain new

insights or skills for themselves, supply training for

individual subordinates, and provide participative

experiences for their employee group.

In trying to bring about a change in these variables, however, they are faced with a challenging

question: At which point along the continuum

should they act?

Attaining objectives: The answer depends largely on

what they want to accomplish. Let us suppose that they

are interested in the same objectives that most modern

managers seek to attain when they can shift their attention from the pressure of immediate assignments:

1. To raise the level of employee motivation.

2. To increase the readiness of subordinates to

accept change.

3. To improve the quality of all managerial decisions.

4. To develop teamwork and morale.

5. To further the individual development of

employees.

In recent years managers have been deluged with a

flow of advice on how best to achieve these longerrun objectives. It is little wonder that they are often

both bewildered and annoyed. However, there are

some guidelines which they can usefully follow in

making a decision.

Most research and much of the experience of

recent years give a strong factual basis to the theory

that a fairly high degree of subordinate-center behavior is associated with the accomplishment of the five

purposes mentioned.4 This does not mean that managers should always leave all decisions to their assis-

HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW

May–June 1973

tants. To provide the individual or the group with

greater freedom than they are ready for at any given

time may very well tend to generate anxieties and

therefore inhibit rather than facilitate the attainment of desired objectives. But this should not keep

managers from making a continuing effort to confront subordinates with the challenge of freedom.

In summary, there are two implications in the

basic thesis that we have been developing. The first

is that successful leaders are those who are keenly

aware of the forces which are most relevant to their

behavior at any given time. They accurately understand themselves, the individuals and groups they

are dealing with, and the company and broader

social environment in which they operate. And certainly they are able to assess the present readiness

for growth of their subordinates.

But this sensitivity or understanding is not

enough, which brings us to the second implication.

Successful leaders are those who are able to behave

appropriately in the light of these perceptions. If

direction is in order, they are able to direct; if considerable participative freedom is called for, they are

able to provide such freedom.

Thus, successful managers of people can be primarily characterized neither as strong leaders nor as

permissive ones. Rather, they are people who maintain a high batting average in accurately assessing

the forces that determine what their most appropriate behavior at any given time should be and in actually being able to behave accordingly. Being both

insightful and flexible, they are less likely to see the

problems of leadership as a dilemma.

4. For example, see Warren H. Schmidt and Paul C. Buchanan,

Techniques that Produce Teamwork (New London, Arthur C. Croft

Publications, 1954); and Morris S. Viteles, Motivation and Morale in

Industry (New York, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1953).

9

Retrospective Commentary

Since this HBR Classic was first published in 1958,

there have been many changes in organizations and in

the world that have affected leadership patterns. While

the article’s continued popularity attests to its essential validity, we believe it can be reconsidered and

updated to reflect subsequent societal changes and new

management concepts.

The reasons for the article’s continued relevance can

be summarized briefly:

M The article contains insights and perspectives which

mesh well with, and help clarify, the experiences of

managers, other leaders, and students of leadership.

Thus it is useful to individuals in a wide variety of organizations—industrial, governmental, educational, religious, and community.

M The concept of leadership the article defines is

reflected in a continuum of leadership behavior (see

Exhibit I in original article). Rather than offering a

choice between two styles of leadership, democratic or

authoritarian, it sanctions a range of behavior.

M The concept does not dictate to managers but helps

them to analyze their own behavior. The continuum

permits them to review their behavior within a context

of other alternatives, without any style being labeled

right or wrong.

(We have sometimes wondered if we have, perhaps,

made it too easy for anyone to justify his or her style of

leadership. It may be a small step between being nonjudgmental and giving the impression that all behavior

is equally valid and useful. The latter was not our

intention. Indeed, the thrust of our endorsement was

for managers who are insightful in assessing relevant

forces within themselves, others, and situations, and

who can be flexible in responding to these forces.)

In recognizing that our article can be updated, we are

acknowledging that organizations do not exist in a vacuum but are affected by changes that occur in society.

Consider, for example, the implications for organizations of these recent social developments:

>

The youth revolution that expresses distrust and even

contempt for organizations identified with the establishment.

> The civil rights movement that demands all minority groups be given a greater opportunity for participation and influence in the organizational processes.

> The ecology and consumer movements that challenge

the right of managers to make decisions without considering the interest of people outside the organization.

> The increasing national concern with the quality of

working life and its relationship to worker productivity, participation, and satisfaction.

These and other societal changes make effective leadership in this decade a more challenging task, requiring

even greater sensitivity and flexibility than was needed

in the 1950’s. Today’s manager is more likely to deal

with employees who resent being treated as subordinates, who may be highly critical of any organizational

system, who expect to be consulted and to exert influence, and who often stand on the edge of alienation from

the institution that needs their loyalty and commitment. In addition, the manager is frequently confronted

by a highly turbulent, unpredictable environment.

In response to these social pressures, new concepts of

management have emerged in organizations. Open-system theory, with its emphasis on subsystems’ interdependency and on the interaction of an organization

with its environment, has made a powerful impact on

managers’ approach to problems. Organization development has emerged as a new behavioral science

approach to the improvement of individual, group,

organizational, and interorganizational performance. New

research has added to our understanding of motivation in

the work situation. More and more executives have become

concerned with social responsibility and have explored the

feasibility of social audits. And a growing number of organizations, in Europe and in the United States, have conducted

experiments in industrial democracy.

In light of these developments, we submit the following thoughts on how we would rewrite certain

points in our original article.

The article described forces in the manager, subordinates, and the situation as givens, with the leadership

pattern a result of these forces. We would now give more

attention to the interdependency of these forces. For

example, such interdependency occurs in: (a) the interplay between the manager’s confidence in subordinates,

their readiness to assume responsibility, and the level of

group effectiveness; and (b) the impact of the behavior of

the manager on that of subordinates, and vice versa.

In discussing the forces in the situation, we primarily identified organizational phenomena. We would

now include forces lying outside the organization and

would explore the relevant interdependencies between

the organization and its environment.

In the original article, we presented the size of the

rectangle in Exhibit I as a given, with its boundaries

already determined by external forces—in effect, a

closed system. We would now recognize the possibility

of the manager and/or the subordinates taking the initiative to change those boundaries through interaction

with relevant external forces—both within their own

organization and in the larger society.

The article portrayed the manager as the principal

and almost unilateral actor. He or she initiated and

(continued)

10

HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW

May–June 1973

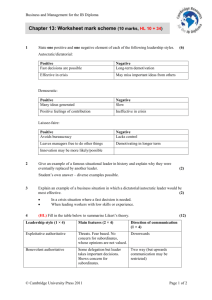

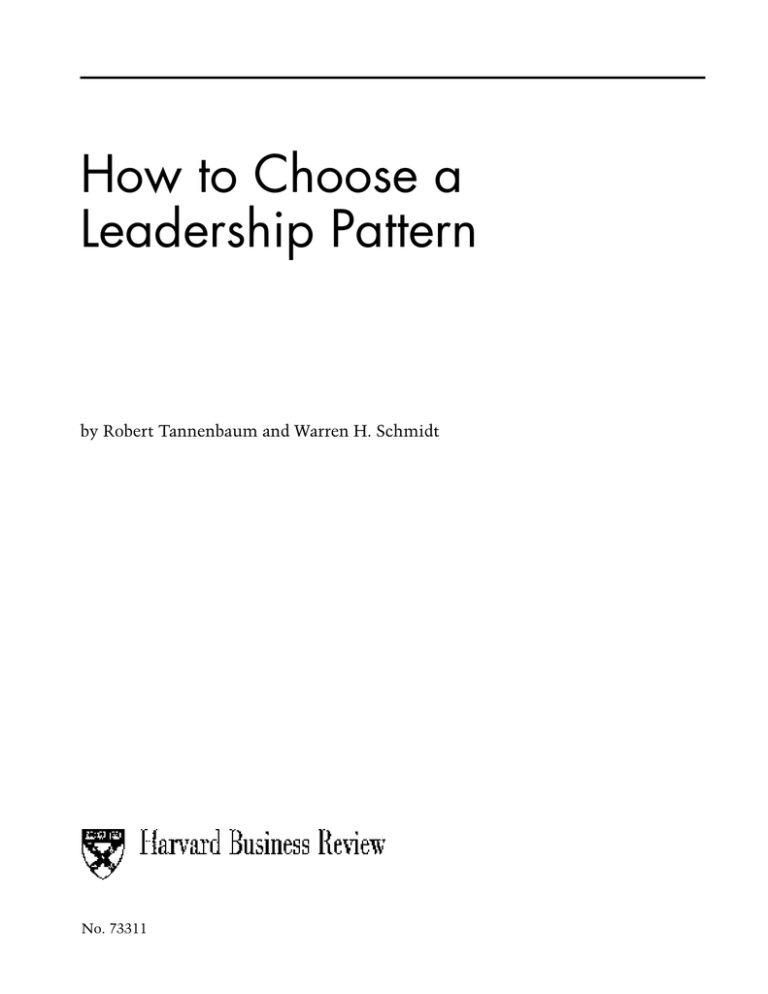

EXHIBIT II

Continuum of Manager-Nonmanager Behavior

Nonmanager power

and influence

Manager power

and influence

Area of freedom

for manager

Area of freedom

for nonmanagers

Manager

able to

make

decision

which

nonmanagers

accept.

TH

E

Manager

must "sell"

his or her

decision

before

gaining

acceptance.

OR

Manager

presents

decision

but must

respond to

questions

from nonmanagers.

R e s u lt

GA

INI

Z AT

ant ma

nag

I O NA

THE

Manager

presents

tentative

decision

subject to

change

after nonmanager

inputs.

Manager

presents

problem,

gets inputs

from nonmanagers,

then

decides.

er and

nonma

nager

b e h av io

Manager

defines

limits within

which

nonmanagers

make

decision.

Manager and

non-managers

jointly make

decision

within limits

defined by

organizational

constraints.

r

L E N V I RO N M E N T

SOCIE

TA L E N V I RO N M E N T

determined group functions, assumed responsibility,

and exercised control. Subordinates made inputs and

assumed power only at the will of the manager.

Although the manager might have taken outside forces

into account, it was he or she who decided where to

operate on the continuum—that is, whether to

announce a decision instead of trying to sell the idea to

subordinates, whether to invite questions, to let subordinates decide an issue, and so on. While the manager

has retained this clear prerogative in many organizations, it has been challenged in others. Even in situations where managers have retained it, however, the

balance in the relationship between managers and subordinates at any given time is arrived at by interaction—direct or indirect—between the two parties.

Although power and its use by managers played a

role in our article, we now realize that our concern

with cooperation and collaboration, common goals,

commitment, trust, and mutual caring limited our

vision with respect to the realities of power. We did not

attempt to deal with unions, other forms of joint worker

action, or with individual workers’ expressions of resistance. Today, we would recognize much more clearly

the power available to all parties and the factors that

underlie the interrelated decisions on whether to use it.

In the original article, we used the terms “manager”

and “subordinate.” We are now uncomfortable with

“subordinate” because of its demeaning, dependencyladen connotations and prefer “nonmanager.” The

titles “manager” and “nonmanager” make the terminological difference functional rather than hierarchical.

We assumed fairly traditional organizational structures in our original article. Now we would alter our

formulation to reflect newer organizational modes

which are slowly emerging, such as industrial democracy, intentional communities, and “phenomenarchy.”* These new modes are based on observations

such as the following:

(continued)

HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW

May–June 1973

11

12

> Both manager and nonmanagers may be governing

forces in their group’s environment, contributing to the

definition of the total area of freedom.

> A group can function without a manager, with managerial functions being shared by group members.

> A group, as a unit, can be delegated authority and

can assume responsibility within a larger organizational context.

The arrows in the exhibit indicate the continual flow

of interdependent influence among systems and people.

The points on the continuum designate the types of

manager and nonmanager behavior that become possible with any given amount of freedom available to

each. The new continuum is both more complex and

more dynamic than the 1958 version, reflecting the

organizational and societal realities of 1973.

Our thoughts on the question of leadership have

prompted us to design a new behavior continuum (see

Exhibit II) in which the total area of freedom shared by

manager and nonmanagers is constantly redefined by interactions between them and the forces in the environment.

*For a description of phenomenarchy, see Will McWhinney,

“Phenomenarchy: A Suggestion for Social Redesign,” Journal of

Applied Behavioral Science, May 1973.

HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW

May–June 1973