National Local Government Biodiversity Strategy

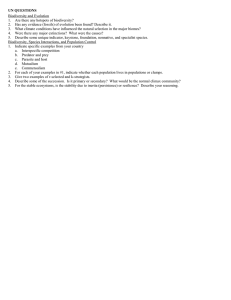

advertisement