1 AJEEP Afghan Media Law Presented by Larry Sokoloff and

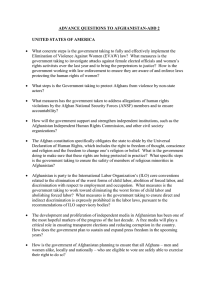

advertisement