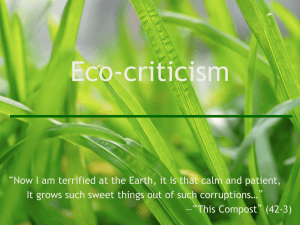

“Nature behaves like a subject”: Human and Nonhuman Relations in

“Nature behaves like a subject”:

Human and Nonhuman Relations in Karen Blixen’s

Out of Africa and Shadows on the Grass

Anna Persson

Student Number: 10418326 rMA Thesis Literary Studies

Supervisor: Dr. Jules Sturm

Second Reader: Prof. Henk van der Liet

Enhver iblandt os vil i sit hjerte føle, hvor rig og forunderlig denne ene ting er: mit liv.

(Karen Blixen “Mit livs mottoer”)

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Theory and Methodology

Ecocriticism

New Materialism and Material Feminism

Approaching Material Ecocriticism

3. Place: Intersections of Landscape, Body, and Identity

Blixen and the (Post-)Colonial Landscape

The Trans-Corporeal Farm

Negotiating Identities in the Time-Space

4. Vivisecting an Ingrained Perception: Human and Nonhuman Animal

Relationships

When the Political and Wild Animal Meet

Disrupting the Dualisms

31

32

35

14

14

19

27

1

5

6

10

12

5. We Have Always Been Intertwined: Actor-Network Relations Within and Beyond the Karen Coffee Company

Mapping Latour

Thinking with the Nonhuman, Thinking of Blixen

46

46

48

6. Conclusion

Works Cited

54

57

1. Introduction

“[A] coffee-plantation is a thing that gets hold of you and does not let you go”

(Karen Blixen Out of Africa )

In this thesis I will examine Karen Blixen’s autobiographical accounts of her seventeen years in Kenya, Out of Africa and Shadows on the Grass from an ecocritical and new materialist perspective . As one of the most prominent authors in the history of Danish literature, the field of research relevant to Blixen covers readings ranging from issues such as gender, self-translation, and national identity to (post)colonialism. The motivation behind the choice of a material ecocritical perspective will become clear, as the reading of Out of Africa and Shadows on the Grass will show how ecocriticism and new materialism intersect with other fields and previous research on Blixen’s work. This theoretical intersection, or cross-fertilization of perspectives, will come to highlight not only the relationship between the theoretical paradigms but also the general overthrowing of binary thinking which permeates Blixen’s writing.

Out of Africa was first published in Danish as Den afrikanske Farm ( The African Farm ) , in 1937, and translated by Blixen herself into English. The English translation was published later that year. The Danish text was published under the name Karen Blixen but for the English text she used the pseudonym Isak Dinesen (Oxfeldt 106). Blixen’s intention was to publish the Danish, Swedish, English and American editions simultaneously. However, the American version was delayed and not published until

1938 (Brantly 73). Shadows on the Grass ( Skygger paa Græsset ) was published in English and

Danish in 1960, two years before Blixen’s death. The scholarship on Shadows on the Grass is not as extensive as that on Out of Africa. While entire books are devoted to explorations of the Out of Africa narrative, Shadows on the Grass is usually mentioned as an appendix to its autobiographical predecessor. Due to the scope of this thesis, I too will take this postscript approach to the text and not explore it as extensively as Out of Africa .

In addition to Blixen’s memoirs, I will also refer to some of the many letters and essays that she wrote during her lifetime. Before continuing, I wish to point out that as much

1

of the scholarship afforded Karen Blixen’s work is published in Danish, Swedish and

Norwegian I will be referring to the author as Karen Blixen throughout rather than using her penname Isak Dinesen. All provided translations of these texts are mine unless otherwise stated.

To summarize the narratives and contextualize these texts, the most convenient thing to do is to turn to Blixen’s biography. Nevertheless, in this setting it is relevant to mention that up until the publication of Blixen’s letters from Africa in 1978, many saw the “objectivity and truthfulness” of Out of Africa to be one of the most appealing features (Brantly 75). However, the publication of her letters showed the creative freedom Blixen took in writing Out of Africa (75). Even so, one of the main scholarly focuses in approaching Out of Africa since the eighties is through: “the nature of Out of

Africa as female autobiography ” (75 emphasis added). The link between Blixen’s real life events and her memoirs is thus still continuously reinstated to this day.

Karen Blixen was born in 1885 in Rungstedlund between Copenhagen and

Helsinore on the Zealand coast of Denmark. As Judith Thurman states in her influential work Isak Dinesen: The Life of Karen Blixen , Blixen was born into a family that she herself perceived as an antithetical union (24). Thurman describes Blixen’s mother’s family, the Westenholzes, as “urban, literate and squeamish” whereas her father’s side, the Dinesens, were country people and cousins to high Danish noblemen (24). In 1912,

Karen Christentze Dinesen and the Swedish baron Bror Blixen-Finecke announced their engagement (Brantly xiii). The following year, funded by Karen Blixen’s family, they travelled to Kenya––then British East Africa––where Bror Blixen was to set up a coffee farm (xiii). The following year the couple married in Mombasa but the marriage only lasted until 1921, when they separated. Karen Blixen was appointed manager in place of Bror Blixen, who was to have nothing to do with the enterprise (Brantly 77).

Following the end of her marriage with Bror Blixen, Karen Blixen entered into a relationship with the British aristocrat, hunter and pilot Denys Finch Hatton and their relationship lasted for over a decade (Susan Hardy Aiken 42-43). It has been argued that the financial hardship that led to Blixen’s loss of the coffee plantation and forced her to leave Africa played a great part in her development as an author (Johannesson 4-

5). Out of Africa was written as a way to mitigate the sorrow of having to leave the place that she had grown to love and she even stated that without the experience of losing the farm, she would not have become a writer (5).

2

Out of Africa is comprised of five sections that are in turn divided into relatively short chapters. Blixen portrays her time at the farm through these anachronistically ordered snapshots–much like short stories–and creates a collage of her time in Kenya.

Shadows on the Grass is divided into four sections and can be seen as a continuation of the

Out of Africa narrative. However, though Blixen makes a creative and spiritual return to

Kenya in this text, it is also an account of the mail correspondence she had with some of the people she encountered there after she returned to Denmark.

Clearly, the critical responses to Out of Africa are diverse and it is not uncomplicated to read the text in a contemporary context. A recent example of an attempt at coming to terms with Out of Africa can be found in the anthology Jeg havde en

Farm i Afrika: æstetik og kulturmøde i Karen Blixens Den Afrikanske Farm 1 (2012). In his essay,”En af de farligste bøger, der nogen sinde er skrevet om Afrika?: Karen Blixen og kolonialismen” 2 Lasse Horne Kjældgaard uses the Kenyan freelance journalist Dominic

Odipo’s commentary on Blixen from the spring of 2006 as a point of departure in his efforts to nuance the debate on Blixen’s work. Odipo claims that: “If one were to draw up a list of the most dangerous foreigners ever to set foot on African soil, Karen Blixen would be right up there competing for honours with the likes of Henry Morton Stanley,

King Leopold’s trail-blazing mercenary” (Odipo 2006). Others, such as Susan C.

Brantly takes into consideration that: “Dinesen’s implied reader is a white racist, most likely a British settler, and this line comes as a jolt to the modern reader who does not think in these terms. Dinesen takes the opportunity to lecture this reader” (89). Brantly’s attempt at fitting Out of Africa into a present day context might seem a little too lenient.

However, it does serve as an example of one side of the debate on Blixen’s work.

There is undoubtedly a complex web of negotiations at play when discussing

Blixen. Firstly, the prominence of the question of identity is clear from the perspective of the names she chose when publishing her works. Secondly, her role as a white woman in colonized Kenya in a British male-dominated world is significant. As the

Danish scholar Dag Heede states, both of these issues in turn tie in with her play with gender identities, both in her own life and in her fictional creations ( Det Umenneskelige

140). Moreover, as Susan Brantly states, Blixen is interested in dualisms in all of her work and the “interaction of opposites” (93). Moreover: “Dinesen often seeks to

1 I had a Farm in Africa: Aesthetics and the meeting of cultures in Karen Blixen’s Out of Africa

2 “One of the most dangerous books ever written about Africa? Karen Blixen and colonialism”

3

undermine the implied hierarchy of the dualism, thus rejecting, for example, the notion that Europe is better than Africa or male is better than female.” (93). And, furthermore:

“[h]ybridism, the ability to experience both sides of the slash, is fraught with peril” (93).

In this thesis I will focus on questions of identity and belonging in relation to the overthrowing of such human/nonhuman and nature/culture juxtapositions that

Brantly describes. In the first chapter I will chart the theoretical foundations of this thesis, which are ecocriticism, new materialism and material feminism. In the second chapter, I will relate these theories to the question of landscape to show how the intersections of the human and the nonhuman in relation to land takes shape in Blixen’s writing. In the third chapter I will discuss nonhuman animals and how these animals function in the shaping of the narrative, but also how they are given space to display their own right to life. I will relate this literary imagery to an essay Blixen wrote against the practice of vivisection in Denmark. In the final chapter, I will tie these different human and nonhuman relations together in connection to Bruno Latour’s Actor-

Network Theory. I will do this to highlight the entanglements of human and nonhuman relationships. Moreover, the Actor-Network Theory will show the transversal relations of both the theoretical concepts discussed and of the various themes at play in the scholarship on Karen Blixen.

Thus, in addressing these issues in the following chapters, some overarching and uniting questions to remember are: how can an ecocritical and new materialist reading or understanding of Blixen’s work unfold further aspects of the previous research on her work? And: how does the bringing together of ecocriticism and new materialism highlight a possible way of thinking beyond the categories of the human and nonhuman in Blixen’s Out of Africa and Shadows on the Grass ?

4

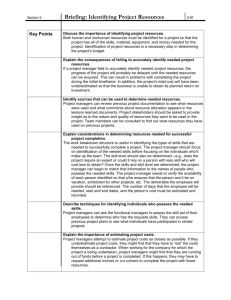

2. Theory and Methodology

[S]ince nature is a word which carries, over a very long period, many of the major variations of human thought - often, in any particular use, only implicitly yet with powerful effect on the character of the argument - it is necessary to be especially aware of its difficulty.

(Raymond Williams, Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society )

This material vitality is me, it predates me, it exceeds me, it postdates me.

(Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: a political ecology of things )

In the following, I will carry out close readings of Blixen’s Out of Africa (1937) and

Shadows on the Grass (1961). Due to limited space the main focus will be on Out of Africa .

Shadows on the Grass will not be discussed in as much depth and will be considered an extension of the Out of Africa narrative. In relation to the texts, there are a couple of elements to bear in mind. Firstly, both texts are autobiographical. Dealing with these texts actualizes the question of what constitutes an autobiography.

3 Even so, I will not problematize these issues other than in passing and I will also pair the reading of

Blixen’s memoirs with non-fictional accounts such as letters and essays. Secondly, both

Out of Africa and Shadows on the Grass are heavily laden with historical references and problematize the colonial processes in Kenya. Much scholarship has been afforded the issue of whether or not Blixen’s writing about Africa should be considered colonial or not. I will consider her position as one of negotiation between a colonial and postcolonial discourse. Even though she engages with the colonial powers and in her profession as head of the coffee farm imposes her power on other people, she still questions the white dominion in Kenya and the repercussions it has for the native population. Bearing these historical and biographical implications in mind, but without yielding to the intentional fallacy in my readings, I will bring in biographical information when necessary in order to contextualize and to develop a more wellrounded reading.

3 See Philippe Lejeune ”The Autobiographical Pact”, Paul de Man ”Autobiography as De-facement”,

Roy Pascal Design and Truth in Autobiography, et cetera.

5

The theoretical foundation of this thesis is that of ecocritical, new materialist and material feminist approaches, or, more concisely put: material ecocriticism.

However, in order not to tell the full theoretical tale twice, I will give a broad introduction to ecocriticism and new materialism respectively. Rather than going into each specific theory for each respective chapter, I will here highlight the ways in which these two theoretical fields intersect. First I wish to make clear what separates ecocriticism and new materialism. Following this, I will point to the convergence of the two and how the theories I will be working with in this thesis overlap in ways that make them highly useful and productive for a reading of Out of Africa and Shadows on the Grass .

Blixen’s two texts were written in a time when environmental issues were in no way as pressing and in need of urgent attention as in the present-day political climate.

Nevertheless, the depiction of varying processes of embodiment and negotiations in relation to the environment–in an ambiguous sense of the word where environment can mean nature, surroundings, a safe place to dwell, a place with threats to the own being, and so on––says something about the ever-changing way in which humans relate to their local and global environment. The primary focus of this thesis is not on the didactic function of literature. However, an ecocritical and new materialist understanding of literature inevitably raises questions about human and nonhuman ontologies that may be relevant in an environmentalist reconfiguration of how we relate to our environment.

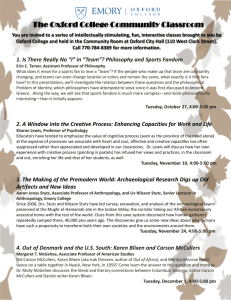

Ecocriticism

Since the beginning of the 1990s ecocriticism has developed into a recognizable paradigm within literary studies. However, as one of the most prominent ecocritics

Lawrence Buell points out in The Future of Environmental Criticism, the roots of the field can be traced back to ancient times, with regards to texts like Genesis and Mayan mythology (2). The term “ecocriticism” itself was originally used by William Rueckert in his 1978 essay “Literature and Ecology: An Experiment in Ecocriticism” (The ISLE

Reader: Ecocriticism, 1993-2003 “Introduction” xiv). In this essay, Rueckert argues that there needs to be a move from the closed literary community to the “biospheric community” which ecology tells us we are a part of, even though we are destroying it

(Rueckert 121). Moreover, he means that the examples he gives from literature are

6

important from a didactic point of view. Discussing William Faulkner’s Absalom,

Absalom!

, he argues that there is “an ecological lesson to learn” (118). In a nutshell then,

Rueckert sees an eco-politically didactic force in literature.

Literature can indeed raise awareness when it comes to ecological issues.

However, William Rueckert’s standpoint appears to be more close to politics than to literature. What Rueckert’s perspective highlights, is that the political environmentalist movement has greatly influenced ecocriticism. While I will not elaborate on concepts such as Deep Ecology or Ecofeminism here, they do deserve to be mentioned. Deep ecology’s “anthropocentric dualism humanity/nature as the ultimate source of antiecological beliefs” is theoretically partly in line with the discussions carried out in the following, as the main point of deep ecology is a move away from anthropocentrism

(Garrard 26 emphasis in original). However, the ecocentrism of the position is not (25).

By replacing anthropocentrism with ecocentrism there is a reinstatement of a different power order rather than a move towards a balance between the human and nonhuman. It may well be that “nature” can benefit from this position more than from an anthropocentric position, but it also highlights there is also an apparent urge to make room for dichotomous relationships between the self and other rather than attempting to bridge the schisms between the human and nonhuman.

Moreover, the androcentric critique in the origin of ecofeminism does not fit within the theoretical framework that will be used here as this critique is based on the notion that the essence of femininity can be traced back to the biological sex and the traditional conception that women have a stronger connection to nature than men do

(Garrard 27). Rather than looking at political environmentalist perspectives as these, I will focus on ecocriticism as a paradigm within literary studies. As the attempt in this thesis is to see how Blixen writes beyond the above dichotomies, neither deep ecology nor traditional ecofeminism fit within the argumentation.

With the above set aside, then, what is ecocriticism? Ursula K. Heise, professor of English at the UCLA Institute of the Environment and Sustainability sets out to describe ecocriticism in the article “The Hitchiker’s Guide to Ecocriticism”. According to Heise, one of the questions that scholars within the field deal with is whether an aesthetic appreciation of nature brings one closer to nature or alienates one from it

(503). Moreover, she exemplifies further issues that arise within the field of ecocriticism,

7

such as: “In what ways do highly evolved and self-aware beings relate to nature? What role does language, literature, and art play in this relation?” (504).

However, before going deeper into the more current state of ecocriticism, a good idea might be to return to one of the early publications, namely the seminal anthology The Ecocriticism Reader: Landmarks in Literary Ecology (1996), and the introduction by one of the editors of the volume, Cheryl Glotfelty. She describes how the mideighties saw the bringing together of scholars who had previously been working in isolation. In 1991 there was a Modern Language Association session organized by

Harold Fromm––Glotfelty’s co-editor––called “Ecocriticism: The Greening of Literary

Studies”. In 1992 the Association for the Study of Literature and the Environment

(ASLE) was founded (xvii ff.). The ASLE expanded and now has chapters all over the world.

4

Following the brief history of the discipline, Glotfelty goes on to define ecocriticism in the following way:

Simply put, ecocriticism is the study of the relationship between literature and the physical environment. Just as feminist criticism examines language and literature from a gender-conscious perspective and Marxist criticism brings an awareness of modes of production and economic class to its reading of texts, ecocriticism takes an earth-centered approach to literary studies. (xviii)

What the above shows according to the sustainability professor Greg Garrard, is that ecocriticism is as much a political endeavor as feminist and Marxist criticism (3).

Further, he states that: “[e]cocritics generally tie their cultural analyses explicitly to a

‘green’ moral and political agenda” (3ff.). Garrard means that: “the emphasis on the moral and political orientation of the ecocritic and the broad specification of the field of study are essential” (4). The broadest definition is that ecocriticism is the study of the relations between the human and nonhuman, covering all of human history, studying what being human entails (5). However, these very inclusive definitions of the field can be narrowed down for a more convenient working definition. On the ASLE website

Cheryl Glotfelty attempts to answer the question of what ecocriticism is. She states that:

4 For example the EASLCE (The European Association for the Study of Literature, Culture and the

Environment), ASLE Japan, ASLE Australia, etc.

8

Ecocriticism takes as its subject the interconnections between nature and culture, specifically the cultural artifacts language and literature. As a critical stance, it has one foot in literature and the other on land; as a theoretical discourse, it negotiates between the human and the nonhuman (Glotfelty ASLE)

Over the years, as seen in The Green Studies Reader: From Romanticism to Ecocriticism (2000), the above stance has come to be accepted as one of the central points of ecocriticism.

Nevertheless, even though the volume brings diverse insight into several aspects of the field, a distinction is made between green studies and ecocriticism. In the book’s glossary, ecocriticism is defined as “the most important branch in green studies” (Coupe 302).

This further complicates finding a precise definition of what ecocriticism exactly is.

However, with a return to Garrard’s Ecocriticism and the write-up on its cover, listing the key concepts of ecocriticism, we are perhaps closer to at least a tentative understanding of what the paradigm covers: “pollution, wilderness, apocalypse, dwelling, animals, earth”.

It is no coincidence that this section was introduced with an epigraph from

Raymond Williams’ Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society . His enigmatic definition of “Nature” is also mentioned in The Green Studies Reader : “Nature is perhaps the most complex word in the language.” (Williams, qtd. in The Green Studies Reader 3).

Paradoxically, and not mentioned in The Green Studies Reader , Williams also describes culture as:

“one of the two or three most complicated words in the English language. This is so partly because of its intricate historical development, in several European languages, but mainly because it has now come to be used for important concepts in several distinct intellectual disciplines and in several distinct and incompatible systems of thought” (87)

The similarity between the Williams’ definitions of nature and culture are striking and highlight how it may be necessary to rethink how different these juxtaposed concepts really are.

It appears that even though ecocriticism is not an all-inclusive field, the boundaries of it become harder to define as it keeps expanding. Just as nature and

9

culture as concepts are complex in themselves, the study of nature in relation to culture and literature is a study with opportunities but also with obstacles. The question of what culture is in relation to nature then automatically arises too. These obstacles are perhaps most clear in the attempts to pin down what is at the center of the ecocritical idiom itself. Ecocriticism may serve as a useful theory when starting to ask questions about human and nonhuman relationships in literature. New materialism, however, may be a useful tool in broadening the questions asked and thus to broaden the perspectives that arise from those questions.

New Materialism and Material Feminism

As the material ecocriticist and foreign language professor Serenella Iovino states in her article “Steps to a Material Ecocriticism: The Recent Literature About the ‘New

Materialisms’ and Its Implications for Ecocritical Theory”, there has in the past years been an explosion of scholarship produced in the field of new materialism. Iovino also stresses the intersection between these new materialisms and the “environmental humanities”, as she labels the field of ecocriticism (134). But what is at the core of these varying material trends?

Introducing new materialism in New Materialisms: Ontology, Agency, and Politics ,

Diana Coole and Samantha Frost describe some of the developments in the dense and long history of materialism. They state that the nineteenth century philosophies of

Marx, Nietzsche and Freud followed a pattern similar to that of the neo-materialist theorists of today, where the natural sciences influenced the social sciences (Coole and

Frost 5). The scope of the project at hand does not allow for an in-depth discussion of the history of materialism, hence, the focus will be on succinctly describing more recent developments. The feminist physicist Karen Barad firmly asserts how she sees the theoretical development of the past decades:

Language has been granted too much power. The linguistic turn, the semiotic turn, the interpretative turn, the cultural turn: it seems that at every turn lately every “thing”–even materiality–is turned into a matter of language or some other form of cultural representation … Discourse matters. Culture matters. There is an important sense in which the only thing that does not seem to matter anymore is matter. (“Posthumanist Performativity” 120)

10

This reconsideration of matter can be seen as a direct response to the prevalent linguistic approaches, following the linguistic and cultural turns.

Diana Coole and Samantha Frost argue that as humans we inescapably live in a material world and our submersion in matter is constant. Moreover:

We are ourselves composed of matter. … In light of this massive materiality, how could we be anything other than materialist? How could we ignore the power of matter and the ways it materializes in our ordinary experiences or fail to acknowledge the primacy of matter in our theories? (1)

What they describe is a pressing need to reevaluate the importance of matter both “in our theories”, but also in, as they first emphasize, “our everyday lives” (1). According to

Coole and Frost, there are indications everywhere of the need for a more materialist approach to fields such as various sociologies, feminism, queer theory and postcolonial studies (2). Serenella Iovino means that prominent scholars such as Bruno Latour,

Donna Haraway and Rosi Braidotti, among others, have paved the way for these new materialist practices in the past twenty years (132).

Even though matter is starting to matter again, there is always something more to it than being just matter (Coole and Frost 9). Materiality is based on “physiochemical processes” but cannot be reduced to that. Instead, there is always more to it, such as relations of force and vitality and that make it active and self-creative. This compels us to re-think the processes of causation and where the capacity for agency can be located and what characterizes this agency (9).

Perhaps one of the most influential works of the past years is Meeting the Universe

Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning (2007) by the abovementioned Karen Barad. The title itself gives a good idea of what is to come and

Barad states that:

This book is about entanglements. To be entangled is not simply to be intertwined with another, as in the joining of separate entities, but to lack an independent, self-contained existence. Existence is not an individual affair.

Individuals do not preexist their interactions; rather, individuals emerge through and as part of their entangled intra-relating (ix)

11

Serenella Iovino very aptly characterizes what Barad describes as “an ongoing process of embodiment” (135). Moreover, Barad uses another rather than the other which highlights how the neo-material thinking moves beyond binarism––in this case away from a fixed otherness––and instead focuses on the unfinished process of embodiment and co-existing, a kind of continuous becoming, if you will.

One of the theories I will be working with in relation to Karen Blixen’s work is trans-corporeality, as described by the literary scholar Stacy Alaimo. The relevance of

Alaimo’s work in the development of the arguments in this thesis lies very much in her use of ecocritical perspectives in relation to new materialism and feminist theory.

Serenella Iovino points towards the importance of Material Feminisms , edited by Stacy

Alaimo and Susan Hekman, in the bringing together of ecocriticism and new materialism. Iovino means that the goal of Material Feminisms is to bridge the gap between matter and “its cultural constructions”. In doing so, reconciliation can be reached between the material and discursive, moving beyond a binary relationship.

Thus, Iovino argues, nature becomes more than a “passive social construct” and can instead be understood as a force with agency, that interacts and alters other elements, such as the human (135).

5

Approaching Material Ecocriticism

Alaimo and Hekman’s anthology serves as an appropriate point of departure in the further understanding of the supposed affinity between ecocriticism and new materialism. One of the definitions of ecocriticism that is particularly noteworthy, was mentioned earlier: “As a critical stance, it has one foot in literature and the other on land; as a theoretical discourse, it negotiates between the human and the nonhuman”

(Glotfelty ASLE). In the previous section, a number of intersections have been illuminated. Firstly, how the focal negotiation of ecocriticism is that between nature and literature. Secondly, in new materialist discourse we are dealing with the convergence between human and nonhuman matter. And thirdly, material feminism, with its

5 For a critical response to the positioning of these new material feminisms see Sara Ahmed “Imaginary

Prohibitions: Some Preliminary Remarks on the Founding Gestures of the ‘New Materialism’”. See also

Iris van der Tuin’s response “Deflationary Logic: Response to Sara Ahmed’s ‘Imaginary Prohibitions:

Some Preliminary Remarks on the Founding Gestures of ‘New Materialism’’”.

12

consideration of the bodily experience of the environment and move away from a strictly discursive practice, highlights yet another divergence of text and body.

While some definitions of ecocriticism appear to impose a nature/culture binary in the reading of literary texts, new materialist practices set out to overcome them. As the matter these theorists discuss is the materiality of all things, creatures and environments, the agency goes beyond human agency. Hence, the environment is taken in to be more than a backdrop for human activity; the agentic forces are everywhere. As

Jane Bennett proposes in Vibrant Matter : “what if we loosened the tie between participation and human language use, encountering the world as a swarm of vibrant materials entering and leaving agentic assemblages? We might then entertain a set of crazy and not so crazy questions” (107). Surely, as Bennet explains, some crazy questions might arise. Nevertheless, the opening up of perception to acknowledge material agency in other matter than the human material might serve this particular ecocritical endeavor very well. By approaching ecocriticism from a new materialist perspective, a more holistic understanding of the entanglements of human and nonhuman materials can come into play.

Serenella Iovino means that the material turn challenges ecocriticism in the need to “explore new narrative dimensions and new forms of narrative agency” (139).

And: “if matter emerges in formations of meanings and bodies on a time-space endowed with an ‘ongoing historicity’, it is almost impossible not to see material agencies as makers of stories” (139). Taking the nonhuman agencies into account means that the difference between subjects and objects is minimized and hence, the shared materiality of all things is raised making all bodies more than mere objects

(Bennett, 13). Having now briefly discussed what a more holistic material ecocriticism might entail, it is time to turn to Blixen’s portrayals of entanglements, assemblage structures and how she moves towards the dissolution of a dualistic subject-object perception of the world.

13

3. Place: Intersections of Landscape, Body, and Identity

What business had I ever to set my heart on Africa? The old continent had done well before my giving it a thought. Might it not have gone on doing so?

(Karen Blixen Shadows on the Grass )

Blixen and the (Post-)Colonial Landscape

Before proceeding to the discussion of the material ecocritical aspects of Blixen’s landscapes, something should be said about some of the more recent criticism on Blixen and the role landscape plays in a post-colonial understanding of the text. Indeed, as

Blixen herself predicted in Out of Africa , her work has “a sort of historical interest” (23).

Some of this “interest” is expressed through enthusiasm for her work whereas some of it is expressed through a reluctance to accept her depictions of Kenya and its people.

In the late 18 th century, Denmark, like many European countries, began a process of nation-building (Larsen 62). An important part of the restructuring of national identity was expressed through the specificity of national landscape (63). In

“The National Landscape–a Cultural European Invention”, Svend Erik Larsen explores this issue in relation to Karen Blixen’s Out of Africa . Larsen is critical of Blixen’s landscape depiction and argues that although she wants to give an image of the landscape as a whole, she only includes the details that make the landscape a totality for her, in itself, and “enable her to experience an identity in relation to the local place”

(Larsen 68). Moreover: “[t]he first thing to notice is that nature is more loaded with subjective purposiveness than with natural factualness ” (68 emphasis added). Undoubtedly, there is much to be said––just as much has already been said––about the colonial aspects of Blixen’s writing. Even though it is instinctively easy to agree with Larsen’s claims about Blixen’s transference of her national identity into the context of the Kenyan landscape, the emphasized sentence in the quote alone requires some further discussion.

In contrast to Larsen’s view, the Danish literary scholar Lasse Horne

Kjældgaard argues that Blixen delivers:

14

et bevis på relevansen af det postkoloniale perspektiv – som en udvidet opmærksomhed på de forskellige kontekster, hvori litteratur bliver læst og får betydning. Karen Blixens værker om Afrika egner sig godt til en indføring i en række postkoloniale problemstillinger, netop fordi de relaterer sig til en kolonial virkelighed – Englands besættelse. (157) 6

The central point in Kjældgaard’s argument is that before drawing the conclusion that

Out of Africa is a dangerous, colonial text, it is important to note that Blixen stood with one foot on each side of the political currents. Out of Africa , Kjældgaard argues, serves as an account of both a partaking in the colonial structures and simultaneously criticizing those same colonial currents of her time (169).

In the very recent work The Creative Dialectic in Karen Blixen’s Essays , Marianne T.

Stecher discusses some of these political currents in Blixen’s essay “Sorte og hvide i

Afrika” (”Blacks and Whites in Africa”) 7 while also relating her discussion to Out of Africa and Shadows on the Grass . Shadows on the Grass portrays the same political landscape as Out of Africa but through the lens of the 1950s, after the Mau Mau uprising (157). This further complicates the understanding of Blixen’s role within the Kenyan political turmoil, as Stecher states: “[it] is, indeed, disappointing that Blixen did not write more about the growing unrest in earlier decades and the colonial conditions that later precipitated the uprising” (160).

In the essay “’I Am a Hottentot’: African Mimicry and Green Xenophilia in

Hans Paasche and Karen Blixen”, forthcoming in the Jahrbuch of the German

Comparative Literature Society, the Danish scholar Peter Mortensen argues that in her critical view on European industrialization, coming from an upper-class background,

Blixen used her self-made “African” persona to test “the limits between colonialism, anti-colonialism and emergent forms of environmentalist and ‘green’ lifestyle reform”(15). One of the main issues Mortensen discusses in his article is how the practices of the less-developed countries are often an assumed solution to the

6 proof of the relevance of a postcolonial perspective – like an extended attention to the several contexts in which literature is read and given meaning. Karen Blixen’s works about Africa introduce a number of post-colonial issues precisely because they relate to a colonial reality – England’s occupation. (157)

7 Originally presented in the form of a talk in the Swedish town Lund and Stockholm in 1938 (Blixen

Samlede Essays 335).

15

industrialized countries’ environmental concerns within green and environmentalist discourse (15). The idea of the subaltern as a source of: “simplicity holism, humility”, and so on, has lead to deep ecologists’ endorsement of East Asian religions as a key to moving away from anthropocentrism (15). However, this has also brought about critique of said environmentalism with regards to romantic primitivism, orientalism and exoticism (15). Mortensen ties these difficulties to Out of Africa and argues that Blixen used her “considerable intercultural insight to construct images of Africa that [she] hoped would stand in redemptive contrast to the humanly and environmentally ruinous beliefs and practices of European modernity” (15-16). Mortensen’s essay allows for the ecocritical perspective to fall into dialogue with the issue of colonialism and the cultural appropriation that Blixen can be said to carry out in her relationship with the native population.

In relation to these issues it is necessary to turn to Blixen’s life events as well as her literary texts. Karen Blixen and her husband Bror Blixen arrived in Kenya, then

British East Africa, in 1914. Funded by their respective families they took possession of a six thousand acre farm. In 1921 Karen Blixen was appointed manager and Bror

Blixen was no longer to have anything to do with the enterprise (Brantly 77). In the following quotation Blixen describes the sharing of the land:

The squatters are the Natives, who with their families hold a few acres on a white man’s farm, and in return have to work for him a certain number of days in the year. My squatters, I think saw the relationship in a different light, for many of them were born on the farm, and their fathers before them, and they very likely regarded me as a sort of superior squatter on their estates ( Out of Africa 14)

The Oxford English Dictionary defines a squatter as: “An unauthorized occupant of land”. The land was, as Blixen points out, appropriated first by natives and then by her.

What serves as a tie between her and the Natives, then, is not their ethnicity or even primarily their working relationship but rather the land itself. As Blixen takes control of their land, the Natives’ relationship to the land shifts and they no longer have to relate only to the estate itself but also to Blixen’s squatting on it.

In the passage from Out of Africa above, the word “superior” is used as a way of describing Blixen’s position on the farm. Contrarily, in Den afrikanske farm the Danish

16

word used for “superior” is “stormægtig” (20). Without taking the comparison between the two texts too far, it is a distinction that should perhaps not be overlooked in this complicated cultural context. “Superior” refers to someone who is higher in rank, position or office ( Oxford English Dictionary ). “Stormægtig” on the other hand, does not simply denote a hierarchical position but also concerns personal qualities. The Danish definition of “stormægtig” includes a description of it as a disparaging adjective, which pertains to dominance and to someone who plays a dominant role within a given system. Moreover, one use of it is to describe an autocratic sovereign ( Ordbog over det danske sprog ).

8 Though this might seem like a minor detail in the passage, it can still be considered an important part in Blixen’s sense of self. Though being high in rank may carry positive connotations, dominance does not. Hence, the self-image presented in the above passage when compared to the Danish text appears to show a discrepancy that highlights a complicated relationship to the taking over of land that she has not traditionally been a part of. The incongruity between the words “superior” and

“stormægtig” in Out of Africa and Den afrikanske farm highlights Blixen’s wavering sense of self in her role as colonizer. Moreover, it also underlines the absence of stability in the interhuman relationship developed through the more-than-human relationship to the land.

One could move beyond the conception of the relationship between Blixen and the native population as a separation based on racial differences, and attempt to perceive of the relationship as emanating form the belonging to the same land. In doing so, an understanding of the belonging to and with the landscape can provide a further perspective on the community living at the farm. In the article “’Where’ your people from girl’: Belonging to Race, Gender and Place Beneath the Clouds ”, Rosalyn Diprose explores such relationships in an Australian postcolonial context. She expresses that:

Part of the task of understanding the communal sharing of meaning in terms of belonging is to acknowledge the significance of embodiment and place in belonging and to reimagine gender and race, not in terms of abstract categories of identity,

8 “(især spøg. ell. nedsæt.) i videre anv., især om person, der har stor indflydelse, formaar meget, spiller en dominerende rolle (inden for en vis kreds), ofte m. bibet. af at vedk. føler magtglæde, sin egen betydning, er stor paa det, optræder stolt, storagtigt; ogs. om person, der virker imponerende ved sin optræden og

(ell.) skikkelse.”

17

but as dynamic aspects of belonging together expressed through community with others (39 emphasis added)

Diprose’s account on the nature of community, with the added stress on embodiment and place, ties in with the concept of trans-corporeality, which is to be discussed in the following. Diprose means that belonging is never an individual or closed event (42).

Rather, she argues that the belonging “must be renewed through other bodies in the present” (42). She emphasizes that belonging is not a question of sharing identity but rather one of finding: “an open and flexible sense of belonging with others and to places” (41). The question of identity thus becomes secondary and the corporeal experience of belonging is what is brought to the fore. Through these processes of embodiment, it becomes unclear what meaning is developed through oneself and what meaning comes from “the world of the other” (41). These processes in turn create a sense of belonging together and create a way of sharing meaning (43). Diprose’s account can be further developed through Stacy Alaimo argument that in the understanding of race as a social category, the perspective of understanding bodies in relation to how they are transformed by their encounters with “places, substances, and, forces” is overlooked ( Bodily Natures 61). Furthermore, Alaimo argues that:

“Environmental justice movements epitomize a trans-corporeal materiality, a conception of the body that is neither essentialist, nor genetically determined … but rather a body in which social power and material/geographic agencies intra-act” (63).

Thinking of the colonial aspects in relation to the environmental humanities opens for new ways of thinking of colonial environments and how the sharing of the land and life alters the material bodies. These alterations in turn change the relationship with the one’s own self and others.

Diprose’s and Alaimo’s accounts stand in stark contrast to such harsh criticism of Blixen as, for example, that of Dominic Odipo. Even so, their accounts of belonging and intra-action tie to other processes of embodiment. Thus, they highlight how the bodily experiences in relation to landscape and community tie in with the colonial aspects of the relationship between Blixen, the native population and their environment. Bearing the colonial, the critique of the colonial and post-colonial intersection in mind it is time to explore further webs of negotiations of identity, embodiment and belonging.

18

The Trans-Corporeal Farm

In the analysis of Blixen’s landscapes, the abovementioned Svend Erik Larsen’s view on her writing serves as a fruitful point of departure––or more critically put––point to depart from . As previously emphasized, Larsen means that Blixen’s nature is more loaded with subjective utility than with natural facts (68). Larsen thus suggests a dichotomous relationship between the landscape and the individual, as though there are natural facts and subjective experiences that do not comingle. However, the Danish scholar Jette Lyndbo Levy sees Out of Africa in a different light:

Mødet med Afrika beskrives som en bevægelse fra at være inde, inde i et hus, inde i en overciviliseret kultur, der har mistet sin mening og sine udfordringer, til at komme ud i en rig og voldsom natur og ud til et møde med en kultur, hvor modsætningen mellem natur og kultur, akkurat som modsætningen mellem Gud og Djævlen, ikke eksisterer. ( Nordisk Kvindelitteraturhistorie ) 9

The notion of trans-corporeality ties in with the break Lyndbo Levy suggests in the binary opposition of nature and culture. Moreover, with a return to the environmental concerns and anti-industrialization aspects of Karen Blixen’s writing, Lawrence Buell’s account of how humans relate to the concept of space is highly relevant. He claims that:

“an awakened sense of physical location and of belonging to some sort of place-based community have a great deal to do with activating environmental concern” ( Writing for an Endangered World 56). This connectedness to the landscape in turn, also ties in with the trans-corporeal. In Bodily Natures: Science, Environment, and the Material Self , Stacy

Alaimo explains how her conception of trans-corporeality can be conceived of. In the development of her argument she borrows the words of Harold Fromm: “’The environment’ as we now apprehend it, runs right through us in endless waves” and that the environment “looks more and more to be the very substance of human existence in the world” (qtd. in Alaimo 11).

9 “The encounter with Africa is described as a movement from being inside; inside an overly civilized culture which has lost its meaning and its challenges, to coming out into a rich and violent nature and out to a meeting with a culture where the opposition between nature and culture, just like the opposition between God and the Devil, do not exist.” ( Nordisk Kvindelitteraturhistoria )

19

Stacy Alaimo uses the concept of trans-corporeality recurrently. As a starting point, she draws on, among others, the philosophy professor Gail Weiss’ discussion on intercorporeality in Embodiment as Intercorporeality (1999). Weiss argues that:

To describe embodiment as intercorporeality is to emphasize that the experience of being embodied is never a private affair, but is always already mediated by our continual interactions with other human and nonhuman bodies. Acknowledging and addressing the multiple corporeal exchanges that continually take place in our everyday lives, demands a corresponding recognition of the ongoing construction and reconstruction of our bodies and body images (5 -6.)

She means that this in turn will open up possibilities for widening the social, political, and ethical domains (6). What is stressed in Weiss’ text then, is that the body is always also tied to the social body. The theology professor Ola Sigurdson’s draws on Weiss’s ideas and describes these ties. He states that: “the individual’s body does not become social, but always already is social as such” (246-247 emphasis in original). Nevertheless, even though Stacy Alaimo draws on Gail Weiss’ ideas, she expands them:

Imagining human corporeality as trans-corporeality in which the human is always intermeshed with the more-than-human world, underlines the extent to which the corporeal substance of the human is ultimately inseparable from “the environment” (“Trans-corporeal Feminisms” 238).

Moreover, she states that trans-corporeality is “a theoretical site” where “corporeal theories and environmental theories meet and mingle in productive ways” (238). What

Alaimo’s definition offers is the opening up of an “epistemological time-space” (253).

The focus for Alaimo thus lies in the understanding of the trans-corporeal as something more than the intertwinement of the private and public. Rather, by using terms such as

“theoretical site” and “epistemological time-space” it appears she is talking about not only overcoming a gap between public and private, but also reaching for a conceptual understanding of the body as entangled with its surroundings, whatever these surroundings may be. Pertaining to current issues in the globalized world, this entanglement is not only epistemological but also political and social.

20

Some non-material feminists might argue that the process of reevaluating the importance of the body and matter is an essentialist endeavor. However, it is important to remember that material feminists do not suggest that natures or bodies exist “prior to discourse”; rather, they think of materiality as connected to several kinds of power and knowledge, some “being more or less ‘cultural’, and some more or less ‘natural’” (243).

Alaimo argues that the trans-corporeal can “help us to imagine an epistemological time-space in which, because they are always acting and being acted upon, human bodies and non-human natures transform, unfold, and thereby resist categorization” (“Trans-Corporeal Feminisms” 253). But how, then, does the concept of the trans-corporeal translate into Out of Africa and Shadows on the Grass , and how does it function in the embodied perceptions of selfhood and identity in the text?

The intersection of the human and nonhuman comes to the fore as Blixen experiences the landscape as a consuming force in relation to which she finds herself in a position of negotiation:

I was young, and by instinct of self-preservation I had to collect my energy on something, if I were not to be whirled away in the dust of farm-roads, or the smoke on the plain. I began in the evenings to write stories, fairy-tales, and romances, that would take my mind a long way off. (42)

Blixen describes the writing process as a way of resisting being devoured by the landscape. By placing herself in opposition to the surrounding landscape, she can be said to voice an understanding of a divide between nature and culture. The consumption that she tries to avoid through writing suggests that the dusty roads would consume her body and mind. Writing, however, would transport her mind “a long way off”. Even though there is a move towards a Cartesian separation of body and mind in this passage, there is also a suggestion that this opposition is not static. It appears that

Blixen conceives of the landscape as an entity in possession of agency and force, which she must either face or attempt to escape through her writing. Alaimo states that:

“Trans-corporeal material ethics takes place in a ‘post-human space’” ( Trans-Corporeal

Feminisms 253). Alaimo then quotes the sociologist and philosopher Andrew Pickering’s

The Mangle of Practice , in which he describes this space as one: “in which the human actors are still there but now inextricably entangled with the nonhuman, no longer at the

21

center of the action and calling the shots . The world makes us in one and the same process as we make the world” (26 emphasis added). This quote highlights the lack of control that

Blixen describes in her relationship to the landscape. As a resistance to the whirling winds and dust of the roads, she turns to a practice that epitomizes the concept of culture: writing. Blixen highlights the agency of the landscape and how its actions are just as unpredictable as human actions. This suggests that resistance is necessary for

Blixen not to be submerged in her surroundings. The form of this submersion is not clearly stipulated in this passage. However, the interlocking of the own body with the land suggests an opening up of an epistemological time-space of the type that Stacy

Alaimo describes.

The bodily connection to the land is described in relation to death, both in Out of Africa and Shadows on the Grass . In Out of Africa Blixen contemplates what she would want her own burial to be like: “I kept on believing I should come to lay my bones in

Africa. For this firm faith I had no other foundation, or no other reason, than my complete incompetence to imagine anything else” (239). Similarly, she describes in

Shadows on the Grass how:

Most of the immigrants had come to Africa, and had stayed on there because they like their African existence better than their existence at home, would rather ride a horse than go in a car and rather make up their own campfire rather than turn on the central heating. Like me they wished to lay their bones in African soil.

(12)

The significance of the consumption of the body after death recurs when Denys Finch-

Hatton is buried, with more vivid imagery than in the above quotations:

As [the coffin] was placed in the grave, the country changed and became the setting for it, as still as itself; the hills stood up gravely, they knew and understood what we were doing in them; after a little while they themselves took charge of the ceremony, it was an action between them and him, and the people present became a party of very small lookers-on in the landscape. (256)

22

The two first quotations show how Blixen and her fellow Europeans express an urge to be united with this land to which they have relocated. In the case of Finch-Hatton’s burial ceremony, this unity is described through what Blixen sees as a responsive action as the body is lowered into the ground. The consummation of the body can be connected to the funeral practices of both English-speaking countries and Denmark:

“Earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust” ( Book of Common Prayer ), and in Danish: “Af jord er du kommet, til jord skal du blive, af jord skal du igen opstå” ( Gyldendals åbne

Encyklopædi ).

10 This earthly connection ties in with what Stacy Alaimo describes as the

“most palpable example of trans-corporeality”, that of food and eating (“Trans-

Corporeal Feminisms” 253). Though at first it might appear slightly morbid to compare eating to the decomposition of a corpse, it highlights the “traffic between bodies and natures” (253). Moreover, in the case of Finch-Hatton’s burial, the focus is on the fusion of the body and the environment, rather than a spiritual synthesis with God.

Nevertheless, the fact that the scene is portrayed as an action between “him” and the hills, and not between his body and the hills, makes it apparent that Blixen envisions a unity of body and mind rather than a Cartesian perception of the mind as separated from the body, even after death.

This is equally the case in Blixen’s own desire to have her bones buried in

Kenyan soil, without really being able to pinpoint from where exactly this desire derives. Even though the Christian spiritual element and the idea of eternal life might play some part in this, it is not articulated in the text. Rather, an understanding of the bodily immersion in the soil can be seen as a manifestation of the intertwinement with other life that she feels in her practices of living. Rosi Braidotti notes in “The Politics of

‘Life Itself’ and New Ways of Dying” that a nonanthropocentric view shows a “love for

Life as a cosmic force and the desire to depersonalize subjective life-and-death” (210).

Moreover, Braidotti states that: “This is just one life, not my life. The life in ‘me’ does not answer to my name: ‘I’ is just passing” (210 emphasis in original). New materialism is nonanthropocentric in its consideration of the vibrancy of all matter. As the sociologist Myra J. Hird argues: “[n]ew materialism has for some time moved towards an understanding of matter as a complex open system subject to emergent properties.”

(“Feminist Matters” 226). What the Braidotti quotation highlights then, is how this

10 ”You have come from the earth, you will become earth, you will rise from the earth” ( Gyldendals åbne

Encyklopædi ).

23

open system moves beyond the subject-object opposition, considering life as a force that can flow in and out of a larger system of material agency. By taking into account the agency of the land, the process of synthesis moves beyond the spiritual aspects of dying and is portrayed as a process of material force (which may well give a sense of spiritual belonging to the land but it is not the focal point). As Blixen observes at Finch-Hatton’s interment: “Now Africa received him, and would change him, and make him one with herself” ( Out of Africa 280). Indeed, as Susan Hardy Aiken notes, Blixen often portrays:

“an unmooring and carrying across of the polar terms of the imperial grammar, an intermingling of ‘I’ and ‘Africa’” ( Isak Dinesen and the Engendering of Narrative 210-211 emphasis in original). This intermingling of “I” and “Africa” that Hardy Aiken describes shows how the dissolution of the subject dominance over the land permeates the practices on the farm and transfers into the events of the everyday life.

One of the most cited passages from Out of Africa is the opening: “I had a farm in

Africa, at the foot of the Ngong Hills” (9). Following this is a detailed description of the vivacious landscape. In the relation to the landscape Blixen describes how:

The civilized people have lost their aptitude for stillness, and must take lessons in silence from the wild before they are accepted by it. The art of moving gently, without suddenness, is the first to be studied by the hunter, and more so by the hunter with the camera. Hunters cannot have their own way, they must fall in with the wind, and the colours and smells of the landscape, and they must make the tempo of the ensemble their own. (17)

Although this passage initially portrays a dichotomization of nature and culture, this vision moves towards a biocentric perception of what surrounds Blixen. Even though this passage centers on one’s relation to animals and avoiding scaring them off, the strategy for doing so still resounds with the “unmooring and carrying across of the polar terms of the imperial grammar” that Hardy Aiken describes above. By refusing the position of the “I” as subject and “Africa” as object, there is a move towards a transcorporeal perception where the human mutst move with the surroundings rather than through them.

The lack of isolation between the “cultural” corporeal and “natural” landscape and the move towards a merging of the two can be described as a need to conceive of

24

nature as something that is not merely a passive backdrop. Alaimo argues that: “to understand the human body as something other than a blank slate awaiting the inscription of culture, we must reconceptualize bodies and natures in ways that recognize their actions” (Alaimo “Trans-Corporeal Feminisms” 244-245). Moreover, the permeability of the body and the landscape can be described in the feminist philosopher Nancy Tuana’s terms of a viscous porosity accompanying the quest for falling in with the wind and making “the tempo of the ensemble” one’s own Tuana discusses this concept in an article on the impact of Hurricane Katrina. Referring to the gruesome effects Katrina had on New Orleans, she describes how an “interactionalist ontology eschews the type of unity and continuity celebrated in traditional Western metaphysics” (“Viscous Porosity” 188). She argues that bodies and sexes are not fixed entities but rather evolving and fluid (189). The passage from Out of Africa highlights this particular permeability and the impact one’s actions have on what contains one’s body.

In order to approach nature and be accepted by it, the human being needs to adapt.

What is more, Blixen does not only highlight an acceptance of the human within the nonhuman realm but also stresses that the hunters and photographers need to “make the tempo of the ensemble their own” (17). Conceiving of these relationship in terms of an ensemble implies a balanced relationship as opposed to one where the human force has dominion over nature or vice versa. The trans-corporeal can thus be considered an astute way of describing Blixen’s own perception of her surroundings as well as the:

“agency of materiality and the porosity of entities” (Tuana 191). Blixen moves away from a conception of isolated units and instead embraces an understanding of the interaction of said entities in the narrative.

Flying with Denys Finch-Hatton: A Divergence from the Time-Space

Even though Blixen portrays the landscape as a devouring force and expresses traits of the trans-corporeal in her writing, she also experiences the landscape from an angle that changes the bodily understanding of the land, namely above ground in the plane with Denys Finch-Hatton. Finch-Hatton was Blixen’s lover, who would come and go as he liked on the farm (Selboe “Stemme og antropologi” 21). The relationship followed the end of her marriage with Bror Blixen, and their relationship lasted for over a decade (Hardy Aiken 42-43). Finch-Hatton’s was a pilot and he was killed when his plane crashed on May 14, 1931 (44). Before this tragic event, however, he took Blixen

25

flying. Blixen describes the flying as “the greatest, the most transporting pleasure of my life on the farm” ( Out of Africa 161). “Transporting” in this instance carries both the physical meaning of being moved from one place to another, as well as the figurative meaning of an emotional relocation. Furthermore, this sense of relocation also pertains to a reevaluation of the relationship to the land.

In connection to how Blixen’s landscapes have been discussed above, it is interesting to see how the relationship changes when the plane takes off. As Tone

Selboe states in Kunst og erfaring: En studie i Karen Blixen forfatterskap , Blixen’s view on flying is not restricted to Out of Africa ; rather: “[g]jennom alle Blixens tekster er flukt og ønske om vinger knyttet til liv og håp; det er den ultimate menneskelige lengsel, et hybrislignende ønske om å bli Gud” (63).

11 Blixen describes this herself: “Every time that I have gone up in an aeroplane and looking down have realized that I was free of the ground, I have had the consciousness of a great new discovery. ‘I see,’ I have thought.

‘This was the idea. And now I understand everything.’” ( Out of Africa 161). This description of the flight encompasses several aspects of the understanding of the relationship between the body, identity and landscape. Firstly, the realization of being

“free of the ground” suggests a kind of trans-corporeal embodiment and understanding of existence, preceding the description of the flight. The prerequisite for the dissolution of the trans-corporeal body is that the body is no longer tied to the land. As this separation occurs, the intertwinement with the land is dissolved. This release, in turn, creates a new awareness of the construction of the landscape. From a material feminist point of view, Blixen, in her ties to the landscape and the transgression of the boundary between body and landscape, shows how the body becomes “more than a site of cultural inscription” (Alaimo “Protesting Bodies” 15). However, during the flight, the body is not nearly as closely tied to the landscape as in, for example, the passage where

Blixen describes the writing as a way of resisting the consuming force of the land.

Instead, the flight allows for a reevaluation of the connection to the landscape. Again,

Selboe:

Tilsvarende er intimiteten med dyrene en nærhet basert på frivillighet og avstand

… Avstanden er nettopp det som gjør sammenføyningen mulig, enten det gjelder

11 ”In all of Blixen’s texts, flying and the wish for wings is tied to life and hope; it is the ultimate human longing, a hubris-like wish to be God” ( Art and Experience 63).

26

Blixens forhold til Denys eller antilopen Lullus forhold til farmen. ( Kunst og erfaring

63) 12

This bringing together that Selboe describes can be productively extended to also include the understanding of the landscape and the trans-corporeal relationship to the landscape.

As the plane begins to descend the land, the tie to the land is reestablished: “We had been flying high, now we went down, and as we sank our own shade, dark blue floated under us upon the light blue lake.” (162). The eye is the central figure in this passage as Blixen observes herself from the outside while the plane and its shadow, causes a group of flamingos to spread across the lake. This highlights how the human impact and nonhuman response to that impact increase as they approach the ground.

However, not until they land, and the shadows of their own bodies intermingle on the same earth as those of the Masai, is the trans-corporeal relationship to the landscape regained, all in the light of shifting closeness, its voluntary nature and distance.

Negotiating Identities in the Time-Space

The instability Blixen displays in her portrayal of the human and the more-than-human landscape can be compared to her own position as farm owner in Kenya. Despite the critique of the colonial aspects of Blixen’s work, there were “limits to the extent she exploited the squatters” (Brantly 77). The developer who bought the farm in 1931 claimed that Blixen’s “stubborn devotion to the Africans” played a part in the farm’s downfall (Brantly 77). Brantly argues that even though Blixen was in a position of power in colonized Africa she maintained a critical perspective on the process and did not partake in the exploitation of the indigenous population to the same extent as other colonizers. However, while this might cast an ameliorating light on Blixen’s colonial activity, it does so only by comparison to the gruesome practices of other Europeans, in particular the British. Nonetheless, with regards to questions of identity and embodiment the quotation is useful in so far as it shows how Blixen embraces a position of negotiation between the prevalent colonizing power and the colonized population.

12 ”Correspondingly, the intimacy with the animals is a closeness based on voluntariness and distance … The distance is exactly what makes the joining possible, regardless of whether it is about Blixen’s relationship to

Denys or the gazelle Lulu’s relationship to the farm” ( Art and Experience 63).

27

The merit of Rosalyn Diprose’s work in relation to these negotiating strategies is that she allows for an understanding of the interhuman terms of belonging together rather than separating groups and entities based on race and gender. In doing so, the search for mitigating literary imagery, or imagery that counters the depiction of the native looses its role. Instead, this “belonging together” takes into account the agency and significance of everyone living on the farm.

A further aspect of Blixen’s negotiating strategies to consider is her position as a woman in the colonies. Selboe describes Blixen’s position as her being: overhodet på farmen, men ikke man, hun er en hvit kvinne, men ikke britisk, hun er i utgangspunktet gift, men med en fraværende ektemann, og hun har til alt overmål en elsker som kommer og går på farmen som han vil (”Stemme og antropologi” 21) 13

Moreover, as the Swedish scholar Claudia Lindén points out: “[a]tt läsa Blixen idag är att förvånad kastas in i ett universum av könsbyten, masker, instabila identiteter, konstruerade kön och diverse sexualiteter” (108).

14 Even though Lindén’s article primarily focuses on the short story “The Old Chevalier”, the parallels to Out of Africa are striking. The unstable gender identity and rejection of gender binaries that Selboe and Lindén describe in Blixen’s writing has connections to the rejection of the dichotomy between the physical body and the physical landscape. One rejection does not precede the other; rather, they interlock as a complex web of embodied identity negotiations.

The rejection of the essentialist link between sexuality and identity–that Blixen depicts–can be usefully compared to her portrayal of body and landscape. Prior to the corporeal turn within feminism, the field of gender studies was primarily categorized under post-structuralism, with the accompanying notion that language constructs reality.

15 Turning to the school of French feminism, in particular Hélène Cixous and

13 ”the head of the farm, but not a man, she is a white woman, but not British, she is initially married, but to an absent husband, and on top of all of this she has a lover who comes and goes on the farm as he pleases” (“Voice and Anthropology” 21)

14 ”Reading Blixen today entails being surprisingly thrown into a universe of sex changes, masks, unstable identities, gender constructions and various sexualities” (108)

15 For further reading on the corporeal turn within feminism, see for example Elizabeth Grosz ”Notes

Towards a Corporeal Feminism” (2010), which argues that: ”lived experiences are made possible and structured as such only through the social construction and inscription of biologies, physiologies or

28

her seminal work “The Laugh of Medusa” (1975), the focus on language becomes clear.

Cixous urges her reader to use writing to move beyond the entrapment of the own body. Cixous formulates this point in the following: “writing is precisely the very possibility of change , the space that can serve as a springboard for subversive thought, the precursory movement of a transformation of social and cultural structure” (879 emphasis in original). Later postmodern theorists, such as Judith Butler, turn against

Cixous and other French feminists who emphasize fundamental differences between the masculine and feminine, Butler critiques the reproduction of the conception of these differences ( Undoing Gender 207-208). Nevertheless, Butler’s main focus is the significance of language in the construction of gender and sex. She uses the idea of performativity to describe how this construction takes shape. Butler argues that sex is: ”a performatively enacted signification (and hence not ‘to’ be), one that released from its naturalized interiority and surface, can occasion the parodic proliferation and subversive play of gendered meanings” ( Gender Trouble 33). By moving away from: “naturalized notions of gender that support masculine hegemony and sexist power”, Butler means that these categories can be destabilized by questioning the “illusions of identity” (33-34). Nonmaterialists sometimes criticize material feminists in that material feminists draw the distinction between themselves and others on the basis that non-material feminism is entirely based on language.

16 In all fairness, Butler does state that: “There is always a dimension of bodily life that cannot be fully represented, even as it works as the condition and activating condition of language” ( Undoing Gender 198). Even so, the focus is on language and Butler states that she is not “a very good materialist” (198). As an example she describes how, when attempting to write about the body: “the writing ends up being about language” (198).

In contrast to these feminisms, trans-corporeality is tied to the material turn, new materialism and: “the idea that the dematerialization of the world needs to be reconsidered and research directed towards reconsideration of the mind-body dualism”

(Iovino and Oppermann 76). Even though gender studies and new materialism come from different theoretical perspectives, the identity negotiations in Out of Africa exemplify how the issues of gender in the text tie in with those of the landscape. anatomies” (15). Moreover, Grosz states that: “the body can be approached, not simply as an external object, but from the point of view of its being lived or experienced by the subject” (9).

16 See Sara Ahmed, “Imaginary Prohibitions: Some Preliminary Remarks on the Founding Gestures of the ‘New Materialism’”.

29

Moreover, as Myra J. Hird contends: “[f]ar from reinscribing traditional notions, new materialism … offers analyses that confound the often taken-for-granted immutability of sex and sexual difference found in some cultural theories” (231).

The blurring of the lines between identity and sexuality, which has often been observed in Blixen’s writing can be seen as related to the author’s depiction of bodily experiences of the landscape.

17 By rejecting the binary opposition between nature and culture, Karen Blixen opens up for the “epistemological time-space” or transcorporeality that Stacy Alaimo describes (“Trans-Corporeal Feminisms” 253). Out of

Africa places the traditional concept of nature at a crossroads where the boundaries between where the human ends and landscape begins are not defined. Beyond the separation of landscape and identity then, lies Blixen’s ecology of the self. Or as Blixen herself describes it: “a coffee-plantation is a thing that gets hold of you and does not let you go” (12).

17 See Dag Heede Det Umenneskelige: Analyser af seksualitet, køn og identitet hos Karen Blixen (2001) and Susan

Hardy Aiken Isak Dinesen and the Engendering of Narrative (1990).

30

4. Vivisecting an Ingrained Perception: Human and Nonhuman

Animal Relationships

We are rediscovering our interest in the space in which we are situated. Though we see it only from a limited perspective – our perspective – this space is nevertheless where we reside and we relate to it through our bodies.

(Maurice Merleau-Ponty The World of Perception )

In the previous chapter, the attribution of the concept of the trans-corporeal highlighted the intersection of the human and nonhuman in terms of landscape. Yet, new materialism is concerned with all matter. Therefore, the trans-corporeal transgression of boundaries is also applicable to human and nonhuman animals. For this particular reason it might seem strange that the chapter division of this thesis is based on which nonhuman elements I discuss. Surely, one could argue that this kind of division endorses a hierarchical structure, or at least separation, of different kinds of matter and life. However, this division is highly intentional and made in order to emphasize how similar the roles of landscape, nonhuman animals and humans are, which will be discussed in the final chapter of this thesis. By initially separating the two intersections into issues pertaining to landscape and issues pertaining to nonhuman animals respectively, the bringing together of them in the final chapter will show the similarity of the intersections and question their hierarchical separation within the

Western philosophical tradition.

In this chapter, the discussion on human and nonhuman animal relations in Out of Africa will be juxtaposed to Blixen’s essay on vivisection “Fra lægmand til lægmand”

(“From layman to layman”), in order to add a further understanding of the human and nonhuman animal relations. In doing so, the way the narrative portrayals of animals in

Out of Africa may be seen from another angle, which deals specifically with how Blixen perceives the ethical dimensions of nonhuman animals. Blixen uses her experience of life in Kenya to discuss the Danish domestic issue of animal testing. This will highlight the intersection of the political nonhuman animal controlled by the human and the wild nonhuman animal’s relation to the human.

31

When the Political and Wild Animal Meet

Blixen originally read her essay on vivisection on Danish radio on May 10 1954 before publishing it on May 11-12 in the newspaper Politiken ( Samlede Essays 336). The essay deals with the subject of animal testing on live animals, and Blixen expresses how she feels obliged to discuss this topic. As she begins, she states: “De kan, hvis De vil, lade være at lytte, men jeg kan ikke lade være at tale.” (279).

18 This indicates the responsibility Blixen feels to voice her ideas against vivisection. She states that it is possible that the listeners’ radios will be turned off, one after the other, but even if she is left talking only for herself she needs to finish (279). This need to speak on the topic of the rights of animals can be seen as a process of washing her hands of the practices of others. At least she will have said something for the beings that are silenced in society.

Moreover, the ill treatment of said nonhuman animals is also connected to a feeling of shame. This feeling of shame will be further elaborated on later in this chapter.

As she discusses the issue of vivisection and animal testing, she unravels an analysis of various power orders, which also include nonhuman animals. Naturally, there is a large difference between the life of the wild animals in Kenya and the conditions for the animals in Danish laboratories. However, the perception of the human in relation to the nonhuman appears to be applicable to both these cultural contexts. Moreover, this view also translates from the non-fiction into the fiction. In her