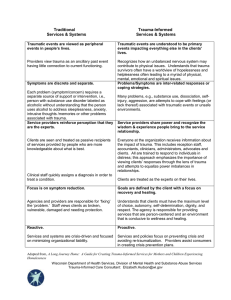

Complex Trauma and Disorders of Extreme

advertisement