Supporting graduate employability: HEI practice in other - i

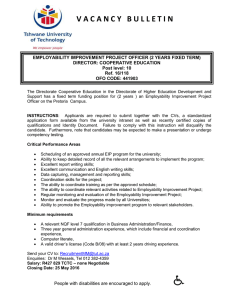

advertisement