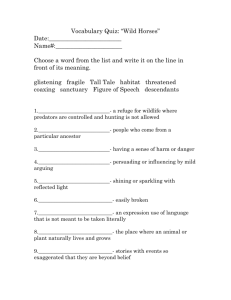

Marin Islands National Wildlife Refuge (NWR)

advertisement