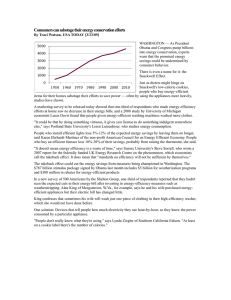

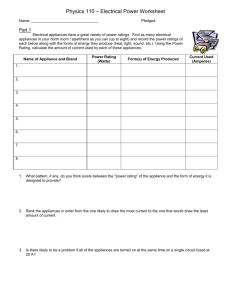

Energy efficiency policies for appliances

advertisement