Zero-Latency Tapping: Using Hover Information to Predict Touch

advertisement

Modeling and Prediction

UIST’14, October 5–8, 2014, Honolulu, HI, USA

Zero-Latency Tapping: Using Hover Information to Predict

Touch Locations and Eliminate Touchdown Latency

Haijun Xia1, Ricardo Jota1,2, Benjamin McCanny1,

Zhe Yu1, Clifton Forlines1,2, Karan Singh1, Daniel Wigdor1

1

2

University of Toronto

Tactual Labs

{haijunxia | jotacosta | bmccanny | zheyu | cforlines | karan | daniel}@dgp.toronto.edu

ABSTRACT

A method of reducing the perceived latency of touch input

by employing a model to predict touch events before the

finger reaches the touch surface is proposed. A corpus of 3D

finger movement data was collected, and used to develop a

model capable of three granularities at different phases of

movement: initial direction, final touch location, time of

touchdown. The model is validated for target distances >=

25.5cm, and demonstrated to have a mean accuracy of

1.05cm 128ms before the user touches the screen. A user

study of different levels of latency reveals a strong

preference for unperceivable latency touchdown feedback. A

form of ‘soft’ feedback is proposed, as well as other

performance-enhancing uses for this prediction model.

Figure 1: The model predicts the location and time of a touch.

Parameters of the model are tuned to the latency of the device

to maximize accuracy while guaranteeing performance.

INTRODUCTION

The time delay between user input and corresponding

graphical feedback, here classified as interaction latency,

has long been studied in computer science. Early latency

research indicated that the visual “response to input should

be immediate and perceived as part of the mechanical

action induced by the operator. Time delay: No more than

0.1 second (100ms)” [25]. More recent work has found that

this threshold is, in fact, too high, as humans are able to

perceive even lower levels of latency - for direct touch

systems, it has been measured as low as 24ms when tapping

the screen [20], and 6ms when dragging [27]. Furthermore,

input latencies well below 100ms have been shown to

impair a user’s ability to perform basic tasks [20, 27].

replaced a general-purpose processor and software, they

employ a high-speed projector rather than a display panel,

and each is capable of displaying only simple geometry.

While the touchdown latency of current commercial touch

devices can be as low as 75ms, this latency is still

perceptible to users. Eliminating latency, or at least

reducing it beyond the limits of human perception and

performance impairment, is highly desirable. Both Leigh et

al. and Ng et al. demonstrated direct-touch systems capable

of less than 1ms of latency [22, 27]. While compelling, these

are not commercially viable for most applications: an FPGA

This paper investigates methods for eliminating the

apparent latency of tapping actions on a large touchscreen

through the development and use of a model of finger

movement. We track the path of a user’s finger as it

approaches the display and predict the location and time of

its landing. We then signal the application of the impending

touch so that it can pre-buffer its response to the touchdown

event. In our demonstration system, we trigger a visual

response to the touch at the predicted point before the finger

lands on the screen. The timing of the trigger is tuned to the

system’s processing and display latency, so the feedback is

shown to the user at the moment they touch the display. The

result is an improvement in the apparent latency as touch

and feedback occur simultaneously.

While completely eliminating latency from traditional form

factors may ultimately prove to be impossible, we believe

that it is possible to reduce the apparent latency of an

interactive system. We define apparent latency as the time

between an input and the system’s soft feedback to that

input, which serves only to show a quick response to the

user (e.g.: pointer movement, UI buttons being depressed),

as distinct from the time required to show the hard feedback

of an application actually responding to that same input.

Permission to make digital or hard copies of all or part of this work for personal

or classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or

distributed for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice

and the full citation on the first page. Copyrights for components of this work

owned by others than the author(s) must be honored. Abstracting with credit is

permitted. To copy otherwise, or republish, to post on servers or to redistribute to

lists, requires prior specific permission and/or a fee. Request permissions from

Permissions@acm.org.

UIST '14, October 05 - 08 2014, Honolulu, HI, USA

Copyright is held by the owner/author(s). Publication rights licensed to ACM.

ACM 978-1-4503-3069-5/14/10…$15.00.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2642918.2647348

In order to predict the user’s landing point, we must first

understand the 3D spatial dynamics of how users perform

touch actions. To this end, we augmented a Samsung

SUR40 tabletop with a high fidelity 3D tracking system to

205

Modeling and Prediction

UIST’14, October 5–8, 2014, Honolulu, HI, USA

record the paths of user finger movements through space as

they performed basic touchscreen tasks. We collected data

on input paths by asking 15 participants to perform repeated

tapping tasks. We then analyzed this data using various

numerical and qualitative observations to develop a

prediction model of 3D finger motion for touch-table device

interaction. This model, which was validated by a

subsequent study for targets at least 25.5cm distant, enables

us to predict the movement direction, touch location, and

touch time prior to finger-device contact. Using our model,

we can achieve a touch-point prediction accuracy of 1.05cm

on average 128ms before the user touches the display. This

accuracy and prediction time horizon is sufficient to reduce

the time between the finger touch down and the system’s

apparent response to beneath the 24ms lower bound of

human perception, described by Jota et al [20].

Most touch sensors employed today are based on projective

capacitance. Fundamentally, the technique is capable of

sensing the user’s presence centimeters away from the

digitizer, as is done with the Theremin [31]. Such sensors

employed today are augmented with a ground plane,

purposefully added to eliminate their ability to detect a

user’s finger prior to touch [6]. More recently, sensors have

been further augmented to include the ability to not only

detect the user’s finger above the device, but also to detect

its distance from the digitizer [2, 14, 18, 34].

In this paper, we first describe relevant prior art in the areas of

hover sensing, input latency, and touch prediction. We then

describe a pair of studies that we used to formulate and then

validate our predictive model. Next, we describe a third study

in which participants’ preferences for low-latency touch input

were investigated. Finally, we describe a number of uses for

our model beyond simple feedback and outline future work

that continues the exploration of touch prediction.

Hover has long been the domain of pen-operated devices [9,

19]. Subramanian et al. suggest that the 3D position of a

pointing device affects the interaction on the surface [30].

The authors propose a multi-layer application, with an active

usage of the space above the display, where users

purposefully distance the pen from the display to activate

actions. Grossman et al. present a technique that utilizes the

hover state of pen-based systems to navigate through a

hover-only command layer [15]. Spindler et al. [28] propose

that the space above the surface be divided into stacked

layers, with layer specific interactions – this is echoed by

Grossman et al. [16], who divided the space around a

volumetric display into two spherical ‘layers’ with subtly

differentiated interaction. This is distinct from Wigdor et al.,

who argued for the use of the hover area as a ‘preview’

space for touch gestures [33], similar to Yang et al. who

used hover sensing to zoom on-screen targets [37]. In

contrast, Marquadt et al. recommend that the space above

the touch surface and the touch surface be considered one

continuous space, and not separate interaction spaces [24].

Use of Hover

Prior work has explored the use of sensing hover to enable

intentional user input. Our work, in contrast, effectively

hides the system’s ability to detect hover from the user,

using it only for prediction of touch location and timing,

and elimination of apparent latency.

RELATED WORK

We draw from several areas of related work in our present

research: the detection and use of hovering information in HCI,

the psychophysics of latency, the use of predictive models in

HCI, and the modeling of human motion in three dimensions.

Hover Sensing

A number of sensing techniques have been employed to

detect the position of the user prior to touching a display. In

HCI research, hover sensing is often simulated using optical

tracking tools such as the Vicon motion capture system, as

we have done in this work. The user is required to wear or

hold objects augmented with markers, as well as the need to

deploy stationary cameras. A more practical approach for

commercial products, markerless hover sensing has been

demonstrated using optical techniques, including through

the use of an array of time-of-flight based range finders [3]

as well as stereo and optical cameras [35].

These projects focused on differentiating the space around

the display, and using it as an explicit interaction volume.

Our approach is more similar to that taken by Hachisu and

Kajimoto [17], who demonstrate the use of a pair of photosensing layers to measure finger velocity and predict the

time of contact with the touch surface. We build on this

work through the addition of a model of motion that allows

the prediction of not only time, but also early indication of

direction, as well as later prediction of the location of the

user’s touch, enabling low-latency visual feedback in

addition to the audio feedback they provide.

Non-optical tracking has also been demonstrated using a

number of technologies. One example is the use of

acoustic-based sensors, such as the “Flock of Birds”

tracking employed by Fitzmaurice et al. [8], which enables

six degrees of freedom (DOF) position and orientation

sensing of physical handheld objects. Although popular in

research applications, widespread application of this sensor

has been elusive. More common are 5-DOF tools using

electro-magnetic resonance (EMR). EMR is commonly

used to track the position and orientation of styli in relation

to a digitizer, and employed in creating pen-based user

input. Although typically limited to a small range beyond

the digitizer in commercial applications, tracking with EMR

has been used in much larger volumes [12].

Latency

Ng et al. studied the user perception of latency for touch

input. For dragging actions with a direct touch device, users

were able to detect latency levels as low as 6ms [27]. Jota et

al. studied the user performance of latency for touch input

and found that dragging task performance is affected if

latency levels are above 25ms [20]. In the present work, we

focus on eliminating latency of the touchdown moment

206

Modeling and Prediction

UIST’14, October 5–8, 2014, Honolulu, HI, USA

when the user first touches the screen. Jota et al. found that

users are unable to perceive latency of responses to tapping

that occur in less than 24ms [20] – we use prediction of

touch location to provide soft touchdown feedback within

this critical time, effectively eliminating perceptible latency.

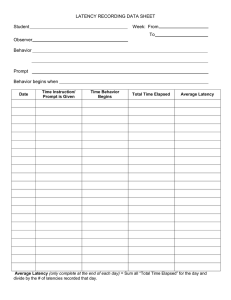

DATA COLLECTION

To form our predictive model of tap time and location, we

began by collecting data of tap actions on a touchscreen

display. Participants performed tap gestures with varying

target distance and direction of gesture. The data were then

used to build our model, which we subsequently validated

with a study we will later describe.

Predicting Input

Predicting users’ actions has been an active area of research

in the field of HCI. Mackenzie proposes the application of

Fitts's Law to predict movement time for standard touch

interfaces [23]. By building a Fitts's model for a particular

device, the movement time can be predicted given a known

target and cursor position. Wobbrock et al. complements

this approach with a model to predict pointing accuracy

[36]. Instead of predicting movement time, a given

movement time is used to predict error. In many pointing

experiments, the input device is manipulated by in-air

gestures, including Fitts’s original stylus-based apparatus

[7]. Murata proposes a method for predicting the intended

target based on the current mouse cursor trajectory [26].

The author reports movement time reductions when using

the predictive algorithm, but notes limited returns for dense

target regions. Baudisch et al. adopted this approach:

instead of jumping the cursor close to the target, this

technique wraps eligible targets around the cursor [4].

Participants

We recruited 15 right-handed participants (6 female)

aged 22-30 from the local community. Participants

reported owning 2 (mean) touch devices and spend 2-4

hours a day using them. Participants were paid $20 for a

half-hour session.

Apparatus

The study was implemented using two different sensors: to

sense touch, a Microsoft Surface table 2.0 was used

(Samsung SUR40 with PixelSense). Pre-touch data was

captured using a Vicon tracking system. Participants wore a

motion capture marker-instrumented ring on their index

fingertip, which was tracked in 3D at 120Hz.

The flow of the experiment was controlled by a separate

PC, which received sensing information from both the

Surface touch system and the Vicon tracking system, while

triggering visual feedback on the Surface display. The

experiment was implemented in python and shown to the

user on the Surface table. It was designed to (1) present

instructions and apparatus to the participant, (2) record the

position and rotation of the tracked finger, (3) receive

current touch events from the Surface, (4) issue commands

to the display, and (5) log all of the data.

We sought to build on these projects by developing a model

of hand motion while performing touch-input tapping tasks,

and apply this model to reducing apparent latency.

Models of Hand Motion

Biomechanists [32] and neuroscientists [10, 13] are actively

engaged in the capture and analysis of 3D human hand

motion. Their interest lies primarily in the understanding of

various kinematic features, such as muscle actuation and

joint torques, as well as cognitive planning during the hand

movement. Flash [10] modeled the unconstrained point-topoint arm movement by defining an objective function and

running an optimization algorithm. They found that the

minimization of hand jerk movements generates an

acceptable trajectory. Following the same approach, Uno

[32] optimizes for another kinematic feature, torque, to

generate the hand trajectory. While informative, these

models are unsuitable to our goal of reducing latency, as

they are computationally intensive and cannot be computed

in real-time (for our purposes, as in little as 30ms).

Task

Participants performed a series of target selection tasks,

modeled after traditional pointing experiments, with some

modifications made to ensure they knew their target before

beginning the gesture, thus avoiding contamination of

collected data with corrective movements. Target location

was randomized, rather than performed in sequentialcircle. Further, to begin each trial, participants were

required to touch and hold a visible starting point

(r=2.3cm), immediately after the target location was

shown. They were required to hold the starting point until

an audio cue was played (randomly between 0.7 and 1.0

seconds after touch). If the participant anticipated the

beginning of the trial and moved their finger early, the trial

would be marked as an error.

We propose a generic model focusing on the prediction of

landing location and touch time based on the pre-touch

movement to reduce the time between the finger landing on

the screen and the system’s apparent response.

Immediately after the participants touched the starting point,

at the opposite side of the circular arrangement a target point

would appear for participants to tap. The target size of

2.3cm was selected as a trade-off between our need to

specify end-position while minimizing corrective

movements. Once a successful trial was completed,

participants were instructed to return to another starting

point for the next trial. Erroneous tasks were indicated with

feedback on the Surface display and repeated.

Having examined this related work, we turned our attention

to the development of our predictive model of hand motion

when performing pointing tasks on a touchscreen display.

To that end, we first performed a data collection

experiment. The data from this experiment was then used to

develop our model.

207

Modeling and Prediction

UIST’14, October 5–8, 2014, Honolulu, HI, USA

Procedure

ANALYSIS & PREDICTING TOUCH

Participants were asked to complete a consent form and a

questionnaire to collect demographic information. They

then received instruction on how to interact with the

apparatus and successfully completed 30 training trials.

After the execution of each trial, a text block at the top right

corner of the screen would update the cumulative error rate

(shown as %). Participants were instructed to slow down if

the error rate was above 5%, but were not given any

instructions regarding their pre-touch movement.

Having collected these tapping gestures, we turned our

attention to modeling the trajectories with the primary goal

of predicting the time and location of the final finger touch.

Here we describe our approach, beginning with a discussion

of the attributes of the touch trajectories, followed by the

model we derived to describe them.

Note that our three-dimensional coordinate system is righthanded: x and y representing the Surface screen; the origin

at the bottom-left corner of the Surface display; and z, the

normal to the display.

Design

Tasks were designed according to two independent

variables: target direction (8 cardinal directions) and target

distance (20.8cm and 30.1cm). The combination of these

two variables produces 16 unique gestures. There were four

repetitions for each combination of direction and distance.

Therefore, a session included a total of 64 actions. The

ordering of the trials was randomized within each session.

Participants completed 3 sessions and were given a 5minute break between sessions.

Numerical and Qualitative Observations

Time & Goals: participants completed each trial with an

mean movement time of 416ms (std.: 121ms). Our system

had an average end-to-end latency of 80ms: 70ms from the

Vicon system, 8ms from the display, and 2ms of

processing. Thus, to drop touch-down latency below the

24ms threshold, our goal was to remove at least ~56ms via

prediction. Applying our work to other systems will require

additional tuning.

In summary, 15 participants performed 192 trials each, for a

total of 2880 trials.

Movement phases: Figure 3 shows that all the trajectories

have one peak, with a constant climb before, and a constant

decline after. However, we did not find the peak to be at the

same place in-between trajectories. Instead the majority of

trajectories are asymmetrical, 2.2% have a peak before 30%

of the total path, 47.9% have a peak between 30-50% of the

total path, 47.1% have a peak between 50-70% of the total

path, and 2.8% have a peak after 80% of the trajectory

completed path.

Measures and Analysis Methodology

For each successful trial we captured the total completion

time; finger position, rotation, and timestamp for every

point in the finger trajectory; as well as the time participants

touched the screen. Tracking data was analyzed for

significant tracking errors, with less than 0.3% of the trials

removed due to excessive noise in tracking data. Based on

the frequency of the tracking system (120Hz) and the speed

of the gestures, any tracking event that was more than

3.5cm away from its previous neighbor was considered an

outlier and filtered (0.6%). The raw data (including outliers)

for a particular target location are shown in Figure 2.

We have found it useful to divide the movement into three

phases: lift-off, which is characterized by a positive change in

height, continuation, which begins as the user’s finger starts to

dip vertically, and drop-down, the final plunge towards the

screen. Each of the lift-off and drop-down phases has interesting

characteristics, which we will examine.

After removing 8 trials due to tracking noise, we had 2872

trials available for the development of our predictive model.

Figure 2: Overlay of all the pre-touch approaches to a

northwest target. The blue rectangle represents the

interactive surface used in the study.

Figure 3: Side view overlay of all trials, normalized to start

and end positions.

208

Modeling and Prediction

UIST’14, October 5–8, 2014, Honolulu, HI, USA

Figure 4: Trajectory for the eight directions of movement,

normalized to start at the same location (center). The blue lines

represent the straight-line approach to each target.

Figure 6: Trajectory prediction for line, parabola, circle and

vertical fits. Future points of the actual trajectory (black dots)

fit a parabola best.

Lift-off direction: As might be expected, the direction of

movement of the user’s hand above the plane of the

screen is roughly co-linear to the target direction, as

shown in Figure 4. Fitting a straight line to this

movement, the angle of that line to a straight line from

starting point to the target is, on average, 4.78°, with a

standard deviation of 4.51°. Depending on the desired

degree of certainty, this information alone is sufficient to

eliminate several potential touch targets.

Predictive Touch Model

Drop-down direction: Figure 5 and Figure 7 show the

trajectory of final approach towards the screen. As can be

seen, the direction of movement in the drop-down phase

roughly fits a vertical drop to the screen. We also note that,

as can be seen in Figure 7, the final approach when viewed

from the side is roughly parabolic. It is clear when

examining Figure 7 that a curve, constrained to intersect on

a normal to the plane, will provide a rough fit. We

examined several options, shown in Figure 6, and found

that a parabola, constrained to intersect the screen at a

normal, and fit to the hover path, would provide the best fit.

Prediction 1: Direction of Movement

Lift-off begins with a user lifting a finger off the touch

surface and ends at the highest point of the trajectory

(peak). As we discussed, above, this often ends before the

user has reached the halfway point towards their desired

target. As is also described, the direction of movement

along the plane of the screen can be used to coarsely

predict a line along which their intended target is likely to

fall. At this early stage, our model provides this line,

allowing elimination of targets outside of its bounds.

Figure 5: Final finger approach, as seen from the approaching

direction

Figure 7: Final finger approach, as seem from the side of the

approaching direction

Based on these observations, we present a prediction

model, which makes three different predictions at three

different stages in the user’s gesture. They are initial

direction, final touch location, and final touch time.

Making predictions at three different moments allows our

model to provide progressively more accurate information,

allowing the UI to react as early as possible.

209

Modeling and Prediction

UIST’14, October 5–8, 2014, Honolulu, HI, USA

The timing of this phase is tuned based on the overall

latency of the system, including that of the hover sensor:

the later the prediction is made, the more accurate it will be,

but the less time will be available for the system to respond.

The goal is to tune the system so that the prediction arrives

at the application so that it can respond immediately, and

have its response shown on the screen at the precise

moment the user touches. Through iterative testing, we

found that, for the latency of our system (display + Vicon,

approximately 80ms) setting thresholds of 4cm (distance to

display) and 23o (angle to plane) yielded the best results.

Given these unusually high latencies values, a more typical

system would see even better results.

With these thresholds, our model predicts a touchdown

location with an average error (distance to actual touch point)

of 1.18cm and standard deviation of 1.09cm, on average, 91

milliseconds (std.: 72ms) before touchdown and at an

average distance of 3.22cm (std.: 1.30cm) above the display.

For the same set of trials, the errors for other curves (see

Figure 6): circular fit (avg.: 1.72cm, std.: 1.62cm), vertical

drop (avg.: 2.43cm, std.: 2.04cm) and a linear fit (avg.:

9.3cm, std.: 4.83cm) are larger than the parabolic fit.

The visual results and statistics indicate that pre-touch data

has the potential to predict touch location long before the

user touches the display. We validate the parabolic

prediction model in a secondary study by using it to predict

touch location in real time.

Figure 8: The parabola is fitted in the drop-down plane with

(1) an initial point, (2) the angle of movement, (3) and the

intersection is orthogonal with the display

Prediction 2: Final Touch Location

A prediction of the final location of the touch, represented

as an x/y point, is computed by fitting a parabola to the

approach trajectory. This parabola (Figure 8) is constrained

as follows: (1) the plane is fit to the (nearly planar) dropdown trajectory of the touch; (2) the position of the finger

at the time of the fit is on the parabola; (3) the angle of

movement at the time of the fit is made a tangent to the

parabola; (4) the angle of intersection with the display is

orthogonal. Once the parabola is fit to the data, and

constrained by these parameters, its intersection with the

display comprises the predicted touch point. The fit is made

when the drop-down phase begins. This is characterized by

two conditions: (1) the finger’s proximity to the screen; and

(2) the angle to xy plane is higher than a threshold.

Prediction 3: Final Touch Time

Given that the timing of the prediction of final touch

location is tuned to the latency of the system on which it is

running, the time that it is delivered ahead of the actual

touch is reliable. The goal of this final step is to provide a

highly-accurate prediction of the time the user will touch,

which necessitates waiting until the final approach to the

display. We observed that the final ‘drop’ action, beyond

the final 1.8cm of a touch gesture, experiences almost no

deceleration. Thus, when the finger reaches 1.8cm from the

display, a simple linear extrapolation is applied assuming a

constant velocity.

We are able to predict within 2.0ms (mean; std.: 19.5ms),

51ms (mean; std.: 42ms) before touchdown. Note that, due

to the 80ms latency of our Vicon sensor, this prediction is

typically generated after the user has actually touched. We

include it here for use with systems not based on computer

vision and subject to network latency.

For each new point i, when the conditions are satisfied, the

tapping location is predicted. To calculate the tapping

location, we first fit a vertical plane to the trajectory.

Given the angle d and (𝑥! , 𝑧! ), we predict the landing

point, (𝑥! , 𝑧! ), by fitting a parabola:

𝑥 = 𝑎𝑧 ! + 𝑏𝑧 + 𝑐

Based on the derivatives at (𝑥! , 𝑧! ) and (𝑥! , 𝑧! ):

𝑥!! = !!

!"#(!)

𝑥!! = 0

we calculate a, b, and c as follows:

𝑎 = 𝑥!! − 𝑥!!

2 𝑧! – 𝑧!

MODEL EVALUATION

𝑏 = 𝑥!! − 2𝑎𝑧! Having developed our model using the collected data, we

sought to validate the model outside the condition of the

first study. We recruited 15 new right-handed participants

from the local community (7 female) that had not

participated in the first study with ages ranging from 20 to

30. On average, our participants own two touch devices

and spend two to four hours a day using them.

Participants were paid $10 for a half-hour session.

𝑐 = 𝑥! – 𝑎𝑧!! – 𝑏𝑧!

The landing point in this plane is defined as:

𝑥! , 𝑧! = (𝑐, 0)

Converting 𝑥! , 𝑧! back to the original 3D Vicon tracking

coordinate system yields the landing position.

210

Modeling and Prediction

UIST’14, October 5–8, 2014, Honolulu, HI, USA

From the first study we observed that arm joint movement

skews the trajectory. The longer the distance, the more

skewed the trajectory becomes. Secondly, people

dynamically correct the trajectory. The smaller the target,

the more corrections were observed. To further study these

effects, we included target distance and size as independent

variables. Therefore, our validation study was designed

according to three different independent variables: target

direction (8 cardinal directions), target distance (25.5cm,

32.4cm, and 39.4cm), and target size (1.6cm, 2.1cm, and

2.6cm). The combination of these three variables produces

72 unique tasks. The order of target size and distance was

randomized, with target direction always starting with the

south position, and going clockwise for each combination

of target size and distance. Participants completed 3

sessions and were given a break after each session.

no understanding if unperceivable latency UI is, indeed,

preferred by users. Using our predictive model, we

generated widgets with different levels of latency and

evaluated what amount of latency participants prefer. We

were particularly curious about participants’ responses to

negative latency – that is, having a UI element respond

before they finish reaching for it.

Participants

We recruited 16 right-handed participants from the local

community (8 male, 8 female) with ages ranging from 20 to

31. On average, our participants own two touch devices and

spend three to four hours a day using them. We paid

participants $10 for a half-hour session.

Task

The participants were shown a screen with two buttons,

each with different response latency. Before tapping

each button once, they were asked to touch and hold a

visible starting point until audio feedback, which would

occur randomly between 0.7 and 1.0 seconds later, was

given. They then were asked to indicate which button

they preferred.

The procedure and apparatus were identical to the first

study, with the exception of the prediction model running in

the background in real time. The prediction model did not

provide any feedback to the participants. For each trial we

captured the trajectories and logged the prediction results.

Results

Design

Prediction 1: On average, the final touch point was within

4.25° of the straight-line prediction provided by our model

(std.: 4.61°). On average, this was made available 186ms

(mean; std.: 77ms) before the user touched the display. We

found no significant effect for target size, direction, or

distance on prediction accuracy.

Tasks were designed with one independent variable,

response latency. To limit combinatorial explosion, we

decided to provide widget feedback under five different

conditions: immediately as a finger prediction is made (0ms

after prediction) and then artificially added latencies of 40,

80, 120, and 160ms to the predicted time, resulting in 10

unique pairs of latency. To remove the possible preference

for buttons placed to the left or right, we also flipped the

order of the buttons, resulting in 20 total pairs. The ordering

of the 20 pairs was randomized within each session.

Latency level was also randomly generated. Participants

completed 7 sessions of 20 pairs and were given a 1-minute

break between sessions, for a total of 2240 total trials.

Prediction 2: On average, our model predicted a touch

location with an accuracy of 1.05cm (std.: 0.81cm). The

finger was, on average, 2.87cm (std.: 1.37cm) away from

the display when the prediction was made. The model is

able to predict, on average, 128ms (std.: 63ms) before

touching the display, allowing us to significantly reduce

latency. We found no significant effect for target size,

direction, or distance on prediction accuracy.

Methodology

To calculate the effective latency we first calculate the

response time and the touch time. The response time is

calculated by artificially adding to the time of prediction

some latency (between 0 and 160ms). For touch time, we

consider when the Surface detected the touch and subtract a

known Surface latency of 137ms, measured using the

methodology described in [27]. The effective latency is the

difference between the response time and the touch time.

Prediction 3: On average, our model predicted the time of

the touch within 1.6ms (std.: 20.7ms). This prediction was

made, on average, 49ms before the touch was made (std.:

38ms). We found no significant effect for target size,

direction, or distance on prediction accuracy.

These results indicate that our prediction model can be

generalized to different target distances, sizes, and

directions, with an average drift from the touchdown

location of 1.05cm, 128ms prior to the finger touching the

device. To provide context, given that our mean trial

completion time for the experiment was approximately

447ms, this means that we were able to predict the

location of the final touch before 29% of the approach

action was completed.

Results

After pressing both buttons in one trial, participants

indicated which button they preferred. Each trial resulted in

2 points (not shown) in Figure 9; one at (L1, 1) for the

preferred latency L1, and one at (L2, 0) for the other

latency L2. For each participant, a curve is fit to 280 data

points. Three possible curves emerged, increasing,

decreasing, and peaked. During debriefing, we questioned

participants regarding how they select the preferred latency,

and identified three strategies (Faster is Always Better, On

Touch, Visible Latency), aligned with the curve of each

participant. Three corresponding curves in Figure 9 were

PREFERRED LATENCY LEVEL

Armed with our prediction model, we are able to provide

tapping feedback with a latency range from -100ms to

100ms. From previous work, we know that latencies below

24ms are unperceivable by humans [20], however we have

211

Modeling and Prediction

UIST’14, October 5–8, 2014, Honolulu, HI, USA

NEW OPPORTUNITIES AND CONSIDERATIONS

In this section, we detail a number of new interaction

opportunities that our prediction model provides and

discuss some of the considerations that system designers

must address when employing these techniques.

Reducing Apparent Latency

Our motivating use case is the reduction of visual latency in

order to provide the user with a more reactive touch-input

experience. Based on our validation study, our model can

predict touch location accurately enough at a sufficient time

horizon to support simultaneous touch and visual response.

A prediction 128ms prior to the finger touching the device

is sufficient to pre-buffer and display the visual response to

the input action. We believe that this work validates the

assertion that computer systems can be made to provide

immediate, real-world-like responses to touch input.

Figure 9: Preference curve for each observed trend and

average latency preference for all participants.

Beyond accelerating traditional visual feedback, our

approach enables a new model of feedback based on

predicted and actual input. With the prediction data from

this model, soft feedback can be designed to provide an

immediate response to tapping, eliminating the perception

of latency. After the touch sensor captures the touch event,

a transition from the previous soft feedback to the next

user interface (UI) state can be designed to provide a

responsive and fluent experience, instead of showing the

corresponding UI state directly.

generated from the participants in each of these three

groups. The dotted line is a curve fit to all data points,

indicating that overall participants preferred latencies

around 40ms.

Faster is Always Better. Four participants that preferred

negative latency were aware that the system was providing

feedback before the actual touch, but are confident that the

prediction is always accurate and therefore, the system

should respond as soon as a prediction is possible.

Reducing Programmatic Latency

On Touch. Eight participants preferred a system where

effective latency is between 0ms and 40ms. Participants

commented that they liked that the system reacted exactly

when their finger touched, but not before. When asked why

they did not prefer negative latency, participants mentioned

loss of control and lack of trust regarding the predictive

accuracy of the system as reasons for this preference.

Beyond changes to the visual appearance of GUI elements,

touch-controlled applications execute arbitrary application

logic in response to input. A 128-200ms prediction horizon

provides system designers with the intriguing possibility of

kicking-off time consuming programmatic responses to

input before the input occurs.

As an example, consider the widely adopted practice of precaching web content based on the hyperlinks present in the

page being currently viewed. Pre-caching has been shown

to significantly reduce page-loading times. However, it

comes at the expense of increasing both bandwidth usage

and the loads on the web servers themselves, as content is

often cached but not always consumed. Additionally, with

the potential for many referenced URLs on any one page, it

is not always clear to algorithm designers which links to

pre-fetch, meaning that clicked-on links may not have

already been cached.

Visible Latency. Four participants preferred visible latency.

When asked about the feeling of immediate response, they

expressed that they were not yet confident regarding the

predictive model and felt that an immediate response wasn’t

indicative of a successful recognition. Visible latency gave

them a feeling of being in control of the system and,

therefore, they preferred it to immediate response. This was

true even for trials where prediction was employed.

Our results show that there is a strong preference for

latencies that are only achievable through the use of

prediction. Overall, our participants indicated that they

preferred the lower-latency button in 62% of the study’s

trials. We ran a Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test comparing the

percent of trials where the lower latency was preferred to

the percent of trials where the higher latency was

preferred, and found a significant difference between the

two percentages (Z = 2.78 p = 0.003). 12 out of 16

participants preferred effective latencies below 40ms,

which was concluded to be unperceivable for 85% of the

participants [20].

Figure 10: Transitions between 3 states of touch

input that model the starting and stopping of actions, based on

prediction input.

212

Modeling and Prediction

UIST’14, October 5–8, 2014, Honolulu, HI, USA

A web-browser coupled with our input prediction model

would gain a 128-200ms head-start on loading linked

pages. Recent analysis has suggested that the median webpage loading time for desktop systems is 2.45s [1]. As such,

a head-start could represent a 5-8% improvement in page

loading time, without increasing bandwidth usage or server

burden. Similar examples include the loading of launched

applications and the caching of the contents of a directory.

The model relies on a high fidelity 3D tracking system,

currently unavailable for most commercial products. Here

we provide a detailed discussion about how to enable it in

everyday life. We used a Vicon tracking system, running at

120Hz, to capture the pre-touch data. As this high

frequency tracking is not realistic for most commercial

products, we tested the model at 60Hz, slower than most

commercial sensors. Although prediction is delayed 8ms on

average, the later fit has the benefit of increasing prediction

accuracy, because the finger is closer to the display.

To fully take advantage of predicted input, we propose a

modification to the traditional 3-state model of graphical

input, proposed by Buxton [5], that allows for

programmatic responses to be started and aborted as

appropriate as the input system updates its understanding of

the user’s intent. Figure 10 shows this model: in State 1,

related actions can be issued by the input system as

predictions (direction, location, and time) of a possible

action are received. When no actual input is being

performed (e.g. the user retracts hand), the input system

will stop all actions. When the actual touch target turns out

not to be the predicted one, the system may also stop all

actions but this will not add extra latency compared to the

traditional 3-state model. On the other hand, if the touch

sensor confirms the predicted action, the latency of the

touch sensor, network, rendering, and all the procedure

related parts will be reduced.

Some commercial products already include accurate hover

sensing technique, such as Wacom Intuos with EMR-based

sensor and Leap Motion with vision-based sensor; both are

able to run at 200Hz, with sub-millimeter accuracy.

Moreover, the model predicts tapping location when the

finger is 2.87cm and 3.22cm away from the screen in our

studies; these results are within capabilities of EMR [12] and

vision. Additionally, a number of plausible technologies for

achieving hover sensing appeared recently in HCI research.

HACHIStack [17] has a sensing height of 1.05cm above a

screen with 31µs latency. Retrodepth [21] can track hand

motion in a large 3D physical input space of 30x30x30cm.

Therefore, we believe an accurate, low-latency hover sensing

is on its way soon. We also envision that, when faster touch

sensor and CPU finally bring the nearly zero tapping latency,

this model will remain useful for achieving negative latency,

impossible even for a zero-latency touch sensor.

Recognizing unintended input

Another possible application of our prediction model is the

reduction of accidental input by masking unintended areas.

Based on our data analysis, the lift-off itself affords a

coarse prediction of target direction, as the majority of

touches we recorded were roughly planar. In addition, as

the prediction target is updated, the potential area for

touchdown will shrink. Therefore, the input system can

label the touch events in the areas where touchdown is not

likely as accidental events and ignore them.

In this paper, we built a prediction model and evaluate long

ballistic pointing tasks. However, in realistic tasks, the

finger motion will be much more complex, with pauses,

hesitation, and short tracking distances. To make the model

robust to these changes, we propose the fine-tuning of two

variables that determine when the system starts predicting:

the vertical distance, tuned at 4cm (in Z) to avoid direction

changes normal to touch approaches, and approach angle

tuned at 23° (for our system) to confirm that the finger

entered a drop down phase. With this tuning, the model

predicts location and time in the last 29% of the entire

trajectory. Other kinematic features, such as the

approaching velocity and direction can also be integrated

into the model to make it more robust. Still, there is no

doubt that the model would benefit from evaluation with

real tasks, and we encourage the effort to make the model

work perfectly in the real world.

DISCUSSION

Our results indicate that solving the problem of latency has

clear implications about how users perceive system

performance. If the predicted touchdown point is not

accurate users can detect the difference, not always

favorably, especially when presented with negative

latency. On the other hand, it seems that if we are capable

of eliminating perceived latency, with time, users will

adapt and expect an immediate response out of their

interactive systems.

CONCLUSION

Our prediction model is not constrained to only solving

latency. The approach is rich in motion data and can be

used to enrich many UIs. For example, the velocity of a

finger can be mapped to pressure, or the approach direction

can be mapped to different gestures. Equally important,

perhaps, is the possibility to predict when a finger is leaving

a display but not landing again inside the interaction

surface, effectively indicating that the user is stopping

interaction. This can be useful, for example, to remove UI

elements from a video application when the user is leaving

the interaction region.

We present a prediction model for direction, location, and

contact time of a tapping action on touch devices. With this

model, the feedback is shown to the user at the moment

they touch the display, eliminating the touchdown latency.

Results from the user study reveal a strong preference for

unperceived latency feedback. Also, predicting the touch

input long before the actual touch brings the opportunity to

reduce not only the visual latency but also latency of

various parts of a system that are involved in the response

to the predicted touch input.

213

Modeling and Prediction

UIST’14, October 5–8, 2014, Honolulu, HI, USA

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

19. Hinckley, K. et al.1998. Interaction and modeling

techniques for desktop two-handed input. UIST '98, 49-58.

20. Jota R. et al. 2013. How fast is fast enough? A study of the

effects of latency in direct-touch pointing tasks. CHI '13.

21. Kim D. et al. 2014. RetroDepth: 3D silhouette sensing for

high-precision input on and above physical surfaces. CHI

'13, 1377-1386.

22. Leigh, D. et al. 2014. High-rate, low-Latency multi-touch

sensing with simultaneous orthogonal multiplexing. UIST

‘14

23. MacKenzie, I. S.. 1995. Movement time prediction in

human-computer interfaces. Readings in HCI, 483-493.

24. Marquardt N. et al. 2011. The continuous interaction space:

interaction techniques unifying touch and gesture on and

above a digital surface. INTERACT '11, 461-476.

25. Miller, R. B.. 1968. Response time in man-computer

conversational transactions. Joint Comp. 1968, 267-277.

26. Murata, A.. 1998. Improvement of pointing time by

predicting targets in pointing with a PC mouse. IJHCI '98.

10, 1, 23–32.

27. Ng, A., Lepinski, J., Wigdor, D., Sanders, S., and Dietz, P..

2012. Designing for Low-Latency Direct-Touch Input.

UIST '12, 453-464.

28. Spindler, M., Martsch, M., and Dachselt, R.. 2012 Going

Beyond the Surface: Studying Multi-Layer Interaction

Above the Tabletop. CHI '12, 1277-1286.

29. Steed, A. 2008. A simple method for estimating the latency

of interactive, real-time graphics simulations. VRST

'08,123-129.

30. Subramanian, S., et al. 2006. Multi-layer interaction for

digital tables. UIST '06, 269-272.

31. Theremin, L.. 1928. Method of and apparatus for the

generation of sounds. U.S. Patent No. 1,661,058..

32. Uno, Y., Mitsuo, K., and Rika S., 1989. Formation and

control of optimal trajectory in human multijoint arm

movement. Biological Cybernetics, 61, 89-101.

33. Wigdor, D., and Wixon, D.. Brave NUI World: Designing

Natural User Interfaces for Touch and Gesture, 1 ed.

Morgan Kaufmann, Apr. 2011.

34. Wilson A.. 2010. Using a depth camera as a touch sensor.

ITS '10, 69-72.

35. Wilson, A.. 2004. TouchLight: An imaging touch screen

and display for gesture-based interaction. ICMI '04,69-76.

36. Wobbrock, J., Cutrell, E., Harada, S., and MacKenzie, S..

2008. An error model for pointing based on Fitts' law. CHI

'08, 1613-1622.

37. Yang, X., Grossman, T., Irani, P., and Fitzmaurice,G.2011.

TouchCuts and TouchZoom: Enhanced Target Selection

for Touch Displays using Finger Proximity Sensing. CHI

'11, 2585-2594.

We would like to thank members of DGP and Tactual Labs

for their support of the project. We also thank Kate Dowd

for her writing assistance.

REFERENCES

1. http://news.softpedia.com/news/The-Average-Web-PageLoads-in-2-45-Seconds-Google-Reveals-265446.shtml

2. http://www.samsung.com/global/microsite/galaxys5/

Samsung Galaxy S5

3. Annett, M., et al. 2011. Medusa: a proximity-aware multitouch tabletop. UIST '11, 337-346.

4. Baudisch, P., et al. 2003. Drag-and-Pop and Drag-andPick: techniques for accessing remote screen content on

touch- and pen-operated systems. INTERACT '03, 57-64.

5. Buxton, W. 1990. A Three-State Model of Graphical Input.

INTERACT '11, 449-456.

6. Dietz, P., and Leigh, D.. 2001. DiamondTouch: a multiuser touch technology. UIST '01, 219-226.

7. Fitts M.. 1954. The information capacity of the human

motor system in controlling the amplitude of movement. J.

of Experimental Psychology, Vol 47, N6,. 381–391.

8. Fitzmaurice, G., Ishii, H., and Buxton, W. 1995.. Bricks:

laying the foundations for graspable user interfaces.

CHI’95, 442-449.

9. Fitzmaurice, G., Khan, A., Pieké, R., Buxton, B.,

Kurtenbach, G..2003. Tracking Menus. UIST '03, 71-79.

10. Flash T., and Hogan N.. 1985. The Coordination of Arm

Movements: An Experimentally Confirmed Mathematical

Model. Journal of Neurosciences. Vol 5. N7, 1688-1703.

11. Forlines, C. and Balakrishnan, R.. 2008. Evaluating tactile

feedback and direct vs. indirect stylus input in pointing and

crossing selection tasks. CHI '08. 1563-1572.

12. Funahashi, T., Toshiaki S., and Tsuguya Y.. 1989. Position

detecting apparatus. U.S. Patent No. 4,878,553.

13. Galloway, J. & Koshland, G.. 2002. General coordination

of shoulder, elbow and wrist dynamics during multijoint

arm movements. Exp. Brain Rsch, Vol 142,163-180.

14. Grosse-Puppendahl, T. et al. 2013. Swiss-cheese extended:

an object recognition method for ubiquitous interfaces

based on capacitive proximity sensing. CHI '13.

15. Grossman, T., Hinckley, K., Baudisch, P., Agrawala, N.,

and Balakrishnan, R.. 2006. Hover widgets: using the

tracking state to extend the capabilities of pen-operated

devices. CHI '06, 861-870.

16. Grossman, T., Wigdor, D., and Balakrishnan, R. 2004

Multi finger gestural interaction with 3D volumetric

displays. UIST '04, 61-70.

17. Hachisu, T. and Kajimoto, H.. 2013. HACHIStack: duallayer photo touch sensing for haptic and auditory tapping

interaction. CHI '13, 1411-1420.

18. Hilliges O. et al. 2009. Interactions in the air: adding

further depth to interactive tabletops. UIST '09, 139-148.

214