reasonably practicable

Revisiting the compliance standard of “reasonably practicable” in the model Work Health and Safety Act

By Barry Sherriff

INTRODUCTION

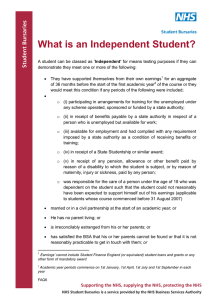

Occupational health and safety (OHS) laws are aimed at ensuring the protection of workers and others through the effective management of risk. Duties of care are placed on various parties, requiring them to achieve outcomes to a prescribed standard. The standard for most duties is “reasonably practicable”.

The standard of reasonably practicable is well known to those who practice in OHS, whether as a lawyer or as an OHS professional. However, it is often not well understood by the duty holders who must meet that standard to comply with their legal obligations.

The model Work Health and Safety Act (the model Act), to be introduced in all Australian jurisdictions from 1 January 2012, includes a definition of reasonably practicable that is intended to codify and clarify the interpretation of that expression by courts over many decades. The model Act definition is consistent with, but expands on, definitions currently found in OHS legislation in a number of States.

THE APPLICATION OF A ‘REASONABLY PRACTICABLE’ AS A STANDARD OF CONDUCT

The regulation of OHS in Australia is based on duties of care placed on persons who, in the course of conducting a business or undertaking, have work done for them (most commonly as an employer), or who do or provide things necessary for work to be done (e.g. designers, manufacturers, suppliers, those who manage or control a workplace)

1

.

These duties of care are not prescriptive – they do not tell the duty holder what they must do. The duties are performance or outcome based, identifying the activities and elements with respect to which risk to the health or safety of persons must be eliminated or minimised

2

. The duty holder must determine what must be done to achieve the required outcomes.

The legislation in each jurisdiction provides for compliance with these duties, or a defence to a prosecution for a breach of the duties

3

, through taking action to eliminate or minimise OHS risks ‘so far as is reasonably practicable’

4

. This will be referred to in this article as the standard of conduct to be achieved, or the qualifier of the duties of care.

‘REASONABLY PRACTICABLE’ IN THE MODEL WORK HEALTH AND SAFETY ACT

The model Act is the result of a process commencing with the National Review into Model

Occupational Health and Safety Laws (the Review). The panel that undertook the Review considered at length whether reasonably practicable should continue to be the standard of conduct or qualifier of the duties of care, and how it should be defined

5

.

1

Those who undertake the work (most commonly referred to as employees) also have a duty of care, to take reasonable care for themselves and others who may be affected by their acts or omissions at work.

2

For example, an employer must provide and maintain a safe working environment for its employees, including providing for various matters such as the provision and maintenance of safe systems of work, safe plant and a safe workplace (See e.g. Occupational Health and Safety Act 2000 (NSW) s 8:

Occupational Health and Safety Act 2004 (Vic) s 21; Occupational Health and Safety Act 1986 (SA) s

19).

3

See e.g. Occupational Health and Safety Act 2000 (NSW) s 28; Workplace Health and Safety Act

1995 (Qld) s 37. This is generally, although not entirely accurately, described as placing a ‘reverse onus’ of proof on the duty holder to prove that they are innocent of what is otherwise described as a strict liability offence.

4

In some jurisdictions this is simply referred to as ‘practicable’ and in Queensland is expressed as

‘reasonable precautions’.

5

The panel also considered the more controversial issue whether that qualifier should be contained within the duties of care (the prosecution being required to prove a failure by the duty holder to meet the standard) or as an element of a defence. The panel chose the former approach, which is adopted in the model Act.

APAC-#8379074-v1

- 2 -

The panel, after considering submissions and consulting broadly with representatives of regulators, unions and industry bodies, recommended that reasonably practicable be used to qualify the duties of care placed on a person conducting a business or undertaking (PCBU), and that the qualifier should be defined.

6

The concept of reasonably practicable is not the sole determinant of the standard of conduct required by a PCBU under the model Act, and should be considered together with other significant provisions of the model Act. Considering those other relevant sections enables a better understanding of the operation of how reasonably practicable is to be applied.

The objects of the model Act include

7

that “…regard must be had to the principle that workers and other persons be given the highest level of protection against harm to their health, safety and welfare from hazards and risks… as is reasonably practicable …”.

(emphasis added).

Principles in the model Act that apply to the duties of care include a reference duty-holder being required to

8

to each concurrent

“…discharge the person’s duty to the extent to which the person has the capacity to influence and control the matter…”

The principles also provide

9

that

“A duty on a person to ensure health and safety requires the person: a) to eliminate risks to health and safety, so far as is reasonably practicable; and b) if it is not reasonably practicable to eliminate risks to health and safety, to minimise those risks so far as is reasonably practicable.”

These objects and principles must be taken into account when interpreting and applying the qualifier of reasonably practicable. They ensure that a duty holder must start by identifying the highest level of protection that they are able (legally and practically) to achieve, and that the duty holder should only take action that achieves only a lower level of protection to the extent that it is reasonable to do so.

10

AN ENHANCED DEFINITION

Reasonably practicable is defined in Section 18 of the model Act. The panel considered that understanding this qualifier, together with the objects and principles noted above, allows a PCBU to understand what the duty of care requires, and also how to go about meeting the standard. The elimination or minimisation of risk is a keystone of OHS laws, including the model Act, and the process for determining what is reasonably practicable is consistent with and should support that objective.

While current definitions

11

provide some guidance as to the matters to be considered, they do not make clear the intellectual process to be undertaken, or the standard to be reached. While courts have consistently interpreted reasonably practicable over many decades

12

, this does not assist the duty holders who do not have ready access at the workplace to court decisions, or the ability to understand those decisions.

Accordingly, the panel recommended a more expansive definition and provided an example clause which has been substantially adopted in the model Act

14

.

13

6

For a discussion of this issue and the recommendations of the panel, see National Review into

Model Occupational Health and Safety Laws: First Report to the Workplace Relations Ministers’

Council October 2008 , Commonwealth of Australia, 2008 (the First Report), Chapter 5.

7

See s 3(2) of the model Act.

8

9

See s16(3)(b) of the model Act.

See s17 of the model Act.

10

This approach is adopted in the ‘Workplace Position: How WorkSafe applies the law in relation to

Reasonably Practicable’, issued under Occupational Health and Safety Act 2004 (Vic) s 12, when considering the question of cost.

11

See e.g. Occupational Health and Safety Act 2004 (Vic) s 20(2); Occupational Safety and Health

Act 1984 WA s 3

12

See Edwards v National Coal Board [1949] 1 KB 704; R v Associated Octel Limited [1994] 4 All ER

1051; Slivak v Lurgi (Australia) Pty Ltd [2001] ALR 585; R v Australian Char Pty Ltd [1999] 3 VR 834;

Holmes v RE Spence & Co Pty Ltd [1992] 5 VIR 119; WorkCover Authority of NSW v Cleary Bros

(Bombo) Pty Ltd [2001] 110 IR 182; and the discussion on reasonably practicable in B Sherriff OHS in

Practice – A Guide to Legislation in Victoria (Anstat, Melbourne, 2010) at 3-2 to 3-19; and C Maxwell,

Occupational Health and Safety Act Review (March 2004) pages 101 to 109.

13

At paragraph 5.55 of the First Report.

APAC-#8379074-v1

- 3 -

SPECIFYING THE STANDARD AND THE PROCESS TO BE UNDERTAKEN

The definition of reasonably practicable in the model Act provides guidance as to the standard to be reached, by noting that it means

“…that which is, or was at a particular time, reasonably able to be done in relation to ensuring health and safety…”

This comprises two elements – what is able to be done (possible) and the extent to which the things which can be done are reasonable in the circumstances.

15

This is consistent with the object, noted above, of providing the highest level of protection that is reasonably practicable.

The definition in the model Act gives guidance on the thought process to be undertaken, by providing that the standard is to be determined by

“…taking into account and weighing up all the relevant matters…”

The reference to ‘weighing up the relevant matters’ is included in definition of reasonably practicable to provide guidance on the intellectual process to be undertaken. Simply referring to ‘taking into account’ the various matters does not clearly direct how the duty holder is to those matters into consideration to reach a conclusion as to what should be done in the circumstances.

Taking the various matters into account will assist the duty holder to determine what is able to be done. Weighing up those considerations enables the duty holder to then determine whether it is reasonable not to do so.

THE MATTERS TO BE CONSIDERED

The following is a summary of the matters that are listed in the definition in the model Act as matters that are required to be taken into account and weighed up, when determining what is, or was, reasonably practicable. It is important to note that this list is inclusive, not exclusive. This means that other matters may be significant and should be considered. The significance of this is demonstrated below, in the discussion of the issue of control.

All of the matters must be considered, together with each of the other matters.

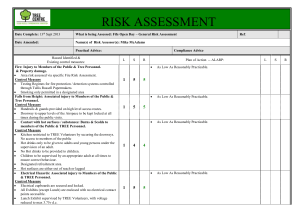

a) The likelihood of the hazard or the risk concerned occurring

This is relevant to determining whether applying a particular means of eliminating or minimising risk (risk control), or alternative or combination of risk controls is reasonable. The more remote the likelihood of harm, the less it may be considered to be reasonable to expend significant amounts of time, effort or money on risk controls. b) The degree of harm that might result from the hazard or the risk

This is relevant to determining whether applying a particular risk control or controls, or a choice between risk control options, is reasonable. The more serious the outcome (e.g. death or serious injury) the harder it is to justify not taking available action to eliminate or minimise the risk of that harm.

c) What the person concerned knows, or ought reasonably to know, about:

(i)

(ii) the hazard or the risk; and ways of eliminating or minimising the risk

This is relevant to both elements, determining what the particular duty holder is able to do, and what is reasonable for them to do. If the duty holder lacks the knowledge of the risk or risk controls, then they are unable take action to control the risk. The lack of knowledge will at the very least mean that it is or was not reasonable to expect the duty holder to do what is possible to control the risk.

It is important to note that it is not only the actual knowledge of the person that is to be considered, but also what the person ought reasonably to know. Information that is available to other PCBUs who operate in the relevant industry, and would reasonably be expected to be known by the duty holder, must be taken into account. A duty holder should accordingly make such enquiries as may be necessary to obtain that knowledge.

d) The availability and suitability of ways to eliminate or minimise the risk

14

15

See s 18 of the model Act.

For an earlier discussion of these elements of reasonably practicable see C Maxwell, Occupational

Health and Safety Act Review (March 2004) pages 101 to 104.

APAC-#8379074-v1

- 4 -

This is relevant to both elements - determining what the particular duty holder is able to do, and what is reasonable for them to do. What risk controls are available will determine what is able to be done.

If particular controls that are available are unsuitable (will not work effectively in the particular environment or may introduce other risks) then it may not be reasonable to require the risk controls to be applied.

The suitability of risk controls may also go to reasonableness, being relevant to choosing between risk control options. A duty holder may choose the risk control that is most suitable from the range of controls or combinations of controls that each provide an equivalent and appropriate level of risk control.

e) After assessing the extent of the risk and the available ways of eliminating or minimising the risk, the cost associated with available ways of eliminating or minimising the risk, including whether the cost is grossly disproportionate to the risk.

Cost is a matter that is relevant to the reasonableness of a person not doing all that can be done to eliminate or minimise a risk. Current definitions of reasonably practicable do not, however, explain how cost is to be taken into account.

The model Act definition assists by making it clear that: a) Cost is only to be considered after all other matters. This means that a duty holder must first consider what is known, what can be done, how severe the outcome may be if the risk eventuates, and how likely that is to occur. These factors together will determine what can be done and would ordinarily be expected to be done, if cost is not a consideration.

b) Each of the available and suitable risk controls, or combinations of risk controls, should be considered and cost may be a factor in deciding which of the available controls may reasonably be applied.

The requirement that the highest level of protection that is reasonably practicable should be noted, however, with cost not being used to justify a choice of risk control(s) that provides for a lesser potential for risk elimination or a lower level of risk minimisation.

c) The relevance of the proportionality between the risk and the cost of risk controls is to be limited to circumstances where the cost is grossly disproportionate to the risk. For example, there is a low likelihood of a minor injury and the cost of a particular risk control (engineering control) will be very high and therefore not reasonably incurred.

This is consistent with court decisions, which make it clear that cost – other than in relation to the choice between risk control options that provide the same level of risk control – should not justify a failure to take available measures where there is at least a moderate likelihood of at least a moderately serious injury or death.

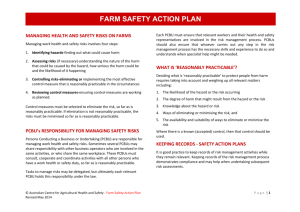

The practical process to adopt to determine what is or was reasonably practicable in the circumstances is:

1. What is known about the hazards and risks, and risk controls, associated with the relevant activity?

2. How serious and likely can the harm be?

3. What controls, alone or in combination, are both available and suitable in the circumstances? What can be done to eliminate or minimise the risk?

4. Given what is known about the severity of the hazards and risks and the ways in which the risk may be eliminated or minimised, what risk control or combination will most effectively control the risk (likelihood and extent of control)?

5. Are there reasons why a risk control or combination of controls may not reasonably be required in the circumstances, for example by reason of a lack of ability to control or disproportionately high costs? Is there another control or combination of controls that may achieve the same level of risk control? If the highest level of risk control is not reasonable, is the risk so moderate as to allow a lower level of risk control to be acceptable (e.g. relying on less certain risk control by systems and training rather than engineering where the risk is a low chance of minor injury)?

APAC-#8379074-v1

- 5 -

‘CONTROL’ IS RELEVANT TO DETERMINING WHAT IS REASONABLY ABLE TO BE DONE

A controversial issue for the panel was the role, if any, of the ‘control’ able to be exercised by a duty holder, in determining the duties of care or the standard of conduct to be reached

16

. The panel’s recommendation that the definition of reasonably practicable not refer to ‘control’ was accepted by the

Workplace Relations Ministers’ Council and the model Act definition does not directly make reference to control as a matter to be taken into account.

The panel did, however, make it clear that the reason for not referring to control in the definition was not to suggest that control should not be a relevant factor. To the contrary, the panel noted that control is implicit in the definition of reasonably practicable in many ways.

A duty holder may not be able to take action (at all or specific steps) to eliminate or minimise risk, where they lack the legal entitlement or practical ability to control or influence relevant matters. It may not be reasonable to expect a duty holder to take action in some circumstances, even though they may be able to do so in other circumstances or other people may be able to do so, where this flows from a lack of or limitation on, the control or influence they are able to exercise over relevant matters.

The reference in the model Act definition to what is or was reasonably able to be done allows, if not requires that control be considered, where relevant.

Clearly then, control is a “relevant matter” to be taken into account in determining what is reasonably practicable in the circumstances. The panel considered there to be direct judicial support for this

17

and a review of cases demonstrates that in practice control is regularly taken to be a relevant factor.

What is important is that the panel made it clear that the drafting of the example clause, adopted in the model Act, was intended to provide for control to be taken into account, without specifically prescribing it. The reasons given by the panel for not including control in the list of relevant matters were that:

control is an inherent element of reasonably practicable; and

by including control in the list, that matter may be given undue prominence by duty holders, and may encourage duty holders to artificially manipulate control to seek to limit what they must do to comply with the relevant duty.

The Workplace Relations Ministers’ Council, and the drafters of the model Act, agreed with that approach when adopting the example definition.

CONCLUSION

Where the law requires a person to achieve outcomes, without prescribing detailed processes, it is important that the person required to comply can readily understand what is expected of them. The law should make clear what the required standard is, and the process by which that standard is determined. This is done in OHS laws by the use of a qualifier of reasonably practicable.

The model Act includes a definition that builds on those in current usage, to provide clarity around both the standard and the process. The definition is consistent with and supports the objects and principles set out in the model Act.

While the definition should provide sufficient guidance for duty holders, the discussion of the panel in its First Report provides further guidance on how a duty holder can identify what they must do to comply. Importantly, the enhanced definition should assist in the effective management of OHS risks by those who direct or influence matters that influence the level of health and safety protection.

Barry Sherriff LLB (Hons) (Melb), LLM (Mon), FSIA

Partner, Norton Rose Australia, Solicitors

Panel Member, National Review into Model Occupational Health and Safety Laws

16

See the discussions in the First Report at paragraphs 5.57 to 5.64 and paragraphs 6.71 to 6.79. See also the earlier discussion on difficulties associated with the use of control in duties of care in B

Sherriff “The concept of control in determining OHS responsibilities: A need for clarity”, 2007, 35 ABLR

298.

17

See the discussion in paragraph 5.59 of the First Report and in footnote 31.

APAC-#8379074-v1