micro, small, and medium enterprises

advertisement

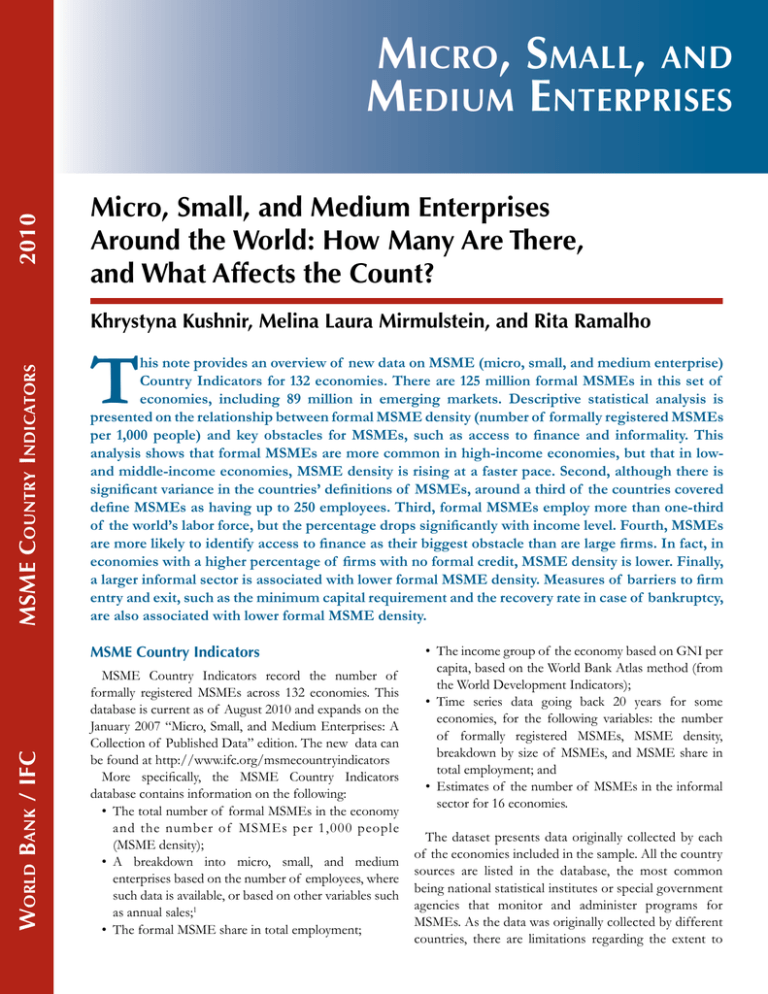

2010 Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises Around the World: How Many Are There, and What Affects the Count? MSME Country Indicators Khrystyna Kushnir, Melina Laura Mirmulstein, and Rita Ramalho T his note provides an overview of new data on MSME (micro, small, and medium enterprise) Country Indicators for 132 economies. There are 125 million formal MSMEs in this set of economies, including 89 million in emerging markets. Descriptive statistical analysis is presented on the relationship between formal MSME density (number of formally registered MSMEs per 1,000 people) and key obstacles for MSMEs, such as access to finance and informality. This analysis shows that formal MSMEs are more common in high-income economies, but that in lowand middle-income economies, MSME density is rising at a faster pace. Second, although there is significant variance in the countries’ definitions of MSMEs, around a third of the countries covered define MSMEs as having up to 250 employees. Third, formal MSMEs employ more than one-third of the world’s labor force, but the percentage drops significantly with income level. Fourth, MSMEs are more likely to identify access to finance as their biggest obstacle than are large firms. In fact, in economies with a higher percentage of firms with no formal credit, MSME density is lower. Finally, a larger informal sector is associated with lower formal MSME density. Measures of barriers to firm entry and exit, such as the minimum capital requirement and the recovery rate in case of bankruptcy, are also associated with lower formal MSME density. World Bank / IFC MSME Country Indicators MSME Country Indicators record the number of formally registered MSMEs across 132 economies. This database is current as of August 2010 and expands on the January 2007 “Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises: A Collection of Published Data” edition. The new data can be found at http://www.ifc.org/msmecountryindicators More specifically, the MSME Country Indicators database contains information on the following: • The total number of formal MSMEs in the economy and the number of MSMEs per 1,000 people (MSME density); • A breakdown into micro, small, and medium enterprises based on the number of employees, where such data is available, or based on other variables such as annual sales;1 • The formal MSME share in total employment; • The income group of the economy based on GNI per capita, based on the World Bank Atlas method (from the World Development Indicators); • Time series data going back 20 years for some economies, for the following variables: the number of formally registered MSMEs, MSME density, breakdown by size of MSMEs, and MSME share in total employment; and • Estimates of the number of MSMEs in the informal sector for 16 economies. The dataset presents data originally collected by each of the economies included in the sample. All the country sources are listed in the database, the most common being national statistical institutes or special government agencies that monitor and administer programs for MSMEs. As the data was originally collected by different countries, there are limitations regarding the extent to which the data can be standardized. Where possible, MSMEs are defined as follows: micro enterprises: 1–9 employees; small: 10–49 employees; and medium: 50–249 employees. However, in the majority of countries, this definition did not match the local definition, in which cases the local definition took precedence. Only firms with at least one employee are included. Of the 132 economies covered, 46 economies define MSMEs as those enterprises having up to 250 employees. For 29 economies, variables other than total employment are used or an MSME definition is not available (Figure 1). Among such other variables are the number of employees differentiated by industry, annual turnover, and investment. Not surprisingly, the overwhelming majority of formal MSMEs globally are micro enterprises, with 83 percent of all MSMEs in this category.2 The data covers only the formal registered sector (except for 16 economies where data is available). This is an important limitation given that informal MSMEs, especially in developing countries, often outnumber formal MSMEs many times over. For example, in India in 2007, there were fewer than 1.6 million registered MSMEs and 26 million unregistered MSMEs, that is, about 17 unregistered MSMEs for every registered one. Important lessons were drawn from the MSME data while building the MSME Country Indicators, in particular the following: Figure 1 Distribution of the MSME Definition by Number of Employees A third of the economies (out of 132 covered) define MSMEs as having up to 250 employees. <499 <299 Number of Employees <250 <200 ■ East Asia and the Pacific [10] Europe and Central Asia [14] ■ High-income: OECD members [28] ■ <149 <100 Latin America and the Caribbean [15] Middle East and North Africa [9] ■ High-income: Non-OECD economies [14] ■ <79 ■ <60 ■ <50 ■ South Asia [3] Sub-Saharan Africa [10] <19 0 10 20 30 40 50 Number of Economies Source: MSME Country Indicators. Note: Name of the region [#] signifies the number of economies from the region included in the analysis. The figure uses data from 103 economies.3 2 • MSME data are not always standardized across countries and time. Data on MSMEs are gathered by various institutions using different methods. These institutions define MSMEs based on differing variables and scales and sometimes change their definitions. EUROSTAT’s Structural Business Statistics provides the best example of regional coordination and harmonization of MSME data. In order to have comparable MSME data, the following steps could be taken: • Economies should be surveyed using a unified and standardized method; • Institutions in charge of gathering MSME data should coordinate with each other regarding the variables and methods used to determine the size of the MSME sector. • These actions can be taken first at the regional level and secondly expanded to the global level. In return, economies would reap the benefits of a cross-country and time-series analysis of MSMEs’ contribution to development. • MSME data on the informal sector are scarce and are not comparable across countries. This is due to differences in the definition of the informal sector and in estimation methods. Estimates of the informal sector are needed in order to make a comprehensive evaluation of the MSMEs’ contribution to economic development. This data gap could be filled by surveying MSMEs operating in the informal sector or by encouraging institutions that collect MSME data on the formal sector to also develop estimates of the size of the informal sector. • Time series data is not always available. However, it is crucial for future evaluation of the reforms of business regulations. • Some institutions collect data on MSMEs only in selected sectors, most often in manufacturing. This limits the possibilities of evaluating MSMEs’ contribution to gross domestic product (GDP) or employment. For more details on the methodology, please refer to “Methodology note on the MSME Country Indicators.”4 Where are MSMEs Most Common? In the 132 economies covered, there are 125 million formal MSMEs of which 89 million operate in emerging markets. These results are in line with a recent study published by IFC and McKinsey & Company in 2010, “Two Trillion and Counting,” which found that there are between 80 and 100 million formal MSMEs in emerging markets. Figure 2 MSME Density Across the World Europe and Central Asia [18] 6,667,715 MSMEs High-income: OECD members [29] 36,878,280 MSMEs Latin America and the Caribbean [16] 13,763,465 MSMEs Middle East and North Africa [7] 4,488,767 MSMEs South Asia [3] 7,451,803 MSMEs East Asia and the Pacific [11] 39,293,783 MSMEs High-income: Non-OECD economies [19] 1,848,282 MSMEs Sub-Saharan Africa [13] 13,154,122 MSMEs MSMEs per 1,000 people 1-10 11-20 21-30 31-40 41-50 51 and above No data avilable Sources: MSME Country Indicators. Note: Name of region [#] signifies the number of economies from the region included in the analysis. The figure uses the most recent data available after the year 2000. The figure use data for 116 economies.5 On average, there are 31 MSMEs per 1,000 people across the 132 economies covered. The five countries with the highest formal MSME density are as follows: Brunei Figure 3 MSME Density and Income per Capita Economies with higher income per capita tend to have more MSMEs per 1,000 people. Figure 4 Median MSME Density by Region IDN 100 PRY CZE ECU JAM MWI The regional distribution of MSME density is in line with income level distribution. ISL GRC MUS ITA KORESP NGA 60 PRT HUN BOL CYP SVN NOR LUX Median MSME Density 80 MSME Density Darussalam (122), Indonesia (100), Paraguay (95), the Czech Republic (85), and Ecuador (84). Overall, economies with higher income per capita tend to have more formal MSMEs per 1,000 people (Figure 3). This result is in line with data previously presented in the literature. Klapper et al. (2008) find that business density (which includes both MSMEs and large firms) is positively correlated with JFN ARMBH CHL LTU ERA CHE HKG AUS MF POL MNE URY TUR EST NZL AUT THA BGR MLD EGY COL SAU ISR BWA SLV GBR WBG JOR MAR BER TJK MKD BRA DEUIRL AZE ROM BGD YEMPAK HRV DZA KYZ ARE PTO KWT CRI UZB ARG MDA STK SRB RUS PH UKR RWA BLR LAO TMPCMR LBN VEN OMN KCZ DOM MOZ IND SDN KEN 40 HND VNM 20 0 0 6 8 10 GNI per Capita, Atlas Method (log) 12 Sources: MSME Country Indicators, World Development Indicators. Note: The results of the regression are statistically significant at the 5 percent level. The figure uses the most recent data available after the year 2000. The figure uses data from 109 economies.6 45 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 Sub-Saharan East Asia South Asia Africa & the Pacific [3] [14] [11] Europe & Middle East High-Income: Latin America High-Income: Central Asia & North Africa Non-OECD & the Caribbean OECD [18] [7] economies [16] members [19] [29] Source: MSME Country Indicators. Note: Name of the region [#] signifies the number of economies from the region included in the analysis. The figure uses the most recent data available from 117 economies7 after the year 2000. 3 income per capita. It is important to note that the analysis presented in this note refers only to correlations and that no causal inferences should therefore be made. The regional distribution of MSME density is in line with the income level distribution. Consequently, Sub-Saharan Africa and high-income OECD economies are at opposite ends of the spectrum with regard to MSME density (Figure 4). Somewhat surprisingly, Latin America and the Caribbean have more MSMEs per 1,000 people than non-OECD high-income economies. However, once the countries that are heavily dependent on mineral resources (United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Oman, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia) are excluded from the sample, the MSME density for non-OECD high-income economies is at a similar level to that for Latin America and the Caribbean. Globally, the number of MSMEs per 1,000 people grew by 6 percent per year from 2000 to 2009 (Figure 5). Europe and Central Asia experienced the biggest boom, with 15 percent growth. Such a fast pace may have resulted from the continuation of post-Soviet privatization in these economies. Another possible contributing factor may be the accession of the Eastern European economies to the European Union (EU). When considering the MSME growth rate from the standpoint of income per capita (Figure 6), high- income economies grew three times slower than low-income economies and five times slower than lower-middleincome economies. This could be explained by the fact that Figure 5 high-income economies start from a higher base, which is why the growth rate appears slower. In fact, even when taking into account differences in income level, economies with lower bases grow at higher rates.8 Only low-income economies do not follow the pattern of “higher income – slower growth rate” when compared to middle-income economies, which could be because the informal sector absorbs more MSMEs in low-income economies than in upper- and lower-middle-income countries. In the high-income economies, MSMEs are not only denser in the business structure, but also employ a higher percentage of the workforce. In half of the high-income economies covered, formal MSMEs employed at least 45 percent of the workforce, compared to only 27 percent in low-income economies (Figure 7). These indicators highlight the importance of MSMEs to economic development and job creation. Formal MSMEs employ more than one-third of the global population, contributing around 33 percent of employment in developing economies. From a regional perspective (Figure 8), East Asia and the Pacific have the highest ratio of MSME employment to total employment. This is mainly driven by China, where formal MSMEs account for 80 percent of total employment. The low ratio of formal MSME employment to total employment in South Asia could be explained by the fact that in the three countries covered, Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan, the informal sector is large. Figure 6 MSME Growth by Region, 2000-2009 18 16 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 High-Income: Latin America Sub-Saharan High-Income: East Asia OECD members & the Pacific Non-OECD & the Caribbean Africa [5] [24] economies [2] [4] [9] Middle East & North Africa [2] Europe & Central Asia [14] Global [60] Source: MSME Country Indicators. Note: Name of the region [#] signifies the number of economies from the region included in the analysis. The figure uses data for 60 economies. Data on economies that met the next criteria were included in the analysis: (i) if the MSME definition remained unchanged from 2000 to 2009; (ii) if there were data available for both time periods of 2000–2004 and 2005–2009. 4 The MSME growth rate is three times lower in high-income economies, than in low-income economies. Annual MSME Growth Rate Annual MSME Growth Rate Globally, MSMEs grew at a rate of 6 percent per year from 2000 to 2009. MSME Growth Rate by Income Group, 2000-2009 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 High [26] Upper-middle [13] Lower-midlle [15] Low [6] Income Group Source: MSME Country Indicators. Note: Name of the income group [#] signifies the number of economies from the income group included in the analysis. The figure uses data from 60 economies. Data on economies which met the next criteria were included in the analysis: (i) if the MSME definition remained unchanged from 2000 to 2009; (ii) if there were available data in both time intervals of 2000-2004 and 2005-2009. Key Obstacles for Firms and their Connection to MSME Density Upper-middle [26} Lower-midlle [18] Low [20] Income Group Source: MSME Country Indicators, World Development Indicators database. Note: Name of the income group [#] signifies the number of economies from the income group included in the analysis. The figure uses the most recent data available after the year 2000. The figure uses data from 103 economies.9 The results of the regression are statistically significant at the 5 percent level. Figure 8 MSME Employment vs. Total Employment Figure 9 Electricity and access to finance are the two most cited obstacles for businesses in developing countries, and access to finance affects small businesses much more than it does medium and large businesses. 800 600 400 200 0 South Asia Middle East Europe & Latin America High-Income: Sub-Saharan High-Income: East Asia [3] & North Africa Central Asia & the Caribbean Non-OECD Africa & the Pacific OECD [6] [16] economies [8] [10] [13] members [18] [28] MSME Employment Total Employment Source: MSME Country Indicators. Note: Regions are grouped in ascending order based on the ratio of the MSME employment to total employment. Name of the region [#] signifies the number of economies from the region included in the analysis. For the following economies the number of employed by the MSMEs was calculated from the reported percentage of the total employment: Armenia, China, Ecuador, Ghana, Iceland, Israel, Jamaica, Nigeria, Myanmar, Malawi, Malaysia, Pakistan, Singapore, Peru, Uzbekistan and South Africa. The figure uses the most recent data available after the year 2000, from 102 economies.10 16 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 SMall Medium Large 1,000 18 Overall % of Firms Identifying Obstacle X as the Biggest Obstacle Number of People Employed (in millions) In China, MSMEs provide 80 percent of the total employment, driving East Asia and the Pacific to be the leader in the ratio of MSME employment to total employment. 1,200 Six Most Commonly Cited Obstacles by Firms (out of 15) Electricity Access to Practices of Tax Rates Finance the Informal Sector Political Instability SMall Medium Large High [39] Overall 0 SMall Medium Large 10 Overall 20 SMall Medium Large 30 Overall 40 SMall Medium Large Median MSME Employment 50 Overall Formal MSMEs employ more than one third of the world’s labor force, but the percentage drops significantly with income level. The World Bank Enterprise Surveys dataset was used to identify the biggest obstacles for firms worldwide. This dataset covers 98 countries, using the same sampling and surveying methodology. It produces representative estimates for the non-agriculture private sector economy and allows for comparisons of firms of different sizes within a country and globally. The Enterprise Survey data covers several aspects of the business environment and includes both objective and perception-based questions. Among other things, Enterprise Surveys measure the biggest obstacles for firms of all sizes from a list of 15 potential obstacles. In the Enterprise Surveys dataset, firms are divided into the following categories: small (5 to 9 employees), medium (10 to 99 employees), and large (100 or more employees). Although this categorization may not match the country-level definitions used in the MSME Country Indicators database, the information presented in Enterprise Surveys can still be indicative of the key obstacles facing small and medium-sized firms. SMall Medium Large Median MSME Employment (percentage of the total) by Income Group Overall Figure 7 Corruption Source: Enterprise Surveys Dataset. Note: The data cover 98 countries. The 15 obstacles are access to finance; access to land; business licensing and permits; corruption; courts; crime, theft and disorder; customs and trade regulations; electricity; inadequately educated workforce; labor regulations; political instability; practices of competitors in the informal sector; tax administration; tax rates and transport. 5 Figure 10 MSME Density and Enterprises Unserved by the Credit Institutions Figure 11 The smaller the percentage of financially unserved firms, the higher the formal MSME density on average. 100 MSME density increases with SME lending. 100 IDN IDN PRY ECU 80 PRY PRT ISL 80 ITA ESP HUN NOR LUX SVN 40 FIN BOL CHI ARM BELFRASWEBOK TUR GBR LTU HND ZAF URY MEX VNM NLDBGR COL BWA LVA SLV PER RUN NFL DEO BRA HRV 20 TJK SRB ARG PHL 0 0 AZE 2 YEM UZB MDA UKR RWA BFA KGZ CMR 4 CHN UGA GHA 6 MOZ 8 Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises Unserved by the Credit Institutions (weighted average (percentage of firms)) CZE ECU MWI MSME Density MSME Density MUS 60 MSME Density and SME Lending/ GDP JAM PRT GRC MUS ITA 60 NGA LUX BOL CHL KEN ARM IDN IDN IDN FRA OHL FIN AUS POL SWE ZAF MNE URY MEX TUR AUTOGP IDN BGR BWA COLSLVEGY IDN USR MAR JOR PER TJK MK ROM IDN AZE DEU MYS IDN IDN BGD 20 YEM IDN HRV KAZ DZA TTO AWT ARG SRH IDN IDN IDN PHL TUS UKR UGA IDN IDN LAG IDN IDN IDN IDN IDN IDN IDN AND TUN 0 SDN 40 HKG 0 KOR ESP HUN CYP SVN JPN BEL EST THA CAN DNK GBR NZL LVA NLD CHN .2 .4 .6 SME Lending/GDP Source: MSME Country Indicators, IFC and McKinsey & Company 2010. Note: The results are statistically significant at the 5 percent level, while controlling for GNI per capita (log) and if an outlier–Indonesia–is dropped. The figure uses data from 52 economies. Included economies: (i) covered in both databases; (ii) data were not extrapolated; (iii) with available GNI per capita, Atlas method. Source: MSME Country Indicators, Financial Access 2010 (Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP)). Note: The figure uses data from 101 economies. The results of the regression are statistically significant at the 5 percent level. When controlling for GNI per capita, Atlas method (log), the results are not statistically significant at the 5 percent level. Data for some countries were estimated by the CGAP. Included economies: (i) covered in both databases; (ii) with available GNI per capita, Atlas method. When presented with a list of 15 possible obstacles, electricity and access to finance are the two most-cited by businesses in developing countries (Figure 9). Firms of different sizes rank obstacles differently. Access to electricity is a significant constraint overall and affects small, medium, and large enterprises alike. However, more small businesses list access to finance as their biggest obstacle than do medium enterprises, and fewer large firms see it as their biggest obstacle. On the other hand, political instability is more often identified as the biggest obstacle by large firms than by small ones. It should be borne in mind that this information is based on the perceptions of firms and that it is therefore important to check if it is corroborated by objective measures: Are MSMEs in fact more common where they have easier access to credit? Are they more common where the informal sector is smaller? overdraft, but do not have one—is smaller (Figure 10). This finding matches the firm-level data that identifies access to finance as one of the most commonly cited obstacles, in particular by small and medium enterprises (SMEs). MSME density is not only correlated with whether or not credit is used, but how much. MSME density is lower in economies where MSMEs have some access to credit, but where it is not sufficient (underserved). Furthermore, where SME lending (as a share of GDP) increases, MSME density also increases (Figure 11). Access to Finance Formal MSME density is on average higher in countries where the percentage of financially unserved firms—that is, those that would like to have a loan or 6 Practices of Informal Sector and Corruption Competition from the informal sector and corruption among government officials also pose significant challenges for firms. Objective measures of the size of the informal sector, barriers to entry into and exit from the formal market, and the existence of informal payments shed light on the importance of these obstacles to the existence of MSMEs. First, the larger the informal sector in an economy, the lower the formal MSME density (Figure 12). This is likely due to the fact that most MSMEs are more likely to operate in the informal/ Figure 12 MSME Density and Shadow Economy Figure 14 MSME Density and “Closing a Business” Recovery Rate Where the shadow economy is larger, there are fewer MSMEs participating in the formal economy. 100 150 IDN PRY 80 ISL CZE PRT MLT MUSGRC ECU BRN JAM MWI ITA 60 ESP NOR LUX KOR HUN SVN JPN CHL KEN HND FRAFIN BEL LTU CHE AUG POL ZAF SWL MEXIDN EST IDNSGPVNM NUL BGR NOD CAN EGY VAL SAI USR BWA SLV GBR JOR MAR ROMBRA IRL DEU MYS BGR USA YEM PAK HDP IDN KAZ ARE TTO CRI MDA SVKKWT ARG PMLRUS CHN RWA UGA LAO CMR OMN DOM BEA IDN IND CHA TUN 40 20 0 0 20 MSME Density MSME Density Where the recovery rate of investment in case of bankruptcy is lower, there are fewer formal MSMEs. 40 BOL PER UKR 60 80 Source: MSME Country Indicators, Buehn and Schneider (2009). Note: The figure uses data from 88 economies. The results of the regression are statistically significant at the 5 percent level. When controlling for GNI per capita, Atlas method (log), the results are not statistically significant at the 5 percent level. Included economies: (i) covered in both databases; (ii) with available GNI per capita, Atlas method. Where it is required to have more minimum capital to start a business, there are fewer MSMEs. IDN ECU ISL CZE PRT GRC MSME Density ITA ESP 60 HUNNOR LUX SVN BIH LTU PRY HND BELCHE POR SVE DNK TUR EST MEX AUT BGR NLD LVA 40 MARJOR TJK HRV DZA KAZ GTM UZB SVK PRY SRB PUL 20 GHA 0 0 PRY EZU CZE BLZ MUS MWI ITA NGA 20 40 ISL ESP HUN LUX SVN BOL CHL KENBIH ARM FRA HND ETU CHE POL IDN MNE URY EST THA IDN MEX IDN BCR IDN COL BWA LVA SAU ISR IDN SLV WBG JOR MAR BEL IDN IDN IDN DEU MYS BRA MKD BGD YEM IDN PAK IDN IDN GTM ARE TTO GLRIDN IDN KWT UZB SRA SVK RUS PHL JKR CHN UGA RWA LMO CMR BLR OMN LBNIDN KHM VENNOMKOZ MOD IDN SDN TZA 0 50 0 PRT JAM GRC 60 KOR NOR CYP JPN EIM HKO BEL SWEAUS DNK SGP AUT SZL NLD CAN GBR IRL USA 80 100 Source: MSME Country Indicators, Doing Business Index 2010. Note: The results of the regression are statistically significant at the 5 percent level, controlling for GNI per capita, Atlas method (log). The figure uses data from 113 economies. 12 unregistered sector in countries where the informal sector is large. Second, in economies where it is more costly to start or close a formal business, the density of formal MSMEs is lower. Specifically, the minimum capital for “Starting a Business” and the recovery rate for “Closing a Business” are strongly correlated with MSME density (Figures 13 and 14). In other words, in economies where more minimum capital is required to start a business and where it is harder to recover investments in case of closure of the business, formal MSME density is lower. Finally, corruption is negatively associated with MSME density, as evidenced by lower MSME density in countries where firms are more frequently asked to make informal payments (bribes) to government officials (Figure 15). Figure 13 MSME Density and Minimum Capital Requirement for “Starting a Business” 80 IDN Closing a Business: Recovery Rate (Cents on the dollar) Size of the Shadow Economy (percentage of GDP), 2005 100 100 KWT CHN UKR CMR KHM LBN 50 100 150 200 Starting a Business: Minimum Capital (precentage of the income per capita) Source: MSME Country Indicators, Doing Business Index 2010. Note: The results of the regression are statistically significant at the 10 percent level, controlling for GNI per capita, Atlas method (log). The figure uses data from 47 economies. 11 7 Notes Figure 15 MSME Density and Percentage of Firms Expected to Make Informal Payments Where there is more corruption, there are fewer MSMEs participating in the formal economy. 100 IDN PRY CZE PRT 80 MSME Density MUSMWI 60 ECU JAM GRC ESP HUN SVN BOL CHL ARM BIH LTU HND ZAF MNE POL URY EST MEX TUR VNM BGR OOL LVAGUY BWI SLV WBC MAI JOR PER TJK ROM IRL AZE BRA HRV PAK KAZ GTM CRI MDA SVK ARO SRB RUS PHL UKR RWA UGA BLR LAO TMPLBN CMR COMOMN GHA KGZ BFA MOZ IMO TZA 40 20 0 0 20 40 KEN BGD DZA UZB CHN KHM 60 80 Percentage of Firms Expected to Pay Informal Payment (to Get Things Done) Source: MSME Country Indicators, Enterprise Surveys. Note: Figure uses data from 70 economies. The results of the regression are statistically significant at the 5 percent level. When controlling for GNI per capita, Atlas method (log), the results are not statistically significant at the 5 percent level. References Buehn, Andreas and Schneider, Friedrich. 2009. “Shadow Economies and Corruption All Over the World: Revised Estimates for 120 Countries.” Economics: The Open-Access, Open-Assessment E-Journal, Vol. 1, 2007-2009 (Version 2). http://dx.doi. org/10.5018/economics-ejournal.ja.2007-9 Consultative Group to Assist the Poor. 2010. “Financial Access 2010.” http://www.cgap.org/p/site/c/template.rc/1.26.14234/ IFC and McKinsey & Company. 2010. “Two Trillion and Counting.” http://www.ifc.org/ifcext/media.nsf/Content IFC_McKinsey_SMEs IFC. 2009. “SME Banking Knowledge Guide.” http:// w w w. i f c. o r g / i f c e x t / g f m . n s f / A t t a c h m e n t s B y T i t l e / SMEBankingGuidebook/$FILE/SMEBankingGuide2009.pdf Klapper, Leora, Amit, Raphael, and Guillén, Mauro F. 2010. “Entrepreneurship and Firm Formation across Countries.” In Lerner, Josh, and Schoar, Antoinette, eds. International Differences in Entrepreneurship. National Bureau of Economic Research Conference Report. Chicago: University of Chicago Press Kushnir, Khrystyna. 2010. “How Do Economies Define MSMEs?” IFC and the World Bank. http://www.ifc.org/ msmecountryindicators Kushnir, Khrystyna. 2010. “Methodology Note on the MSME Country Indicators.” IFC and the World Bank. http://www.ifc. org/msmecountryindicators World Bank. 2009. “Doing Business 2010.” http://www.ifc.org/ msmecountryindicators Acknowledgments The authors would like to acknowledge the valuable contributions of Mohammad Amin, Roland Michelitsch, Peer Stein, and Hugh Stevenson. 8 1. For the legal definition of the MSMEs adopted by governments, please see the note: “How Do Economies Define MSMEs?” 2. This number was calculated using observations from 93 economies where the breakdown between micro, small, and medium enterprises was available. 3.Excluded economies: Algeria; Argentina; Armenia; Azerbaijan; Belarus; Belize; Bolivia; Burkina Faso; China; Ecuador; Ethiopia; Guyana; Hong Kong SAR, China; India; Indonesia; Korea, Rep.; Kuwait; Kyrgyz Republic; Malaysia; Mauritius; Nicaragua; Panama; Qatar; Singapore; Sri Lanka; Sudan; Thailand; United Arab Emirates and South Africa on the grounds that they apply an MSME definition that uses variables other than total employment or that their MSME definition is not available. 4. Kushnir, Khrystyna. 2010. “Methodology Note on the MSME Country Indicators.” IFC and the World Bank. http://www.ifc. org/msmecountryindicators 5. Excluded economies: Ethiopia; Puerto Rico; Sri Lanka; Nepal; Panama; Nicaragua; Sudan; Tunisia on the grounds that the data do not cover all sectors of the economy; Albania; Bahrain; Georgia on the grounds that data come from surveys; Belize; Brunei Darussaiam; Guatamala; Guyana; Iran, Islamic Rep. on the grounds that data beyond 2000 are not available. 6. Excluded economies: Ethiopia; Puerto Rico; Sri Lanka; Nepal; Panama; Nicaragua and Tunisia on the grounds that data do not cover all sectors of the economy; Albania; Bahrain and Georgia on the grounds that data come from surveys; Netherlands Antilles; American Samoa; Bermuda; Guam; Myanmar; Northern Mariana Islands; Qatar and the Virgin Islands (United States) on the grounds that the data on GNI per capita, using the Atlas method, are not available and Belize; Brunei Darussalam; Guatemala; Guyana and Iran, Islamic Rep. on the grounds that data beyond 2000 is not available. 7. Excluded economies: Ethiopia; Puerto Rico; Sri Lanka; Nepal; Panama; Nicaragua and Tunisia on the grounds that data do not cover all sectors of the economy; Albania; Bahrain and Georgia on the grounds that data come from surveys; Belize; Brunei Darussalam; Guatemala; Guyana and Iran, Islamic Rep. on the grounds that data beyond 2000 is not available. 8. This result is statistically significant at the 1 percent level. 9. Excluded economies: Ethiopia; Puerto Rico; Sri Lanka; Nepal; Panama; Nicaragua and Tunisia on the grounds that the data do not cover all sectors of the economy; Albania; Bahrain and Georgia on the grounds that the data come from surveys; Netherlands Antilles; American Samoa; Bermuda; Guam; Myanmar; Northern Mariana Islands; Qatar and Virgin Islands (United States) on the grounds that data on GNI per capita, Atlas method, are not available; Belize; Brunei Darussalam; Guatemala; Guyana and Iran, Islamic Rep. on the grounds that data beyond 2000 are not available; Timor-Leste; Burkina Faso; Dominican Republic; Sudan; Tanzania and Venezuela, RB on the grounds that data on employment by MSMEs are not available. 10.Excluded economies: Burkina Faso; Dominican Republic; Iran, Islamic Rep.; Sudan; Timor Leste; Tunisia; Tanzania and Venezuela, RB on the grounds that data are not available; Belize; Brunei Darussalam; Guatemala and Guyana on the grounds that data after 2000 are not available; Bolivia; Botswana; Cameroon and Trinidad and Tobago on the gounds that data cover enterprises in the private sector only; Canada and Tajikistan on the grounds that data cover enterprises with no employees; Sri Lanka and Mauritius on the grounds that data do not cover all sizes of MSMEs; the West Bank and Gaza on the grounds that data include governmental and non-governmental enterprises; Montenegro on the grounds that there are no data on total employment; Albania; Bahrain and Georgia on the grounds that data come from surveys; Ethiopia; Nepal; Nicaragua; Panama and Puerto Rico on the grounds that data do not cover all sectors of the economy. 11.Excluded economies: Ethiopia; Puerto Rico; Sri Lanka; Nepal; Panama; Nicaragua and Tunisia on the grounds that data do not cover all sectors of the economy; Albania; Bahrain and Georgia on the grounds that data come from surveys; Netherlands Antilles; Bermuda; Guam; Malta; Myanmar; Northern Mariana Islands and Virgin Islands (United States) on the grounds that they are not covered by the Doing Business Index data; Qatar and American Samoa on the basis that the data on GNI per capita, Atlas method are not available. In addition, countries with minimum capital of less than 5 percent of GNI per capita and those with minimum capital above 200 percent of GNI per capita were also excluded to minimize the possibility of results being driven by outliers. 12.Excluded economies: Ethiopia; Puerto Rico; Sri Lanka; Nepal; Panama; Nicaragua and Tunisia on the grounds that data do not cover all sectors of the economy; Albania; Bahrain and Georgia on the grounds that data come from surveys; Netherlands Antilles; Bermuda; Guam; Malta; Myanmar; Northern Mariana Islands and Virgin Islands (United States) on the grounds that they are not covered by the Doing Business Index data; Qatar and American Samoa on the basis that the data on GNI per capita, Atlas method are not available. MSME Country Indicators is a joint work of Access to Finance, Global Indicators and Analysis, and Sustainable Business Advisory. Visit MSME Country Indicators at http://www.ifc.org/msmecountryindicators. This publication carries the names of the authors and should be cited accordingly. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this note are entirely those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/World Bank and its affiliated organizations, or those of the Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. 9