Getting Organizational Change Right

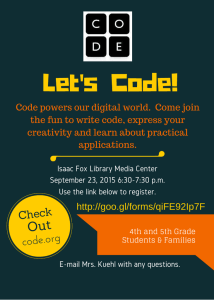

advertisement