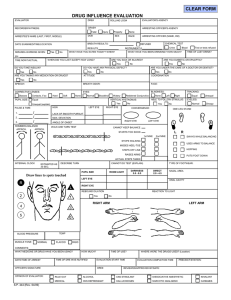

The Drug Evaluation and Classification (DEC)

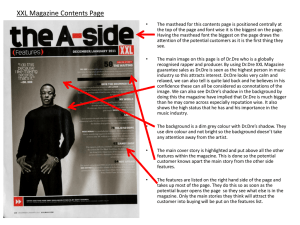

advertisement