Reduce, Reuse, Recycle | US EPA - US Environmental Protection

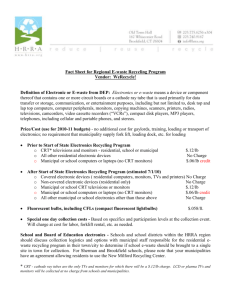

advertisement