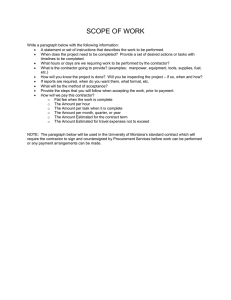

Contractor quality control: A method of construction

advertisement