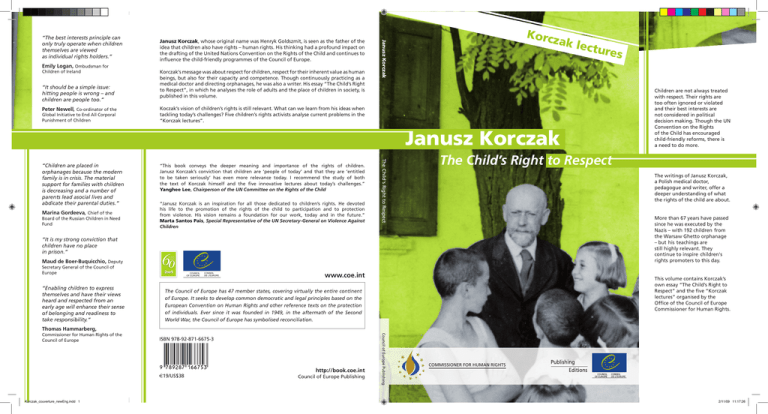

Janusz Korczak, the Child`s Right to Respect

advertisement