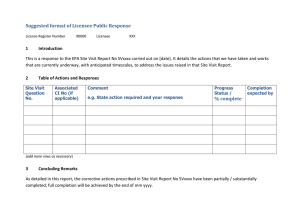

Successful Technology Licensing

advertisement