Sirius Mistake - Digital Commons @ American University

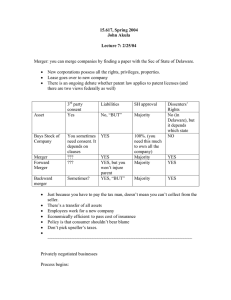

advertisement