1) CNRU, CFIN, Dept. of Clinical Medicine, Aarhus University. 2

advertisement

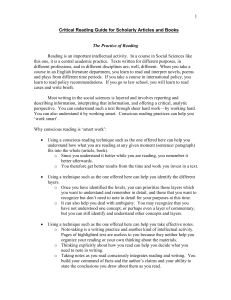

What do we mean when we ask “Do we have free will”? Mikkel C. Vinding1 & Morten Overgaard1,2 1) CNRU, CFIN, Dept. of Clinical Medicine, Aarhus University. 2) CCN, Dept. of Communications and Psychology, Aalborg University. Abstract Action There are many, sometimes conflicting, definitions of free will. For a scientific approach to succeed it should not begin by selecting one such definition, but start with the definitions, incongruent or not, and specify possible empirical ways to address these, and the epistemological and methodological obstacles. Will is taken as conscious experience related to action generation. This gives rise to the same problems and questions as investigating the mind-brain problem: How will relate to neural states? The first step is to investigate phenomenological experiences related to action generation, using first-person perspective methodology; then relate these to the physiological mechanisms in action generation. To answer whether will is free demands a different approach. Freedom can be defined in several ways, and each definition has its own metaphysical assumptions. Freedom defined as either ‘genuine freedom’ in the metaphysical sense, or as autonomy is considered, including how the level of analysis (psychological, fundamental, etc.) affects the scientific answers we can ask. Together this leads to the problem of mental causation. Including the previous questions, this goes beyond asking whether mental states have causal properties or are determined. Instead we should view action generation as function of a complex system, involving many conscious and unconscious processes. focus should be on describing causal pathways in neural networks and relate different experiences of will to these. For specific actions we can build model of how will contribute to action, and, depending on the definition of freedom we choose, state whether it was a “free will-action”. There are many forms of action. We cannot assume one process behind action generation. It is likely that we need several models for different types of actions. A scientific approach to free will (a) The criterion for something to qualify as “free will” vary, depending on which philosophical position you confront. With free will we have a concept that denotes different phenomena (even if only hypothetical) and the concept suffers from being overdefined, thus losing its meaning outside the specific position. (b) Much of the free will debate have been focused on freedom and causality, somewhat neglecting giving a proper definition of what will – as conscious mental states – really is about. Previously will has been used synonymously with; action initiation, Intention, decision-making, Executive control and Sense of agency. Though none of these seem to entirely capture what will itself means. Given the various mental states will embrace, conscious will should not be approached as a single mental state Action generation is a function of a complex system, involving many processes. The performance of actions demands an integration of relevant information for the action, such as senso-motoric for body control, visual information, semantic information about context, etc. What we are looking at are complex systems, even without differentiating between conscious and unconscious processes. Will is a category of mental states about or in relation to action and action What are the mechanisms behind action generation? The questions to answer is: Which processes and what information is necessary for action? How much does the processes and information contribute? What is the causal relation between the processes? Scientific study hereof should aim at describing causal pathways in neural networks (which networks? Integration of information? How: Parallel streams, specific linear series etc.?). Answering the questions above, we can begin to make cognitive and neural models over the time course of the physical states involved in generating actions. The next to ask is: How does conscious will relate to neural processes of action generation? Whether this question is empirical or metaphysical is a matter of debate. Basically the mind-body problem specifically for conscious will. Same methodology as research on other domains of consciousness research. The relevant question is: Which aspects of action generation is automatic and how much is conscious? Process might not always be unconscious, but only consciously accessible sometimes. Different actions might have different involvement of conscious will? These are questions that needs a posteriori answers – they are empirical questions, that needs to be addressed. The problem is giving an a priori definition of free will that will work as basis for scientific studies. As a consequence: Person A concluding that free will has been disproved by the new empirical insight, rightfully according to A’s initial definition of free will, is challenged by person B claiming that free will has not been disproved, also rightfully according to B’s definition of free will. Since both define “free will” differently, they end up having a disagreement of whether free will exists or not. The form of this disagreement appears to be a disagreement about ontology, when it in fact is a disagreement about a priori definition. Definitions of free will can be formulated as factual statements. These can be true or false (in scientific terms; plausible or unlikely). To have a successful scientific approach to free will we should not a priori settle on specific definitions of free will, but formulate existing assumptions as empirical questions (when possible). This will go beyond asking “Do we have free will?” as a simple yes or no question. Instead of studying free will as an object, it is best viewed as a collection of scientific questions about conscious will and causal mechanisms in action generation. The subject for a science of free will is the role of conscious will in the causal mechanisms associated with action and action generation. Mental causation (c) Addressing mental causation, we likely have several conscious and unconscious process alike that are necessary for action. To address mental causation is not to ask: Do mental properties (M) cause action (A)? (M → A). It cannot assume that neither conscious will nor mechanisms in action generation are singular processes. Different aspects of conscious will might have different causal properties (e.g. that prior intention a causal facilitators of action, whereas the sense of agency reflects action feedback monitoring). This should be taken into account when approaching mental causation – not just empirically, but also in deductive arguments. Instead of treating conscious will (M) as a unified state, we should identify the different aspects (M1, M2, …, Mn) of conscious will, over time. The same apply to the cognitive and neural mechanisms (P) in action generation – we should identify the different mechanisms (P1, P2, …, Px) - investigate how they are causally connected – and then relate the different aspects of conscious will to activation of the causal system. The scientific approach to free will should relate differences in specific subjective reports as a function of network activation. And then ask the question: What are the causal properties of various content of conscious will? Cognitive Neuroscience Research Unit Aarhus University / Aarhus University Hospital www.cnru.dk Follow CNRU: www.facebook.com/CognitiveNeuroscienceResearchUnit Too much text? Read this poster online. Conscious will (b) To avoid confusing the plurality of what phenomenological will, and the singular form of the word will - action consciousness might be a better term. No metaphysical assumptions are made about the nature of conscious will. The first answer we need to investigate is: What is the phenomenological content of will? There is a need for description and classification of the phenomenology related to action. How are the various experiences related? Is there an overlap or might they be different stages in the same global process? Is there a necessary time-course or progression in the experiences? These are empirical questions dependent on first-person or qualitative methodology. Contemporary scientific approaches to free will relies to a great extend on indirect measures, rather than subjective reports. In order to develop a scientific approach to free will there is a need for more phenomenologically informed measurements. The scientific study of conscious will falls within the already established field of consciousness research. The “usual problems” regarding mind-body relation, epistemology of 1st person perspective etc., apply here as well. There here however some conceptual and methodological concerns that are salient when investigating conscious will, compared to other aspects of consciousness. The possibility of of automated or unconscious actions and action generation is a confounding factor when looking for correlates of conscious will. Much of this information necessary for action generation is (probably) unconscious and/or inaccessible by direct report. To scientifically investigating the causal role of conscious will it is important to consider the distinction between unconscious processes, and conscious content not available for post hoc introspective reports. Introspection on content of conscious will is perception of internal events. When using introspective reports, there are not direct “objective” measures for comparison to – as there are, e.g., in research on visual consciousness, where introspection is about perception of external objects. This emphasises the need for development of adequate tools for “measuring” conscious will. Asking whether A is free is asking whether a specific causal relation (or lack thereof) is true in the relation between A and something else B: “is A free from B?”. What the “specific casual relation” is, and how to determine if it is a true condition, depends on the meaning attributed to freedom. Genuine freedom A is free from B, if there is no relation whatsoever between A and B. To say that A is genuine free from B means that if B, it is random if A. There is no formal language to express this relation; it is indeterminable. This is the definition often found in the metaphysical discussion of determinism. It is however not a definition constrained to metaphysical discussions. Autonomy A is free from B, if the behaviour of A is a result of A in itself rather than a consequence of B. Whatever behaviour we observe in A is guided by self-steering processes in A, and not B. Autonomy therefore requires an instinctive feature in A that can be the cause of A's behaviour. A must therefore in itself be dependent on other causal relations, or it would have to be a causa sui. Therefore autonomy is a feature of a causal system. Note that autonomy does not exclude that there is a relation between A and B - only that the relation is not so that B is not the sole cause of A. There is a clear logical criterion for A being genuinely free from B: True or false. To determine whether A is autonomous from B, is not as simple as that. Using freedom as autonomy, one is obliged to further develop the terminology, both qualitatively and quantitatively. How to define the parameters to determine autonomy? Whether A is free from B (using either definition above) is an empirical question. It does demand that we a priori specify what A and B denote. For free will A denotes conscious will, but B can denote many different things. Examples: Genuine freedom Autonomy Fundamental (Universal) If conscious will is free, it has to work (Not possible. Autonomy is a feature Metaphysical level – determinism. outside the laws of physics. of a causal system). Psychological level Conscious will is not caused by prior unconscious neural or cognitive mechanisms. Conscious will is the single cause of action. Conscious will can be dependent on unconscious processes. Free as long as conscious will is significant contributor to action. The assessment of freedom is then no longer a question of either/or, but is dependent on the specific processes involved. Causal relation of neural and cognitive processes or conscious and unconscious processes. Actions performed by individuals are Distinguishing individuals from uninfluenced by social factors. E.g. a traditional Kantian agent who, other individuals, groups, culture, society and other social unaffected by context, makes rational choices that guide action. factors. Social level Individuals could be acting under social influence, as long as they are acting on behalf of their own intentions and thoughts, they are free. Freedom and personal responsibility (e) What definition of freedom should we use? This question can only be answered if we consider: Why do we want to know whether an action is a free will action? Free will is taken as a prerequisite for personal responsibility. What definition of freedom we use is dependent on the conditions under which we want to address personal responsibility. To talk about responsibility over actions implies that we can condemn or sanction actions. None of the questions elsewhere on this poster imply that we could, or should, hold people responsible for their actions. To ascribe personal responsibility makes sense only from a normative perspective, in which there are prescriptions for how action ought to be. Though the free will debate takes form as a discussion of ontology question, it has a strong but hidden normative element. This becomes clear when the question of defining freedom, is rephrased into: How ought we define free will? Normative principles It is likely that we need several models for different types of actions or several models for different kinds of implementation of intention, decision strategies, etc. – how this best works has to be determined by the a posteriori results. For specific actions we can then build models of how and which conscious experience that contribute to action. Freedom (d) Ethics Normative statements Assessment of personal responsibility Factual statements Facts - “How thins are” “Universal” Context specific When we want to determine whether an action is a “free will action”, we need to consult not just factual statement, but also normative statements. Normative statements are about how one ought to act in relation to a given object or given situation. They are derived from global normative principle (e.g. maximise happiness, what is good, etc.). A normative statement is dependent on facts about objects or situations. A scientific approach to free will provide the factual statements, but have to be aware of the normative element - as well as ethics has to take the scientific approach into account as well, when issuing normative statements. This emphasise the need for a science of free will.