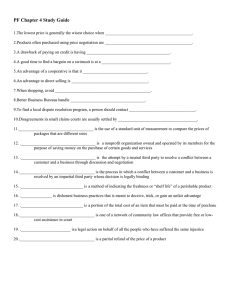

The Need for the Development ... the NZDipBus. Author:

advertisement

The Need for the Development of Negotiation and Dispute Resolution Skills in the NZDipBus. Author: John F Cuttance, Tutor, Whitireia Community Polytechnic. Introduction: This paper is about conflict, negotiation, and conflict resolution and why the teaching of the skills for negotiation and alternative dispute resolution should be taught to business students. Imagine the situation that Dr Suess, described in The Sneetches. He portrays two stubborn Zaks who refuse to alter the path’s they are walking as they come face to face. As they stand fixed, nose-to-nose, Dr Suess describes their situation: “Not an inch to the West, not an inch to the East. I’ll stay here not budging. I can, I will. If it makes me and you and the whole world stand still.-----Of course the world did not stand still --------the whole world grew and left them there standing unbudged in their tracks”. The Zak’s are locked in classic conflict, head to head with no ability or room to move. If a person lacks effective negotiation skills he or she will be like the Zak’s, stuck in the same spot in a world that is moving around them. They will avoid what faces them because they are unable to accept and deal in a positive or productive manner with the conflicts that will confront them on a daily basis. The failure to effectively negotiate may result in the person being seen as intransigent, stubborn, uncooperative, and autocratic or as a bully. A more palatable view of conflict is expressed by Burton (1972): Conflict is like sex. It is an important and persuasive aspect of life. It should be enjoyed and should occur with a reasonable degree of frequency. After conflict is over people should feel better as a result”. Of course most of us would prefer to experience conflict as portrayed by Burton than that faced by the Zak’s, But the reality is that many people don’t enjoy conflict because they have failed to develop and do not have the skills necessary to negotiate in a manner that allows them to turn the negative aspects of conflict into positive gains. Negotiation: As a society we have ingrained into our minds that to negotiate is to show weakness. In the old Western movies this was the ‘shoot first, ask questions later’ stance. Being staunch is seen as strength. Daily we see newspaper reports of the disastrous consequences of people’s inability to deal with conflict. In the business world we recently experienced two multinational corporations that failed to successful negotiate the future development of New Zealand’s largest forest assets and on the international scene the world looks on in horror at the consequences of the Israel / Palestinian conflict. 2 Tillet (1999) sees conflict as an inevitable and pervasive aspect of human life. “Conflict is sometimes physically violent, but more often not. Much of it exists within the mind and is expressed in words; some of it, however, is expressed with fists, guns, or bombs. Conflict can occur over a suburban fence or in a family living room, on a battlefield or in a courtroom, in a workplace or a parliament, on a sports field, or in a street. Conflict can erupt suddenly, or it can smoulder for years or even for generations. It can focus on trivia, or concern the future of life on earth” Conflict is popularly equated with fighting and is generally seen as destructive, unpleasant, and undesirable. It is usually suppressed, avoided, concealed, or fought over. It commonly provokes negative responses, which can have detrimental effects on the individual, on relationships, and on groups. It can break down communication, destroy relationships and lives, increase problems, and erect barriers.” Conflict is not all bad if it is dealt with in a positive and constructive manner. Out of conflict can develop new ideas, better understanding, better personal or business relationships, individual and corporate growth. Only through effective and positive negotiation can we move forward. Of course, people will often say that that you don’t need to learn to negotiate, it comes to us as second nature. Infants soon discover that they can deal with conflict, usually over the acquisition of ‘resources’, and get more of what they want by developing some raw negotiating skills. However, they quickly discover that what they can do, or get away with, when playing with their playmates will not achieve the same results when they face their older and generally larger siblings and parents. They soon learn that although ‘might is right’ is okay to use with their playmates, it is not much use with those who are bigger, stronger and more powerful. A natural reaction is then to try to develop their strengths so that they become the ‘mighty’. However, as they grow older they soon learn that there is always someone “mightier’, be they people who are physically larger and therefore more threatening, or of greater status and authority, such as the ‘State”, with its powers of laws and policemen, or the power of the multi-national corporation with it’s international financial strength. Luckily, infants have short memories and the ability to use the ‘might is right’ style of negotiation in the play-pen does not usually lead to a permanent breakdown in the personal relationships. In contrast, in the real life of the adult world and especially in the world of business long term relationships are essential for survival and success. Such philosophies as ‘might is right’ quickly destroy relationships and often promote counter attack. From my days as a teenager, or was it earlier, I recall the advertisements on the back of the ‘Tarzan” comic books advertising the body-building courses that would guarantee the puny me that if I bought the advertised product I would quickly develop in to that Mr Universe guy and that nobody would dare kick sand in my face again. I would have no problems negotiating for the desired prize, the Marilyn Munro look alike. Unfortunately life is not so simple and most of us realise we have to develop much more sophisticated skills in order to deal with conflict. Even with the best use of our 3 ‘innate’ skills we soon find that there are many conflict situations were we are totally inadequate. I am sure we have all experienced being ‘done-over’ or ‘ripped-off’ as a result of our inadequate negotiation skills? The art of negotiation is to use developed skills in order to avoid unwarranted compromise or to buckle to pressure. To be able to negotiate in the face of adversity is not a sign of weakness. Negotiation is derived from the Latin word ‘negotium’ meaning business and it refers to the activity of conferring or bargaining with a view to reaching agreement. It is a creative process of give and take, a trading of variables over which the parties exercise discretion, leading to an outcome which acknowledges the differing perspectives of those involved.” (Spiller, Ed. 1999). Negotiation is a part of everyday life, both in our personal affairs, and especially in the business environment. It is about issues of power, resources and identity. The ability to ‘negotiate’ may mean the difference between business success and failure. Conflict related to the trading, transfer, conversion and distribution of the factors of production is a natural element of business and commerce, whether those resources be financial, physical or human. Success, failure, growth, survival, and respect will all depend on the business manager’s ability to negotiate. In the Court of Appeal, Hardie Boys J. in Capital Coast Health Ltd v NZ Medical Laboratory Workers Union Inc [1955] 2 ERNZ 305 stated: Negotiations are …… a process of mutual discussion and bargaining, involving putting forward and debating proposal and counter-proposal, conceding, persuading, threatening, all with the objective of reaching what will probably be a compromise that the parties are able to accept and live with.” The need for negotiation skills in business is well recognised. In 1991 a Commission report to the US Secretary of Labour, prioritised the most important communication skills that workers would require in the new millennium. Among the ten most important skills identified were the need to: Negotiate with others to solve problems or reach decisions, and Develop strategies for accomplishing team objectives and resolving group conflict. (Spangle and Moorhead 1997). In the New Zealand context Spiller (1999) states that; “From the perspective of a business manager …, negotiation is one of the primary skills that he or she must develop. Whether the manager or lawyer is involved in negotiation to settle threatened litigation or in complex join-venture arrangements, negotiation is one of his or her most important functions.” One of the most popular books on negotiation, Getting to Yes, (Fisher and Ury 1981) started as the question “What is the best way for people to deal with their differences?” In answer to this question the authors introduced a number of concepts such as the avoidance of arguing over ‘positions’, separation of the people from the 4 problem, focusing on interests and not positions, and of course, the achievement of the ‘win – win’ outcome. Traditionally we are warriors rather than negotiators. We will use our strengths, be they physical or authoritative in an endeavour to achieve what we perceive will be the best outcome for ourselves. This will be a ‘win–lose’ outcome. After all, we grow up in a world of competition. Through sport and competition we have ingrained into our minds from the earliest age that winning is all-important. We are told that there are no prizes for coming second. So why should we compromise? Why should we not endeavourer to win at all costs? Why should we be concerned for the outcome of the other party? Our legal system has been based upon an adversarial win-lose approach to the resolution of conflict. If that is to be the final arbiter why should we not negotiate with the sole purpose of winning? An almost inevitable outcome of win-lose negotiations or litigation is the destruction of relationships. Although relationships may have taken years to build at substantial cost they can be instantly destroyed by unmanaged conflict. Trust flies out the window and the parties become stubborn Zak’s. The art and skill of effective negotiation is to take a different approach with the underlying principals of fairness and relationship building. Deutsche (1987) proposes that conflict can be either constructive or destructive. He suggests that resolving conflict constructively always requires a cooperative approach to the task, whereas destructive conflict features attempts to conquer the other side. (Sligo 1990). When we view negotiation from both from the win-lose perspective and the Fisher and Ury win-win approach we see that negotiation engages two opposing and interconnected elements, ‘competition’ and ‘cooperation’. These two elements create a dilemma for the negotiator, the inescapable tension between cooperation in order to create mutual benefit and competition with the expectation of individual success. There is a growing body of opinion that to negotiate with the sole purpose of achieving individual success is unlikely to produce the best outcomes. No matter what your perceived strengths, to use them to take all the spoils of conflict may not produce for you the best solution. In dealing with the tension between cooperation and competition it is said that the effective negotiator must be as much concerned with finding an outcome that the other party can agree with as he or she is with the promotion or protection of a preferred position. (Spiller, Ed 1999). Although many people will recognise the importance of negotiation as a mechanism for making decisions, solving problems and managing conflict they will still hold back from any attempt to learn the art of negotiation. People frequently find the prospect of negotiation uncomfortable and distasteful. Conflict may make them feel very insecure. However, the fact is we all have to negotiate to live. Everyday we find ourselves in situations where we must coordinate our preferences with those of others, influence other people to our way of thinking, or resolve conflicts. Many people, because of their fears, make every effort to practice avoidance and they put their efforts into steering clear of any sign of argument, disagreement or conflict. 5 Unfortunately, in business and in the work place it is almost impossible to survive on the basis of avoidance. (Lewicki, Sanders and Minton 1999) Although the basis of most negotiation is some form of conflict it does not have to be a hostile, bloody or psychologically intimidating process to be successful. In fact, if it is any of these it is unlikely to produce a successful or acceptable outcome. To be a successful negotiator one does not need to be verbally glib, particularly articulate, very persuasive, a fast and smooth talker or a ‘con’ artist. Lewicki, Sanders and Minton (1999) found that; “The skills needed to be an effective negotiator can be taught and learned. Negotiation is a complex human activity. It involves a dynamic interpersonal process. It requires an intellectual ability to understand the key factors that tend to shape and characterise different negotiations. It requires skills, both behavioural and analytical, to diagnose negotiation problems and select the correct strategies and approaches. It also requires an understanding of one’s own personality and one’s system of personal ethics and values, because these will affect how we perceive situations and how we determine the appropriate strategy and tactics. Finally, negotiation is a learnable process. We do not have to be born with the skill. Most of us can improve with a few lessons, a bit of coaching and some tips on how to do it better.” Tillett (1999) says that conflict resolution essentially involves a set of practical skills which are not esoteric or complex. They are basic intellectual and interpersonal skills that everyone possesses, but that are largely under developed and unapplied. Included in the skills he identifies are those of analysis, motivation, thinking, empathy and selfdisclosure. ADR and Mediation: Along with the development of the cooperative ‘win-win’ approach to negotiation has been the recognition of the need to find an alternative to the traditional litigation approach for the resolution of intractable conflicts. Consequently the last decade or so has seen the rise of ADR, Alternative Dispute Resolution. Although ADR may cover a number of different systems of dispute resolution the most frequently used are Mediation and Arbitration. Arbitration has existed in our legal system for nearly 100 years through the Arbitration Act 1908. However, because of its prescriptive and restrictive approach arbitration was generally limited to the fields of property lease and building disputes. The Arbitration Act 1996 has given new life to the use of arbitration as a tool for conflict resolution and we have recently experienced it’s successful application in the resolution of the long running secondary teachers employment dispute. Mediation is rapidly gained acceptance as a useful form of ADR. The introduction of the Employment Contracts Act 1991 saw a major leap in the understanding and use of the mediation process. The Employment Relations Act 2000 has taken mediation to an even higher plane of use and acceptance. 6 Although the legal profession has been slow to accept mediation as a form of dispute resolution legal documents now frequently make provision for the reference of disputes to mediation as a first step in the conflict resolution process. A number of statutory provisions now give legal recognition to mediation procedures. Green (2002) refers to Mediation as an extension of the negotiation process. It is part of the negotiation continuum where an impartial mediator helps the parties in dealing with their conflict by facilitating continued negotiation in a managed way. Fogleberg and Taylor (1984) defined mediation as the bringing together parties in conflict with a neutral person or persons whose function is to assist the parties to resolve the dispute through the systematic isolation of issues and development of settlement options to achieve consensual accommodation of needs. Conclusion: Employers and the business community value the NZDipBus qualification for the practical and usable skills it provides to graduates. In recent discussion with and experienced recruitment agent she commented that the NZDipBus qualification equated with business experience as opposed to being simply a qualification. In order to maintain the relevance of the NZDipBus as a mainstream business qualification we must not only meet the demands of the business market, but we must also be innovative . With the exception of 235 Employment Relations, where the statutory mediation process forms part of the teaching of the legal provisions relating to employment disputes, and a single reference to negotiation in the 140 Business Communication paper I have been unable to find any paper in the Diploma course that provides for the teaching of negotiation or dispute resolution skills. I am aware that a number of Tutors, including myself, do teach some elements of ADR in the 110 Introduction to Commercial Law paper as the Special Topic. No doubt, negotiation will form part of the teaching in other papers but it certainly does not form a significant part of any Diploma course prescription. I believe there is a need to address this omission in our course subjects if the Diploma is to remain relevant to modern business requirements. As Lewicki, Sanders and Minton (1999) said, negotiation is a learnable process. However the NZDipBus does not treat it as such. It is my argument that the art, process and practice of negotiation are too important to leave to chance. Negotiation and conflict resolution were identified by the 1991 US Secretary of Labour’s Commission as among the most important communication skills required for workers in the new millennium. It is often said we in New Zealand are a decade behind America in many areas of our teaching. Well, the decade has past since the need for development of negotiation and conflict resolution skills was identified so it must be time for the introduction of the teaching of negotiation and conflict resolution skills as a main stream Diploma subject. 7 References: Burton, John W. (1972) World Society; London; Cambridge University Press. Cited in Sligo, (1990). Deutsche, Morton. (1987) A Theoretical Perspective on Conflict an Conflict Resolution, in Conflict Management and Problem Solving: Interpersonal to International Applications, Dennis J.D. Sandole and Ingrid Sandole-Staroste, Eds., London: Francis Pinter. Cited in Sligo, (1990). Fisher, Roger & Ury, William, (1990) Getting to Yes, London: Hutchinson Business Press. Fogleberg, J., & Taylor, A., (1984) Mediation: A Comprehensive Guide to Resolving Conflict Without Litigation, San Franscisco, Jossey Bass. Cited in Green, (2002). Green, Phillip D., (2002) Employment Dispute Resolution, Wellington: LexisNexis Butterworths. Lewicki, Roy, J., Saunders, David R., & Minton, John W., (1999) Negotiation (3rd Ed.). Boston: Irwin McGraw-Hill. Sligo, Frank. (1990) Conflict Management: A New Zealand handbook, Wellington: GP Books. Spangle, Michael & Moorhead, Jacqueline, Interpersonal Communication, Iowa USA, Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company. Spiller, Peter, (Ed.). (1999) Dispute Resolution in New Zealand, Auckland: Oxford University Press. Tillett, George., (1999) Resolving Conflict; A practical approach, (2nd Ed.). Melbourne: Oxford University Press,