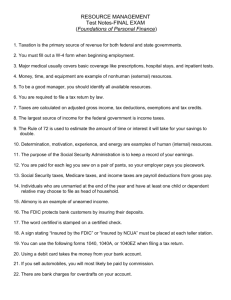

When Good Intentions are Not Enough women’s economic empowerment

advertisement

When Good Intentions are Not Enough NGO - private sector partnerships and state policy for women’s economic empowerment Key conference questions • What is the most effective balance between the state and the private sector in achieving sustainable national development? What are the roles that state and private sector might play in promoting development? • What are the most effective policies for assisting particularly vulnerable groups to better integrate into national economic processes? Key points • Economic processes and institutions are not value neutral entities. They are shaped by the same biases, including gender biases, as the cultures that produced them. • The most common development solutions towards gender equality in economic growth focus primarily on changing women and/or their communities. Interventions that call on other actors, such as the private sector, to develop are needed if development interventions are to be accurately targeted and if their results are to be sustained. • NGOs, the private sector and governments already possess good examples of policy, programs or practices to solutions to make changes to the market, but they need to be more widely implemented. Case studies Zimbabwe Indonesia • Micro- and small agrodealer enterprises in Masvingo • 5 year project beginning in 2007 • Goal: strengthen market linkages in agricultural supply chains • Micro- and small seaweed and fish processing enterprises in South Sulawesi • 4 year project (approval pending) • Goal: reduce gender inequalities in small business knowledge and service provision July 27, 2016 Loan sizes follow gender bias, not credit worthiness • Maximum loan provided to women was USD $8,000 and to men was USD $10,000. • But median amount in the $1,000 to $2,500 range for women and $1,500 to $4,000 for men. • The amount approved for men increased more quickly. • The FI says that men are riskier, but they loan them more anyways. • The FI continues an assumption that men do big business as the head of the family and women to small business to supplement household income. Collateral continues to restrict women’s business expansion • The FIs will only approve soft loans up to $2,000 and $5,000 respectively. Collateral must be 200% the value of the loan. • Hard collateral is out of the reach of most Zimbabwean women. • This effectively shuts women out of larger loans and decreases their ability to compete through bulk purchasing. Women subsidize FIs and the NGO reinforces this • When men’s businesses fail, the NGO signs loan responsibility over to female beneficiaries. • It is easier to contact women to ensure they pay their loans back. So who is working for whom • It is to the bank’s advantage to have a large number of here? clients all paying back a known amount of interest reliably. • When women regularly pay interest on medium-sized loans, or when they turn men’s businesses around, they ensure predictable cash flow for the FIs and subsidize men’s risky behaviour. Solutions for NGOs and the private sector • NGOs: Ensure your business planning and marketing homework is done before project implementation. • Complete gender sensitive value chain analysis and marketing studies before engaging women in business. • Include a “do no harm” strategy to minimize known negative impacts of promoting female entrepreneurs. • Only partner with private sector actors who are willing to change their practices or products. • Financial institutions: You’re a product of culture, and it really does affect the bottom line. • Examine the effects of social biases on business strategies (and profits). Use sex-disaggregated financial data to show how female and male clients really behave. • Hire and promote women to loan officer positions. Train all officers to apply banking rules uniformly and to work with female as well as male clients. • Create incentives for increasing the variety of products women can access and for promoting men to take on only sound risk. Cracks in the foundation of Indonesia’s economic growth large, medium and small L/M enterprises: enterprises almost all owned 1% of allbyofmen Indonesia's enterprises S enterprises: 32% owned by women most of the 32% of women are here micro-enterprises: women more likelymicro-enterprises labourers, men more likely owners 99% of enterprises in Indonesia women almost no all ownership of collateral, low access to appropriate financing, less access to extension, The majority of women's businesses fall intoweak this business management and product quality knowledge, category (no formal data with an exact percentage weaker linkages to markets, exists). men more membership in business collectives, more access to government support schemes biases in financial, business service provision and regulations Gender inequalities lead to low product quality and business profits • In the seaweed sector in South Sulawesi, women are responsible for 90% of labour but receive only about 10% of related extension. Financial products are not suitable to poor businesswomen • IWAPI negotiated two different types of products with a national FI. • The FI cancelled one product, saying that interest earnings were not sufficient to warrant administration costs. • In the case of the other product, businesswomen who took advantage of the supposedly lower borrowing rates on a group loan ended up paying interest on the total amount of the loan rather than just their portion of it. Policies are in place, but not enacted • Business registration procedures are the same for women and men on the books, but officers will often require supplementary documentation or men’s signatures from women. • IWAPI and others note outright discrimination such as women being told that they have been refused their loans because lending to women will increase the divorce rate. • It is custom that only men sign property deeds, even though Indonesian law provides for two signatures. Solutions for government and the private sector • Government: • Enforce property registration laws. Develop legislation to register informal businesses as property. • Ensure extension agents are trained to meet the needs of female clients and that women are included in value chain development work and schemes supported by MOA . • Strengthen the national women’s ministry to work with the ministry of cooperatives on the breadth, depth and quality of services. This includes training for line agents and loan officers. • Continue to develop one-stop-shops for business registration. • Financial institutions: • Create a business model in which a percentage of financial products are of a type that is more appropriate for poor women. Intentionally plan this in order to mitigate risk. • Train business registration officers and provide incentives to those who apply the same standards of service to women and men. In conclusion • There are limits to the extent to which subalterns are able to engage in their own empowerment projects without equal change from those who hold more formal power. • Development efforts in gender equality in economic growth are reaching those limits. • What creative processes and packages can be used with FIs, male intermediaries and larger scale businessmen, community leaders, or government line agents? • How does government hold itself and citizens accountable for change? Thank you Questions? Comments? For more information, contact margaret.capelazo@care.ca I’m a human being, not a market! But we’re still waiting for you to recognize our rights, I stopped waiting and started acting years ago! and for property ownership,… and equal salaries,… and our share in valued markets,… and for men to take on reproductive work.