23460 >> Amy Draves: Good afternoon. My name is... introduce and welcome George Anders, who is joining us as...

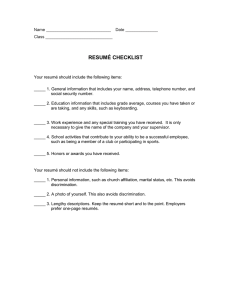

advertisement

23460 >> Amy Draves: Good afternoon. My name is Amy Draves, and I'm here to introduce and welcome George Anders, who is joining us as part of the Microsoft Research Visiting Speakers Series. George is here today to discuss his book: "The Rare Find: Spotting Exceptional Talent Before Everyone Else." He's been visiting everyone from soldiers to surgeons, learning about how great American organizations pick talent. Anyone at Microsoft who has been an interviewer knows that distinguishing between a good interviewee and a great hire can be challenging. The good news is that this ability can be honed. George Anders is one of the founding writers at Bloomberg View, and while at the Wall Street Journal he won a Pulitzer in 1997. He's also the author of "Merchants of Debt: Health Against Wealth and Perfect Enough." He's been using Microsoft products since the days of DOS. Please join me in welcoming him to Microsoft. [applause] >> George Anders: Thanks very much for coming. And thanks for giving me the chance to visit Microsoft. I used to come up here in 1993. My wife was very briefly part of a research project that Nathan Mierfold was leading, and I think anyone who spent a few months in the company of Nathan at the very least has a whole lot of stories to tell. And we've got a few. What I wanted to do today was tell you a little bit about how I came to write this book, what I learned in the course of research and then some things that might be applicable to the Microsoft community. This is a book that probably got started a dozen years ago. I was writing for the Wall Street Journal then. I was covering the dotcom economy and venture capital. And I had wanted to embed myself inside a venture firm to see how in the world they picked a deal. Amazon had gone public at the time. It was a fabulous success. It was at that time incurring big losses but had a gigantic stock market value. So it had easily a dozen, two dozen firms on Sandhill Road going how do we find the next Amazon. And I got one to take me inside as they heard their auditions. They let me listen to a half dozen different pitches. The one I quickly glommed on to was something called living.com, and it was going to sell furniture online. Now with the benefit of hindsight, furniture is probably a uniquely bad product to sell online. The shipment is difficult. You want to sit on the sofa. Return policy is very problematic. And there isn't a standard SKU. When you buy a song, when you buy a book, when you buy a lot of things, that's exactly what you're buying. Furniture is always customized and the delivery times are huge. So we can go on and on about why the idea wasn't going to work. But this was 1998 and everyone was very excited. And they had -- the firm had decided that it was essential to find someone who was willing to bet big, and that meant that all of the entrepreneurs who came in said I'm probably going to lose three or $4 million on this, then I'll turn it around and get it profitable. Those were sent packing right away. That was not a big idea. They wanted to hear from someone who was confident that they could lose $40 million before hopefully turning it back around. And the one thing you knew for sure about living.com, everything was chancy, but you did know that it definitely could lose $40 million on the way down. So being an embedded reporter on this, I got to watch a lot of the partners meetings where they didn't just hear from the entrepreneur, but they closed the door and said what are we going to do about this. There was a tug-of-war between the partners who were sponsoring it who felt it was their chance to have the next Bezos and the guy championing was the right guy to invest in and then the house skeptic who felt this was a ticket to Chapter 11 and it ought to be someone else's. They went back and forth and kept doing more due diligence and getting more stressed. And the takeaway point for me was sometimes you don't know. And sometimes it's very hard to pin down who is going to be successful, who isn't. And we've got a whole set of areas that we can approach very clinically and analytically. If you're applying for a mortgage, it's pretty straightforward whether you deserve a mortgage or not; we all understand the system. If you're applying to start a company, that's much more treacherous. And as I got to know other industries and other fields I felt there's a commonality here. There's an awful lot of bright people looking to find the game changing people who will change the future. And yet no one has a fully standardized set of rules, and what I'd like to do for two or three years is go travel to every place that I think is instructive and see what I can learn. So that's what led to the book. And let me take a moment to frame it a little more broadly, and then we'll start getting into specific stories. The starting point is that everyone wants Top Flight talent. In the engineering world, you talk about 10X software engineers or Mark Zuckerberg's case 100X engineers. And the war for talent is a theme you'll hear from management consultants. But are we doing any good at finding that? And the answer is it's erratic at best. There's a survey by New Talent Management Network where they asked 2,000 HR managers: Are you winning the war for talent. Only 18 percent said, yes, we are. The majority of them said we're fighting it to a draw. The war continues. And fully one in ten said, no, we're losing; we're actually doing a poorer job of finding talent than we were a while ago. I appreciate their candor. These are not easy answers to give. Everyone knows what you want to be in the green bar. You don't want to be in the yellow or red. But a lot of organizations are in the yellow or the red. What's even more striking when you ask people how are you doing on your external hires, the answer is there's only about 47, 48 percent acceptance with results. You ask them how they're doing on the internal promotions, they've gotten to know these people better. There should be a deeper sense of who you want. Scores there are even worse. So we don't know how to hire strangers, and we're stumbling around even more in how to promote the people we already know. I had enough time on this to go and read what's in the academic literature. And what struck me is, in classic economist fashion, we've gone and studied the problem that's most easy to quantify where the data is the richest and the answers are the most shallow and barren. So we know how to hire bank tellers, it's very systematized. We know how to hire low-end healthcare workers, lab technicians, the like, nurses. We know how to hire auto workers. But do we know how to hire the people and how to pick the people that are really going to drive growth in our organization? And the answer that's much less systematized. The sample sizes are smaller. The variables are much larger. There's a constant redefinition of the problem to what was a great hire in 2004, may not be the person you want in 2008 or 2011. So we've got an area here where there's much less guidance. And what I wanted to do was answer two key questions in doing the book. First is how do world-class ambitious organizations get talent right, and the second is what can the rest of us learn from them. And on a project like this, I felt lateral thinking was going to be important. We all know our own industry well. We know our own company extremely well. But there's always fields where you go I wonder what we could learn from them? The success of "Money Ball", a very popular book about how the Oakland A's pick baseball talent. That's been a bestseller on and off for eight years, very popular movie. And we go not because we care about how the Oakland A's did in 2001, but because we think somewhere there's something inside the game of baseball that could apply to our world. So I wanted to look for easily 15 different Money Ball type situations across the U.S. economy. And I got one batch from sports, performing arts, the like, where data is rich, where the definition of success is clear. I got another batch from public service professions, healthcare, medicine, law, and then I got a third batch from business. I want to start with some stories of going to see how Army Special Forces picks their soldiers. This, of course, is the elite end of the Army. These are the eight or 16-person groups that will go into valleys in Afghanistan that will stand on the border between Burma and Thailand and stop the drug trade. They're trying to do with a small number of soldiers that you can't do with a thousand or 10,000. If you look at the impact of special forces, these are the guys who got Bin Laden. And that was something that we never were able to do with a big unit, we were able to do with a very small number of Navy Seals. So the commitment to excellence to unique skills is there. And I called up all three branches and the Army said come on in. You ready to see everything we do? Sure. It's one of the questions you answer where you don't know where it's going to take you. Where it took me is the swampy pinelands of North Carolina at 2:00 a.m. in the morning. And the answer is the soldiers are there, I need to be there too. So I basically had very little sleep for two weeks, but I got to see how they do selection. Here's a place I want to start. It's a dim picture for a reason. This is shot around 4:30 in the morning. And what you've got in the center is a busted up Vietnam era trailer with one wheel missing. It weighs about half a ton. It's rusted as can be. Its mechanics have pretty much broken down. And they're going to ask small teams of soldiers to push that thing three miles through the sand and they're going to give them a handful of things to make the job easier...if they can figure out what to do with them. They'll get four long metal poles. They'll get a bunch of latchings and 100 feet of rope. And they'll have five minutes to figure out what to do with it. What they don't tell the teams of soldiers is there's no perfect solution. But if you're resourceful, you can figure out ways to use those tools to create some sort of balance, counterbalance that will make it easier for the trailer to hold up right. But you've got an engineering problem to solve in a hurry and you've got a team organization problem to solve over three hours of how do you use all the soldiers on your team to get it going forward. The key point in the field, you have to improvise. So what we've got here is a handful of soldiers trying to build an arrangement for this. They're not firing bullets. They're not shooting down the enemy. What they are doing is trying to solve an unexpected problem that may not have a great solution. And you know what, to be a good soldier, you're always doing that. That is really what the missions that define you. Now, since I assume we have an audience today, people with an engineering or technical background to some degree. You'll like this. When you've got two beams and you put them on top of each other, what's going to happen with the top beam in terms of your ability to align it to the corners? You've got some three-dimensionality there. So the guy has drawn out a sketch that assumes you can form the X and all four points will touch the base equally. Doesn't work quite that way. These are strong young men, so they completely bent the top beam on the X, so it sagged and touched the two points, but then they had a very unwieldy, rickety structure. They never figured out what to do with the rope. There is a solution for it. But some guys with uniforms are going to come after me if I reveal it. So let's just assume that the rope has a role. And they headed out for their three-mile push through the sand. And this is where you really see who is going to make it as a soldier. This is a job all about adversity and ambiguity. If you look closely, the front group of soldiers here, they pretty much know what they're doing. Everyone's pushing. Everyone's got a presence. You look at the back group there, there's one guy who has absolutely no defined role who they just couldn't fit him in. There's another guy who is falling off the contraption. And it's hard enough work. You need all eight people working. If you've only got four or five working and the others as spectators, you're going to wear down the people working and create incredible tensions between those who work and those who don't. I got to see two weeks of exercises like this. They were remarkably good at sorting out people who could work their way through difficulty and people who couldn't. If you ask what's this all about, it's a hunt for tenacity. That's the trait that these soldiers need, and that's what's going to make them effective in unexpected postings where they won't be able to be provisioned with those nice, tasty Military rations. If they are going to eat, they need to find the villager with the goat, figure out a way to buy the goat, charm the goat out of him, commandeer the goat, and still keep the loyalty of the village. The stories I'd hear of them of their deployments were one test of cleverness after another. You end in an area with the Taliban, where can you put your camp, the best place is in the cemetery because no one's going to rain down bullets on their ancestors and that way you're safe even against a hostile settlement. I came away from that going this is an interesting example, looking for intangible virtues of character and they've got a very systematic way of finding them. Let me go to a couple of other areas that I found were instructive. I got interested in How Teach for America works. Can I ask how many have either considered Teach for America or others who have done it, or siblings. So we've got some awareness, just to share with the rest of the group. This was started in Princeton in the late 1980s, meant to be a program where students graduating from top liberal arts schools could go and do two years of community service, almost a domestic Peace Corps, where you'd go and teach in some of America's most difficult schools. And in the beginning Teach for America assumed that what you wanted were charismatic, wonderful, gushy communicator's. And their showcase test question was: What is wind. And you're expected to give an answer: The wind is the fluttering of the angel's wings and wind is molecules moving through air. Something that showed that you could communicate something exciting. That's great for a dorm room. That's probably great for a senior seminar or a freshman seminar. Where are these students going? They're not going to Lakeside, they're not going to an audience of people who want to hear that high level. They've got classrooms that are struggling to keep order. They're going to go into places where there's no heat in the winter. They're going to go into places where there are 36 kids and 28 desks. And you've got to figure out what to do with the kids who don't even have somewhere to sit. And what's the trait you really need for that? You need someone with resilience, perseverance, someone who can work through difficulty. And Teach for America, to their credit, has retooled their selection system, so now what they're looking for are those students who can turn into the teachers who can thrive there. When they look at grade points. They're not looking for people who had three 8s or 9s all the way across, although there's nothing wrong with that. But what they really wanted were the people who started out perhaps from an underprivileged background themselves and had to fight to get Bs their freshman year, and then year by year took their grade point up. They've looking for people not so much who were heads of the successful organizations on campus but the ones who managed to take the smaller sports teams, less well-funded student groups and make a go of those. Their key trait: Perseverance. If you look at Teach for America's marketing and imaging now, it's: Can you get kids to read in an environment where spray painting and run-down parking lots are common. So, again, looking for an intangible trait and building up a selection system that will spot that. I watch some of their sample lessons that they were having candidates teach. And in the course of each of them they would have one of the Teach for America people start waving their hand like a kid in the classroom, and they would ask what was a totally off-track question representing what's now politely called the off-task student. When I went through school they were called troublemakers, and they were sent to the dean. But we have new vocabulary now; these are off-task students. And what a differentiator. And you could see the people who could gradually bring that kid back into the discussion, acknowledge their answer, and show them what they needed to do to get with the group, and the people that were either peremptory or rude to that kid or who were so eager to please the kid who was ultimately off on their own planet that the entire lesson ground to a halt. So they look for perseverance, they find perseverance. Let me give you one more example from far outside the world we work in, and then I'll start bringing the conversation home closer to what we do. Another area I want you to see is how do you identify a great athlete. And I figured the most interesting juncture was when high school basketball players who are competing in whatever their school is start to come into the great American sports machine, which is Division I college sports. And the good people at Nike have helped facilitate this process with a bunch of summer basketball tournaments. They're all in out-of-the-way places. I went to one in North Augusta, South Carolina, right in a gym with maybe 50 to 100 people there, and the best basketball players is a cohort I've seen. These are guys who are already, stars of Division I teams and a couple of years they'll be in the NBA, if you follow college basketball, Jared Sullinger now at Ohio State, Austin Rivers now at Duke. At this stage, they're relatively unknown high school juniors or seniors, and they're just playing for the fun of it and a chance to get notice. So who are all these people sitting on the sideline? These are the coaches of all the top Division I schools. They come here because they're going to see the best players they can. A couple of points that made a big impression to me chatting with the coaches and the professional scouts: There's 100 players playing there. All will end up in Division I. Most will end up with scholarships. But the insight shared with me, if you're looking for more than 15 players here, if you're paying attention to more than 15, you don't really understand your own program. You need to know: Are we a school that's built around tight defense, find the best defenders? Are we a school built around superb outside shooters, find the best shooters. If you're jumping from area to area, you don't know what you're looking for, you're not going to build a cohesive team. The second thing that really struck me is how much attention the scouts paid to little stuff. I sat and watched a game with one of them, and he was doing his markups. He was seeing an entirely different game to me. I was paying attention to who was scoring, who was dunking, blocking shots. He was looking at all the little stuff. Timeouts are fascinating to these scouts. Why? Because that's when you see which players run into the huddle, which ones listen to the coach, which ones give their teammates a pat on the back and which ones couldn't care less. How players handle injuries. There's one player who came in there superb physical achievements. He twisted his ankle at some point. Spent the rest of the game sitting on the floor looking away and just basically feeling sorry for himself. I'd feel bad if I twisted my ankle, too, but there was an indicator there that said, you know, this is someone that's not there for the team. This is someone that's there for themselves. And the coach said we can teach people to be better shooters, we can teach them a lot of physical skills, but we cannot change their personality. And every time -- one of the top coaches said: Every time I've taken a player who was a difficult attitude case but I was told, oh, they're just having a bad day or they're kind of quiet, I'd regret it for the next four years. So to bring it down to a nutshell, when I'm watching the 3-point shots, I'm watching something that ultimately doesn't matter that much in scouting. If I'm watching the pushing and elbowing underneath to get in position for a rebound that's where I'm seeing what does matter. So I watched all Ohio Red play a game. Their star guard scored 25 points. One of their less noticed players had five or six points and a couple of steals. And then their big guy in the middle, Jared Sullinger, had a dozen rebounds or so. And so I said, okay, what did we see? Bob Gibbons, the scout I was watching with, said Sullinger is the best player in high school these days. The outside shooter is too erratic and too selfish, he probably won't make it in Division I. And that guy you hardly noticed, he's got terrific hustle, he's going to do just fine; and son of a gun, the guy turned out to be right on all the points. He's seeing a game that I'm not seeing. Take-away point there: In sports the small stuff is huge. So diligence and good habits are the elements that lead to success. You need to have some level of physical talent. But character matters; attitude matters; dedication matters. And this is a world where, you know, the yardsticks between success and failure are so pronounced. If your team wins, you get contraction extensions; you'll be the hero of the campus. If your team loses, you're fired and they're looking for another coach. So there's a clarity to thinking about talent and performance that sometimes you don't see in a big corporate setting where it's easier to dodge your mistakes or transfer them to somebody else or shuffle accountability around. But you can't do that in sports. The take-away from there is again the importance of the hidden virtues, the small things that can speak a lot to character and importance of extended auditions where you're watching people perform over time rather than trying to learn everything in a short interview. To sum it up, the most interesting characters may have what I call jagged resumés. There's a whole section in the early part of the book that talks about the importance of evaluating people with jagged resumés. When I say that, I mean people who have got some remarkable standout skills but also some apparent flaws and knowing how to evaluate those and to move the best ones out of the maybe pile into the pile of people who are every bit as impressive as the ones that seem to have perfect resumés, is a hallmark of whether it's Goldman Sachs, Johns Hopkins Medicine, an awful lot of organizations that just pull ahead of the competition. So let me take a moment to talk a little bit about decoding the jagged resume. I should point out Microsoft's founder, Bill Gates, didn't finish Harvard. I'm going over what's familiar American lore. But it's a reminder for all the places that say we only hire college graduates. You're going to miss some of the most extraordinary people out there who didn't finish college because it wasn't challenging enough as opposed to it was too hard. So what distinguishes the best of jagged resumés? They excel on resilience, efficiency, self-reliance, desire to improve, curiosity and creativity. And I'd add management and ability to influence others without having full control. And these are five traits with a high level of abstraction. Each organization has a very high level of specificity. What will make you succeed at one place will be different than what makes you succeed at the other. But there's always one or two of those traits that surfaces as this is what's most essential. This is what we use to find our winners. What doesn't matter? Three things that I'd put on the list: Limited direct experience. A lot of theories I'm looking at are new fields that are bursting into prominence quite quickly. There isn't anyone with ten years of experience because the field didn't exist ten years ago. Or there are people moving into the field with a repetity that you need to be able to guess who is going to succeed in this new area because it just needs to be stocked with double or triple, quadruple the talent it has today. Second area, a career stumble or two along the way and we're going through an economic time that's creating jagged resumés by the millions. And when I get out and do some of the media turns on this, I get a lot of calls from people who have done fascinating things and hit a wall somewhere in 2009 or 2010. If we're looking for resumé perfection, those people are unemployable for the rest of their lives. If we're looking for people who can take their setbacks, bounce back from them and sometimes emerge as extremely motivated people, there's nothing like having stumbled once when people say, you know what, I'll never let that happen again. If you look at the life stories of just about all high-achieving entrepreneurs, they run into some walls. And that's part of what makes them so driven and so successful. And then the third area, I've chosen to word it personalities that take a few moments to appreciate. I think we like to meet polished people in interviews. We like to meet people with marvelous manners. But sometimes the most interesting candidates do not dazzle in the first five minutes. It takes a little while to realize that under that shyness or brittleness or inability to look people in the eye is someone who can accomplish a lot. And they're not being recruited particularly in technical fields; you're not looking for somebody to be head of sales. You're not looking for someone to be the TV spokesperson. You're looking for someone who can do a job really well. And I think the best interviewers have an ability to relax in all three of those directions to catch talents that stand out in other ways. So let me start to take it back more toward the world of business technology, research, innovation, and I deliberately gave you three examples from far away fields and let's now start to converge on more familiar territory. So we'll start with Andy Groves challenge, when I was getting started on this book I ended up at a breakfast where Dr. Grove was there. And as any of you know either directly or indirectly, Andy Grove is a man with many strong opinions and no hesitancy about sharing them. So I was about two sentences in to explaining this book and he said: What you need to do is go to Utah and you need to figure out how they got good at computer graphics, because we were never as good at graphics as we wanted to be. There was something there, go find what it was. The picture, by the way, is the famous Utah teapot. This dates back from the mid '70s, one of the challenges within the department was how could you do computer rendering of an image that had not just light and shadow on a curved space which gets subtle, but also has protrusions and holes and the like so as you rotate it around your view changes. And at one point the spout will disappear and come back, the handle will disappear and come back. And you know this becomes much more simple than just modeling a pyramid. So they figured it out in '73 or '74 and went on to build an enormous amount of things, far more complex than the teapot. Let me show you a couple of people that came out of Utah. Bear in mind, this was a school that had one-person computer science department in 1965. It was basically nowhere on the map relative to the MITs the Cal Techs, the Stanfords all the places the Illinois that we think of as computer science pioneers. But out of there they had Jim Clark who brought us Netscape and Silicon Graphics. They had Ed Capnell, who brought us Pixar. Allen Cay, huge impact on the Macintosh. John Wornak, founder of Adobe. There was a time in the early to mid '80s where you'd say almost anything interesting in computer graphics could be traced back to Utah. When we say traced back to Utah, we really trace it back to David Evans who is the founder and first employee of the computer science department. I spent a lot of time in Chapter 3 talking through his life story. He's one of the forgotten heros of the computer field in general, computer graphics, in particular. An army scout during World War II, and someone who literally his job was to venture around enemy lines into no man's land to see what he could learn. A pioneering designer of computers for Bendex in the late 50s, very interested in usability. Everyone else was trying to speed up computational speed. His interest was how do we make this more engaging than a Teletype terminal, how do we get something where people can actually see what they're doing. A good Mormon family, traces back to Mormon bishops and high level people. He ended up spending the first half of the '60s at Berkeley partly because it was a good school and partly because he was curious how do the hedons live, what are they all about. So he was a lifelong explorer himself. And what distinguished him, the reason that he's getting a couple of slides here is this willingness to look for people who were trying to find the frontier. And in some cases they didn't know what frontier they were looking for. And Catmill [phonetic] originally wanted to be a Disney caliber animator. He's a very good drawer, but he felt he might not be able to make it all the way to being one of Disney's top guns. He ended you wanting to be a top physicist, actually that didn't quite pan out. Ended up going to work for Boeing. They had layoffs since the Vietnam era began to wind down. So his first three careers basically didn't work out. By the time he got to Evans he was looking for career number four. But he had that hunger to get somewhere exciting and both Catmull and Clark, two very different people, said they started out in physics but it was moving to slowly. I got a sense people weren't working on big enough problems, it would take me ten years to get to the big frontier. I wanted to get there faster. And that's the kind of people that Evans pulled in. He also ran a fascinating shop. He was a kind man. Not a lot of criticism, a lot of encouragement of people. He did two things that were striking. One was to pose very simple but audacious questions to people. Basically could you do X. And X was something that was seen as impossible. And he would just leave it for them. He had ambitious enough people they would say I'm going to go out and try that. So it was a place that was constantly trying to tackle big problems. The other thing he arranged the architecture of the office so that the center of the floor where they had all the researchers, there was an open photo lab with big glass windows where everyone's latest creation was taped up. And it was sort of a wall of pride; you walked by it. If you had something interesting, everyone else could see it. There's that friendly competition, that desire to go: You know what, what Clark put up there is pretty good, but I've got something better coming. And that team pressure drove people toward excellence. It's a simple habit. It's one that I found in many great organizations, one I find every time I visit Microsoft, is the feeling of you're around great people, you're building things together. And everyone pulls their weight and a desire to kind of keep moving the level of achievement up. Evans had the tragic fate of ending up being very sick in the 1990s, not really able to help oral historians as they started coming around saying how did you do it. So we're deprived of his voice for his habits. Fortunately, his second son, Peter, had worked with him closely and had a good sense of how his dad did it. I don't put up a lot of text slides but this is one that I really did want to spend a little time on the words. This is an explanation from Peter Evans about his father and you can probably read it, but just in case anyone's in the back: My dad looked at people very differently. He hired a lot of people that happened to fail history or whatever else. Some of them you might even call scary. It didn't matter to them they weren't polished in some areas that weren't important to their job performance. What he really cared about was what they liked to do. And that is really the jagged resumé concept in four sentences. Looking for people who were passionate about what they do good at it and single-minded to the point of perhaps not being so polished in everything else. And those are the kinds of achievers he brought and achieved worldwide fame for what Utah did as a result. So where do you find the jagged resumé? This is a little statistical exercise that fascinated me. We all know that there's a lot of talent concentrated in a handful of places. If you're doing recruiting, there's a top 10 or top 20 engineering school that you'll go to where most of your good Ph.D.s or masters holders or what have you will come. It's a little hard to get comprehensive data, but there's a very nice, clean proxy and that is where the Rhodes Scholar program goes to get its people. They've been running the program since 2005. This is where Senator Bill Bradley and Bill Clinton and lots of other American achievers came in and they go spend their two years at Oxford and it becomes a launching point for what often become very prominent careers, Supreme Court justices, there's no end of people who have used the Rhodes Scholar program to go higher. And it's seen as a marker for some of America's most impressive young achievers. So you do the list, and it goes back a century. So the western schools are underrepresented here but Harvard, Yale, Princeton are at the top of the list. The military academies do well. Stanford. UW. You'll find basically what's pretty standard for the top 20, top 30 American schools, slight quirks in ranking order but it's a list that's familiar. And then you go down to all the schools that have only had one Rhodes Scholar in their history. And it's a list of schools that hardly ever register on our conscience, extraordinary places for talent, but at one point they had someone who fit that bill and that's the Messiah colleges, the Nebraska Wesleyan's, the Central Arkansas, the Sioux Falls College, and you could say those are such outliers that why bother paying any attention to them.. Here's why: If you take all those one enrollee schools and roll them up together, you've got something that ends up number six on the list and ahead of all the places that you ordinarily would go for top talent. And aggregate the long tail in any sample and you start to get something that's a pretty interesting list. You see it in business. Look at Amazon. And they sell eight million books. Books number 100,000, eight million, none of them sell that much. But it's that ability to have a list that's deeper than anything that Barnes and Noble or Borders ever had in their store. It's helped make them so successful in the book business. So there's a long tail of talent as well when you come to people. And I was chatting with one of your recruiters on earlier today and she was making a point that, yes, Microsoft will hire with great depth from the top schools but you'll also every now and then find someone from central Willamette who just happens to be unbelievably bright and may not have picked the conventional path but can contribute a lot here. I'm always impressed with organizations that don't lop off the pool of talent too early and look wider. The question, of course, is if I'm telling you, you know, it helps to look even wider, how do you deal with that in a world where anyone who does recruiting or for that matter anyone who has brought in as a technical interviewer feels we're seeing too many candidates as is. The field's cluttered. The metaphor here my desk is already stacked with piles and piles of resumés, I'm looking for one person, how much needle in a haystack can I possibly put up with. So in the book, in chapter 6, I tell the story of something Facebook did. It's probably something that any tech company does and I just had the good fortune to find people who were willing to pull back the curtain a little more on the process. And that is to -- I'll open up a puzzle program where you're looking particularly for coders and to give them challenging, gnarly, long problems that can take three hours, six hours, 40 hours to solve. There's no pay. There is an e-mail address at the end that says send in your solution. When you do that, it's got two or three wonderful things going for it. The first is you're finding out who really wants to write code as opposed to who just wants to have a well-paying job at a tech company with free sodas. And they get 70,000 solutions a year. Second good thing is you can score them all automatically. You run them through and either the program works or it doesn't. The ones that don't work you slough them off of the system without burning up recruiter time or interviewer time. Your cost per candidate is probably a cost of a fraction of a penny. Then you identify the ones most interesting. Bring them in for interviews. And pursue more deeply with the most interesting pool of that. So out of Facebook 70,000 that have solved their puzzles, 118 have gotten jobs. In some programs that would be a miserably low yield. There's no way you could sustain it. The more done automatically. We're moving into an age where resumés are being searched for keywords where people's Twitter streams are being paired with their LinkedIn profiles to get a sense of not just what they've said they've done but running commentary on what they've provided on their actual work. You can look at what people contribute to chat boards and get a sense of who is a thought leader and who is a sponge and who is a parasite. And we've gotten ability now to handle those big stacks of resumés more effectively than we did before. And to start to find interesting candidates without burning up nearly the resources previously. So there's a middle section of the book that talks about talent that whispers that looks at ways that you can look at the long tail of talent without burning up resources or energy or optimism. And I would expect the hiring market gets to be more and more widely posted, more digital. I mean I was hearing stories today if you've got 80 to 90 applicants per opening and that's in areas where you don't even aggressively post. If you aggressively posted you could get 500 or a thousand per position. We're at a stage how can I sort through that many. The talent whispers through the book talks about how to do that. Big lessons looking for hidden virtues, and I think in many organizations the interview process is broken. It's more an affirmation of what people have on their resumé and a search for superficial affability, do I like this person, do I want to go out for a beer with them. Some of the best people in an organization are not necessarily your drinking buddies. They just happen to contribute a lot to what's done. And I have my checklist, but I think the first step in any organization is to figure out what do we really want, what defines us? What's the traits we need, sometimes it can be very distinctive. Linear technology relatively small chip company but incredibly prove profitable. All they do is the analog, they do the little circuits. But they make chips for three cents, eight cents and they sell them for 50 cents. It's good business. But they need designers who are willing to fiddle and tinker with the circuitry that helps a hybrid car battery run well, that helps the flash and the cell phone flash. And they need people who are basically willing to make 40 to 50 attempts at a circuit and keep coming back and redrawing it and redesigning it every week until they've got it just right and what they want is people who have been tinkering with electronics their whole lives. When I talked to engineers, they're all the people that electrified who bothered the neighborhood cat or made buzzers that would torment their sisters at age 12. It's a way of life of the those are the kinds of people who will stay and build their circuits. They probably wouldn't be good Intel engineers. They might not be the right sort for Nvidia, but they're the right sort for linear, the ability to say these are our people, these are our tribe, it's crucial. Next area, this is one that comes from Todd Carlyle at Google, staffing director. Google I often think of as one of the most centric organizations they finally stopped asking for SATs which I always thought was really strange. A lot of stuff has gone on in life beyond taking the SATs. But anyway they still look for top grades, top scores. But Todd's point is read the resumé upside down. Often the things at the end, the oh, by the way, I'm a life master bridge player at age 21. You go, wow, that's a lot of hard work to get there. You're clearly driven to be successful and focused in achieving in something. If we can bring you around to what we actually do, you might be a good hire. Community service and some other types of jobs. But that ability to go all the way down to the end of the resumé and say who are you, what are your passions, what are your energy, how pumped up can you get for something? That starts to surface a whole interesting set of candidates that otherwise we're trying to make fine-grained distinctions of is a 38 from the U a better than a 39 from Gonzaga. We're all bright people. And the differentiator is going to have much more to do with behavior motivation than it is with fine distinctions grade points. Last area, and this is one that I've been reflecting on for a long time. A lot of our culture orients around asking what can go wrong. We do stress tests. We do safety analysis. We do what if analysis. We spend the final stages of interviewing job candidates looking at all the reasons to disqualify them, their credit scores, their driving records. We run criminal histories. We run drug tests on and on. There's validity to all of that. You don't want to hire people who have got some of those problems. But we've tended to try and select out with such intensity that we've lost the ability to select in and jagged resumé candidates, these -- the way to find them is to ask what can go right. What's the best thing this person presents. There's always time later down the road to look for reasons to disqualify. And the ability to take small chances on people, internship programs are spectacular for this. People come in for three months or extended internships for a year. There's no guarantee to keep them any longer. It's a great way to try people where you're not sure if they're going to get it or not. But there's something in their application in their potential that says this could be a scholar for us. I've worked in organizations with strong internship programs and it's surprising how many of the people who get five, six, seven promotions came through the internship program. The people that you hire fully made get one or two promotions and that's kind of where they lock in. Awful lot of the interns flush out, too. But the best ones end up more than justifying the time on the others. And the final point, if you believe in someone who knows that they're a jagged resume who knows they're a little bit of a chance that's someone that's going to respond with remarkable loyalty and drive and I think some of the A team hiring practices of find me all the A players end up getting people who, yes, they've got great skills but if they don't buy into the organization, they're not going to be there long and they're not going to be effective contributors. So that ability to make the most of motivation and people's desire to succeed, something that sometimes gets lost. So let me close with a little bit of humility. I could have shown this slide plenty earlier and perhaps I should have but I do want to make sure I make these points. This book is a conversation starter. It's not meant to be the definitive answer. I've done a fair amount of hiring in my life but there are people in this room who have done vastly more than I have. I interview for a living but I interview primarily to gather information, not to form yes and no judgments on people. I've done some of both. But I have a great deal of respect for people who live in this world and I don't want to suggest that I have answers you've never heard before. What I do bring are stories from worlds that you might not be visiting, and I think judging talent is an area where the wider we look the more we see. One of the book reviewers referred to this as the money ball of HR which was a very nice thing to hear. And I hope some of the stories that you've heard have not just been entertaining for a moment but are ones that have made you think about you know what they've got an idea I actually want to chew on for a little bit. And so the other point is this is a long process. And we've moved from a world where competency-based hiring was enough to fill most of the jobs to a world where jobs keep changing. They're subtler. The requirements are different. The human-to-human interactions become much more complex and more defining. I was just chatting over lunch with how you develop ideas that go back and forth between the research lab and the product teams. And you'd think that's a technical technology transfer area to some extent it is. But much more than that. I'm told it's an issue of people and it's an issue of trust. And the people are going to be most effective at that are the ones who do have those kinds of intangible skills that I was running through on that list, that ability to connect with people. So we've got a lot of work to go to figure out how we redefine our evaluation metrics, our talent metrics, the way we search, the interview questions we ask or don't ask, the settings we want to see people in. We may find we learn a lot more about people outside the conference room and the interview chamber and going for walks, going for meals with them than we do just kind of sticking in this very artificial formal process. But I'd like to think this is a book that can help us get unstuck. If our feet have been pointing in the wrong direction at least this is a book with some ideas and suggestions of how to get to a better place. Parting thought. If you take away only one idea, make it what are the jagged resumés in my world and do I know how to spot the best ones. And what I've discovered, of course, is a lot of times my audience is the jagged resumés. And we've all had our ups and downs and sometimes it's the downs that have given us the strength to go on and do new things. So that's what I wanted to share with you today. I'd be happy to take questions on anything that relates either to Microsoft world or to anything else in the talk, and if there's just some observations you want to share, that would be great, too. Thanks. >>: What about persons who are in, say -- actors, I know they come in for a reading, one opportunity. Of course they have resumés that may show where they went to school and other things they tried out for. How do you identify someone who has star quality and maybe longevity vis-a-vis the Broadway or what would be attractive to directors over the long -- that type of thing. >> George Anders: There's an interesting transition that's happened here. I would say 40 or 50 years ago people were trying to make that once-in-a-career bet that you would sign up Rita hey worth at age 17 and you're going to be a star and we'll put you in a bunch of movies for the next ten years. Now it's much more of a project-by-project basis you get people for that one particular role. There's no end of people that claim that they discovered Tom Hanks. And discovering Tom Hanks existed of having him carry some sets at a theater for a bit and one tiny bit part and Tom Hanks moved on. In a way because it's such a chancy and iffy process, by and large we've let each person cast the right person at that moment and see how they progress upward. But every now and then there are latter defining moments. There's a great story about Julia Roberts. I'll try and tell it quickly. But she was a small fringe actress for a time and Mystic Pizza ended up being her breakout role. She was the girl engaged and was going to get married and it all fell apart and eventually she sorted out her life. But it was the classic sort of aspiration and achievement and confusion and tears and smiles and it's a perfect Julia Roberts role. So she shows up for the audition and it's rainy and she's lost the script and she's not prepared. You could be strict and you could say you've got to bring the script, you've got to be prepared, that's an instant flunk out. But the casting agent who was evaluating her, there was a little bit of her who said the role she's being cast for is the kind of girl who would forget to bring the script. She looks right. She's engaging. She's done well in her other things, and they said come back tomorrow. Here's another copy of the script. You do need to bring it the next time. We can't make a habit of this. But I'm going to give you a second chance. And the second time she did a knock 'em dead reading and got that. So I think there's that -- to sum up, and sometimes there's no one Eureka moment. People just gradually move up. But where there is, I think it requires an ability to stretch beyond the definition of the role and to see what else people can become. And I spent a bunch of time with casting directors, and they're very much in the world of potential and positives, and then they rein themselves back in but there's that early moment where you go: What can go right? And see what that best actress or actor can be and time to criticize afterwards but open the horizons first. Yes? >>: I actually have two unrelated questions. >> George Anders: Sure. >>: So the first question is how do you feel about this finding talent versus creating talent, as in the stuff that [inaudible] talks about his book Outliers. In other words, the effects? >> George Anders: So I'm going to condense down the Gladwell thesis but there's a great deal of what he says you do your 10,000 hours of practice. Do your concentrated work that stretches you. And that is a hallmark to success. And I think we've got a causation correlation problem there. It's wonderful that the Beatles played several days in Hamburg all hours of the night. Figure ought how to do nine hours of music, keep finding new songs. But you know what, there are a lot of people who played long hours in dinky bars and they never sold. Yes, hard work will make anyone better. But I also think people's capacity for hard work is something that is not instantly transferrable. And I'm sure you've seen it in your area. There's some people who can still be doing good work at seven and eight in the evening and can do it pretty much six, seven days a week. And there are other people that may still physically be in the office Friday afternoon, but they've checked out. And I think that's a differentiator that just about every field I talk to that ability to gauge dedication, motivation. You can't remake people's personalities. So I think there's a lot of good stories and good insights in Gladwell's work, but I would still contend the spotting role is crucial, that it's not just a matter of we can all build ourselves into whatever we want. Question two. >>: Second question is actually more personal question. Like how did you come into this field? Like where were you coming in from? I know it's been a long time, you've been in this field for a long time, I guess. But ->> George Anders: Sure, whenever you ask almost any writer or journalist we have fairly incoherent career paths. This is one of the few socially acceptable ways is you can have ADHD your whole life and still be paid for it and even rewarded for jumping around. So I did an undergraduate degree in economics at Stanford. I loved writing. I was probably more involved in the college paper than anywhere else. I saw writing about business as a way of fusing the two great strands of what I was doing. Then at the Wall Street Journal I moved from subject to subject. Get knowledgeable at finance, did a book on that. Graduated or transferred myself on to healthcare. Did a book on that. I completed that. It was time to enroll in another program, it was learning about high tech. And as I moved from area to area, I was going it would be nice if there were some commonalities here. I'm enjoying the sense of constant discovery, but is there anything that links them. And of course what links them is people. They're all high-achieving, ambitious sometimes perilous fields. There's no guaranteed path to success. And that's what drew me into this book. So I try and be open minded. Reasonably bright. But the one thing I'll test off the charts on is curiosity. So I figured bring enough curiosity to the subject and we'll get somewhere good. >>: Thank you. >> George Anders: Yes? >>: Your first anecdote, it's interesting Daniel Cameron was here about a month ago. He wrote an article in the New York Times about similar testing of the Israeli military where he and his colleague conducted some research. And they looked at the correlation between success in that test and actually future success of the people and he found no correlation whatsoever. So my question is whether in the overall research, apart from being wowed by some of the anecdotes of -- the things that you saw that are really proven to be effective in some scientific way ->> George Anders: I want to draw a distinction because the comment anecdote is wonderful. He's got an Israeli military example where they're trying to move a log over a wall and they're trying to infer all sorts of things about leadership style, about how you move the log. And the big message I'd share it's possible to do an awful lot of cheesy simulations. And in fact the simulation field has been troubled by things that are artificial, brief contrived and in the end you try and extrapolate results that aren't there. What I liked about the example I showed it's much more sustained, and this is not an effort to put people through an ardeous 15 minute march and see what they do. This is an effort over the course of two weeks to run people through something pretty similar to the stress of being in a military engagement and having to form either retreats or attacks or what have you, day after day, after day. And they're really only looking for one thing, which is how well do you hold up on tenacity. They're not looking for deep insights into who the leaders are, which is a much more subtle area. So I think the U.S. Army 2009 is using a test that's both better built out and much less ambitious than the Israeli Army which was trying to, in the 1960s, come up with a one-hour test that would tell you everything about people. To answer your question about data, yes, the U.S. Army sits down and goes, okay, who did we take in, what did they look like at the time of review who are successful soldiers. And turning the clock backward, you can go the people we thought were good are good, or the exact situation he pointed out were picking the wrong people. And in fact the U.S. Army did a lot of retooling because there was a time they were subjecting their soldiers to a great deal of screaming stress and they could flunk people out that way pretty quickly. But they realized you know what that actually doesn't happen in a battle. What's much more common is loneliness and isolation. So they got rid of a marker that wasn't helping them find good soldiers and moved to one that would. So I like the underlying drive of your question, which is validate whatever you think you're knowing by multiple years of looking at the people you choose. And the answer is in this case they did. But [inaudible] stories perfectly valid and it's a sign of how we've moved forward from overly simple cheesy tests in the 1960s. >>: With the jagged resumé thing, what is the trade-off between that jaggedness and that core skills? If you go back to the Green Beret example you talk about how they're not having them shoot as part of these exercises. Presumably you want them all to be able to shoot. Be comfortable, be comfortable carrying the weight of their equipment, things like that. Those are all basic qualifications for that job, that those candidates have already shown they can do before they get to that stage. So what is that trade-off between that jaggedness and looking for the interesting pieces of the resumé against that core skill set those things or is the suggestion on the jagged resumé thing to not pay as much attention to those kind of that baseline. >>: I'm glad you brought the attention back to that to answer first literally for the special forces and then by extension everyone else, in this case all of their candidates have served in the U.S. Army for at least a year or two and most of them for five or six. So they've got some level of basic sole searching. They've taken some sort of rudimentary IQ test to make sure that they are not genuinely dumb. You can't unteach dumb. And they've passed a physical review that's been dialed down a little bit. There's a time where they were looking for sort of pushup champions. You don't need that, you need to be strong enough, but that's why the internal combustion engine was invented. We don't have to do everything with brute force. So, yes, you need some sort of gating to make sure that you're dealing with people who are at a basic level of competence. But once you get to 50th percentile, 90th percentile, whatever the cutoff, where buying more a little more on the sheer credentials and proven, historical competence isn't buying you as much as looking for the motivational tools. Yes? >>: Observation and a question. The observation is I read somewhere [inaudible] survivors of the holocaust, concentration camps. And what is the attribute that actually helped them survive six years of being in a concentration camp. The answer was resiliency was the point. Because he said the people who give up are the people who [inaudible] the optimist said this Christmas I'm going to be back home. This Easter I'm going to be back home. When it was not happening, they just, most of them just gave up because their heart gave up. The resilient ones are the pessimist saying I will survive this and get out and [inaudible] I think it's a good thing. The question I had for you was around the global nature of this. The attributes you talked about, the global talent search, company like Microsoft, looking in multiple countries, all over. Do these attributes apply as such? Is there a variance of this that you see when you look at global talent? >> George Anders: So each country is its own story. I was in UK and Ireland talking about the book a month or so ago. It connected very strongly with the UK audience, particularly recruiters who felt that they were victims of a system that was way too credentials focused and that there were a lot of very capable people who were not getting through the pipeline who should. I'm not sure it connected as much in Ireland. And I'm going to get myself in trouble if I try and explain Irish social strata, but we found marketing book there's interest in Brazil and there's going to be a Brazilian edition coming out. There's some interest in China but threes also reminders of Chinese talent evaluation systems are very different than what you do in the west. And I think building up of national champion universities is early enough in the stage that at this stage you want to be proud and confident of the people who are coming out of universities who are doing things that just weren't there ten or 20 years ago. So I'd be hesitant to generalize about the whole world. I think there are other countries where this approach makes sense and there are probably others where just talent pathways flow differently. So -- yes? >>: A lot of what you were talking about that made me think a different recent college graduate, one of the most -- what hit close to home for me were all the times that I spent studying something that I completely found irrelevant to what I actually wanted to end up doing, simply because I wanted to make sure that I was going to have that upper echelon resumé and I don't than if there's something that can be done systematically throughout educational institutions that allows people to specialize and become more focused earlier point in their careers as opposed to needing to think about such a broad aspect of different skills simply out of worry that they're going to be restricted in terms of their opportunities if they don't divert their progress. >>: I really like the question because I think you touch on two crucial public policy issues going forward. I mean, we're still living with an early 20th century model which says you go and get four years of college and then however many years of masters in Ph.D. and at that stage you are a fully educated person, and my goodness we live in a world now where the areas you need to know about are constantly changing. Schools cannot anticipate them all. And would we serve ourselves better by having shorter stays in university at the early stages of our careers and return refresh mid-year education. The other thing is the original college mission was to make you a well rounded person and they were very explicit western civilization things and great works of literature to read and that was part of seen as being a cultured person and I always felt as an used graduate I could read books on my own time and to go and spend a year out of the workforce essentially working through someone else's reading list, there's always time in the summer to do that. And so you don't want people who are so tightly trained in one field that they have no sense of being a citizen of the world, whether it comes to something as simple as voting intelligently or having a feel for your dynamics of your business partners and other cultures. But I like the direction you're headed which is maybe we can condense the amount of time and let people pick up the skills they need to get started and then come back into the education system, either for brief sabbaticals or mid career retraining, and can I ask which school you went to? >>: Actually went to a technical skill went to Rochester Institute of Technology. >> George Anders: Okay. >>: And my main concern is probably not the same as someone who went to a liberal arts school. But it was more on the ability to start research early on and to perhaps have more time even in undergraduate devoted towards doing research and getting established in that aspect of your career as opposed to necessarily spending time like say, for example, in a statistics class, I could be spending that time a separate aspect of mathematics. I don't have a very well formed thought. It's more there are certain areas that they want you to develop maybe mathematics or your ability to do about a systems engineer or whatever they want you to do. They already have a defined curriculum that perhaps could be more malleable to the actual interests that you have towards the research goals that you want to pursue. >>: I always like the people who figured out how to wiggle their way into the Dean's office and say I want to design my own major and it takes a fair amount of nerve to tell him that at 19 or 20 you know more about what's a relevant education than they do. The answer is you may actually know that. You may have a better sense. So ideally schools will let people write their own ticket to a greater degree. >>: Listening to what you're saying from a recruiting perspective, a lot of very individual things you could do, look at the jagged resumé and think outside the box and influence groups to assess talent slightly differently. Do you have any opinions on what can be kind of done more on a corporate level, to influence that culture or open the gates to jagged resumés a little more [inaudible]. >> George Anders: So I did a talk for small company CEOs and the stress points that came back from them were I'm ready to take chances on interesting people. But my board wants me to do pure competence-based hiring and find people who have done the same basic job for ten years even if they're burnt out and aren't going to give me a lot because they look safe. Or even worse my junior managers aren't ready to get someone who ventures in a different area than I do. And at Microsoft you don't have the situation of the board second-guessing the CEO because of the classic venture tensions. >>: Compliance and things like that that say they have to have these basic qualifications, things like that? >> George Anders: Yeah, and you usually need individual champions to change culture like that. And I think the stories I've been hearing are the individual team leaders, project directors, the like who are willing to say you know what, let's try something different. But it is pushing against the barrier. So I think it's one of the ways the big companies can kind of ossify their culture is they become much more concerned about hiring someone who is safe and fits all the checklists and if you look at why some of the largest companies have just slowed down as innovators that can be a big part of it. But I think it's just kind of one individual rebel after another looking for the best thing can do within the system. I wish I had some sort of automatic fix, but I think it's more kind of case-by-case. >>: What companies space have you seen -- look at the jagged resumé, take up risks. >> George Anders: Mozilla will do that sometimes. Facebook is schizoid, there's some examples that they do really well and there's some other times where they're eager to keep getting people from the same schools with the same background. I think they are a bit more flexible on educational achievement just because so many of them, the early generation kind of baled on whatever they were doing in school so that sense if you can write code, that's as good as having stayed in school for the very last program you could have had. HP globally is doing interesting things. And I think probably in a way the farther away you are from Palo Alto the more interesting things you can try. And it's an interesting tension of just being close to headquarters help you innovate or does it tug you toward conformity, it varies a lot company by company. But I think the one great thing about high tech industries at least people are asking that question. In a way one of the things I wanted to do with jagged resumés is give people a term that would let them say what I'm trying to do here is under a framework that can sometimes work spectacularly and you still need to fight all the battles of are we going to do it this particular time with this particular person. But I came into it and felt there wasn't even language to talk about that that it was all so hopefully I've contributed something that at least makes it easier to have that conversation. >>: I think that will be the last question because I snuck it in there. >> George Anders: Well done. >>: Everyone is interested in getting your book signed. Thanks for coming. [applause]