Document 17879184

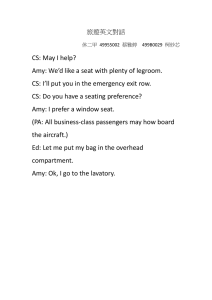

advertisement

>> Amy Draves: Thank you so much for coming. My name is Amy Draves and I’m pleased to welcome Amy Wilkinson to the Microsoft Research Visiting Speaker Series. Amy will be discussing her book the Creator’s Code in which she reveals six fundamental skills that highly successful entrepreneurs use and we all can learn. These can be used for both launching new companies and for launching successful initiatives in your current role. Amy is a strategic advisor and lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Business. Her career has included leadership roles at McKinsey, JP Morgan, and her own startup. She has served as a White House Fellow in the office the US Trade Representative and a Senior Fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School. Please join me in giving her a very warm welcome. [applause] >> Amy Wilkinson: Thank you, thank you. Thank you for the introduction. I’m absolutely thrilled to be at Microsoft. It feels a little bit like a homecoming to me because I grew up in Tacoma Washington. I just flew in this morning from New York. I was just so excited to actually see the mountain range and to come into the city. I grew up here when it felt like Microsoft was growing up. Now it’s just exciting to be back here because it’s such a big and interesting, and world changing place where you guys work. I’m truly, truly thrilled to be here. I will start with a tiny; it’s a one and half minute video clip. I’ve done five years of research most recently at Harvard and interviewed two hundred of the top entrepreneurs in the United States. For a book that came out last week. It’s exactly one week into the market called The Creators Code. That’s what we’ll talk about. I’m also, first time writer, and very, very excited because it’s the number one on Amazon in the Business category right now. As I came into Seattle it was like hurray Amazon and Microsoft. [applause] I’m like it’s an exciting place up here. I’ll give you guys a minute and a half clip. Then I’ll tell you the six skills. But this will hopefully be interesting because it shows some of the people in the book. [video] >>: You feel you’re changing people’s lives. You’re saving people’s lives. I think that’s just incredibly highly motivating. >>: I made the same shirt for five years. >>: Right. >>: Over and over, and over again making it right. >>: Entrepreneurs are an interesting beast. >>: You’ve got to get use to this idea that people are going to say no to you. But you’re going to do something that, it might not work. >>: You don’t worry about failure? >>: I worry a lot about failure. >>: Oh, you do? >>: Yeah, absolutely. I feel fear quite strongly. >>: It’s not about the money. It’s really about creating something special and to getting people excited in making a difference. >>: I remember with the lights going on thinking wow this is what I should be doing. >>: There was something, something that lived inside of us. There was a spirit that we couldn’t shake. Right, there was all this logic that was around us telling us to stop. But there was something inside of us that we couldn’t ignore. >>: He gave me this great piece of advice because I had spent so many hours fiddling with this. He said Robin, start and then once you start is that you can change it. We stated. >>: That is the number one message that I want people when they see or hear the Under Armour story. I want them to look at it and go you mean that that football player from Maryland could do this. Oh, geez, I mean I must be able to do this too. Like good then go do it. [video ended] >> Amy Wilkinson: That’s the research that some of those founders will talk about. I’m not exactly sure what this is, okay good. Its five years of research, two hundred interviews. The criteria set for figuring out who some of the leading entrepreneurs were in the United States, right now. Is you had to have found a company and scaled it over a hundred million in revenue with five years of history, and not more than ten years of a ramp. These are younger entrepreneurs than the Microsoft’s story. They are currently, a number of them leading in their industries. It’s also across industries. The Jet Blue founder was here, the Airbnb founder, Under Armour, a lot of the Silicon Valley Tech companies. But I was very specific to look across and then identify what came back as six skills that anyone can use. The other big part about this as we go through it is the Creator’s Code, the word Creator is very intentionally used. You don’t have to be an entrepreneur. You don’t have to be a founder of a company. You can create an idea here inside of a very, very large company like. The idea is the six skills very much so apply inside of a place like Microsoft. Or it’s also in the non-profit world. We can take these ideas and create, and scale concepts not just by being the founder of a business over a hundred million in revenue. But that’s the dataset for trying to figure out who we would like to emulate and who has actually figured this out in the last ten years, five to ten years, in a pretty substantial way. I’ll say a little bit about how I got into doing this. I had the great privilege of working in the White House. I was a White House Fellow. I did four years of International Trade and Economics. While I was doing that at one point I was invited to a birthday party in fact in New York City. I went in to New York and it was in this sort of dark basement place, kind of strange birthday party. I looked around and the founders of Google were there, and eBay, and Gilt Groupe, and a number of startups that were so fascinating. They were changing the world like in lightening speed. I was in the White House. These people were just doing things. No red tape, no big bureaucracy. They were truly standing up concepts that were changing the way that we were living. I’m trained as a sociologist. I have a Master’s is Sociology. I’m also trained as an MBA so I’m fascinated by people and especially the people behind business. I thought to myself if I could just study what these really fabulous entrepreneurial creators were doing. Then distill it that other people would also be able to go and do that too. That was the genesis of the project. I thought it would be a quick sabbatical. I came out of the White House and I thought I would do that you know really in about twelve to eighteen months. It’s taken five years and a huge amount of research not only in the market place as first interviews but also I’ve looked across academic disciplines. Cognitive Psychology or Behavioral Economics, or Creativity Research as a field of the entrepreneurial research is a pretty young field. That’s the basis behind what is now the Creator’s Code. This is the story and you saw, this is the story of Kevin Plank. You saw him in that short clip. But he is the football player right here. He’s a walk on to the University of Maryland. He’s five ten when he walks on and two hundred and sixty pounds. He’s not a great athlete. He’s not a great football player. He’s in Division one. He basically was the slowest player. He’s known as Maryland’s sweatiest player. [laughter] He at one point in time weighed his cotton t-shirt that was under his uniform and it weighed three pounds. He basically said I can’t afford three extra pounds because you know I’m not all that great to begin with. He went to a local fabric store in College Park Maryland and found out that synthetic fabrics would wick away moisture. Then he took this stretchy bolt of material and he took it to a tailor. Four hundred and fifty dollars and seven prototypes later he basically came up with what is Under Armour. It’s a two billion dollar global brand now. He outfits big football players like this and across multiple sports. But the little known secret about Under Armour is that big tough football players like the same fabric as is found here. Under Armour is using the same fabric as Victoria’s Secret. That’s what Kevin didn’t tell all these football players when he first started. Was that he had figured out the fabric and he’d gone to the tailors. He was in the Garment District in New York. He found a mill in Ohio. I mean he was just driving this old Jeep Grand Cherokee everywhere trying to figure out how he would solve his sweaty problem. It’s an unusual solution. But it’s one of the things that I found over and over in my research is people would look in places that other people wouldn’t look. That they would basically take solutions that other people might not have thought of. The power of six, this out of all of the research basically is a grounded theory method. It’s a very nerdy sociology methodology. But what it comes up with is six essential skills. They work in concert. We’ll talk about each one of them. But the kind of big take away here is that we might naturally be really good at two or three of these skills. But people who are creating and scaling ideas they’re really doing all six. Its when these are combined that the magic happens is when we learn and practice, and hone all of them that we can really scale our ideas. The first is what I’m calling Find the Gap. It is very much being a detective. It’s how do you see a gap or how do you spot something that other people don’t see? The research informs three ways that these creators are doing that. One is as Howard Schultz, so there’s another great Starbucks Company. Hooray for Seattle, I’m just, so amazing. He didn’t actually invent the coffee concept, right. He saw it in Italy, so he and he brought it home. That is what I’m calling a Sunbird way of Discovery. There’s quite a lot of research around reasoning by analogy. Can you see something in one place and then can you pick it up and fly it over, and apply it in another place? The Sunbird is actually the Australian word for hummingbird. If you think of like being a hummingbird what Schultz did was he saw a coffee culture in Italy. Then at the time here in Seattle I mean people were having coffee maybe at home or in diners. But there weren’t really coffee houses that people were going to. He brought it back. But first it didn’t work as well as it does today. He had bowtie clad waiters. He was having opera music in the background. It was a standup bar. It looked very Italian like he had actually seen and loved. One of these concepts is that you see something but you transport it with a twist. You apply it in a place with some kind of a little modification to it. Starbucks obviously has done very, very well. Another way of seeing is what I’m calling an Architect. This is Elon Musk. He’s extraordinary. He’s trained as a Physicist. I think he’s very much Albert Einstein as a Physicist meets Steve Jobs. He loves design. He’s the co-founder; he’s the founder of SpaceX, co-founder of Tesla Motors. He’s the co-CEO of both companies right now at this time. SpaceX as an architect, what architects do is look for just as an architect would an open space, right, a green field. Then they build concepts from the ground up. Trained as a Physicist, Elon is a great example of reasoning by first principles. He’ll talk about going right back to the very fundamental ideas and then building them a completely different way. The SpaceX Company is now resupplying the International Space Station at one tenth the price that NASA did. He’s building a reusable rocket. I don’t know if you’ve all seen in the headlines the last couple weeks. But it’s an extraordinary way of reasoning that we weren’t doing before. I mean no government was thinking that we would build a reusable rocket. We would you know have it launch and then have it land on a sheet of flame or in the ocean. Now they’re building platforms right to try to have these things land. But Elon thinks about it and he basically says no we’ll just, that’s how rockets should work. I mean I have him on transcript saying that’s how it should work. Nobody has just thought about it working like that, yet. If you think that every time we would fly between Seattle and London, or New York we would throw away the jet. It would be pretty expensive to be flying around. That’s basically what we do with space travel. You know we are throwing away rockets. We’re not recycling or reusing them. It’s a way of seeing the world. To think that you have to build a rocket, it’s not right. The Spanx founder is also an Architect. This is a very every day problem that she sees. She cuts the feet out of her nylons and she’s the youngest self-made female billionaire in two thousand twelve. Who here knows what Spanx is? Okay, so we have a few men. What men in the room need to know is that Manx is coming. [laughter] Do you guys know what Manx is? It’s like the compression shirt for the stomach. Basically Sara Blakely is also what I’m considering to be an Architect because she sees an unaddressed need, which her story is extraordinary. She was in Atlanta. She was a door to door fax machine saleswoman for seven years. She was trying to wear nylons under here white pants to look more professional as she was going door to door to sell these fax machines. Then when she cut the feet out of them because she wanted to wear open toed shoes, she went to a local retailer and said you know is there some kind of undergarment that I can wear that will make my white pants look better? She kept getting no, no this doesn’t seem to exist. She went and built it and because she was a door to door sales lady she also went door to door at all the manufacturing mills in the southeast until she finally got someone to make a prototype for this product. That’s another way to think about being an Architect. Then the third way of seeing is as an Integrator. This is Steve Ells at Chipotle. He’s a classically trained Chef at the New York Culinary Academy. But he was working in San Francisco at Stars Restaurant and loving burritos. He just loves burritos, hanging out in the Mission District, and starting to think about ways that you could make fast food. Not just hamburgers that would be frozen and reheated. But they could actually be something that you would cook in front of you. This became cooking for the line is what Chipotle’s model is. You actually see people cooking ingredients. Its fresher ingredients but he comes up with fast casual. It’s an integration of two different concepts. If you think about it like you know the luxury SUV. That we use to have luxury vehicles or alterainne vehicles. You put that together you have a whole new category. Or shabby chic in the design world, you know you have something that looks informal but it’s a nice design. It’s another way of trying to see things by looking at what you could put together, how you would go to an intersection of ideas and create something new. Skill two is what I’m calling Drive for Daylight. I actually enrolled in NASCAR Driving School for two weeks. The analogy is that race car drivers that are managing speed always look for the light on the horizon. They’re not looking at the lines on the payment. They’re not looking at the competitors’ right next to them because they’re moving too fast. This is what entrepreneurial creators are also doing. This is Elizabeth Holmes. Has anyone heard of Theranos and Elizabeth Holmes? Okay, good a few hands. I truly think that she is the next Steve Jobs. She wears a black turtleneck every day. [laughter] I think she’s also trying to portray this image in that she’s going to revolutionize the healthcare industry. She has spent ten years driving for daylight or looking to go thinking. I mean look only ahead. She dropped out of Stanford University as an undergraduate at age nineteen. She’s just turned thirty. She’s been in stealth mode in Palo Alto for ten years. What she’s doing here is holding a little tiny nanotainer. It’s got a couple drops of blood in it. With two or three drops of blood she can turn around two or three hundred tests in a couple hours and wirelessly deliver results. She’s just now signed a very large contract with Walgreen’s. This will roll across our Walgreen’s Pharmaceutical outlets to being really a very wide spread technology. Her idea is if you have a few pin pricks of blood and you look at data analytics from your blood stream that you could detect disease. We would detect and eventually prevent disease instead of waiting to see that we have a tumor and knowing we have cancer. We might be able to see through smaller tests done more frequently that we would be; on that progression we could stop it. Or instead of knowing that we might have heart disease by the time we have a heart attack. We would also be able to prevent that if we had these little pin pricks of blood taken very easily and locally. But in order to build this she’s been thinking about it and working and building a team for ten years. She operates from the former Facebook headquarters in Palo Alto. It should be coming on the screen I think pretty quickly here. She was the cover of Fortune Magazine about a month ago. The To-Go Thinking point is one that I find really interesting. There’s research out of the University of Chicago that show that when you’re committed to a goal of any kind. That if you think about what’s left to go that you are a lot more likely to achieve it. You throw energy, focus your brain, the cognitive capability is actually focused on getting that done. The research has shown if you’re running a marathon and your, you know twenty miles in. You just think to yourself my feet hurt, my legs hurt. That’s you know thinking about what’s not left to go. If you actually just think of the miles left to go you’re a lot more likely to complete. Same thing with students as they get through an academic quarter or semester, if you think oh I’ve only completed forty percent and I have sixty percent to go. You’re less likely to complete that course. There’s a lot of research that shows that focusing on what’s left will actually help you accomplish it. Another thing with Driving for Daylight is Scanning the Edges. This is the Airbnb concept. Have people here used Airbnb? Okay, a few, not that many, wow, I’m sort of surprised. This is very much an idea that came from the fringe into the mainstream. The story is of Joe Gebbia, he was in the short clip, and Brian Chesky. They were designers, Rhode Island School of Design, designers living in San Francisco. Their rent went up twenty-five percent and they couldn’t pay their rent. They didn’t really know what they were going to do. But there was a big design conference at that time in San Francisco coming in that week. They noticed that the hotels were sold out. They put up a little notice online that said hey we have some air mattresses and if designers want to come and stay on our air mattresses we’ll charge you a little something. But we have space. That was the genesis of Airbnb. Absolutely no venture capitalist wanted to fund this. It was not an idea that made any sense like renting out your couch or your mattress, or having a stranger sleep in your house. It seemed like a really, really strange idea. They tried to launch it a couple of times. They tried to launch it south by southwest. It didn’t work, like three people used it. They tried to launch around the 2008 Presidential Conventions. The way they raised capital is actually, it’s kind of humorous because they couldn’t get anyone to give them money. They’d maxed out credit cards and they, basically because they were designers designed cereal boxes that were called ObamaO’s Hope in Every Bowl, and Captain McCain like a Maverick in Every Bite. Then they went and put cereal in it and they sold that. They raised twenty-five thousand dollars. That’s basically what kept this company afloat. Now it’s a ten billion dollar valuation on a startup. I mean it’s amazing what they’ve done. But it was a fringe idea. That’s one of the things you have to constantly be Scanning the Edges for what might be coming next. The third skill is what I’m calling Fly the OODA Loop. It stands for Observe, Orient, Decide, and Act. Are there any former military people in the room? Okay, have you heard of the OODA Loop? It’s an Air Force; it originally came from an Air Force Pilot named John Boyd. The legend is that John Boyd could shoot down any other fighter pilot in forty seconds or less. Across the Air Force it really became known as the OODA Loop. This is his secret. The way that you can defeat a competitor in real time in a fight is to Observe, Orient, Decide, and Act faster. If you can do that you change the landscape. You actually in a dog fight in a fighter jet, in a cockpit you change what’s happening. The other opponent is reacting to something that is now outdated. In the work place, in the business work place it’s the exact same thing. I think as every, as the landscape accelerates this become more and more important. What do you observe? Like what do you do? One thing that fighter pilots or entrepreneurs are looking for is a glitch, right. What doesn’t make sense? What do you actually pick up on? There’s academic research here of about tasks and awareness. Like you might think that something was odd. You might see something out of the corner of your eye and most of us just rationalize it away. We don’t think about it. We just sort of think, oh, okay that was weird. That was an anomaly. People who are you know creating and scaling ideas they jump on it, they like go for the glitch. They absolutely observe it and they do something about it. One of the things is you know how do you orient to it? You ask a ton of questions. You have certain metrics. Pete Thiel who is the PayPal co-founder and then Palantir, he’s the first money behind Facebook. He will say to orient as an investor at least he’ll look for technologies that are ten times better in a very, very narrow market. Like that’s counter intuitive because a lot of people are trying to go for these huge markets. They’re trying to pitch out like these ideas that would just change the world in huge ways. But instead what Peter Thiel orients to is like a very narrow deep market place that will have a ten times better technology. It’s important to think about how to orient as well. Then the Decide and the Act pieces are just fast. This is not the Hamlet, To Be or Not to Be. Nobody sits around and wonders what to do. They just make decisions and keep making more and more decisions. Then once you act it changes the landscape. The faster you do this the more effectively you combat any kind of a competitor and the landscape. This is Peter Thiel and Elon Musk. This is PayPal early on. PayPal was started, its two companies merging. It was Peter and Max Levchin that started and then they merged with x.com which is Elon’s company. The reason why PayPal’s a great example here is that they had that startup for eighteen months. Not a long period of time. They moved it through six models. They first thought, it was in nineteen ninety-nine. They first thought that they would beam; well they would have an encrypted technology for money. They would have a virtual wallet. Then they actually raised funding on beaming money between Palm Pilots. Like who here had a Palm? Okay, so some people had a Palm. Palm is not really around but PayPal is still around, right. They observed at one point that people were using the support site for trying to email money or whatever. They weren’t actually doing this beam between devices. That seemed very, very strange to them. They thought that seemed wrong. But then they very quickly oriented to it and jumped on it. They were like okay even though we raised money for that we’re going to try to do something with a website. Then they realized that eBay users were actually using PayPal and they didn’t want that. That was a bad, they thought, they were like go away eBay people you know your messing with our product. Then all of a sudden they oriented very quickly and acted on it because they realized that was a huge market. For everybody at that point of time who was sending a check in the mail, or whatever. It was like a very slow process. If you could use PayPal that would scale PayPal for them and they then were embedding their logos inside of eBay. There was all this kind of war going on with eBay. EBay was slow, so this is the competitor that didn’t react as quickly. They bought Billpoint another technology. Then they studied the market for twelve months. While they were studying the market these guys were like really, really quickly orienting to things and changing things up. They also had chargeback’s. Does anyone in here work with credit cards? Or know what a chargeback is? Yeah, so Max Levchin who’s the technology kind of wizard and founder on this, he saw a chargeback and he jumped right on it. Again, like there was no waiting around to try to wonder what that would be. A lot of the competitors got buried by money laundering and fraud. Max built a technology, he’s from the Ukraine. He built a technology that he called Igor because the Russians were hacking into this site and just like pilfering all the money out of him. It is today the squiggly line technology, the are you a human test you know to try to make sure that you’re a person and not a computer that’s trying to hack into anything. They all as individuals inside of PayPal were all flying the OODA Loop. They were doing it as a team. Then what comes out of it? The more interesting part, they sold PayPal when the tech bubble burst. It’s when I was at business school at Stanford as a student. It was doom and gloom. Everybody thought in 2000, 2001, 2002 that like technology in the Silicon Valley was done. These guys sold their company at that time. Then they went on to start YouTube and Yelp, and LinkedIn, Slide, Tesla Motors, Dig, their first money into Facebook, five hundred startups. I mean the outcome out of the PayPal Mafia as they’re called in Silicon Valley is extraordinary. When you talk to them like the Yelp founder Jeremy Stoppleman. When you talk to Jeremy he’ll say well he was a really young guy at PayPal. But what he learned was when something didn’t work to jump on the counter intuitive blip of data. Like Yelp was started as an email referral site and embedded in that they had like would you like to write a review? Jeremy was like nobody’s going to want to write a review. That a, and then he found out a lot of people liked writing reviews of like the drycleaner and the restaurant. Yelp became a review site. Or YouTube was originally a video dating site. I mean like that was what they that was going to be. Then they had a video of one of their founders at the zoo and this big elephant and whatever. They were just kind of hamming it up like clowning around. Everybody was watching the elephant video. They were like well that’s strange. But so they opened it up. Obviously YouTube is kind of got all kinds of videos on it. What they learned and if you know they all talk about it in slightly different ways. But one of the things they say is if you had worked in a place that was a really big place that you only learned about success and one way of doing it. You wouldn’t have struggled as much as they struggled. I mean they really almost, they had all these near death experiences at PayPal. But what they learned was that you could continue to iterate a model. You could continue to Observe, Orient, Decide, and Act. Then they could take it with them in the next things that did. That’s something that all of us can do. The fourth skill is what I’m calling Fail Wisely. This is different than from failing fast and failing forward. I think that’s the Web 2.0 thing. I think actually now from all the people that I interviewed they want to be imperfect. They will set a certain failure ratio. They’ll say twenty percent of the time I will get it wrong, or ten percent, or thirty percent. Or you know, but the ingoing assumption is that you will not have a perfect record here. You don’t want to actually be a four point student anymore. I think that business use to be about scaling up existing ideas, replicating and scaling, and taking things out into the world with a perfect record. Now given the landscape change and given how little we can actually predict. Now it’s about pushing the envelope and knowing that you’ll be wrong some of the time. But not failing catastrophically, like nobody wants to fail catastrophically here, right. Marshmallow Challenge, have you guys, has anyone seen this? Okay, a few people. This experiment was started in two thousand and seven. It’s been run with thousands of people actually internationally. Basically what it is is twenty sticks of spaghetti, one yard of tape, one yard of string, one marshmallow. You have twenty minutes in teams of four to build the largest freestanding structure that you can with the marshmallow on top. This was started actually out of Nokia. Then it was run all across different universities. Engineers and MBAs, and Fortune five hundreds, CEOs, and Architects, and all kinds of people have been put through the marshmallow challenge. Who do you think can build the tallest structure? Anyone? >>: Kindergarten kids. >> Amy Wilkinson: Yeah, yeah, there you go. These are the people who do the best job at it. They build structures at twenty-five inches tall. Engineers with Master’s Degrees build it on average twenty-four inches. The five year olds actually win. They, now the question is why is that, right? What I think is that they are able to Fail Wisely. They are the only group that rolls up their sleeves. They are not fearful. They just get right at it. They grab all the materials. They start right in. They’re the only group that asks for more of anyone of the materials. They ask for more spaghetti and more marshmallows. They just go for it. The worst performing group here is MBA students. The MBA students when you watch them sit around and plan. Right, they plan about what they’re going to do and who’s going to lead their team, and all of that. Then their time runs out. [laughter] It’s an example of just getting right in and trying to have a trial and error experimental approach. Setting a Failure Ratio, so these two guys are the founders of OPower, this company went public last year. They’re a great example. They conserve energy. They’re based out of Virginia. They started on the very premise of an experiment. They thought hey if we want to have people conserve how would we do that? They put door knockers on the handle, the doors of a number of homes in California saying please turn off your air conditioning in the summer and turn on your fan. You would be a good citizen. That would be a really good thing to do. We could conserve energy. Absolutely nobody did it. Nobody cared. Then they put a door knocker on the door that basically said, please turn off your air conditioning, please turn on your fan, you will save the planet. You know and absolutely nobody cared. Then they did a third experiment and they put these door knockers on people’s doors. They said, you know please turn off the air conditioning, turn on the fan; you will save fifty-five dollars on your bill. They figured, again nobody cared. No one did anything. Then they ran a fourth experiment and they put the door knockers on. They basically said, turn off your air conditioning, turn on your fan, seventy-seven percent of your neighbors are doing that, and that worked. It’s the peer pressure model of thinking that like the people in your neighborhood are conserving and you’re somehow like not keeping up with the Jones’ or whatever. That’s the basis of this entire model. They have been running the company. They now have done other experiments. This last summer they did a big one with the city of Baltimore on peak demands. Like could you get people to turn off their dishwasher during peak demands? They have conserved enough energy to power the City of Miami for a year. It’s an amazing model. But it is always small bets. It’s always these small experiments. They’re going to get it wrong some of the time. They also built a Facebook app. They thought like oh this is great we can get all social pressure going online. That did not work and they shut it back down. It actually has to be a report and you have to think that you might physically see your neighbors and not be doing as well in your actual physical neighborhood. But they’re an example of running now a pretty large company on this. So is the Stella & Dot founder. This is Jess Herrin. She was a co-founder of Wedding Channel.com. Now she is the founder of Stella & Dot. It’s a home based jewelry business. It’s like Mary Kay meets eBay, right. It’s scaled up to be about a three hundred million in revenue business. She basically with all of these products, those are her two little girls. She was an undergrad and an MBA with me. You know every single product that she’s putting out with other women stylists. They sell from home. They do a trunk show kind of model. They have Love it or Lose It. They’re always testing all of these little things. A certain percentage of her products just don’t ever make it into the market or they don’t, you know they don’t make very much success. But she’s constantly experimenting and constantly getting it wrong. If you talk to her it’s just as much about what she will learn and learn through. The fifth skill is what I’m calling Network Minds. The idea here is all about cognitive diversity. We talk about what we look like on the outside, right, gender, race, socioeconomic differences. My research basically informs the fact that it doesn’t matter that much. What matters is what your mind looks like on the inside. Then how will you bring your brain power to solve a problem? What will you do to get other brains to come and help you solve your problem? How can you network minds? This is an MRI machine. Who’s had an MRI? Okay, what is it like? Who can tell me what it’s like to have an MRI? >>: [inaudible] >> Amy Wilkinson: What? >>: It felt like it, claustrophobic. >>: Loud. >>: Claustrophobic. >>: Loud. >>: Claustrophobic. >>: It’s great when you have headphones with music on. [laughter] >> Amy Wilkinson: Okay, okay, so it’s loud, it’s claustrophobic. >>: It can be claustrophobic. >> Amy Wilkinson: Okay, so Doug Dietz is the designer of this for GE. He’s interviewed in the research as well. He’s a creator inside of a very large company. He was so proud of this technology and was in a hospital observing it, when a seven year old little girl came to have an MRI scan. As she came down the hallway with her parents holding her hands everything was fine until she saw this machine. Then she completely melted down. You know became hysterical and was crying, and scared, and everything else. It was a bad experience for her and her parents, and the lab techs. It just didn’t work. Doug Dietz then really felt like he had failed because it’s a beautiful piece of technology. But it really wasn’t working at all that day for that child. He went away and basically the data shows that eighty percent of children have to be sedated to take an MRI. Because they can’t stay still enough, it’s scary, it’s loud. They don’t totally understand why they’re there and what’s going on. What Doug did was go away and network minds. He tried to figure out like who he could get to talk to him about how they would redesign this. He went and got a bunch of people from the Children’s Museum. He got a bunch of people from daycare centers. He had a bunch of kids come in. He had parents come in. They all had these big sort of brainstorming sessions around how would you make this technology better for a kid? A lot of the kids started talking about going to camp or dressing up like their older sister. You know the people who designed children museums displays started talking about how to make it interactive and everything else. Basically what they came up with is this. [laughter] This is now an MRI there; it’s called the Adventure Series for kids. There are seven different themes. It’s the exact same technology. But when kids come to the hospital now they get like a backpack, they talk to a camp counselor, not a nurse. There’s music playing and music was mentioned. They get to, this is a nautical theme. But there’s that, there’s safari, there’s like a space theme. There’s all these different things. The sedation rate the amazing part is basically down to zero. By networking minds and getting all of these kinds of non-traditional players involved in figuring out how to make things better, that’s the result. This is David Kelley who is the founder of IDEO and the Stanford d.school. Stanford, so I’m going back to teach at Stanford Business School this spring. It’s not really publicly known, but Stanford’s putting a large portion of the endowment now behind the d.school, which is the Design School. It pulls from seven of the different graduate programs. To try to get people basically networking minds to solve problems in new ways. There are no degrees awarded. But it is just an unbelievably oversubscribed part of the university, for taking everybody in. The latest, when I was on campus the latest thing they were trying to solve is the TSA security thing. Like everybody hates TSA security and it’s a hassle for absolutely everybody. It’s a hassle for the workers. It’s a hassle for the travelers. You know it’s obviously very important because we want to have a secure situation going on. But they are looking at complex problems and putting you know an anthropologist with a neuroscientist, with an educator, with an MBA. Trying to figure out like how would we get problems solved in different ways. Then the last skill is what I’m calling Gift Small Goods. The idea here is that we, the small good would be a small favor or a small kindness. In the workplace it would be forwarding a resume or writing a few lines of code, or making an introduction for someone, critiquing a proposal. There are lots of small ways that we can help each other. It used to be the right thing to be a nice guy, right, in the work place and help your colleagues. Now in fact with the transparent economy and as quickly as word travels it’s a lot more productive. That’s the counter intuitive finding here is that nice guys or nice women who help each other out what that does is that sources, your reputation is amplified and proliferated. We know how you behave now. People then want to bring you information, and bring you opportunities and open doors for you. It makes you a lot more productive professional. This is Reid Hoffman the founder of LinkedIn. LinkedIn is founded on this very premise. The idea is if we are all transparently connected to each other. We know who’s worked with whom in the past just boss might be able to get information on an employee. But now like employees or anybody can get information about anybody else. It actually drives better behavior in the work place. Reid will say no one’s going to throw themselves in front of a train for you. It’s not like people are going to do these huge big favors. But if you have a whole lot of small favors and if you have exchange of small goods, that that is a much better workplace. It’s actually much better for your own reputation in getting things done for yourself. Then we’re back to bringing them all together. It’s really when all these things are combined that you know people are able to take an idea and take it to scale. It, the big point here about my research is really that it’s accessible to everyone. These are not; you don’t have to have a certain set of credentials. You don’t have to have an MBA. You don’t have to come with a lot of capital. You don’t actually have to have that much time. You can be learning and moving these things very quickly and in small steps. But it’s the combination of bringing them together that makes initiatives take off. That’s it and I would love questions. Yes? [applause] >>: How would you compare [indiscernible] the Twenty-First Century Think and Grow Rich? In terms of the author that actually went and interviewed at that time the same sort of entrepreneurial folks. Have you read that book? How would you [inaudible]? >> Amy Wilkinson: I haven’t read that book. >>: It might be interesting what you think. >> Amy Wilkinson: Yeah, I haven’t read that book. Simon and Schuster is my publisher. Simon and Schuster is bringing this book out at the Good to Great for people, if you know the Jim Collins Good to Great book. That looked at organizations, right, how do you take an organization up a level. This is all at the individual skill level. This is like how does an individual person do something that is you know taking their own leadership up a level. But I’ll look into the book, thank you. >>: Yeah, [indiscernible]. >> Amy Wilkinson: Yeah. >>: Do you start with twenty, thirty different skills and reduce it down to six, is that the process? >> Amy Wilkinson: Yeah, yes, so it’s grounded theory method which is sociology or a qualitative research methodology. There are ten thousand pages of transcripts here that were reviewed. You know five thousand pages of extra material, ten K’s, and ten Q’s, and annual data of various varieties, and four thousand pages of academic studies. This is a huge dataset. Then what you do with that is you start coding. You start looking for repeated concepts and repeated words. It’s a pattern recognition exercise across. Originally I thought there were forty, I mean like this is why it takes years to kind of do it. I thought there were forty-two things. Then I thought there were twenty some. Then I was down in the teens. These categories, so there’s six. It’s a new theory of six skills. But underneath each one of the six if you read in the chapters there’s three or four concepts in each one of the skills. Yeah, it’s a big you know kind of pattern recognition exercise. Yeah? >>: Is there a sequel about what not to do? [laughter] >> Amy Wilkinson: I don’t know. I mean maybe. I haven’t thought about that. I mean what to avoid? >>: Yeah or did you get, in your interviews for example. Did you get specific advice or examples of where somebody went wrong or where something was obviously either behavior problem, or some situation that you can also quotify about what not to do? >> Amy Wilkinson: Yeah, so I mean in the Fail Wisely chapter, so you don’t want to fail stupidly, right, if that’s what you’re asking. I mean, like meaning you don’t want to keep making the same mistake over and over, and over. That’s one thing that people talked about. >>: Let me say it differently. With all the startups you mentioned the stats are pretty bad for venture capital funded businesses that do well. It might be as interesting to look at what causes the thirty thousand failures for every success. >> Amy Wilkinson: Yes. [laughter] >>: It feels almost like looking at what not to do might be more actionable than looking at what to do, from a certain disposition. >> Amy Wilkinson: I think that’s, what? >>: I think I would [indiscernible] is right. Yes it’s good to look at that as part of the drill down. >>: But I was going to ask you, I don’t, I like what you put together, you’re pretty. >> Amy Wilkinson: I hear what you’re saying and I think that’s right. I mean seventy percent of venture capital is either a wash or not up, right so three of ten bets in the VC industry payoff. I went out very specifically to study the success stories. It’s hard to succeed, right. I mean the data actually shows that a lot of startups don’t make it or they don’t scale. In fact this dataset is you know one of the very largest on companies over a hundred million in revenue that have scaled in a short period of time. I think it’s more interesting to know why somebody succeeded and across all the industries, because that’s what we want to emulate. I think companies fail for many reasons. A few of them that were talked about when I interviewed people, they fail for internal team dynamics, right. If your internal team is fighting with itself and you see a lot of that. You see it with mergers of startups. You see it with teams that didn’t know each other before they started as a team. Those startups often don’t work. I think that’s the same in big companies. I mean I don’t think that that’s, but internal dynamics take teams down. Not learning a lesson, so failing at the same thing over and over and not trying something new, that was talked about. Like if you, you know a product could not work, a market could shift. But if just continue to stay after the same thing and you don’t actually, pivot is a word that a lot of people, I’m not wild about the word pivot. But if you don’t actually move off and do something different that’s a pretty bad thing to be stuck doing. But I don’t know. I mean I guess you could study all the failures. I don’t know why I would do that. I would much rather study the successes and then figure out how to emulate that. I think the commonalities are more interesting because I think the reasons for failure are a whole lot. You know it’s like, what is the famous quote, every happy family looks the same and every unhappy family has got some you know strange and different deviation to it. I’m after the happy families. [laughter] >>: I guess. >> Amy Wilkinson: Yeah? >>: Do you think kind of through the data that all six of those concepts you weight equally? I know you say they all have to come together. But do you, did you see that anything was more stronger or more prevalent than the others? >> Amy Wilkinson: They’re pretty much equal. I think that you have to find a Gap to begin with. The other thing to say about the model is you know it’s a sequential model. But you find a Gap often and then you Drive for Daylight. Like you say hey I found that thing and now I’m going to just really manage as fast as I can. Then you fly and OODA Loop, so you Observe, Orient, Decide, Act. You try to figure out to iterate it. Then inevitably you fail. Like, I mean like people are not having straight line careers. Like something is not working, right. Then they, people Network Minds. Like let me get some more brain power over here to try to help me out. Then Gifting Small Goods is something that just happens very, but I want to say specifically that it doesn’t, it’s not a line. This is not a checklist. I don’t want people to go away thinking oh I have a checklist of six things to do. Because these things work in concert, so you could fail and out of failing you could see an opportunity, right. I mean, so you could Fail Wisely and then spot a Gap, right. Or you could be Driving for Daylight and then be able to find something and be generous and Gifting a Small Good to somebody else. These things are happening sort of in concert. I do think people have to find a Gap. You have to spot an opportunity or you’re not in the game to begin with, right. I also think that people are failing all the time. Like every single person that I interviewed for this book talked about things that hadn’t gone right. I think those two if you know what was talked about most, those two are probably talked about most. Yeah? >> Amy Draves: I have a couple of online questions. One being, he was talking about small groups and how at Microsoft we work a lot of small groups work with each other. But you sort of addressed that a little bit. But he thought how do you drive this thinking beyond the person and target the immediate work, your immediate work group? How do you bring that entrepreneurial spirit to a team I suppose? >> Amy Wilkinson: Yeah, so, that’s a really good question because research is all on the individual level. But we’re all working with each other all the time, right. The PayPal guys are a great example. They and the fly the OODA Loop, like the wingman idea is you are flying with other people. You are working with other people in your team. Those dynamics, that chapter talks a little bit more about you know the obligation to dissent. I use to work at McKinsey, that’s actually one of the rules. You must dissent; if you disagree you actually have an obligation to speak up. That’s very much how the PayPal guys, you know they have fierce discussions. They, you know they disagree a lot with each other. But there’s a lot of respect for the intellectual capacity of each one of them. There’s a lot of respect. But there is not, consensus is actually seen as a bad thing a lot of the time. Because it means that somebody’s not thinking or somebody’s not coming up with a different angle on how you would crack a problem. I think you know this is an individual skill set. But I think it also takes in to consideration that the other people around you would be also like minded or kindred spirits in trying to be innovative and trying to be entrepreneurial. Then respecting there will be differences of opinion. There’s not going to be a real easy and fluid situation. It’s just not how the world works. Yeah? >>: For those successful creators that you interviewed. To what extent were they aware that they were practicing these skills? Like where they deliberately developing these skills or was it just kind of in their nature? >> Amy Wilkinson: They are fascinated by the research now because I went out and asked pretty open ended questions. This is kind of how you do it; you have a semi-structured interview schedule. You ask many of the same questions. But depending on the answers you let people talk about how their company worked or how their individual situation worked. They are not, I am not going to them and they are not saying to me I have six skills, right. Out of the research come the six skills. I would say they are pretty fascinated now to know what the other people are also doing. They’re calling me saying wow, you know I didn’t realize that I was like Elon Musk and I’m in Atlanta making you know Spanks, that’s cool. You know I think they’re all exhibiting these six skills. But they weren’t necessarily going out to do that. They were living their own lives. That’s one of the reasons to do the book to be honest. I feel like it’s the shortcut. Like I did the homework and I could hand somebody like hey these six things will actually really help you. It’s not a sure thing. I mean like there’s no sure thing on the fact that people will actually scale something that will really work. But the odds are a lot better if you do these six skills. Just because the recognition off of all these other successful people is that they have done these six skills. But they weren’t, yeah, they’re kind of also quite interested in what the results are. Because most entrepreneurials, most business people are operating. You know we’re all recreating the wheel. We’re like all trying to learn our own thing. Getting a research based piece of information that says these six things actually help I think is, hopefully it matter. I mean that would be reason I would go and try to do it, right. Yeah? >> Amy Draves: We have time for one more question. >>: I have two questions. [laughter] >>: Well, I’ll make it quick. I’ll be quick. The first question is in your book do you actually have the transcripts of the two hundred interviews? The second question is the six skills, can you tell us a little bit about maybe one or two skills that didn’t quite make the cut. But that you saw kind of a widespread among entrepreneurs you talked to? >> Amy Wilkinson: The two hundred interview transcripts are not in the book. They’re probably going to come out in various forms in articles and case studies, and other things like that. But the book is designed and this very intentional. The book is designed to take all of that nerdy research and try to make it a fast and fun read. The book is written narrative. It’s written so I hope people can read it in three or four hours. It’s one of these things where I think I spent five years of my life and like someone’s going to read on an airplane. Like okay, but it’s designed like that because I think that’s how people learn. I think we learn through stories. If you don’t make it a story based narrative concept people don’t grab it. The transcripts, yeah, I mean they will, I’m happy to send some to you if you want them. But this is the distilled version that’s a lot friendlier and hopefully faster, that’s that. Then on the second question about what didn’t make the cut? You know I think there’s a concept that I think quite a lot about that’s not really in the book, which is about how uncomfortable all these people are. That they actually get comfortable with being uncomfortable. I find that interesting. It’s kind of baked in there but not entirely. That is that there’s no striving for the corner office. There’s no like oh, I made it, you know. A lot of these people have been very, very successful, right. I mean financially successful. There’s a lot hero worship around entrepreneurs. But if you actually talk to them they’ll say oh gosh you know I don’t know if the next things going to work. I don’t know if this rockets going to land on the, you know there’s all these waves in the, I was just with Elon last week. He’s like, ah, we’re going to try this launch again in April. Then we’re going to try it again in June. You know a lot of people look at him and think; ah he’s just really made it. If you really talk to him he thinks like we’re going to just keep trying. I hope I live long enough to get this you know actually you know in a, he thinks he’s going to take life to Mars. I mean that’s like a crazy ambition, right. But I think that nobody is comfortable. That’s something I think we use to think that we would just have a job that would be a thirty year job, or we would have a corner office, or we would have made it at some point in time. The creators in this book are just always, the curiosity level never goes away. They’re always curiously exploring the next thing. Sometimes it’s going to work and sometimes it’s not going to work. I think that might not have come out as much as I would like it to. You can carry the message in the world for me. [laughter] >> Amy Draves: Thank you. >> Amy Wilkinson: Okay, yeah. [applause]