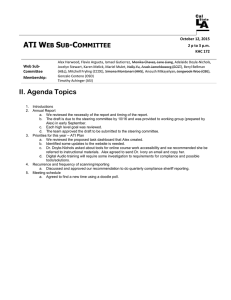

>> Jeff Jones: Okay. Thanks, everyone, for joining... from the Trustworthy Computing Group. I'm now in Corporate...

advertisement

>> Jeff Jones: Okay. Thanks, everyone, for joining me today. I'm Jeff Jones. I'm formerly from the Trustworthy Computing Group. I'm now in Corporate Communications, and I'm privileged today to introduce Charles Stross, and he's going to do a reading from two books, actually. One of them, the Annihilation Score. I assume actually everybody who's here has probably read him. But if not, I'll say a couple of things. I'm honored to do the introduction. I'm super-impressed with his imagination, extreme creativity, as well as the variety of his writing. So the first book I discovered was Singularity Sky. I've read the Merchant Princes, and I've read -- I'm going to confess, the first three books of the Laundry series, and I'm a little bit compulsive in that I have to read them in order, so I haven't started the latest one, but looking forward to it. So with that, I will turn it over to Charles. >> Charles Stross: Thank you very much indeed. Before I get started, can I ask for a brief show of hands, how many people here have read the Laundry Files, earlier books. Okay, so almost everybody knows what they're in for. A couple of words of introduction just in case, though. The first four of these books were sort of -- my agent didn't know how to sell them at first -humorous Lovecraftian spy thrillers about the IT industry? This made no sense to anybody. And to add to the confusion, the first four books were all tributes to different British spy thriller authors. I started with Len Deighton, then Ian Fleming and the Bond franchise, then moved onto a less well known one over here, but very highly respected, Anthony Price, then Peter O'Donnell, the author of Modesty Blaise. And then I sort of got bored with this after about 10 years and decided to start pastiching urban fantasy subgenres. If you're read my novella Equoid, which won the Hugo Award last year, that was unicorns with a life cycle, brainstormed with Peter Watts. Last year's novel, the Rhesus Chart, was opening sentence, don't be silly, Bob, said Mo, everybody knows vampires don't exist, which tells you everything you need to know about what that one was about. The Annihilation Score, which is the novel I'll be reading from first, is book six in the series. It's the first one narrated by a viewpoint character other than Bob. It's told by Mo, his wife of some years, big spoiler, now living apart, and it's also another theme one about an urban fantasy subgenre. This is the superhero novel. The elevator pitch for this one was Bob's exes form a superhero team and fight crime. There were a lot of committee meetings involved. And after that, if time permits, I'll be doing a little bit of a reading from the not-quitefinal draft of the Nightmare Stacks, which is book seven, which won't be out until next July. But first, a chunk of the Annihilation Score, and I'm going to start with the prologue. Please allow me to introduce myself. No. Strike that. Period stop backspace backspace bloody computer no stop that stop listening stop dictating end end oh I give up. Will you stop doing that? Start again, typing this time, damn speech recognition and auto-correct. My husband is sometimes a bit slow on the uptake. You'd think that after ten years together, of which we've been married for seven, he'd have realized that our relationship consisted of him, me and a bone-white violin made for a mad scientist by a luthier-turned-necromancer. But no. The third party in our menage turns out to be a surprise to him, and he needs more time to think about it. Bending over backwards to give him the benefit of the doubt, this has only become an issue since my husband acquired the ability to see Lecter -- that's what I call my violin when I argue with it -- for what he is. He. She. It. Whatever. Bob is very unusual in having this ability. It marks him as a member of a privileged elite, the select club of occult practitioners who can recognize when they're in the presence of and stand fast against it rather than fleeing screaming into the night, like the vampire bitch from Human Resources, and what was she doing in the living room at five o'clock in the morning -- issues. Vampires, violins, and marital miscommunications. I've gone off-topic again, haven't I? Take three. Hello. My name is Mo. That's short for Dominique O'Brien. I'm 43 years old, married to a man who calls himself Bob Howard, aged 38 and a quarter. We are currently separated while we try to sort things out -- things including, but not limited to, my relationship with my violin, his relationship with the vampire bitch from Human Resources and the end of the world as we know it, which is an ongoing work-related headache. You are reading this because you are presumably a new Laundry fish, and I'm not on hand to brief you in person. Yes, I'm writing this under my own name. None of those silly code names that my other half is so keen on. If I were him, you'd probably be reading a work journal by “Sabine Braveheart” or some such nonsense, I'm not, so let's keep this simple. It's quite likely I'll be dead by the time you read this report, or I might just be on extended medical leave. We're required to keep these journals in order to facilitate institutional knowledge retention in event of our demise, but frankly, DIY psychotherapy is so much of a higher priority right now. I've been under extreme stress recently, but unfortunately, a nervous breakdown is a luxury I can't afford. There's no time for it in the calendar. So I'm working it all out as I go along, and if you can get past all the Bridget Jones meets the apocalypse stuff, you might also pick up some useful workplace tips. Bob and I are both operatives. We work for an obscure department of the British civil service, known to its inmates -- of whom you are now one -- as the Laundry. Bob works in IT, while I have a part-time consultancy post and also teach theory and philosophy of music at Birkbeck College. In actual fact, Bob is a computational demonologist turned necromancer, and I am a combat epistemologist. It's my job to study hostile philosophies and disrupt them. Don't ask. It'll all become clear later. I also play the violin. A brief recap -- magic is the name given to the practice of manipulating the ultrastructure of reality by carrying out mathematical operations. We live in a multiverse, and certain operators trigger echoes in the Platonic realm of mathematical truth, echoes which can be amplified and feed back into our and other realities. Computers, being machines for executing mathematical operations at very high speed, are useful to us as occult engines. Likewise, some of us have the ability to carry out magical operations in our own heads, albeit at terrible cost. Magic used to be rare and difficult and unsystematized. It became rather more common and easy and formal after Alan Turing put it on a sound theoretical footing at Bletchley Park during the war, for which sin our predecessors had him bumped off during the 1950s. It was an act of epic stupidity that we're deeply ashamed, and subsequently, people discover the core theorems for themselves tend to be recruited and put to use by the organization, instead. Unfortunately, computers are everywhere these days, and so are hackers, to such an extent that we have a serious human resources problem, as in, too many people to keep track of. Worse, there are not only too many computers, but too many brains. The effect of all this thinking on the structure of spacetime is damaging -- the more magic there is, the easier magic becomes, and the risk we run is that the increasing rate of thaumatergical flux over time tends to infinity and we hit the magical singularity, and spacetime breaks down, and the nightmares known as the Elder Gods come out to play. We in the Laundry refer to this apocalyptic situation as Case Nightmare Green. The bad news is, due to the population crisis, we've been in its early stages for the past few years, and we're unlikely to be safe again until the 22nd century. And so it is we live a curious double life, as boring, middle-aged civil servants on the one hand and as the nation's occult security service on the other, which brings me to the subject of Operation Incorrigible. I'm supposed to be using this document to give you a full and frank account of Operation Incorrigible. I suppose it is a decent introduction to what we do here in the Laundry. The trouble is, my experience of it was colored by certain events of a personal nature, and although I recognize that it is highly unprofessional to bring one's private life into the office, not to mention potentially offensive and a violation of HR guidelines on respect for diversity and sexual misconduct, I can't let it pass. Bluntly, Bob started it, and I really can't see any way to explain Operation Incorrigible without reference to the vampire bitch from HR and worse, her with the gills, or the mayor of London, the nude sculpture on the fourth plinth and how I blew my cover, not to mention a plague of superheroes, what it's like to have to set up a government agency from scratch during a crisis, and the truth about the official Home Office superhero team. And finally, my relationship with Professor Freudstein. So, Bob? Bob, I know you're reading this. You'd better tell Relate we need a marriage counselor with a security clearance, because this is what happened. And I'm now going to skip forward a couple of chapters and several very, very bad days indeed. An hour before my alarm call, at about 10 to 11:00, my ears register the distant ringing of the work telephone in the kitchen. It takes me 11 rings, six more than usual, to get to the phone, and I pick it up bleary-eyed and panting. Yes? I gasp, certain that something is wrong. Then I realize what it is. Bob would normally have answered the phone because he sleeps on the side of the bed nearest the door. Ops desk. Is that Agent Candid? This is two calls in 12 hours. Yes, I admit, and authenticate myself. What is it? Sorry to bother you after last night, but we have a -- the duty officer sounds reticent, which is just plain wrong. We have a peculiar situation emerging. How soon can you get to Trafalgar Square with your instrument? What for? We want you to busk. Flummoxed is my middle name. You want me to busk why, precisely, in Trafalgar Square? Don't you need a license? Oh, the police will cover for you. It would be best if you looked casual, a mature student out having fun, something like that. I don't know how to explain to the duty officer that most music students aren't in their early 40s. Maybe I just look young for my age. I sigh. I'll give it a try. What's the plan? There's a developing situation on the Fourth Plinth, and we need someone to keep an eye on it who isn't going to draw attention and who's equipped to intervene if it escalates. All our reserves are committed to mopping up after last night. Something really bad happens at the end of the Rhesus Chart, and this is the night after. So I know this sounds bad, but when I say we're scraping the barrel, I mean, we're totally overcommitted and running at 120%, but we didn't want to disturb you, and there's no one else. Suddenly, it clicks. You want me because I'm socially invisible, don't you? You could put it like that way. Personally, I'd rather not, but Colonel Lockhart said you'd understand. He ends on a whimper, blue shifting into a whine, and so he should. The landline phone is a 1940s-era Bakelite and steel monstrosity. Otherwise, my death grip would be crumbling it to splinters at this point. I'll be there in an hour, I snarl as politely as I can, and slam the receiver down so hard that it bounces. The Laundry is regrettably top heavy with men of a certain age. Institutional culture propagates down the decades, and however much we try to change it, it grinds you down after a while. As it happens, the Laundry is a lot better today than it was when I was sucked into the machinery a decade ago, but it takes an entire working career to climb up the promotion ladder, and as with all organizations, shit trickles down from the top. In this particular case, I'm forced to admit that Lockhart has a good and valid point. Women over about 40 become socially invisible, and I'm close enough to the tipping point that if I don't take care of my appearance, I can fall foul of it. It's a very strange experience, being the invisible woman. You can walk into a shop or restaurant or a bar, and eyeballs just slide past you as if you aren't there. When you're trying to get served, it's infuriating at best, and sometimes humiliating, but in our line of work, sometimes, having a passive cloak of invisibility that doesn't set off every detector within a kilometer can be useful. I grumble to myself as I refill the cat's bowl, retrieve my instrument, run a brush through my hair and hunt out casualwear I'd ordinarily have relegated to housework only days. I pick out jeans, a cable knit sweater, what used to be a nice flying jacket of Bob's, a comfy but warm pair of Doc Martens, and by way of accessories, a liberty scarf and a black beret that have both seen better days. Yeah, that's my boho mature student persona, baby. For a moment, I contemplate going hipster instead, but that might stand out. A smear of lipstick and a battered leather handbag complete the ensemble, and I'm ready to serenade the one-legged pigeons of London. Skip forward a little bit. The taxi drops me precisely outside the entrance to Charing Cross tube station. I head towards the confused mass of pedestrian crossings on the strand, and it takes me a couple of minutes to make it to the edge of Trafalgar Square, where I pause beneath the supercilious gaze of a one-eyed admiral, mentally dragged my middle-aged invisibility cloak tight around my shoulders and take stock of my surroundings. In the middle of the square, fountains fronted by Nelson's Column. At each corner of the square, there's a plinth. Three of the plinths are surmounted by pompous Victorian triumphalist statues, General Sir Harry Javerlock, General Sir Charles James Napier, and His Nobby Nob-ness, King George the Fourth, himself. But over to the left at the back is the infamous empty Fourth Plinth, and the instance I clap eyes on it, I realize that we have a problem. The Fourth Plinth is one of those eccentric British affectations which we love to parade around in public as a sign of our broad-minded tolerance. It's actually just another classical stone plinth, originally intended to support an equestrian statue, but it's been empty for 150 years because nobody could agree who to put on it. Then, around the turn of the millennium, the Royal Society of Arts said, oi, can we borrow the plinth? And ever since then, it's been occupied by an ever-changing succession of arts projects, sometimes a statue, sometimes an abstract sculpture, sometimes a random member of the public reciting poetry or narrating Shakespeare in semaphore. I'm not making that last one up. Today, there appears to be a human pyramid on the plinth. Well, maybe it's a rugby scrum or a public orgy or a sponsored die in. I'm not sure, because I'm at the other side of the square, and there are a lot of people in the way. But there's what looks like a pile of naked human bodies up there, with the odd leg or arm flopping limply over the side. I sit on one of the steps and open my violin case. Pigeons rattle and flap their way across the flagstones, but I force myself not to let them distract me. On the far side of the square, I spot a van with a satellite uplink dish on its roof and an open door, a journalist with cameramen in tow. They seem to be looking up at the plinth. I take Lecter and his bow out, latch the case closed and sling it on my back. Standing with my violin in hand, I look for the police. There's always a car or two drawn up around the edge of the square, but today, I spot three vans and four cars, one with the markings of an armed response vehicle. They're all parked on the west side of the square, and a handful of bobbies in stabbles are dispersed among the crowd, which is no thinner or thicker than I'd expect for a weekday in one of the nation's most prominent tourist attractions. No sign of anything particularly unusual, though, except, whoa. I'm so started by what I see that I speak aloud, but nobody pays me any attention, because everyone else is doing it, too. A woman floats into the air in front of the plinth. She's a yummy-mummy type, modishly dressed with a matchingly accessorized baby and a buggy the size of a Range Rover. She's waving her arms and her legs like an upside-down beetle, clinging onto the pushchair, which is also airborne, for grim death. I can just about hear her desperate screams for help above the traffic noise and the hum of the crowd as she levitates alongside the four-meter-tall slab of marble. The pushchair tips sideways and sheds its load. A rain of baby bottles and diapers splat to the ground. The woman screams again and loses her grip on the buggy. It drops for a moment, then swoops and kisses the ground in a controlled landing. She, however, is not so lucky. Whatever force holds her airborne raises her higher, then slides her above the pile of bodies on the plinth. Then, invisible hands start to undress her in midair. I look around. A couple of the police are dotted around the plinth, but they seem reluctant to approach it. Looking harder, I see they're putting down cones and unrolling incident tape. The woman is naked now. Suddenly, she stops thrashing, as if paralyzed or stunned. Her invisible assailant floats her slowly over the plinth, then lowers her on top of the mound of bodies that are already there. I desperately hope she's not dead. I begin to walk towards the middle of the square. Sorry, Miss, you can't go there. I stop. There's not much point in trying to walk right through a two-meter-tall slab of London's finest who's just stepped in front of you, but looking past his shoulder, I see another couple of vans pulling up, cops in riot gear climbing out and forming a line facing outwards against the plinth. I pull out my warrant card and hold it where he can't ignore it. Take me to your incident controller. Right. Skip forward again. A big navy blue mobile command post is parking just around the corner in Pall Mall, and my guide points me at it. I get to the bus just as a knot of police officers converges on it. A short woman with a no-nonsense attitude is giving them marching orders. I'm about to raise my warrant card again when she turns and stares at me, and I recognize her. Oh, good, says Josephine. Is this your mess? It's Inspector Jo Sullivan. I don't know. I just got here. I shrug, bow and fiddle in either hand. I feel calmer now that I've got a professional to work with. I got a call an hour ago. When did it kick off? Wait. She turns to her posse. Peeps, this is Dr. O'Brien. She works with us. Give her what she asks for. Any questions, bring them to me. Now, get moving. If I was the praying kind, I'd think my wishes were answered. Jo Sullivan is one of our direct contacts with the metropolitan police. She'd worked with us on and off for longer than I've been doing fieldwork. She turns back to me. Started 78 minutes ago. Body one goes flying up to situationist art-show heaven. Australian backpacker, mid-20s. Infrared camera on the chopper says they're still warm and breathing, but they're not moving it, and whatever's doing it likes its bananas peeled. She glances at her tablet. We're up to 12 bodies now, but nobody has any idea what's doing it. We sent up the bat-signal for Officer Friendly, but he's not answering. Officer Friendly? One of ours. He's with the Association of Chief Police Officers, but they're stretched too thin. He's probably still tangled up in paperwork and witness statements from his last callout. Her frustration is palpable. I don't want to have to cordon off Trafalgar Square, but if we can't find the perp, well -- well, I say, let me see if the office knows anything. We're standing next to a van with open doors, so I park my violin on the front seat while I pull out the phone. Duty desk? O'Brien here. Can you put me through to whatever idiot thought it was a good idea to send me over to Trafalgar Square without a briefing. Yes, Dr. O'Brien. Transferring you now. Good morning, Mo. I recognize Gerry Lockhart's gravelly voice immediately. What's going on? I resist the urge to roll my eyes. We have a major incident in Trafalgar Square and you're asking me? Someone is stripping tourists naked and building a pile on the Fourth Plinth, paralyzing them, too. The police have no idea, and they're on the edge of -shouting distracts me. I hunch my head over to hold my phone against my shoulder and turn to see what's going on. Oh, dear. It just escalated. I'll call you back. Another body is floating upwards. He's hanging onto his bicycle by the handlebars, legs pedaling furiously in midair. Portly, his suit rumpled and his mass of unkempt blond hair flopping across his forehead, he's instantly recognizable as the mayor of London. This is the point where I know it's an American audience here, because the Brits would have been rolling on the floor a minute ago. Oh, dear fucking Christ on a crutch, mouths Josephine, her eyes round with horror. I wince in sympathy. Get him, she shouts. Cops were already converging on the levitating mayor like a pack of hounds in pursuit of a fox, the unspeakable in pursuit of the uneatable. He floats above them, calling for help. One of them jumps high enough to grab the front wheel of the bike, but dangles for barely a second before it slips from the mayor's grip. He lands with a crash, and the mayor floats higher. I ring off, then fumble through the phone's confusing mass of icons until I get to the OFCUT suite, occult sensors and countermeasures. Yes, we do indeed have an app for that. I raise the phone and slowly pan it across the square. The mayor's struggles are aligned in green, the contours of the form field outlined by the phone's modified camera chip. The bodies atop the plinth also glow. Gotcha, I think. I tap Josephine's shoulder to get her attention, and she whirls. Yes? she demands. Don't be too obvious about it, I say, keeping my voice quiet and conversational, but our merry prankster is chilling out on the northeast plinth between the legs of a horse. He's lit up like a laser, backlit emerald in my phone's display, but when I try to look at him with my own eyes, they just don't seem to want to see him. It's far too easy to focus on the horse's head or the stone plinth beneath it. He's got some kind of don't-look-at-me field. Shimmering green contrails link his swooping hands to the body of the current victim. Josephine grins savagely. Charming. I'll have my boys lift him. No. I slide my phone back into my jacket pocket, then collect the violin. We have no idea of his full capabilities. So far, he's given us telekinesis, paralysis and observation avoidance. That's quite a hat trick, isn't it? But we don't know that it's all he's capable of, and there's his victims to think about. If we take him down, does the paralysis suddenly wear off? If so, they're lying naked on a platform four meters up, over stone flags. Someone is going to fall and break their neck if they start moving. And then there's the motivation issue to consider. So I pause. Do you have any ideas? Above the plinth, the mayor of London is twirling around his long axis like a chicken on a rotisserie. His coat has taken flight and is flapping around the top of Nelson's Column like a demented raven. His shoes pop off like champagne corks as our prankster debags the old Etonian. Beneath him, that damned TV camera is presumably getting the lead item for tonight's news. Public safety comes first. Then I need to get a couple of squads ready to rush in with air bags, Josephine decides. Someone to disable him on my word. She looks at me, then takes a deep breath and looks back at the mayor. Can you distract him? I look around the square. I'll do my best. Give me a minute to report in, and then I'll make a song and dance under his nose, starting in -- I check my watch -- five minutes? Go. She pats me on the back, then hands back to the mobile incident room. I walk across the crowded plaza, gaze downcast to avoid making eye contact with the people I'm carefully avoiding. The police are clearing the northwest corner of the square by forming a line, elbow to elbow, and expanding it. Josephine has obviously told them to keep it low key and friendly, because there's a marked lack of jostling and riot shields. They're having to work at it, though, because if there's one thing guaranteed to attract the attention of tourists and locals alike, it's the spectacle of a levitating semi-naked mayor. The square is stippled with the flicker of camera fill-in flashes. I have to shimmy to avoid elbows and backpacks and oblivious nonnatives stopping dead to peer at their tourist guides. My line of sight on George the Fourth is tenuous, and in any case, I can't be too obvious about keeping an eye on him. Rather than heading direct to the invisible joker, I stroll in a wide curve around the outside of the square, violin at my shoulder and bow poised. Finally, I find a reasonable pitch. It's nothing special, just a patch of flagstones aside a low wall that isn't already occupied by a tour group or another musical hopeful. But it's about 50 meters away from George and his unseen passenger, and I've go at sight line on the police presence around the plinth and, beyond it, the mobile incident vehicle. I unsling the violin case and lay it open at my feet. Then I flex my fingers. Lecter is sleepy and reluctant to rise to full awareness, which is good. When he's in this state, he's little more than a regular instrument. I check the pickups and switch off the small pre-amp. What are you doing? I ignore him and start to tune up. I check my watch. It's time. I launch into the Ciaccona from Bach's Partita in D minor, because I can do it in my sleep while reserving 90% of my attention to keeping track of developments, and more importantly, Lecter is used to me using it as a basic exercise, rather than the prelude to an attack. What are you doing? he whines in my head. I let him see the statue through my eyes, complete with a disturbing blind spot between the front legs of the horse. Ah. This is a violin made out of bits of human bone extracted while the owners were still screaming. It's not a very nice instrument. I turn slowly to gaze in the direction of the plinth. The mayor twirls slowly, stripped down to a pair of polka-dotted navy boxer shorts. As I watch, they begin to slide south. He grabs at them, and for a moment, he keeps his grip, but then the fabric tears and they fly away. Oh my, I mouth, nearly losing my fingering as the spangle and flicker of camera flashes rises to a manic intensity. He's going to be on the front page of all the newspapers tomorrow. And I turn back towards my target. Lend me your vision, I instruct Lecter as I stare across the bridge of the instrument. My sight grays out for a moment and then returns. Some colors are emphasized. There's a strange lambency to the air between the horse's hooves, which slowly resolves into the shape of a seated human figure. Can I eat him, asks my violin. No, I convey through the tension of my fingertips. Mine. Not yours. Lecter whines, I'm hungry. Nevertheless, I tighten my grip and draw on the violin's power. Bach, I decide, is inappropriate. This calls for something more contemporary, something darker. I segue into a different form, a more rhythmic, sinister melody wrapped around an implicit beat, Bela Lugosi's Dead, for solo improv values of mortality. I relax my grip on Lecter's appetite, and he strings forward eagerly, sucking on the energy source in front of him. The blind spot twitches slightly, then begins to shrink. Arms and legs slide into view. Hands move, agitated. Laughing Boy has realized that something is wrong. Out of the corner of my eye, I spot the mayor standing on top of a pile of naked bodies on the plinth. He's waving and gesticulating in my direction. Is he a sensitive? Shit. Nothing to be done. I press on. Raising the bow for a second, I flip the switch on the violin's pre-amp. It's not an audio amplifier, and those aren't electronic pickups. I started subtle, but now it's time to party. The bats have left the belfry, and I'm almost airborne. Whoops. My ward buzzes angrily, and I hastily squirt juice into it, mojo sucked out of the joker on the plinth who's taken aim at me. I land with a painful jolt but manage to absorb the drop with my knees. I'll feel it tomorrow. Rooted to the ground again, I increase both volume and tempo, whirling into a screaming blur as the song rises. The strings begin to glow, and now I reach out with Lecter's power and wrap my will around the target. Got you. He struggles as I lift him into the air, stabbing at me with pulses of near-solid air that would rupture eardrums and break bones if I didn't have a defensive ward, drawing on the near-infinite depths of the violin's power. He screams obscenities and lashes out at me. For a moment, I think I've caught a giant frog. Then I realize he's just plump. Beer guts and Lycra body stockings really don't play well together. Put me down, you motherfucking hippie bitch. Put me down or I will fuck you up so hard you'll walk bow-legged for a month. I tighten my grip on him and he shuts up, unable to draw breath. I see red, literally, heart pounding and head throbbing in time to the beat I'm imagining. Laughing Boy likes to strip the clothes off young women in public as he adds them to the pornographic sculpture he's building on the empty plinth. Laughing Boy thinks rape jokes are funny. Laughing Boy thinks it's all fun and games until a motherfucking hippie bitch turns his own mojo back on him, does he? I'll show him. I'll squeeze him until his guts explode. Stop that, I tell Lecter. Laughing Boy is turning blue in the face, eyes bulging as I dangle him above the heads of the crowd. I let him down gently, in the middle of a knot of riot police, then stop the music dead and lower my instrument, feeling sick. Oh God oh God oh God, I mumble. The residual power surge warms the protective ward at the base of my throat. I nearly throw up. I just nearly hanged a man with a noose of air. What's happening to me? I put my instrument away and pick up its case and begin to walk towards the mobile incident command vehicle. And that's when I see the second TV uplink van, with a BBC news crew and the camera tracking me for my reaction shot, when I realize they broadcast they entire magical duel live on News 24. So much for secret agents. And now, let me just see if I can pull this up. Okay. With you in a second for a surprise extract from next year's Laundry Files novel, the Nightmare Stacks. Just a second while I resize it slightly for easier reading. A word of introduction. This is not a novel told by Bob or by Mo. This one is about Alex, the somewhat nerdy banking IT person introduced in the Rhesus Chart. People here read the Rhesus Chart? Yes. I'm taking a trip around various other Laundry Files protagonists, although the next Bob novel will be book eight, the Delirium Brief, which I'm sort of working on in the background for the year after next. Meanwhile, though, here is the Nightmare Stacks, which is another urban fantasy pastiche, this one dealing with elves, but not in a good way. So I'll just read the introduction. A vampire is haunting Whitby. It's traditional. It's an hour after dusk on a Saturday evening, four weeks before the spring Gothic festival. Alex the vampire strolls along the seafront, his hands thrust deep into the pockets of his tweed jacket. There's a chill breeze blowing onshore, and he has the pavement to himself as he walks, eyes downcast and chin tucked into his chest, lost in thought. What profound insight does a creature of the night contemplate as he paces along the north promenade beside the beach, opposite a row of moonlit houses? What ancient wisdom? What hideous secrets haunt the conscious of the undying. Let's take a look inside his head. Alex is fretting about his Form P764 employee travel and subsistence claim, which he will have to fill out once he returns to his crammed room in a local bed and breakfast. He looks as large and sinister in his mind's eye as a vision of his own lichenstained gravestone. Nevertheless, it provides a welcome distraction from the Eldritch undead horror that is his student loan company statement. And that in turn pales into insignificance compared to the worst dread of all, how he is going to explain everything that has happened in the past few months to his parents, or at least those bits that aren't classified government secrets. Alex hasn't been a vampire for very long, and he isn't very good at it yet. But at least he's still alive, unlike several other members of his brood. The sea is coming in, and with it, the clouds. The wind is chilly on his skin, and so Alex turns and begins to retrace his steps towards -- stairs up to the High Street, past the pavilion and the whalebone arch, past shuttered cafes and the museum. He walks up the path to the cliffside, wondering if he's made a mistake. He's not sure, if he's honest with himself, that coming to Whitby was the right thing to do. He's supposed to be in Leeds, where he'll be working for the next few weeks. Someone booked him a seat on a Friday afternoon train, the better to enable him to make it to the office at 9:00 sharp on Monday. They obviously haven't got the memo about flextime hours in persons of hemophagy. Spending the weekend in Whitby was entirely his own idea. He's never visited the small coastal village before. Indeed, he only knows about it two reasons. Whitby is famous from the novel Dracula as the harbor where the ghost ship Demeter comes aground, and more recently, it plays host to a number of Goth festivals, themselves attracted to the village because of its famous fang-infested foreshore. Why Whitby, if not because of the obvious cliche, for Alex is not a Goth? Well, Whitby has one other advantage. It's not close enough to his home city that there's any risk of him running into his parents or younger sister by accident. Whitby is Alex's excuse for not being in Leeds while he's not working, and not being in Leeds is his excuse for not visiting his family, and not visiting his family makes it a whole lot easier not to tell them about the V-word, which is an awkwardness he's been grappling with in ever-increasing discomfort for months now, like a zit that stubbornly refuses to burst. The season for Goths and their steampunk siblings may not be here yet, but Whitby isn't entirely devoid of a flagrantly historical. As it happens, there's a group of drama students staying in one of the B&Bs on the High Street, and as he's passing the door, it bursts open. Alex suddenly finds himself adrift in a sea of Mina Harkers and Abraham Van Helsings, a trio of diaphanously clad Brides of Dracula eddying around him. They giggle and laugh at some private joke as they swish past, bringing a flush to Alex's cheeks. Alex has a bad case of wandering male gaze, a side effect of his monastic upbringing and being about 24 years old. He's mature enough to find this mortifying, but not sufficiently strong willed to suppress it in the presence of so much well-displayed cleavage. I say. Alex skids to a stop, just in time to avoid colliding with a fellow in white tie and tails, his red satin-lined opera cape draped across his shoulders. I say, old man -- the fellow doffs his top hat with white gloves that glimmer theatrically in the darkness. Obnoxiously dedicated to staying in character, he exudes the passive-aggressive politeness and assured self-confidence that suggest it is Alex, and not he, who is intent in occupying the wrong century. Alex fights hard not to take an instant dislike to him as he continues. I don't think I've seen you before. Who are you supposed to be? Alex does a double take. He's not wearing a costume, but in the darkness, his tweed jacket and opennecked white shirt, worn with a scarf against the late March chill, evidently resembles a period item. An imp of the mildly perverse whispers in his ear. Quincey Morris, he tells the amateur Dracula, feeling slightly smug about knowing his Stoker, although in truth he just skimmed the Wikipedia plot synopsis on the train over. Capital, chortles the fellow, and I am Sir Arthur Holmwood, so I suppose that makes us rivals in love for the hand of a delectable Lucy. A twitch of his chiseled chin indicates a robustly athletic student doing her best to portray a consumptive Victorian beauty, not one of the now-shivering brides, at least until the fiend snatches her away, haha. Ah, right. Come on, there's no time to lose. We received a report by telegraph, he adds confidingly, that the fiend has been sighted up by the graveyard. We'd better head straight there. Is Jeremy always this much of a ham, the first Bride of Dracula, verdigris hair and a nose ring, wearing a pinstriped bustle dress and a necklace of paste gems the size of quail eggs whispers in the direction of a second straight-haired blonde, clad in a crimson corset and several yards of tulle. It's not meant to carry, but Alex, with a vampire's preternatural hearing, can't help listening in. Not usually. He was hitting the Red Bull and vodka pretty hard, Bride 2 observes, then grimaces and adjusts her fangs. He usually mellows out once he gets his groove. Follow me, declares the bumptious Arthur Holmwood, gesturing theatrically as he strides purposefully up the cliffside path. Are you coming, Bride 1 asks Alex brightly? I suppose. Alex checks his priorities and rapidly realizes that the alternative to a torrid date with his Form P764 -- oh, yes, of course. But I don't suppose you'd mind lending me your jacket. It's Baltic, this evening. As they sashay towards the cliff, Alex confesses, even as he strips off his jacket, I'm not a LARPer, really. I hope you don't mind. Nah, that's cool. We're just doing a dress rehearsal tonight. The green-haired girl pulls his tweed jacket on over her bare shoulders. Alex extends his elbow, feeling a rare fit of gratitude to his sister Sarah for having hijacked the living room telly for one too many Regency costume dramas in years gone by, and she takes his arm. I'm Cassie. Who are you? Alex. Alex feels himself carried along, out of control, as if he's indeed been abducted by the alien and seductive brides of Dracula. He's not totally unsocialized, but he's the product of a single-sex schooling, followed by graduate and postgraduate studies in a field with institutionalized gender bias. When you subject a statistically significant sample size of otherworldly male nerds to this treatment, what you end up with is a certain proportion of 24year-old virgins. It therefore takes Alex a moment to remember that most people would deal with the current situation by making friendly conversation rather than wigging out. You're researching for a performance of Dracula for the festival, he eventually manages. Yes, yes, it's a walking performance. Cassie leans on his arm as they pick their way up the steepening incline. Her hand is warm. Me, Veronica and Louise are the brides. Behind the burbly front, she sounds slightly distant, as if rehearsing every sentence inside her own head before she speaks. In the background, Veronica murmurs something inaudible around her fangs. There's a confrontation in the park, a fight scene in the graveyard. Then, we pursue the Count to the ruins of the abbey for the big climax. It's the whole vampire thing, very dramatic, very sexy. What brings you to town? Alex spots her studying him sidelong, and his guts clench as he realizes that she knows he isn't, in fact, in steampunk drag or here for the Goth weekend experience. He's just woefully unfashionable. I'm -- Alex's brain freezes as he remembers the fearful oath the smiling man in the blue uniform made him swear as he assigned the official Secrets Act using a calligraphy pen loaded with his own blood, that requires him to act in accordance with his perception of the organization's best interest. I'm a mathematician. I work for the government. Nerd out, fool, his socially adept superego swears, despairingly. That's funny. Cassie stares at him. You're too shot to be Alan Turing. She means Benedict Cumberbatch, in the movie. You mean the GCHQ, right? The spooks? Again, that subtle pause in her speech, as if she's reading from an internal script. Oh, no, I don't work for GCHQ, Alex says hastily, mortified. No, it's much more boring than that, which is what he has to say to the smoking-hot girl on his arm, because if he tells her the truth, his new superiors will be extremely disappointed in him, with consequences which might be merely embarrassing, but which could potentially be fatal. No, really, I'm just here for the weekend, getting away from Leeds, because that's where work sent me. A thought strikes him. Do you really think I look like Alan Turing? But they've reached the top of a hill and are nearly at the park as he asks, and Cassie releases his arm. Hey, Ronnie, they're already here. We're late. She turns to him. I'm really sorry, but we're on in 60 seconds, and I've got to get in character, and I don't have time. She slides out of his jacket, and while he's fumbling with it, she opens a tiny clutch and pulls out a pair of plastic fangs. Sorry about this. Stick around for the after party? Oh, yes, says Alex. Cassie nods. Then she and the other two Brides of Dracula, turn, raise their arms and proceed to writhe languorously, for Jeremy's not the only ham here, towards a small clump of mostly black-clad onlookers in the middle of the park's nearly manicured lawn. He watches Cassie's enchanting back receding. He is moonstruck for all of 30 seconds. Then his phone begins to play Ride of the Valkyries. What? Alex pulls out his phone and sees a most unwelcome caller ID. It's Head Office. Hello, Alex speaking. I mean, Dr. Schwartz here. Who's this? There's a brief pause. Please hold. Another voice comes on the line, male, older, weary. Doctor, this is the DM speaking. Oh, fuck, the DM? Alex has heard of a semi-legendary reclusive dungeon master. He was covered in one of the Friday miscellaneous sessions last month, briefing someone in external assets has laid on for the surviving members of the vampire scrum, to bring them up to speed on some of their new coworkers. He racks his brain desperately, trying to remember what it is that the DM does for the Laundry. Something to do with running a very peculiar Dungeons and Dragons campaign, or was it working with iterated game theory and Turing complete rule sets in production systems based on applied demonology. Alex squelches the thought before it trails off into the mists of memory. What can I do for you, he asks. According to the duty officer, you're in Whitby. Are you in Whitby, Dr. Schwartz? If so, what are you doing there? I was just chatting up the Brides of Dracula seems like the wrong thing to say, not to mention an overoptimistic interpretation of the situation, so he settles for, taking an evening stroll. What can I do for you? Whitby. The DM pronounces the name of the seaside village in a doom-laden tone that Alex feels demands a more ominous payload, something like, the Third Reich or Mordor. You just happen to be taking an evening stroll in Whitby. Tell me, have you noticed anything out of the ordinary on your perambulations? Across the park, the Brides of Dracula are running for their lives, pursued in circles by a squad of fearless vampire hunters, vanishing stakes that look suspiciously like outof-season cricket stumps. No, why? Did you see anything along the seafront? Behind him, the audience claps appreciatively. One out. I mostly saw the sea. What were you expecting? Mermaids? A pause. Quite possibly. I'm led to believe that Blue Hades with a class-three glamor can pass for a mermaid, yes. But that's not what I was asking about. Well, I didn't see anything. Alex hunches his shoulders instinctively. Well, apart from the usual, out-of-season tourists seafront and a troupe of actors rehearsing an outdoor performance of Dracula for the Goth festival. Did you even read your briefing pack? The DM's voice rises angrily. What briefing pack? Alex is perplexed. What? Please hold. The phone goes silent for perhaps half a minute. Alex makes his way along the side of a path. Watching a Van Helsing rescue a sleepwalking Mina Murray from the clutches of a undead Lucy Westenra. There is no sign of Cassie while he waits for the DM to resume the call. Finally, a tinny, throat-clearing sound emerges from the speaker. Dr. Schwartz, please accept my apologies. I'm monitoring operation in your vicinity and naturally assumed from your presence in the grid that you were part of it. An operation? Alex shakes his head. I was sent to Leeds for next week. I'm working regular office hours, so I'm sightseeing right now. Because it's the weekend? Why are you not in Leeds, the DM demands waspishly, as if Alex's delinquency on his time off is something he finds personally offensive. Have you ever seen Leeds on a Saturday night? It may not be the real reason for his absence, but it's a perfectly serviceable excuse. The nightlife in the city center is more than a little raucous. Well, then. The DM seems to come to some sort of conclusion. Would you like to make yourself useful, Dr. Schwartz? The field team is shorthanded, and I have a little job you might care to undertake. And I'm going to stop at that point. And I should add that that book is due out next July, so one a year for a little bit. And now I think we've got about 10 -- how long have we got left for questions? About 10, 15 minutes? >>: Yes. >> Charles Stross: Yes, okay. I'm going to open the floor for questions. Okay, you, sir. >>: So years ago, Accelerando of course first brought me to your literature, but the short story, A Colder War, completely blew me away when I first read it. I think you have made some comments in the past, which is kind of a Laundry File, but super-serious, but James Bond meets Cthulhu. Did that stick with you that turned into the Laundry? Was it part of an inspiration? How did that kind of evolve? >> Charles Stross: Okay. I began writing A Colder War in 1991, before I had any idea of making it a Lovecraftian story. It was going to be -- it was an attempt of getting across the sensation of what it was like to grow up in the UK during the Cold War, with the sense that vast, remote alien intelligences could decide to burn your face off and kill everybody you know at short notice for incomprehensible ideological reasons of their own. And I'd got a couple of pages done and then hit a brick wall, and couldn't figure out how to make it work. And I had to get that sense of existential dread across. And it stayed on the shelf for about five years, and then I suddenly realized, of course, At the Mountains of Madness. It's a sequel to At the Mountains of Madness. Let's take Lovecraft seriously. What would have happened if the story of At the Mountains of Madness had been part of our history. Well, there would have been an arms race to loot all the elder race's weapons from the city in Antarctica. And, of course, it would have then ended up with [shog off] gaps and Cthulhu being weaponized and everything that went into that story. So I wrote that story, and it worked pretty much as a standalone, but oh, dear God, it's a bit of a downbeat one. I could not do that at novel length, and a couple of years later, I had this idea, I wanted to do a Slashdot-reading, sandal-wearing geek. This was sort of 1998-ish, dot-com 1 era, who's fallen into a British -- your classic seedy British spy thriller secret government agency. And I suddenly realized, hello, let's bring some tentacles into this, because A Colder War isn't funny at all. The Laundry Files is dark humor the whole way and seems to work better for it, but yet it was not a dry run exactly, but it was where I first began getting into the Lovecraftian thing, into actually writing it. You, sir. >>: Yes, a question about Bob, the character. >> Charles Stross: Could you speak up, please? >>: Sure. Sorry, of course. Is Bob at this point just a VM running on a part of a hypervisor? >> Charles Stross: I'll have to get back to you on that. Do we have some more questions? >>: Is there some reason why you like writing in the present tense? >> Charles Stross: Okay, the present tense versus the past tense, there's this whole grab bag of tools you can use. Which tense you write in, which person you write in, whether first person or third person, or occasionally, second person. Let me give you a tip. Never, ever, ever, ever try writing fiction in the second-person future pluperfect. Your brain will melt. No, the reason it's present tense is narrative tension. The reader never really knows what's going to happen next. Flipside, first person is a bit of a giveaway that the narrator is going to survive to the end of the book, except in Glasshouse, when I killed off the narrator two-thirds of the way through the novel. Seanan McGuire has pulled that stunt, as well, so it's usually a sign that you've got an unreliable narrator. But it's just the immediacy and the immediate punch and impact, and I started that way in the Laundry Files, and I'm carrying on with it. Other books I've written are more conventionally structured in the past tense. I don't think I've got the guts to try and write an entire novel in the future tense. >>: I read the first Laundry Files book myself, and then shared the series with my wife by getting the audiobooks, all read by Gideon Emery, and I was wondering if you had any selection, any involvement at all in the process of turning it into an audiobook. >> Charles Stross: None. I don't do audiobooks, and the rights are sold to Recorded Book, who then organize everything themselves. >>: Oh, really? >> Charles Stross: Yes. I could in principle get involved if I felt strongly enough about it to want to get involved, but I'd be negotiating with people through my agent, and it gets complex and annoying fast, doing that. More questions? >>: We had some online questions. Actually, another question about the audiobooks. It sounds like maybe you don't have an answer, but wondering if this last because, because it's Mo as the narrator, if you'd have that a female, but it sounds like you're not necessarily involved. >> Charles Stross: No. >>: Okay. And the other question was maybe a slightly pointed, but it says, Bob Howard seems to have a problem with all things Microsoft. Personal experiences at Microsoft? >> Charles Stross: I will confess to having worked for a rival operating system vendor at one point. More to the point, I'm just a Unix guy. My head doesn't work -- I periodically make an attempt to grapple with Windows, and it just doesn't really work for me. When I'm at home, I'm currently swearing at a Surface 3, trying to make it do what I want to do. I'm sure -- it's a really nice piece of hardware design, and I'm sure it'll work really well if you're committed to the Microsoft application ecosystem, but virtually nothing I use day to day for work is a Microsoft application. I think you were next. >>: Are we going to see Angleton again? >> Charles Stross: No comment. That would be a spoiler. You, sir? >>: So in the past, I think you've stated that you can't write a sequel to Rule 34, because there's just not that much more to expound upon at this point. >> Charles Stross: Nope, it's not about not much more to expand upon. What happened is I began designing that universe in 2005, and it was set in 2017. It's diverged too much. Also, around the time I would have begun writing the Lambda Functionary, the third book in the trilogy, we ran smack-bang into what I call the Scottish Political Singularity, which we're not out of yet. You cannot write near-future fiction set in Scotland at present without it being horribly obsolete within 18 months. It's just not doable. So I'm probably going to do more in a similar line later, but it won't be in that setting. You had a hand up earlier? >>: Will we learn more about the black chamber? >> Charles Stross: Yes, in book nine. Yes, you're going to have to wait. There is a long-term story arc planned out. I'm going to give priority to people who haven't already asked questions. You first, I think. >>: I've heard rumors of maybe a new three-book set on the family trade. >> Charles Stross: Yes. It won't be sold as Merchant Princes books. It'll be titled the Empire Games Trilogy. Book one, Dark State, comes out next September. It's my big, fat post-Edward Snowden grim future techno-thriller, with alternate universes. But yes. Original working title, though, was Merchant Princes, the Next Generation. It's set in 2020, in a timeline where the Department for Homeland Security has responsibility for securing the United States against threats from all other parallel universes. And then it goes downhill from there. Someone back there have a hand up? You, sir. >>: Yes, so I was wondering for -- so I read Glasshouse as the original book I read of yours, and then have expanded into the Laundry Files and whatnot. I was wondering, is there going to be -do you have any plans for any books that have A gates and T gates and all sorts of other fun, Glasshouse-y things? >> Charles Stross: I did actually try to sell a sequel to Glasshouse a few years ago. Unfortunately, Glasshouse is my slowest-selling SF novel in the US market, and got to eat. I might have enough clout to do it one of these years, but it wouldn't actually be sold as a sequel. It'd be sold as a standalone novel, and it's something I wrote in 2003, so coming back to it, it's difficult to maintain interest in a lot of projects that you did 10 years ago or more. I'd have to actually really feel the need to say something in that setting to go back to it. >>: So has the growth and popularity of ebooks and audiobooks affected your actual writing at all, like the construction of your writing? >> Charles Stross: It hasn't affected the construction, particularly, because it's just another output format. Or rather, it hasn't affected it much yet. One of the factors that people really don't appreciate outside the business is things like the length of books being dictated via the sales channels and the manufacturing practices. For example, it used to be the case that I could not write a novel that ran to more than 416 pages, or my editor would scream at me and make me take some of them out. The reason being, hardcover books in the US are still made the traditional way, by printing 16 up, folding into signatures, and then stitching them. And only a limited number of book binderies can stitch big, fat novels in hardcover. So the length of my novels was determined by the mechanical strength of a sewing machine. That constraint has now been lifted, but you can see how this is going to change with ebooks. The length constraints that used to be imposed by printing technology just aren't there anymore, so over time, we're going to see major changes in the way things are produced. I'm not sure, for example, there's any point in me ever bolting together another short story collection, because individual short stories can be published online and sold direct. Nothing needs to go out of print. And I think time for a last question? >>: So the Case Nightmare Green, as the density of thinking becomes larger, it becomes easier and easier for evil things beyond space to come in, doesn't this mean datacenters for cloud computing providers are going to become like the ground zero for horrible things? And if so, why isn't the Laundry all over Microsoft and Amazon? >> Charles Stross: How do you know they're not? Anyway, I think -- is it time to wrap yet? >>: Thank you so much. >> Charles Stross: Right.