Long-Run Biases in Consumer Sentiment Micro Evidence from European Surveys Maurizio Bovi

advertisement

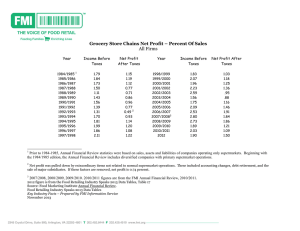

OECD Workshop on Business and Consumer Tendency Surveys Rome, 19 September 2006 Long-Run Biases in Consumer Sentiment Micro Evidence from European Surveys Maurizio Bovi ISAE, Italy Plan Fit Goal and Contribution Motivations Data Statistical Framework Experiments and Results Puzzles or well known Psycho-Biases? Concluding Remarks Fit Data users often take consumer sentiment indexes (CSI) as a given input and, by and large, they search for links between CSI and Economic System “hard” data. Data producers think about CSI as a final output, addressing issues such as data collection, response rates, etc. Roughly speaking, they deal with mapping Individuals into CSI. My research examines “semi-worked” survey data without reference to hard data and focuses on their reliability and on how Individuals address the Economic System. Goal and Contribution A long-run analysis of the consumer sentiment, taking advantage of micro data (% of respondents) and cognitive psychology findings. Keywords: long-run analysis; representative consumer; micro data. Motivations Why micro data? In many political and economic circles, CSI are commonly diffused, commented and studied at their “face value”. Looking at CSI components may be interesting even from the data users point of view. Analyzing micro data allows avoiding comparisons with National Account data which, in turn, reduces problems such as the vagueness/difficulty of the queries. E.g., how does the respondent interpret queries about “general economic conditions”? Motivations (2) Why a long-run analysis? Inter alia, this Workshop is about consumer tendency. I have enough data (assuming that twenty years are enough for a long-run analysis). To some extent, a long-run approach may sidestep some data issues (changes in survey methods, seasonality, etc.) Data Data are from the Business Surveys Unit of the European Commission. I deal with the following queries and with the relative reply options: Q1) How has the financial situation of your household changed over the last 12 months? It has ... Q2) How do you expect the financial position of your household to change over the next 12 months? It will ... Q3) How do you think the general economic situation in the country has changed over the past 12 months? It has ... Q4) How do you expect the general economic situation in the country to develop over the next 12 months? It will ... PP) P) E) M) MM) N) get/got a lot better get/got a little better stay/stayed the same get/got a little worse get/got a lot worse don't know. Data (2) • are percentages of respondents: MM+M+E+P+PP+N=100 • refer to fifteen European Union (EU) countries • start in January 1985 for nine out of fifteen countries Exemptions are: Austria (starting date 1995:10), Finland (starting date 1987:11), Luxembourg (starting date 2002:01), Portugal (starting date 1986:06), Spain (starting date 1986:06), Sweden (starting date 1995:10). • stop in July 2005 for all countries. Statistical Framework I analyze: i) stylized facts via ii) full-sample descriptive statistics about iii) representative consumers within iv) the survey framework All that should reduce some data issues (the lack of re- interviews, changes in survey methods, seasonality, vagueness of the queries), allowing robust findings. Experiments and Results Some simple experiments based on reply options allow verifying the persistent presence of “logical” behaviors. They may be thought of as somewhat supporting the reliability of the answers. For instance: Consumers should know their own situation better than the system wide one. Thus, e.g., the average share of individuals answering “don’t know” to questions about the general economic environment should be greater than the average share of individuals which do not know how their own financial situation is going on. Consumers should know past situations better than future ones. Thus, ex ante questions should show more “don’t know” than the corresponding ex post ones. Consumers’ Uncertainty on Personal vs General and on Past vs Future Economic Conditions Personal General Table 1 (Q1) Past (Q2) Future (Q3) Past (Q4) Future AUSTRIA 0.98 2.97 2.43 4.04 BELGIUM 2.96 6.69 6.05 10.8 GERMANY 1.36 4.73 2.32 5.58 DENMARK 0.66 3.7 7.11 8.85 GREECE 0.16 4.46 1.95 7.68 SPAIN 1.09 9.68 5.37 14.8 FINLAND 0.6 3.59 3.34 4.89 FRANCE 0.48 4.23 1.66 8.76 IRELAND 0.94 4.88 1.97 6.97 ITALY 0.5 4.68 1.95 6.32 LUXEMB. 1.16 3.46 4.67 5.59 NETHER. 1.08 4.5 7 11 SWEDEN 0.77 2.21 5.49 4.77 PORTUG. 1.33 11.2 5.47 15.7 UK 1.57 5.93 4.62 9.84 EU_11 1.02 5.08 3.93 8.58 EU_11=Belgium, Germany, Denmark, Greece, Spain, Finland, France, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, UK (sample 87:11-05:07). Full sample average of responses “don’t’ know” (in % of total) to the questions Q1-Q4. Experiments and Results (2) Let us now turn the attention to the “E” answer. There are reasons to believe that it should show the largest scores: 1. Since the queries are about “dynamics”, individuals should respond, on average, “the same” the most part of times, because it is hard to think of ever improving/worsening economic conditions over many years. It is important to note that it should hold whatever “economic conditions” means for common people. 2. The preference of being “E” may be partly due to short-cut heuristics - this “neutral” option may be chosen by uninformed and/or uninterested respondents. Fig. 1. Distribution of Responses On Economic Conditions EU11 70 E E 60 50 E 40 30 20 M P P MM 10 PP P M E M P MM MM N PP N PP M N PP MM N 0 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Histograms report full sample (87:11-05:07) means of each reply item. EU11=Belgium, Germany, Denmark, Greece, Spain, Finland, France, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, UK. Experiments and Results (3) Given their “logically expected” outcomes, all the tests performed so far on N and E lead to think that data give a faithful representation of people’s opinions. In passing, neither N nor E enter into CSI. Data tell more than this. Figure 1 shows that the number of E-agents is structurally much higher when the question is about personal (Q1, Q2) as opposed to general (Q3, Q4) economic developments (more than 55% vs less than 40%). This calls for ad hoc tests to contrast general vs personal response options. One way to proceed is computing mean values of [(Q1+Q2)-(Q3+Q4)] for each single option. When referring to “MM” and “M” (“PP” and “P”) percentages, negative (positive) values imply that the personal condition is perceived to be systematically better than the general one. Personal vs General Sentiment in European Countries Table 2 PP P M MM AUSTRIA 1 -19 -25 -8.1 BELGIUM 1 -8.9 -26 -19 GERMANY 0.6 -5.6 -23 -12 DENMARK 10 -1 -17 -3.4 GREECE -0.7 -6.2 -5.3 -5.5 SPAIN -0.3 -9.6 -16 -9.3 FINLAND 3.8 -19 -14 -3.9 FRANCE 2.2 1.5 -31 -23 IRELAND -3.8 -16 -10 -13 ITALY -1.8 -15 -22 -26 LUXEMB. 2.8 1.7 -50 -8 NETHERL. 5.1 -12 -15 -9.9 SWEDEN -0.4 -4.6 -22 -8 PORTUGAL 6.6 -11 -21 -2.9 UK 5.3 -2.7 -14 -14 EU_11 2.1 -8.1 -18.6 -12.7 EU_11=Belgium, Germany, Denmark, Greece, Spain, Finland, France, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, UK (sample 87:11-05:07). Black values indicate that the personal condition is perceived to be better than the general one. Experiments and Results (4) According to one of the basic axiom of standard neoclassical models, agents should not persist in repeating the same mistake. In the present framework, it may be addressed by looking at the gap between “contemporaneous” ex ante (Q2, Q4) and ex post (Q1, Q3) responses, to which I refer as the “forecast error” (i=PP, P, E, M, MM): forecast error = 100*[Q1i-Q2i-12)]/[Q1i+Q2i-12] Likewise for general conditions (Q3-Q4). For MM and M, positive errors indicate over-optimistic expectations and/or over-pessimistic judgments. E.g., today 30% judges the last a “worse” year, 12 months ago 10% foresaw it as a “worse” year. The reverse holds for PP and P. It is noteworthy that, in this setting, there is no need for agents to correctly address what an “economic situation” really is. In fact, I just compare answers given to the same question. Europeans’ Forecast Errors (MM) AUSTRIA_PERSONAL AUSTRIA_GENERAL BELGIUM_PERSONAL BELGIUM_GENERAL 100 100 100 100 50 50 50 50 0 0 0 0 -50 -50 -50 -50 -100 -100 1986 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 -100 1986 1988 1990 GERMANY_PERSONAL 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 -100 1986 1988 GERMANY_GENERAL 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 1986 100 100 50 50 50 50 0 0 0 0 -50 -50 -50 -50 -100 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 -100 1986 1988 1990 GREECE_PERSONAL 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 1988 1990 GREECE_GENERAL 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 1986 100 50 50 50 50 0 0 0 0 -50 -50 -50 -50 -100 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 -100 1986 1988 1990 FINLAND_PERSONAL 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 1988 1990 FINLAND_GENERAL 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 1986 100 50 50 50 50 0 0 0 0 -50 -50 -50 -50 -100 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 -100 1986 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 2000 2002 2004 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 2002 2004 FRANCE_GENERAL 100 1988 1990 FRANCE_PERSONAL 100 1986 1998 -100 1986 100 -100 1996 SPAIN_GENERAL 100 1988 1988 SPAIN_PERSONAL 100 1986 1994 -100 1986 100 -100 1992 DENMARK_GENERAL 100 1986 1990 DENMARK_PERSONAL 100 -100 1988 -100 1986 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 1986 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 Europeans’ Forecast Errors (MM) IRELAND_PERSONAL IRELAND_GENERAL ITALY_PERSONAL ITALY_GENERAL 100 100 100 100 50 50 50 50 0 0 0 0 -50 -50 -50 -50 -100 -100 1986 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 -100 1986 1988 LUXEMBOURG_PERSONAL 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 -100 1986 1988 LUXEMBOURG_GENERAL 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 1986 1988 NETHERLANDS_PERSONAL 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 2002 2004 2002 2004 NETHERLANDS_GENERAL 100 100 100 100 50 50 50 50 0 0 0 0 -50 -50 -50 -50 -100 -100 1986 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 -100 1986 1988 PORTUGAL_PERSONAL 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 -100 1986 1988 1990 PORTUGAL_GENERAL 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 1986 100 100 50 50 50 50 0 0 0 0 -50 -50 -50 -50 -100 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 -100 1986 1988 1990 UK_PERSONAL 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 2000 2002 2004 UK_GENERAL 100 100 50 50 0 0 -50 -50 -100 -100 1986 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 1986 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 SWEDEN_GENERAL 100 1986 1990 SWEDEN_PERSONAL 100 -100 1988 -100 1986 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 1986 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 Europeans’ Forecast Errors Statistics (mean; % in 5% band) (PP) -3.1 -15.1 4.5 -10.1 17.0 22.1 6.1 4.2 -12.3 -25.2 6.2 17.4 6.4 11.9 -9.8 -19.3 14.2 4.0 25.1 16.6 14.0 6.8 17.9 21.3 7.7 6.4 15.1 12.8 17.9 4.5 20.0 8.9 23.6 28.3 -1.7 -32.2 2.9 -27.5 16.8 4.0 2.1 9.2 12.8 -1.4 9.0 -7.3 11.1 5.5 13.6 7.7 19.4 9.7 8.5 6.4 18.3 17.9 17.9 5.7 23.4 14.9 (P) -28.4 -17.9 -10 -16.4 3.8 -10.4 -4.6 -4.4 -24.7 -24.6 -17.3 -10.9 -9.7 -16.7 -23 -39.9 0.9 12.3 23.8 8.9 26.8 10.6 44.7 17.0 10.6 8.1 11.0 28.0 44.3 20.9 2.1 6.8 -5.5 -5.3 -25.5 -35.6 -16.5 -34.0 -3.2 -13.7 -16.9 -18.2 -8.1 -10.7 -10.8 -15.5 35.7 17.4 14.0 6.8 9.7 0.0 37.0 12.8 9.6 9.2 41.5 14.2 24.3 16.2 (E) 1.7 -15.7 -2.1 -8.5 -7.2 -12.0 -2.3 2.8 -5.4 -8.4 3.3 -4.4 -0.9 -4.0 0.6 -5.5 50.9 13.2 67.2 26.0 34.5 23.0 75.3 50.6 34.9 31.5 66.5 47.7 90.0 26.4 89.8 40.4 -8.3 -18.6 -4.5 -15.1 4.5 -13.4 -3.5 -4.0 7.2 -1.7 0.4 -1.7 -3.9 -8.6 26.4 12.3 64.7 23.0 58.1 25.8 64.3 24.3 36.2 23.9 80.2 46.2 47.7 29.8 Europeans’ Forecast Errors Statistics (mean; % in 5% band) (M) 4.6 16.6 21.5 12.7 20.2 7.1 15.9 -5.3 21.8 25.3 22.9 18.7 16.7 0.6 16.4 12.6 25.5 26.4 12.8 21.7 11.1 15.7 15.7 13.6 8.9 3.8 6.9 11.0 10.4 9.0 12.3 15.7 21.7 4.6 32.8 20.3 7.6 26.1 4.4 -6.3 12.1 14.1 7.1 6.2 13.8 12.7 5.1 29.8 1.7 13.6 25.8 3.2 21.7 16.6 25.2 18.3 29.2 17.0 16.2 17.4 (MM) 34.1 31.8 36.9 25.4 35.6 29.3 39.5 -0.7 13.3 9.6 35.6 27.1 42.3 21.3 33.5 31.2 3.8 7.5 8.1 9.8 1.3 5.1 4.3 18.7 11.5 11.5 1.8 5.0 3.0 10.4 1.7 7.2 36.5 25.6 46.7 38.2 33.0 24.4 29.5 13.7 21.8 18.4 40.5 22.0 32.8 24.4 3.8 5.5 0.9 5.1 3.2 6.5 3.0 14.0 8.3 6.0 1.9 6.6 1.3 8.5 Puzzling Results People’s tendency to judge over-pessimistically and/or to forecast over-optimistically. The ambiguity arises because of the lack of a “hard” benchmark (e.g., GDP, Consumption, etc.). However, it implies that: people’s forecasts show a long run bias. people’s tendency to think that their own economic situation is better than the general one - the representative consumer think to become “richer” than himself. To sum up, there seems to be a structural mantra echoing across Europe: As Usual, it Has Got Worse Than I Expected. Especially for the Others. Nevertheless, I Still Think That it Will Get Better. Especially for Me. Puzzles or well known Psycho-Biases? Over-pessimism in judgments Availability bias. Mere repetition of certain information in the media, regardless of its accuracy, makes it more easily available and therefore falsely perceived as more accurate. Since the media tend to overweight bad economic news (Doms and Morin, 2004), there are reasons inducing individuals toward dispositional pessimism. Moreover, the information flow may also run from people to media (Curtin, 2003), creating a perverse spiral. Over-optimism in forecasts Irrational exuberance. In uncertain situations people tend to make forecasts by assuming, often without sufficient reasoning, that future favorable patterns will resemble past ones. Law of small numbers. People tend to over-inference from too short sequences of observations. Hindsight/Confirmation bias. Individuals tend to concoct ex post “logical” explanations for ex ante totally unexpected events. All that prevents agents from adequately learning from the past and from being aware of their errors, leading to long-run biases. Puzzles or well known Psycho-Biases? (2) Over-pessimism in judgments and over-optimism in forecasts Mental Accounting. People “allocate” current and future income in different “accounts”. Over-self-confidence Illusion of Control. People have an expectancy of a personal success probability inappropriately higher than the objective probability would warrant. Depressive realism. One interpretation of it is that nondepressed people possess a positive bias, which allows them to feel in control of their environment. Since, hopefully, the representative European is non-depressed, evidence supports the agents’ egocentric bias. Concluding remarks When elicited about economic conditions, people tend to reply both as expected and irrationally. Empirical evidence highlights paradoxical (rectius, emotionally-driven) responses, even when dealing with familiar conditions. Thus, it is not only a problem of the amount/quality of available information and/or the difficulty of the exercise - there is something else preventing “Muthian” results. My research suggests that psychology may be of some help. To the extent it is true: not necessarily the detected puzzling outcomes reduce the reliability of survey data, it may be useful adding psychological considerations to CSI – biases are structural => manageable After all, everybody should agree that the sentiment is a mix of rationality and feelings…