Chris Connolly Research questions: up empowerment programs?

advertisement

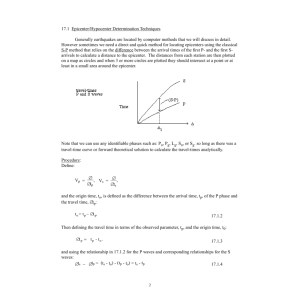

Chris Connolly Research questions: 1) What is the local role of The Hunger Project’s project facilitators in scaling up empowerment programs? 2) What are the organizational and programmatic features of The Hunger Project that promote (or constrain) the fulfillment of this local role on a wide scale? Making Equal Rights Real/ Vers la pleine réalisation de l'égalité des droits May 1, 2010 McGill University THP Overview INGO that employs a bottom-up development strategy in 13 countries in the global South. Conceptualizes the empowerment of individuals and communities as the means to overcoming hunger and poverty. Pursues goals around the MDG framework through their epicenter strategy. Organizational structure Operates in a decentralized manner through their Global Office in New York. THP-Global provides financial management and strategic oversight. Program scale-up Attempting to “change the way the world does development” by demonstrating the scalability of The epicenter strategy Mobilizes clusters of rural villages to the epicenter strategy. implement THP-initiated programs and projects. Epicenter approach was consolidated into a wellFocuses on the right to meet basic needs defined, five-year phased process to be implemented through community self-reliance. for the first time in the Eastern Region of Ghana. Dozens of multi-sectoral projects take place Field work took place at the beginning of the third within the community-built epicenter building. year of scale-up in July-August, 2009. “Our mission is to transform the way the world does development. We’re never just doing our projects for their own sake. We actually want to convince the world that this is the way to go. […] By 2004 and 2005, we noticed that… our package, our methodology was probably as good as it was going to get.The moral imperative at that point is to scale up.” —VP Strategy & Impact, THP-Global Community-based development (CBD) Involves promoting community involvement within international development programs. Defined by the WB as “strengthening community groups with training support, providing them with an opportunity to control decisions and resources… and creating an enabling environment for these activities.” Empowerment and participation A complex theoretical construct that roughly corresponds to increasing the degree of choice over development decisions. Contains two subcomponents: agency (i.e. assets) and opportunity structure (i.e. institutions). The role of external project facilitators Field workers have a crucial role in negotiating project objectives with local populations. Very little generalizable evidence on their role. Case study evidence: facilitators can successfully realize community participation and project success, but this local role is fraught with difficulties. Scaling up CBD Scale up: refers not merely to a technical or mechanical exercise, but to principles and processes. Implies adaptation, modification and improvement and not just replication. Requires a corollary process of ‘scaling down’, by which managing partners must adapt modes of operation that are supportive of communities. Scaling up the role of facilitators in CBD If success in CBD can be negotiated locally by external facilitators… How and to what extent can this dynamic be recreated by large donors and INGOs? Case site selection A multiple-site design was employed with the selection of two epicenter case sites at early and late stages of implementation: Site 1 – Early-stage epicenter. Site 2 – Intermediate-stage epicenter. Quantitative and ethnographic methods Interviews: ~50 semi-structured, open-ended interviews. Subjects included academics, local politicians, THP facilitators, national and international THP leaders, community volunteers. Observations: Observed 8 THP workshops and committee meetings. Accompanied by translator. Eastern Region Site 1: Dominase epicenter Site 2: Supreso epicenter Sensitizing community members and promoting the role of women Developing leadership Constructing the epicenter building Creating the epicenter community Coaching communities through THP project implementation Facilitating new community projects Building agency (improving assets) Reshaping opportunity structures (opening up institutions) • Sensitizing community members • Developing leadership • Promoting the role of women • Creating the epicenter community • Coaching communities through THP project implementation • Facilitating new community projects Epicenter building construction Selfsustaining basic needs interventions “I can see that, when THP is no longer coming here, the community people will realize that [the epicenter building] belongs to them… When they leave us, and we are on our own… we will discuss it and decide among ourselves.” —Epicenter Chairman, Supreso epicenter District level (Intermediary) Opportunity structure Domain Subdomain Agency *Formal and Public informal service State networking with delivery local gov’t Labour Goods Market Private services Society Intracommunity Level Epicenter level (Local) Opportunity Agency structure *Gov’t provision of resources and expertise (e.g. nurses for clinic) *Agricultural training *Microcredit program *Community farm *Communityinitiated projects *Epicenter *Leadership committees training *Sub-committees *Skills training *Association of *Conscientization chiefs workshops *Gender quotas Village level (Sub-local) Opportunity Agency structure *Gov’t provision of resources and expertise (e.g. building materials) *Corresponding Village-level improvements *Corresponding Village-level improvements *THP village committees *Changing gender roles Table 3: Overview of the ‘theory of change’ of THP’s epicenter strategy. Visual illustration of the theory of change behind THP’s epicenter strategy in terms of how particular primary and secondary actions fit within the empowerment analytic framework. Source: Adapted from Alsop et al, “Empowerment in Practice: From Analysis to Implementation” (2006), Box 5.2, p. 63. Obstacles to effective empowerment at the local level are expressed as a lack of commitment to community participation. Reasons for lack of local participation Explicit rejection of the principle that communities should work for themselves. Unwillingness of elites to cede authority. Disempowered state of mind (e.g. fatalism). Inability to participate due to, e.g., distance or the outcomes of poverty. Communities sufficiently protected by other communal resources (e.g. a clinic). Community characteristics Local power structures undermine inclusive form of participation. Old prejudices about the way village society ought to be organized (e.g. gender dynamics). Low levels of education. Lack of community resources and capacity. Community expectations Culture of dependency on external actors. Perceived “Otherness” of THP and facilitators. Structural nature of problems Village level implications of structural problems (e.g. poverty and social marginalization) “When [THP] said that there is no money and... therefore, we are going to do it ourselves, then... a lot of people got out from there. Some people, it is their ideology that the government provides all the necessary funds to do everything.” —Epicenter committee member, Dominase epicenter “It’s a big distance to be able to get the committee members to understand this whole framework… It’s complex. Empowerment depends on where you are taking the people from—it can be a long and winding journey.” —THP-Ghana National Programs Officer Enormity of goals Personnel requirements Tremendously ambitious range of programs. Decentralization results in large, dispersed and Fundamental reorganization of village society. heterogeneous staff. All this in a five-year window of involvement. Organizational complexity of interventions Strategic imperatives and donor and programs Complexity: extensive network of committees; expectations Formalization of implementation plan into 5- overlapping volunteer roles; myriad basic needs year process with fixed yearly targets. projects; amorphous role of THP staff. Unintended outcome: Delay or de-emphasis Implications for community: confusion over roles/ of empowerment activities (e.g. training, responsibilities; failure to gain high-level mobilization) vs. building construction. understanding of project. “We need a kind of a compromise between having things done within reasonable time, and at the same time allowing the communities some time to mobilize. We shouldn’t forget the reason why we are in the villages—it’s because they are poor. You have to stop and ask yourself: Are you overburdening them with your approach?” —THP-Ghana National Programs Officer “There’s always this kind of tension between the pure field practitioner who wants to stay with each family forever and have them maximally empowered, and the bigger picture called—Look, children aren’t going to start being saved and food security won’t be assured until the building is there. So let’s move it along. It’s a healthy tension.” —VP Strategy and Impact, THP-Global Overview of main findings THP employed a process of phased scaling up to expand their intended agency-building and structurally-transforming empowerment program. Community informants, while demonstrating an increased ‘capability to aspire’, engaged minimally with proposed structural transformations compared to the operational imperatives of concurrent basic needs interventions. Observations of project implementation divulged well-qualified, autonomous personnel struggling to prioritize community empowerment amidst overall organizational priorities from above. Interviews with international THP leadership revealed an organizational philosophy of ambitious goal-setting, results-oriented action and self-reflective learning by doing. Decentralization of decision-making and autonomy/ training of field staff Actions: autonomy of field staff to innovate and adapt to local circumstances; training to do so in an effective manner; group-based learning and collaboration. Allows facilitators to perform their myriad facilitative, educational, representational and technical roles. Recognition of the need to empower facilitators themselves. A learning-by-doing approach to local empowerment Actions: building community/ individual agency by coaching people through project implementation; encouraging the initiation of new village projects. Legitimates the diverse ways in which people participate. Values local culture, knowledge and skills. Community-building and institutionbuilding Actions: creates formal committees and volunteer roles; fosters sense of community and solidarity. Formal institutions do not present very viable community processes. Excessive organizational complexity may frustrate progress. The pace of development Actions: five years to complete the program; construction of the building within the first year. Facilitators do not have enough flexibility to adjust the pace to suit community needs. Centrality of building seems overstated, receiving disproportionate attention vs. empowerment activities. The long-term nature of community development is not given proper emphasis. Adapting the model to local circumstances Actions: in-country innovations to particular socio-political realities; staff structure that allows facilitators to make further tweaks Incorporates local needs and processes to some extent, but not enough! The development process is not truly developed within and by the community. Addressing structural disadvantage Actions: working primarily at the local level to combat the effects of hunger and poverty. Does not sufficiently take account of class, although gender is given proper attention. Motivation and confidence are important, but it is insufficient to claim that people can get what they want if only they work hard at it. Consciousness-raising should be given more thorough attention. Sheer number of programs may be too much of a burden on people who are, after all, poor. Evidence supports the idea that scaling up empowerment programs requires an organization-wide commitment to (a) well-trained, autonomous and locally-sensitive field staff; (b) a culture of continuous learning and flexibility; and (c) a gradual approach with long time horizons. Project facilitators must have the time and flexibility to adapt specific empowerment strategies to the particular historical, political and social environments of program sites. Program coordinators must take into account the degree of empowerment of the facilitators themselves, including their agency and opportunity structure. These conclusions support a consensus on the need for prudence in the wide-scale implementation of community-based programs. Special thanks to: Magda Barrera, Tinka Markham Piper, Norma Vite Leon, Leo Perez Saba and all IHSP staff… for your guidance and support. The staff of THP-Global… for providing the opportunity to make this study a reality. The staff members and Project Officers of THP-Ghana… for your commitment to reinvigorating village life in Ghana. My translator and host family in Ghana… for your devotion, hospitality and camaraderie. The people of the Dominase and Supreso epicenters… for being my inspiration throughout the last 9 months.