HOW REVOLUTIONS IN RELIGION, TECHNOLGY,

advertisement

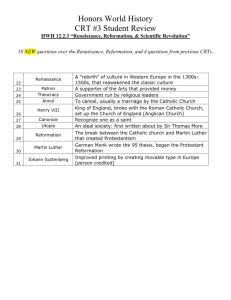

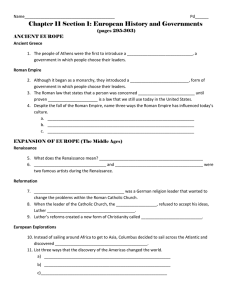

HOW REVOLUTIONS IN RELIGION, TECHNOLGY, IDEOLOGY, AND POLITICS EMERGE SIMULTANEOUSLY Jill Stiemsma July 31, 2001 AS INSTITUTIONS CHANGE…. Consider that one of the Performance Standards for this unit reads: “Learner determines how changes in one institution impact other institutions.” This is indeed a fundamental principle of Social Change. Many people, for example, suggest that we must return to “traditional family values.” What they fail to appreciate is that changes in one institution – be that technology and science or politics – necessitate changes in other institutions. Herein, let’s examine the relationship among institutional changes as we marched toward the industrial era. Never did we see such important social change occurring simultaneously within institutions as the era preceding the industrial revolution (when humankind moved from late agricultural – beginning about 400-500AD – to industrial, 1750+). Writes author Jack Weatherford in Indian Givers: Despite all this coming and going, the way of the life of the villagers changed very little for thousands of years. Once the Neolithic hunters settled down to farm crops, life took on a fairly consistent form. The daily routine for the villagers during the Roman times differed little from the life under the Holy Roman emperors or the archbishop of Mainz. The peasants grew their crops, paid their taxes to the lords clerical and secular, and sent their sons to fight in the wars of both lords. The names of the rulers changed from century to century, but little else did. Great intellectual movements passed them by, and even the great religious changes of the world had minimal impact on their lives. … Farm life in Kahl, Germany, remained much the same regardless of whether the village was inhabited by the Celts, the Chatten, the Romans, or the Franks. … What happened in the 1700s and 1800s after thousands of static years of technological stability? If you think about it, this transformation is an amazing story, especially in light of all the changes that occurred in just the last 500 years! So, let’s examine the changes occurring to the heart and soul of religious, technological, ideological, and thus political life preceding the industrial era. The Religious Reformation Why did we call it the “Holy Roman Empire” rather than simply the “Roman Empire”? The answer, plainly, lay in the “divine rights of kings.” That is, Middle Ages Christian theologians determined that the king ruled in God’s place; thus was it the duty of the king’s subjects to be loyal to him (and to pay their taxes!). “To disobey the king was to disobey God! In some areas of the world, kingdoms went a step further by decreeing that the leader was God. The religion of ancient Egypt held that the Pharaoh was a god. The Emperor of Japan was similarly declared divine. If this were so, who could even dare to question his decisions?” (Henslin, Fifth Edition, 370) In the Holy Roman Empire, then, the reigning monarch and the pope constantly vied for power: Was the king the head of the church or did the church hold power over the king? Therefore, who could choose the bishops: the king or the church? By Catholic doctrine, papal power was invested by God himself since the pope’s authority directly descended from the Apostle Peter. By no means, then, was this church-state relationship an easy one. Popes and rulers, alike, were routine victims of assassination. But the bottom line was this: The church and the lords owned the vast stores of loot, consistently impoverishing the masses. So imagine when Monks dared to suggest that the Catholic Church had lost its way! Yet in the first 400 years of the second millennia, “Christians” had waged four bloody Crusades – killing, raping, burning, and plundering as they went. When some began to question the ethics of such Crusades, the church responded with the Inquisition. Charged with heresy for speaking against either the church or state, tens of thousands were burned at the stake, beheaded, or otherwise tortured. In the face of this tragedy, monks -- among them Martin Luther -- could no longer remain silent. Now, why did Martin Luther avoid torture and death for preaching “heresy” when others before him did not? In two words: INSTITUTIONAL CHANGE …brought about by… TECHNOLOGICAL REFORMATION Oh, boy. In the mid-1400s, Gutenberg invented the printing press! “So?” you query. Well, for the first time, ordinary people could read the Bible for themselves (heretofore, the Bible was available exclusively in Latin and Greek, learned only by the elite). And if one could read the Bible, one could interpret the Bible for oneself. Heresy, heresy, heresy!!! For this, Tyndale, who translated the first Bible (the King James Version) into English, was burned at the stake. Imagine: No longer must illiterate peasants and priests rely on the church hierarchy for Biblical teachings! Aside: Here again, we see how one institutional change forces other institutional changes. With the Bible written in a language they understood, peasants would learn to read so they could read the Bible…and, hence came the first push toward a mass educational system. But I digress. On October 31, 1517, outraged by the excesses of the Catholic Church, Martin Luther posted his “95 theses,” protests against the practices of the church (hence the term “protestants,” a radical new sect of Christians). Think about what a threat this was to the powers-to-be: In that era, how did they hold together diverse groups of people? Through religion. So a threat to the established religion was a threat to the society as a whole. But, according to Luther, the Catholic Church overstepped moral practice by selling “indulgences” to the wealthy to fund the building of St. Peter’s in Rome; that is, the elite could pay great sums of money to be granted redemption from sin (“Oh, I fornicated with my neighbor’s wife; let me give the priest 100 pieces of gold”). The masses who could afford no such payment were thereby doomed. Consequently, argued Luther, the Church had lost its way, allowing money to replace true penitence. Though Luther was ex-communicated and declared an outlaw, the Reformation had irrevocably begun as his and thousands of his followers’ efforts began the process of building a modern society based on the powerful ideology of the individual: “If I believe, I am saved.” So powerful is this idea of the individual vs. the church/state that almost overnight hundreds of thousands of Europeans broke with the Catholic Church. This could only have happened with the power of the printing press, greater literacy, and a consequent revolution in ideology. IDEOLOGICAL TRANSFORMATION If as Martin Luther preached, all could gain entrance to heaven through faith, think of the ideological shift! Carried a step further by John Calvin, initially in Geneva, Switzerland, it is not by faith alone that one is saved. Rather, only some are saved, but no one knows for sure who is who. Only God knows that. Rather than becoming fatalistic, however, his followers “worked” for God as instruments and vehicles for His word. Immoral people would not be saved by faith alone, they believed. Building a new society in Geneva that was both civil and religious, people had an incentive to work hard…and thus the birth of a new middle class! No longer were peasants doomed to misery and poverty. Read Henslin, Sixth Edition, pages 360-1, for a more complete description on this ideological transformation now coined “the Protestant work ethic.” (Note: A Protestant is a Christian, non-Catholic, today including Methodists, Baptists, Episcopalians, Lutherans, Mennonites, Presbyterians, Assemblies of God, and so on. Again, these folks “protested” the power and practices of the Catholic Church.) As hard as it may be to conceptualize, technological changes allowed for religious change, which allowed for ideological change, which allowed, ultimately, for political change…. POLITICAL REFORMATION With renewed vigor of spirit, humankind entered the Renaissance, looking beyond the Bible for explanations of life. New medical practices, new understandings of human physiology and anatomy, and a willingness to go beyond Biblical explanations for the design of the universe led to great leaps forward in our knowledge base. But perhaps most incredible of all is the leap forward in political thinking. While clearly such did not occur overnight, the idea of representative democracy emerges at the end of the agricultural/beginning of the industrial era. Writes Henslin: “When the United States was founded, for example, this idea (of universal citizenship) was still in its infancy. Today it seems inconceivable to us that anyone on the basis of gender or race/ethnicity should not have the right to vote, hold office, make a contract, testify in court, or own property. For earlier generations of Americans, however, it seemed just as inconceivable that the poor, women, African Americans, Native Americans, and Asian Americans should have such rights” (bottom of 288 to top of 289). SUMMARY Get it? We can’t have a change in one institution without forcing changes in the others. We couldn’t have had a revolution in political thinking were it not for a renaissance in scientific and artistic reasoning. We couldn’t have had a renaissance in scientific thinking had it not been for the disempowerment of the Catholic Church (who had, for example, imprisoned Copernicus for life for suggesting that the earth revolved around the sun, not vice versa). And we couldn’t have had a renaissance in church power had it not been for the power of the printing press. And on it goes. Ain’t life grand????