Sihyun Kim Dr. John Silva English 102.0841

advertisement

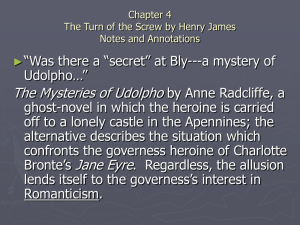

Sihyun Kim Dr. John Silva English 102.0841 4 June 2006 Objectivity versus Subjectivity: The Importance of Both the Heart and Mind in Human Rationale At a quick glance, the governess in Henry James’s “The Turn of the Screw” and the Lawyer in Herman Melville’s “Bartleby the Scrivener” seem to have nothing in common. While the governess is presented as a young woman who is greatly driven by her romantic ideals, the Lawyer is shown as a gentleman whose outlook on life is not cluttered by an overtly active sense of imagination. Nevertheless, when these characters are faced with the task of rationalizing the strange behavior of others in their respective worlds, their minds miserably fail them in the same way: the governess’s extreme subjectivity disastrously thwarts her attempts at saving the lives of those who are closest to her at Bly whereas the Lawyer’s ardent adherence to reason and logic prevents him from properly diagnosing Bartleby’s perplexing conduct in the office. Ultimately, the fact that these seemingly opposite characters fall into similar traps in their “readings” of human beings should demonstrate just how dangerous a blind adherence to either the heart or the mind — but never both — can truly be. In “The Turn of the Screw,” the readers are introduced to a young woman who is eagerly adjusting to her new life at Bly. In her excitement, the governess quickly accustoms herself to her new home by absorbing in as many details as possible, and, curiously enough, one of the first things that she notices are “the long glasses in which, for the first time, [she] could see [herself] from head to foot” (James 30). According to James’s scholar Sheila Teahan, there are two main ways of interpreting her encounter with the mirror: (1) after leading an impoverished life in the countryside, the governess is utterly shocked by the relative luxury of her new home; or (2) in accordance with Lacan’s theory of the mirror stage, the governess has finally recognized that she is an autonomous being who is separate from her father (Teahan 351). Regardless of the interpretation the readers may adopt, one thing, though, is certain: having finally escaped her staid and humble life, the governess is quite eager to begin a new one in which she is urgently needed by others. As a result, it is not surprising that the governess adopts a highly romanticized outlook on her responsibilities at Bly. Indeed, when she first realizes that something is amiss at Bly after stumbling upon the ghostly apparition of Quint, her employer’s former valet, she ponders, “Was there a ‘secret’ at Bly — a mystery of Udolpho or an insane, an unmentionable relative kept in unsuspected confinement?” (41). By comparing her situation to those found in these two quintessentially gothic novels, the governess naïvely concludes that her position can serve her as a possible platform through which she can advance her life (after all, governesses tended to be dowerless women who had little prospects for marriage) by winning her employer’s approval (Teahan 354). However, these romanticisms that the governess exhibits are anything but harmless: they will hereafter disastrously clutter her abilities to logically formulate her surroundings. In sharp contrast to the romantic governess, the Lawyer in “Bartleby the Scrivener” is an ardent pragmatist who heavily relies on reason. He views everything in terms of its practicality and, as a result, has developed an extremely systematic — almost mechanical — outlook on life that is not cluttered by imagination (Gupta 66). This particular attitude that the lawyer exhibits is such a fundamental aspect of his being that it essentially permeates the story. For instance, the way in which the lawyer begins his narration bears strong resemblance to a legal document rather than a personal account: “Ere introducing the scrivener, as he first appeared to me, it is fit I make some mention of myself, my employées, my business, my chambers, and general surroundings; because some such description is indispensable to an adequate understanding of the chief character about to be presented” (107). Before embarking upon his main story, the lawyer meticulously lays out — like all men in his profession generally do — all the “givens” in preparation for the case that he will eventually make in his narration. Given that his story is ultimately about Bartleby, a man whom he hires to copy important documents, and his tragic slide into catatonia, the Lawyer surprisingly remains very objective to his own story, possibly concluding that, in doing so, he will remain free from any implication. Nevertheless, according to the critics R. K. Gupta, it is this tendency to “look upon [reason and common sense] as infallible guide[s] to human conduct” that leaves him ill prepared to properly diagnose anything contrary to logic (Gupta 66). Thus, it is no surprise that, when something that utterly defies reason in the form of Bartleby enters his life, the meticulousness by which the Lawyer lives his life will devastatingly fail him. In short, despite the fact that the governess in “The Turn of the Screw” and the Lawyer in “Bartleby the Scrivener” allegorically represent the two extremes in human judgment — subjectivity versus objectivity — the truth is that their failures to harmoniously incorporate elements from the full range of human rationale deprive them in the same way of what little control they have of their surroundings. In “The Turn of the Screw,” for example, the governess’s intense romanticisms inadvertently trap her in a frenzy of becoming the “heroine” of the story. Upon her realization that Flora and Miles — the children who are placed in her care at Bly — may not be as innocent as they appear, the governess immediately views herself as their possible savior. This glorified perception of her responsibilities cannot be better demonstrated than through the conclusions that she draws after reading a letter regarding Miles’s recent expulsion from school: “They go into no particulars. They simply express their regret that it should be impossible to keep him. That can have but one meaning.” Mrs. Grose listened with dumb emotion; she forbore to ask me what this meaning might be; so that, presently, to put the thing with some coherence and with the mere aid of her presence to my own mind, I went on: “That he’s an injury to the others.” (34). Without having first gathered concrete facts about Miles — a boy to whom she has not yet been properly introduced — the governess lets her active sense of imagination run wild, thereby causing her to formulate a long list of misdeeds with which Miles could have been involved (Teahan 355). Her tendency to overtly dramatize her situation is, without a doubt, the biggest blemish in her character, and it this romanticism that ultimately prevents her from ever diagnosing the true cause behind what she perceives as the children’s “corruption.” Thus, the fact that the governess quickly loses control over the children should not be alarming: because of her intense subjectivity, she can never hope to be the heroine that she has hoped to become. Likewise, the Lawyer in “Bartleby the Scrivener” has exclusively depended on logic to the point that it has left him altogether unable to deal with the unexplainable. Certainly, applying reason in his life has never failed him before — after all, the Lawyer has somehow succeeded in bringing two wholly dysfunctional scriveners, Turkey and Nippers, harmoniously together under his supervision (112) — and, for this reason, the Lawyer understandably assumes that every problem can be handled in similar fashion (Gupta 66). Therefore, when Bartleby astonishingly replies, “I would prefer not to,” after he has been asked to assist in the examination of documents, the Lawyer naturally finds himself thunderstruck with dismay: “Prefer not to,” echoed I, rising in high excitement, and crossing the room with a stride. “What do you mean? Are you moon-struck? I want you to help me compare this sheet here — take it,” and I trust it towards him . . . I looked at him steadfastly. His face was leanly composed; his gray eye dimly calm. Not a wrinkle of agitation rippled him. Had there been the least uneasiness, anger, impatience or impertinence in his manner; in other words, had there been any thing ordinarily human about him, doubtless I should have violently dismissed him from the premises (115). The truth that the Lawyer consistently fails to understand in his narration is that not everything in life can be broken down by logical analysis. Bartleby is a clear example of a man whose behavior cannot be understood by reason alone; yet, the Lawyer’s incapacity for imagination is such an integral part of his rationale that he has allowed his mind to fall into “a groove [that] it cannot easily get out of” (Gupta 67). Instead of getting into the heart of the matter, the Lawyer essentially exacerbates his situation with Bartleby by viewing the problem in terms that are the most convenient for him. For instance, when Bartleby again refuses to perform the duties that are expected of him a few days later, the Lawyer resorts to diplomacy in order to help him acquiesce to his demands: “These are your own copies we are about to examine. It is labor saving to you, because one examination will answer for your four papers. It is common usage. Every copyist is bound to help examine his copy. Is it not so? Will you not speak? Answer!” (Melville 116). His seemingly pragmatic demand for “common usage” is, without a doubt, not the proper manner by which the Lawyer should deal with Bartleby’s compulsive refusal. Nevertheless, because of his inherent inability to “break out of his routine and think in unaccustomed ways,” the Lawyer is forever doomed to misdiagnose the true cause behind Bartleby’s catatonia (Gupta 67). Thus, the Lawyer’s later belief that he has tried everything within his power to rescue his employee is subject to much scrutiny: had he had the imagination and intuition to see beyond Bartleby’s external eccentricities, the Lawyer might have been able to prevent the disaster that is about to come. To a certain extent, it can be inferred from both “The Turn of the Screw” and “Bartleby the Scrivener” that the “misreadings” of the stories’ respective narrators lead to the ultimate deaths of Miles and Bartleby. In “The Turn of the Screw,” for example, the governess is so eager to rise up as the heroine of the story that she frequently goes beyond what is appropriate in her attempts at discovering anything incriminating in the behavior of Flora and Miles. Indeed, the rationale with which the governess tries to carry out her mission is quite illogical to the point of being downright nonsensical: The more I’ve watched and waited the more I’ve felt that if there were nothing else to make it sure it would be made so by the systematic silence of each. Never, by a slip of the tongue, have they so much as alluded to either of their old friends, any more than Miles has alluded to his expulsion. (James 76) Whether the ghostly apparitions of Quint and Jessel are real at this point in the story is irrelevant; the fact that the governess views the children’s silence as the tell-tale proof of their “corruption” should clearly demonstrate that her failures as a “reader” of human conduct can have severe consequences if they are left unchecked (Teahan 356). Unfortunately, as Teahan suggests, this is exactly what happens by the story’s conclusion: [Miles’s] death literalizes a series of metaphors of grasping, seizing, embracing, gripping, taking hold, and the like — locutions that play on the etymological meaning of “comprehend,” which contains a dead metaphor of seizing hold . . . The governess’s reading of the events at Bly is repeatedly figured in these terms: she claim to have found “horrible proofs. Proofs, I say, yes — from the moment I really took hold” (p. 53); struggles to keep Mrs. Grose “thoroughly in the grip” of the conviction that Jessel’s ghost has appeared (p. 59); gets “hold of still other things” from the children’s “systematic silence” (p. 76); and when she asks Miles what happened at school, she discerns “a small faint quaver of consenting consciousness — it made me drop on my knees beside the bed and seize once more the chance of possessing him” (pp. 94-95). (Teahan 358) Given the governess’s tendencies to “take hold” of her surroundings in her attempts at understanding them, it seems quite fitting for her to “hold” Miles “to [her] breast, where [she] could feel in the sudden fever of his little body the tremendous pulse of his little heart” (117) when he begins to reveal what she perceives to be as the cause of his “corruption” (Teahan 358359). But as she repeatedly has demonstrated throughout her narration, the governess once again fails to truly “grasp” what is going on — after all, she misses the significant difference between “everything” and “anything” when Miles tells her shortly before this scene, “I’ll tell you everything . . . I mean I’ll tell you anything you like.” (116): My eyes were now, as I held him off a little again, on Miles’s own face, in which the collapse of mockery showed me how complete was the ravage of uneasiness . . . “And you found nothing [in the letter]!” — I let my elation out. He gave the most mournful, thoughtful little headshake. “Nothing.” “Nothing, nothing!” I almost shouted in my joy. “Nothing, nothing,” he sadly repeated. I kissed his forehead; it was drenched. “So what have you done with it?” (117-118). In her desperate efforts to finally touch upon what has tormented her throughout the narration, the governess tragically fails to notice the immense physical toil that she is wreaking upon little Miles. In other words, the governess is ultimately responsible for his fall by relentlessly using him as a “readable text” with which she can “take hold” of the truth behind the “corruption” at Bly (Teahan 359). As Teahan succinctly states: “In short, she reads him to death” (Teahan 359). In similar fashion, the Lawyer’s failure as a “reader” of Bartleby’s behavior can, in a way, be attributed to the scrivener’s fall at the end of the story. For one thing, despite his projected eagerness in deciphering Bartleby’s bewildering behavior in the office, the Lawyer, in reality, never makes the wholehearted effort to do so: Poor fellow! Thought I, he means no mischief; it is plain he intends no insolence; his aspect sufficiently evinces that his eccentricities are involuntary. He is useful to me. I can get along with him. If I turn him away, the chances are he will fall in with some less indulgent employer, and then he will be rudely treated, and perhaps driven forth miserably to starve. Yes. Here I can cheaply purchase a delicious self-approval. To befriend Bartleby; to humor him in his strange willfulness, will cost me little or nothing. (118-119) Because reason has failed him in his understanding of Bartleby, the Lawyer decides to cease further inquiries by prematurely concluding that his employee’s eccentric behavior is involuntary. But what he does not realize is that Bartleby’s ailment is incurable “only in terms of the palliatives that the narrator, with his limited vision, can think of” (Gupta 68). In short, contrary to what he may say later on in the story (“I had now done all that I possibly could . . .” (139)), the Lawyer, in reality, never makes the sincere attempt at treating Bartleby’s problem. Indeed, the Lawyer’s unwillingness to find a proper “cure” is blatantly clear when he decides to relocate his office in order to rid himself of Bartleby: On the appointed day I engaged carts and men, proceeded to my chambers, and having but little furniture, every thing was removed in a few hours. Throughout, the scrivener remained standing behind the screen, which I directed to be removed the last thing. . . . “Good-bye, Bartleby; I am going — good-bye, and God some way bless you; and take that,” slipping something in his hand. But it dropped upon the floor, and then — strange to say — I tore myself from him whom I had so longed to be rid of. (136) If one were to assume that the “something” that the Lawyer gives Bartleby is money (after all, charity is certainly not contrary to his character), his “remedy” for the scrivener’s catatonia is clearly nothing but a half-measure. (Gupta 68). By this point in the story, the Lawyer should realize that he is placed in a reason-defying situation, and, therefore, must be open to the idea of looking at the problem through a new perspective if he were genuinely concerned about treating Bartleby. Nevertheless, the truth is that the Lawyer, because of his inabilities to “think outside the box,” essentially abandons the scrivener at the end of his narration, thereby inadvertently triggering the chain of events that will lead to his death in prison. In the end, the short stories “The Turn of the Screw” and “Bartleby the Scrivener” collectively serve to show just how dangerous a mind that dwells on absolutes can truly be. Whereas “The Turn of the Screw” illuminates the unreliability of a governess who is irrationally driven by romanticisms, “Bartleby the Scrivener” demonstrates the close-mindedness of a lawyer who simply cannot make a decision without having reason as his guide. When these seemingly incompatible works of literature are viewed side by side, they ultimately show the readers that one cannot depend on either logic or intuition alone in the formulation of his or her surroundings. On the contrary, as the authors of these two stories may suggest, a person in tune with his or her heart and mind can accomplish a much greater deal than those who blindly adhere to extremes. Works Cited Gupta, R. K.. “‘Bartleby’: Melville’s Critique of Reason.” Indian Journal of American Studies (4.1-2) (June and December) 1974: 66-71. James, Henry. The Turn of the Screw. Ed. Peter G. Beidler. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2004. Melville, Herman. “Bartleby the Scrivener.” Billy Budd and Other Tales. Ed. Frederic Barron Freeman. New York: Signet Classic. 107-143. Teahan, Sheila. “‘I caught him, yes, I held him’: The Ghostly Effects of Reading (in) The Turn of the Screw.” The Turn of the Screw. Ed. Peter G. Beidler. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2004. 349-363.