The Field Experience Journal Volume 8 Fall 2011

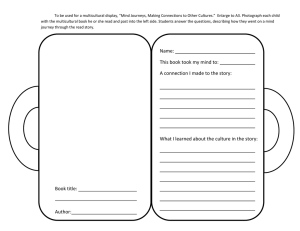

advertisement