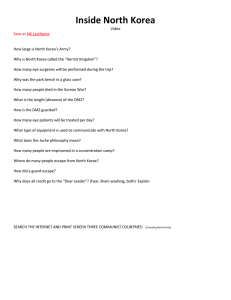

An Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights

advertisement