ENERGY Between Cheap Gas And Carbon Caps, Oil Sands Face Uncertain... Updated December 15, 20151:36 PM ET Published December 14, 20154:52...

advertisement

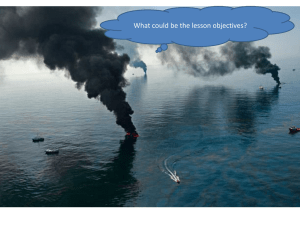

ENERGY Between Cheap Gas And Carbon Caps, Oil Sands Face Uncertain Fate Updated December 15, 20151:36 PM ET Published December 14, 20154:52 AM ET JEFF BRADY Shell's Jack Pine Mine near Fort MacKay, Alberta. The largest trucks, called "heavy haulers," can hold 400 tons of oil sands material. It takes 2 tons to produce one barrel of oil. Jeff Brady/NPR Canada has the world's third-largest oil reserve, and it's worth hundreds of billions of dollars. Nearly all of that crude is contained in Alberta's oil sands. Getting the oil from underground and into your car requires an extraordinary mining effort that has significant effects on the environment and is expensive. In a world concerned about climate change and in which oil prices have plummeted, the oil sands industry faces an uncertain future. http://www.npr.org/2015/12/14/459336339/between-cheap-gas-and-carbon-caps-oil-sands-face-uncertainfate?sc=17&f=1001&utm_source=iosnewsapp&utm_medium=Email&utm_campaign=app 1 Economic, Environmental Concerns Threaten Future Of Oil Sands Stand on the edge of Shell's Jackpine Mine near Fort MacKay, Alberta, and all the senses are occupied: This time of year, it feels very cold outside. There's a faint smellof oil in the air; you get why critics call these "tar sands." And you can hear the constant hum of huge shovels filling massive trucks. But it's what you see that's overwhelming: a very large strip mine. This used to be a dense forest. Now it's a 20-square-mile hole in the ground. "We're running the largest trucks in the world," says Luke Killam, senior adviser for asset operations at Shell Albian Sands. i Ainslie Campbell, environmental sustainability manager for Shell's oil sands operation, demonstrates a device to keep migrating birds out of grimy water that collects at reclamation sites. Jeff Brady/NPR The tires on these "heavy haulers" are 13 feet tall. While most trucks have a few steps for a driver to get into the cab, this one has a staircase. Shell has more than five-dozen of these trucks here hauling 400 tons of earth away at a time. And that's just one company. There are others operating in northern Alberta, such as Suncor and Syncrude. The Alberta government requires companies to fill in these open pit mines and reclaim the land for nature. That can take more than a decade after a mine closes. Companies say they've learned a lot in recent years about how to do that process better, but it still comes http://www.npr.org/2015/12/14/459336339/between-cheap-gas-and-carbon-caps-oil-sands-face-uncertainfate?sc=17&f=1001&utm_source=iosnewsapp&utm_medium=Email&utm_campaign=app 2 with environmental risks. For example, companies have to keep migrating birds out of grimy water that collects at reclamation sites. They use hazing systems with fake birds of prey and air cannons. Some companies are able to produce this crude without strip mining by injecting steam underground. That method presents its own environmental challenges. The Carbon Cost Of Turning 'Play-Doh' Oil Into Fuel Beyond these issues, all oil sands companies face one big environmental challenge connected to climate change: Producing this crude emits more greenhouse gases than traditional drilling. That's because when the oil sands are mined rom the ground, they're not yet ready to be refined into gasoline. Technically, what comes out of the ground is called bitumen; in its raw state, it feels like sandy Play-Doh. An up-close look at oil sands. Oil sands come out of the ground with the consistency of sandy Play-Doh. Only 10 to 13 percent of the gunky ball is actual bitumen. Upgrading it to oil requires additional processing, creating more of the pollution that causes climate change than traditional drilling. Jeff Brady/NPR Even separated from the sand, it's very thick. "The bitumen in its pure form is extremely high in viscosity. It's more viscous than molasses," Killam says. The bitumen has to be diluted with hot water and chemicals so it can be piped about 300 miles south to a plant called an "upgrader" near Fort Saskatchewan. Only then does it become the type of oil that can be refined into fuel for your car. All this extra work requires more energy and releases more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere than a barrel of oil produced in Texas or in Saudi Arabia. That fact is a major focus for oil sands critics. "The tar sands are one of the largest climate polluters in Canada," says Mike Hudema, climate and energy activist for Greenpeace Canada. Hudema is among those campaigning to keep this oil in the ground to address climate change. http://www.npr.org/2015/12/14/459336339/between-cheap-gas-and-carbon-caps-oil-sands-face-uncertainfate?sc=17&f=1001&utm_source=iosnewsapp&utm_medium=Email&utm_campaign=app 3 "Canada needs to do its part. We need to be an active and progressive player, and what that means is that we need to stop the expansion," he says. Keeping Carbon Underground Activists have celebrated a few victories recently. Last month, President Obamarejected the Keystone XL pipeline, which would have transported oil sands crude from landlocked Alberta to the U.S. Gulf Coast, giving producers access to the world market. Another victory for environmentalists came when Alberta Premier Rachel Notley announced that her government will limit carbon emissions from the oil sands business at 100 million tons a year. That could put a damper on the industry's projected growth and prevent Alberta from taking full advantage of its huge oil reserve. That is, unless companies can figure out how to develop the resource and prevent carbon pollution. Shell believes it has a solution. In November, Shell CEO Ben van Beurden was among dignitaries who turned a big, yellow ceremonial valve to mark the opening of the Quest carbon capture and storage project. It captures about one-third of the carbon dioxide emissions from Shell's oil sands upgrader plant. Then the company injects that CO2 deep underground so it stays out of the atmosphere. The Shell Quest carbon capture and storage project near Fort Saskatchewan, Alberta, is designed to capture about one-third of emissions from a plant that upgrades bitumen from oil sands to crude oil. Dignitaries turn a ceremonial valve to mark the official operation of the Quest project. "Canada and Shell have some very good reason to feel some pride in Quest, and we invite the world to follow," van Beurden said at the opening ceremony. http://www.npr.org/2015/12/14/459336339/between-cheap-gas-and-carbon-caps-oil-sands-face-uncertainfate?sc=17&f=1001&utm_source=iosnewsapp&utm_medium=Email&utm_campaign=app 4 Van Beurden says Shell will share what it has learned from building Quest, and says projects like this will get cheaper as they're replicated. Right now, though, capturing and storing carbon is expensive. Quest was built with about $630 million in government subsidies. Because oil prices plummeted over the past year, companies are looking for ways to save money, not spend more. Making A Profit — Barely Lower oil prices also present an economic challenge for Canada's oil sands business. This crude is some of the most expensive oil in the world to produce, since it has to be mined and processed before it's refined. Shell responded to lower oil prices by trimming expenses in its oil sands business up to 30 percent. The company placed limits on overtime, cut back on how long contractors remain on-site and shut down a subsidized Tim Horton's restaurant, a Canadian institution famous for coffee and doughnuts, at its mine site. i Mayor Melissa Blake, Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo, says the area's growth has slowed amid falling oil prices. Jeff Brady/NPR "It's probably the hardest decision we had to make," Donna Kett, finance manager for Shell Albian Sands, says with a laugh. The cost-cutting worked. Shell is producing oil sands crude for about $25 a barrel now. At current prices, that leaves some room for profit — but not much. http://www.npr.org/2015/12/14/459336339/between-cheap-gas-and-carbon-caps-oil-sands-face-uncertainfate?sc=17&f=1001&utm_source=iosnewsapp&utm_medium=Email&utm_campaign=app 5 Cutbacks like these have been felt in nearby Fort McMurray, says Melissa Blake, mayor of the Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo, a sprawling area that includes Fort McMurray. "The rate of growth that we had experienced was anywhere from 7 to 10 percent for every year in the past 15 years," Blake says. Now she says it's down to about 4 or 5 percent. An aerial view of a new housing development near Fort McMurray, Alberta, Canada, in June. Economic activity has slowed in the area, but local residents are optimistic that the energy sector will rebound. Ben Nelms/Bloomberg via Getty Images The Official Outlook: Optimism Locals say restaurants aren't as busy as they were a few years back when the oil sands business was booming. But residents are optimistic about the future. "The oil sands always bounce back," says Allison Frenette, a student at Keyano College studying environmental technology. But not everyone is convinced that's the case. The environmental and economic challenges facing Canada's oil sands business may end up working in favor of those who want this crude left in the ground. "Some portion of oil reserves — perhaps a third — can never be produced, given the need to address the global warming problem," says Philip Verleger, an energy economist who owns an independent consulting firm. Verleger describes a race among oil reserve owners to get their crude out of the ground before the world decides no more can be produced. And that race favors those with the cheapest oil. http://www.npr.org/2015/12/14/459336339/between-cheap-gas-and-carbon-caps-oil-sands-face-uncertainfate?sc=17&f=1001&utm_source=iosnewsapp&utm_medium=Email&utm_campaign=app 6 "If I have $3 [per barrel] costs or $2 costs — as they do in the Middle East — that oil is going to flood the market and essentially make it impossible to make money in Fort McMurray," Verleger says. It's a race he says Canada's oil sands business can't win. That kind of thinking is not popular in Alberta, where officials prefer optimism. Asked about the challenges facing the oil sands business, Alberta Energy Minister Margaret McCuaig-Boyd says, "I think with good old Alberta innovation, we're going to come through and be able to manage it." For now production is continuing at about 2.3 million barrels a day. But the growth in that number has slowed, and companies are canceling expansion plans. Shell halted its Carmon Creek project in October, a decision that will cost about $2 billion. Mayor Blake says the oil sands business is vital to Fort McMurray, which now has about 77,000 residents. She says many families, like her own, moved here for the financial security that comes with working in the oil sands business. Just a few years ago, that looked like a sure way for many to improve their lives. But now the future of the oil sands business is less clear. http://www.npr.org/2015/12/14/459336339/between-cheap-gas-and-carbon-caps-oil-sands-face-uncertainfate?sc=17&f=1001&utm_source=iosnewsapp&utm_medium=Email&utm_campaign=app 7