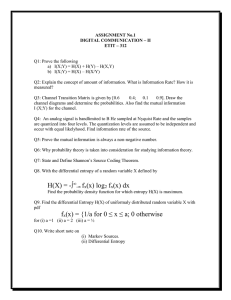

“A” students work (without solutions manual) ~ .

advertisement

“A” students work

(without solutions manual)

~ 10 problems/night.

Dr. Alanah Fitch

Flanner Hall 402

508-3119

afitch@luc.edu

Office Hours Th&F 2-3:30 pm

Module #20

Spontaneity

Effect of number of

Possible configurations

(randomness) on reactions

What we’ve Learned So Far

Energy

Ea

Ea

endothermic

exothermic

A+B

C + heat

A + B + heat

C

rate k A B

Ea

RT

rate A exp A B

Does not tell us if spontaneous or not

A messy room is more probable than an organized

one.

Can think of this as

stored energy.

spontaneous?

or probable?

Spontaneous Reactions:

heat

or

randomness

-heat

+randomness

reactants

-heat

+ randomness

products

-H

+S

OJO

Randomness = more possibilities = entropy (S)

What is the most probable

configuration for n tossed

quarters?

1 coin =2 sides

2 coins

1

2

1

Most probable configuration is least

organized

2 configurations =21

4 configurations =22

What will the pattern be for three coins?

1

3

3 coins

8 configurations = 23

4 coins

? configurations = 2?

#configurations 2 n

3

1

1. Most probable configuration

is least organized

2. Number of possible

configuration increases

exponentially

3. No. configurations contains

information about compound

(sides)

Probability of finding

An electron – everywhere!

Very random

How does this affect

the trends in entropy of

various elements?

1s electron

2p electron probability

Is more confined – less

Random, less entropy

Probability of

Finding an electron

For a d orbital –

More spatially constrained,

Less entropy

Entropy and Atomic Mass

Entropy of Pure Elements

row 2

90

3

4

80

Entropy (J/mol-K)

70

60

50

40

1.

30

20

2.

10

Entropy contraction across row

– related to organization of

electrons

Entropy increase down group –

related to volume occupied

0

0

10

20

30

40

50

Atomic Number

Half filled d

60

70

80

90

Entropy and Group

Group 1

Li

Na

K

Rb

Cs

S (J/mol-K)

29.09

51.45

64.67

76.78

85.5

Group 2 S (J/mol-K)

Be

9.44

Mg

32.51

Ca

41.4

Sr

54.392

Ba

63.2

Group 4 S (J/mol-K)

C

2.43

Si

18.7

Ge

42.42576

Sn

44.7688

Pb

68.85

What do you observe?

Entropy in a Single Group

90

Same observations!

Group 1 (Li to Cs)

Group 2 (Be to Ba)

Group 4A/14 (C to Pb)

80

70

o

S (J/mol-K)

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

0

1

2

3

4

Row of Periodic Table

5

6

7

“A” students work

(without solutions manual)

~ 10 problems/night.

Dr. Alanah Fitch

Flanner Hall 402

508-3119

afitch@luc.edu

Office Hours Th&F 2-3:30 pm

Module #20

Spontaneity

Reaction Entropy

The change in entropy in a reaction is the

difference between the summed entropy of the

products minus the summed entropy of the

reactants scaled by the number of moles

Srx

nS

i

products

i

nS

i

reac tan ts

i

Example Calculation 1: Calculate the change in

reaction entropy that occurs for each of the

following two phase changes given the data below:

1.

Css

Cs

2

Cs

Cs g

Srx

nS

i

products

i

Cs(s)

Cs(l)

Cs(g)

nS

i

reac tan ts

So (J/mol-K)

85.15

92.07

175.6

i

J

J

1moleCss 8515

Srx 1moleCs 92.07

.

molCs K

molCss K

J

J

J

Srx 92.07 8515

.

6.92

K

K

K

Example Calculation 1: Calculate the change in

reaction entropy that occurs for each of the

following two phase changes given the data below:

1.

Css

Cs

2

Cs

Cs g

Srx

nS

i

products

Srx 1moleCsg

i

Cs(s)

Cs(l)

Cs(g)

nS

i

reac tan ts

So (J/mol-K)

85.15

92.07

175.6

i

J

J

175.6

1moleCs 92.07

molCsg K

molCs K

J

J

J

Srx 175.6 92.07 8353

.

K

K

K

Spontaneous Reactions:

heat

or

randomness

-heat

Reactions

+randomness

Increase the

Spontaneity

By an increase

reactants

products

In randomness

-heat

+ randomness

-H

+S

H2O(l)

H2O(g)

Hg(l)

Hg(g)

So (J/mol-K)

69.91

188.83

“Medicine is the Art of

Observation” (Al B. Benson)

What do you observe?

77.40

174.89

Entropy Changes of Cs With Phase

200

160

140

o

85.15

92.07

175.6

S (J/mol-K)

Cs(s)

Cs(l)

Cs(g)

180

120

100

80

60

40

20

0

solid

1. Large change liquid to gas

2. S depends on Temp!!!

liquid

gas

Some typical Standard S values

Element

Ag

Ag+

AgBr

AgCl

AgI

AgNO3

Ag2O

Al

Ba

Ba2+

BaCl2

BaCO3

BaO

Br2

BrC

CCl4

ChCl3

CH4

C2H2

C2H4

C3H8

CH3OH

C2H5OH

CO

CO2

CO32-

form

s

aq

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

aq

s

s

s

l

aq

s

l

l

g

g

g

g

l

l

g

g

aq

S kJ/K-mol

0.0426

0.0727

0.1071

0.0962

0.1155

0.1409

0.1213

0.0283

0.0628

0.0096

0.1237

0.1121

0.0704

0.1522

0.0824

0.0057

0.2164

0.2017

0.1862

0.2008

0.2195

0.2699

0.1268

0.1607

0.1976

0.2136

-0.0569

Element

Ca

CaCl2

CaCO3

CaO

Ca(OH)2

CaSO4

Cd

Cd2+

CdCl2

CdO

Cl2

ClClO3ClO4Cr

CrO42Cr2O3

Cr2O72Cu

Cu+

Cu2+

CuO

Cu2O

CuS

Cu2S

CuSO4

F2

form

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

aq

s

s

g

aq

aq

aq

s

aq

s

aq

s

aq

aq

s

s

s

s

s

g

S kJ/K-mol

0.0414

0.1046

0.0929

0.0398

0.0834

0.1067

0.0518

-0.0732

0.1153

0.0548

0.223

0.0565

0.1623

0.182

0.0238

0.0502

0.0812

0.2619

0.0332

0.0406

-0.0996

0.0426

0.0931

0.0665

0.1209

0.1076

0.2027

Element

FFe

Fe2+

Fe3+

Fe(OH)

Fe2O3

Fe3O4

H2

H+

HBr

HCl

HCO3HF

HI

HNO3

H2O

H2O

H2O2

H2PO4HPO42H2S

H2SO4

HSO4Hg

Hg2+

HgO

I2

form

aq

s

aq

aq

s

s

s

g

aq

g

g

aq

g

g

l

g

l

l

aq

aq

g

l

aq

l

aq

s

s

S kJ/K-mol

-0.0138

0.0273

-0.1377

-0.3159

0.1067

0.0874

0.14645

0.1306

0

0.1986

0.1868

0.0912

0.1737

0.2065

0.1556

0.1887

0.0699

0.196

0.0904

-0.0335

0.2057

0.1569

0.1318

0.075

-0.0322

0.0703

0.1161

Element

IK

K+

KBr

KCl

KClO3

KClO4

KNO3

Mg

Mg2+

“Medicine is the Art of Observation”

Let’s rearrange to make this a little easier

form

aq

s

aq

s

s

s

s

s

s

aq

S kJ/K-mol

0.1113

0.0642

0.0642

0.0959

0.0826

0.1431

0.151

0.133

0.0327

-0.1381

Element

C

Cr

Fe

Al

Mg

Cu

CaO

Ca

Ag

CuO

Cd

CdO

Ba

K

CuS

HgO

BaO

form

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

average

S kJ/K-mol

0.0057

0.0238

0.0273

0.0283

0.0327

0.0332

0.0398

0.0414

0.0426

0.0426

0.0518

0.0548

0.0628

0.0642

0.0665

0.0703

0.0704

0.0446

Element

Cr2O3

KCl

Ca(OH)2

Fe2O3

CaCO3

Cu2O

KBr

AgCl

CaCl2

CaSO4

Fe(OH)

AgBr

CuSO4

BaCO3

CdCl2

AgI

I2

Cu2S

Ag2O

BaCl2

KNO3

AgNO3

KClO3

Fe3O4

KClO4

form

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

average

S kJ/K-mol

0.0812

0.0826

0.0834

0.0874

0.0929

0.0931

0.0959

0.0962

0.1046

0.1067

0.1067

0.1071

0.1076

0.1121

0.1153

0.1155

0.1161

0.1209

0.1213

0.1237

0.133

0.1409

0.1431

0.14645

0.151

0.11139

Element

CCl4

CHCl3

H2O2

C2H5OH

H2SO4

HNO3

Br2

CH3OH

Hg

H2O

form

l

l

l

l

l

l

l

l

l

l

average

0.15112

Pure Liquid

Element

C3H8

Cl2

C2H4

CO2

HI

H2S

F2

C2H2

HBr

CO

H2O

HCl

CH4

HF

H2

form

g

g

g

g

g

g

g

g

g

g

g

g

g

g

g

Solids

Gas

Do we notice anything?

1. More atoms = more S

average

2. Pure liquids higher S than s

3. Aqueous species can have neg S! Why?

4. Gas highest S

S kJ/K-mol

0.2164

0.2017

0.196

0.1607

0.1569

0.1556

0.1522

0.1268

0.075

0.0699

S kJ/K-mol

0.2699

0.223

0.2195

0.2136

0.2065

0.2057

0.2027

0.2008

0.1986

0.1976

0.1887

0.1868

0.1862

0.1737

0.1306

0.20026

Element

Cr2O72ClO4ClO3HSO4IHCO3H2PO4BrAg+

K+

ClCrO42Cu+

Ba2+

H+

FHg2+

HPO42CO32Cd2+

Cu2+

Fe2+

Mg2+

Fe3+

form

S kJ/K-mol

0.2619

0.182

0.1623

0.1318

0.1113

0.0912

0.0904

0.0824

0.0727

0.0642

0.0565

0.0502

0.0406

0.0096

0

-0.0138

-0.0322

-0.0335

-0.0569

-0.0732

-0.0996

-0.1377

-0.1381

-0.3159

average

0.021092

aq

aq

aq

aq

aq

aq

aq

aq

aq

aq

aq

aq

aq

aq

aq

aq

aq

aq

aq

aq

aq

aq

aq

aq

Aqueous

Prediction reactions

producing more

Gas phase species

will increase in

entropy

Possible configurations?

solid < glass, plastic, liquid < gas

Ssolid < Ssolid, plastic,liquid

< Sgas

S

Note: this

Refers to a single

Molecule or element

Water ice, liquid, gas

Absolute

Zero, no motion

T (K)

A closely related idea to change in entropy

In phase changes is the change in entropy in

Going from individual ligands to chelates

From Module 18 we considered the electrostatic

attraction between the electron pairs on ligand

functional groups and the positive nucleus of a

metal ion.

Module 18 review

q1q2

E el k

r

r

1 2

Cu( NH )

3 4

z

x

y

Module 18 review

2

Krx K f 1 K f 2 K f 3 K f 4 K f 5 K f 6 ....... K fn

We observed that multidentate ligands had very high

Kf values

Lead Complexation

Constants

Ligand

logK1

F1.4

Cl1.55

Br1.8

I1.9

OH6.3

Acetate

2.7

Oxalate

4.9

Citrate

5.7

EDTA

17.9

logK2

1.1

0.6

0.8

1.3

4.6

1.4

1.9

LogK3

logK4

-0.4

-0.1

0.7

2

-0.7

-0.3

0.6

Which are polydentate?

What do you observe?

Module 18 review

logKf

2.5

1.05

2.2

4.5

12.9

4.1

6.8

5.7

17.9

Why so large?

Example 2: Predict the entropy change in the following reaction by

considering volume occupied and number of possible configurations

between the reactants and products

Note that the electrostatic attraction which shows up in the enthalpy

is similar for both compounds

M NH2 CH3 4 X 2 2en

M en 2 X 2 4 NH2 CH3

NH 2 CH 3

Example 2: Predict the entropy change in the

following reaction by considering volume occupied

and number of possible configurations between the

reactants and products

M NH2 CH3 4 X 2 2en

M en 2 X 2 4 NH2 CH3

5

3

o

S exp

Cd NH 3 CH 3 4 2en Cd en

2

2

2

4 NH 3 CH 3

J

79.5

mol K

o

S calc

J

58.5

mol K

J. Chem. Ed. 61,12, 1984, Entropy Effects in Chelation Reactions, Chung-Sun Chung

Example Calculation 3: Calculate the reaction

entropy changes for the reaction shown below given:

So (J/mol-K)

S

rhombic

S

orthoclinic

Cu(s)

CuS(s)

Cu2S(s)

32

33

85.15

92.07

175.6

CuS s Cus Cu2 S s

First let’s think about this a bit

1. Internal Entropy

a.Why should CuS have

more entropy than Cu?

b. Why should Cu2S have

much more entropy than

CuS?

CuS s Cus Cu2 S s

Which one might have

More configurations?

http://www.haraldthielenredlich.onlinehome.de/k

kch/cu1+cu2s.jpg

http://images.google.com/imgres?imgurl=http://www.unisa.edu.au/synchrot

ron/res/projects/chalcociteCu2S.jpg&imgrefurl=http://www.unisa.edu.au/sy

nchrotron/res/projects/default.asp&h=242&w=180&sz=20&hl=en&start=7

&um=1&tbnid=UYBN7p1lBciHwM:&tbnh=110&tbnw=82&prev=/images

%3Fq%3DCu2S%2B%26svnum%3D10%26um%3D1%26hl%3Den%26cli

ent%3Dfirefox-a%26channel%3Ds%26rls%3Dorg.mozilla:enUS:official%26sa%3DG

A single, individual, H atom can occupy 4

Different locations – thus the compound will be

CH4

C2H4

So (J/mol-K)

186.

219.4

More random than one with three locations for

The hydrogen

This reflects internal entropy which often scales

with # of Atoms in the molecule.

Example Calculation 3: Calculate the reaction

entropy changes for the reaction shown below given:

So (J/mol-K)

CuS s Cus Cu2 S s

2

1

First let’s think about this a bit

2. Spatial Volume of rx

entropy

Which will be more imp in rx

entropy? Internal entropy

or spatial volume entropy?

We take two separate chemical units and make

Them into 1 chemical unit – implies decrease in

entropy

S

rhombic

S

orthoclinic

Cu(s)

CuS(s)

Cu2S(s)

32

33

85.15

92.07

175.6

Example Calculation 3: Calculate the reaction

entropy changes for the reaction shown below given:

So (J/mol-K)

S

rhombic

S

orthoclinic

Cu(s)

CuS(s)

Cu2S(s)

32

33

85.15

92.07

175.6

CuS s Cus Cu2 S s

Srx

nS

i

products

J

Srx 1moleCus Ss 175.6

molCus Ss K

J

1moleCuS

1moleCus 8515

.

s

molCus K

i

nS

i

reac tan ts

i

J

92.07

molCuSs K

J

J

J

Srx 175.6 8515

.

92.07

K

K

K

Example Calculation 3: Calculate the reaction

entropy changes for the reaction shown below given:

So (J/mol-K)

S

rhombic

S

orthoclinic

Cu(s)

CuS(s)

Cu2S(s)

32

33

85.15

92.07

175.6

CuS s Cus Cu2 S s

2

J

J

J

Srx 175.6 8515

.

92.07

K

K

K

J

J

J

Srx 175.6 177.22 162

.

K

K

K

1

Example Calculation 4: Calculate the change in

entropy for the allotropic forms of elemental S

So (J/mol-K)

S

rhombic

S

orthoclinic

Cu(s)

CuS(s)

Cu2S(s)

32

33

85.15

92.07

175.6

Gr: allos = others

S s , r hom bic S s,orthoclinic

“A” students work

(without solutions manual)

~ 10 problems/night.

Dr. Alanah Fitch

Flanner Hall 402

508-3119

afitch@luc.edu

Office Hours Th&F 2-3:30 pm

Module #20

Spontaneity

Entropy of the surroundings

Spontaneous Process: Universal entropy increases

(The universe is winding down.)

Stotal ( universe) S system ( chemical rx ) S surroundings

S universe 0 spon tan eous

Example 1: Ssurroundings

Cs O2, g CO2, g heat

Change in Ssurroundings?

Change in Sreaction?

More organized (fewer molecules)

implies less entropy, less random

Sreaction <0

heat will

increase

kinetic

energy of

gases =

Ssurround >0

Example 2: Ssurroundings

From surroundings, withdraw heat,

Less kinetic energy, less motion, less entropy

H2 O heat H2 Og

H2 Og

H2 O

+ heat

Although this process requires

heat, it is spontaneous, driven

by entropy of chemical reaction

Reaction less random

rx more random

The two reactions (the system)

Cs O2, g CO2, g heat

H2 O heat H2 Og

Interact with the surroundings by exchange of heat

Heat of reaction must be related to entropy of

surroundings

“A” students work

(without solutions manual)

~ 10 problems/night.

Dr. Alanah Fitch

Flanner Hall 402

508-3119

afitch@luc.edu

Office Hours Th&F 2-3:30 pm

Module #20

Spontaneity

Randomness of the

“surroundings” affected

By enthalpy

Stotal ( universe) S system ( chemical rx ) S surroundings

S surroundings Hreaction

related to enthalpy

or heat of reaction

proportional

Where will impact on Ssurroundings be greatest?

a.

1 J at 600oC

b. 1 J at 25oC

Predict entropy change is largest at low temperatures

Ssurroundings as T

S surroundings

S surroundings

H reaction

T

H reaction

T

sign change accounts for the

fact that entropy increases with

exothermic reactions

Context Slide for a calculation on entropy of the

surroundings

Historically Ag was mined as Ag2S found in the presence of PbS, galena.

Part of the process of releasing the silver required oxidizing the galena.

The lead oxide recovered was used in glass making. The

fumes often killed animals near by and have left a permanent record in

the artic ice. Large regions near silver mines were deforested.

One reason that this process was discovered so early in history was

The low temperature at which it could be carried out.

Lead in Artic Ice

Who has the “honor” of most contaminating

Medicine is the art

The artic ice?

of observation

Calculating Ssurrounding Example 1

2 PbS s 3O2, g 2 PbOs 2SO2, g

Compare the change in entropy of the surroundings for

this reaction at room temperature and at the

temperature of a campfire (~600 oC).

Know:

reaction

o

T 25 C

o

T 600 C

S surroundings

HO

Don’t know

entropy

H reaction

T

o

n

H

f , products

o

n

H

f ,reac tan ts

red herrings?

none

2 PbS s 3O2, g 2 PbOs 2SO2, g

Substance

O2(gas)

PbS

PbO

SO2(gas)

HO

n H

Hf0 (kJ/mole)

0

-100

-219

-297

o

f , products

n H

o

f ,reac tan ts

297 kJ

219 kJ

2moleSO

H 2mole PbOs

2,g

mole

PbOs

moleSO2 , g

O

0kJ

100kJ

3moleO

2mole PbSs

2,g

mole PbSs

moleO2 , g

H O 438kJ 594kJ 200kJ

H O 1032 200 832kJ

S surroundings

H reaction

T

S surroundings

832kJ

T

Calculating Ssurrounding Example 1

2 PbS s 3O2, g 2 PbOs 2SO2, g

Compare the change in entropy of the surroundings for

this reaction at room temperature and at the

temperature of a campfire (~600 oC).

S surroundings

T 25o C

SSsurroundings

surroundings

298

298

T

T 600 C

T 873K

o

T 298K

832

832kJ

kJ

832kJ

2.792kJ

SSsurroundings

surroundings

832

832kJ

kJ

873

873

0.953kJ

Our prediction was right! S surroundings Larger at low T

“A” students work

(without solutions manual)

~ 10 problems/night.

Dr. Alanah Fitch

Flanner Hall 402

508-3119

afitch@luc.edu

Office Hours Th&F 2-3:30 pm

Module #20

Spontaneity

Total Entropy change

With reaction enthalpy

Stotal ( universe) S system ( chemical rx ) S surroundings

S surroundings

H reaction

T

Stotal ( universe) S system ( chemical rx )

Hchemical rx

T

Reaction Entropy Example Calculation 3 Compare

the total entropy change for the following reaction at

25oC and 600oC

2 PbS s 3O2, g 2 PbOs 2SO2, g

Substance

O2(gas)

PbS(solid)

PbO(solid)

SO2(gas)

S0 (J/K-mole)

205 Srx ni S o i , products ni S o i ,reac tan ts

91

66.5

248

J

J

2moleSO2 248

S rx 2mole PbO 66.5

K mol PbO

K molSO2

J

J

3 MoleO2 205

2mole PbS 91

K moleO2

K mole PbS

Reaction Entropy Example Calculation 3 Compare

the total entropy change for the following reaction at

25oC and 600oC

2 PbS s 3O2, g 2 PbOs 2SO2, g

Srx

o

n

S

i i , products

o

n

S

i i ,reac tan ts

J

J

2moleSO2 248

S rx 2mole PbO 66.5

K mol PbO

K molSO2

J

J

3 MoleO2 205

2mole PbS 91

K moleO2

K mole PbS

J

J

Srx 143 496

K

K

J

J

182 615

K

K

J

S rx 168

K

Stotal ( universe ) S system ( chemical rx )

S reaction

J

168

K

832kJ

T

832kJ

T

T 600 o C

T 25 C

o

J

J

S 168 2,791

K

K

J

S 2623

K

Spontaneous

T

S surroundings

Stotal ( universe ) 168 J

J 832kJ

Stotal ( universe) 168

K

298K

J

kJ

S total ) 168 2.791

K

K

Hchemical x

Stotal ( universe)

S total )

J 832kJ

168

K

873K

J

kJ

168 0.953

K

K

S total

S total

J

J

168 953

K

K

J

785

K

Less spontaneous

“A” students work

(without solutions manual)

~ 10 problems/night.

Dr. Alanah Fitch

Flanner Hall 402

508-3119

afitch@luc.edu

Office Hours Th&F 2-3:30 pm

Module #20

Spontaneity

“Free energy” is a

Way of accounting

For contribution of randomness

Hchemical

H

chemicalr xx

Ssystem

SStotal

T

total( (universe

universe)) S

system((chemical

chemicalrx

rx))

T

T Stotal ( universe) T S system ( chemical rx ) Hchemical rx

T Stotal ( universe) Hchemical rx T S system ( chemical rx )

Define

T S total ( universe ) G free energy rx

G free energy Hr x T Srx

Gibb’s free energy

G free energy 0

a) enthalpy of bonds

b) organization of atoms Spontaneous reaction

c) randomness of surroundings

Galen, 170

Marie the Jewess, 300

Charles Augustin

James Watt

Coulomb 1735-1806 1736-1819

Justus von

Thomas Graham

Liebig (1803-1873 1805-1869

Ludwig Boltzman

1844-1906

Gilbert N

Lewis

1875-1946

Henri Louis

LeChatlier

1850-1936

Johannes

Bronsted

1879-1947

Jabir ibn

Hawan, 721-815

Luigi Galvani

1737-1798

Richard AC E

Erlenmeyer

1825-1909

An alchemist

Count Alessandro G

A A Volta, 1747-1827

James Joule

(1818-1889)

Henri Bequerel

1852-1908

Lawrence Henderson

1878-1942

Galileo Galili Evangelista Torricelli

1564-1642

1608-1647

Amedeo Avogadro

1756-1856

Rudolph Clausius

1822-1888

Jacobus van’t Hoff

1852-1911

Niels Bohr

1885-1962

John Dalton

1766-1844

William Thompson

Lord Kelvin,

1824-1907

Johannes Rydberg

1854-1919

William Henry

1775-1836

Johann Balmer

1825-1898

J. J. Thomson

1856-1940

Erwin Schodinger Louis de Broglie

1887-1961

(1892-1987)

Fitch Rule G3: Science is Referential

Jean Picard

1620-1682

Jacques Charles

1778-1850

Francois-Marie

Raoult

1830-1901

Heinrich R. Hertz,

1857-1894

Friedrich H. Hund

1896-1997

Daniel Fahrenheit

1686-1737

Max Planck

1858-1947

Rolf Sievert,

1896-1966

Blaise Pascal

1623-1662

Georg Simon Ohm

1789-1854

James Maxwell

1831-1879

Robert Boyle,

1627-1691

Isaac Newton

1643-1727

Michael Faraday

1791-1867

B. P. Emile

Clapeyron

1799-1864

Dmitri Mendeleev

1834-1907

Svante Arrehenius

Walther Nernst

1859-1927

1864-1941

Fritz London

1900-1954

Wolfgang Pauli

1900-1958

Johannes D.

Van der Waals

1837-1923

Marie Curie

1867-1934

Anders Celsius

1701-1744

Germain Henri Hess

1802-1850

J. Willard Gibbs

1839-1903

Fritz Haber

1868-1934

Thomas M Lowry

1874-1936

Werner Karl Linus Pauling Louis Harold Gray

1905-1965

Heisenberg 1901-1994

1901-1976

Conceptually:

G free energy Hr x T Srx

H reaction

+

+

Sreaction

+

+

-

G free energy 0

Spontaneous?

always

at high T, 2nd term lg.

at lowT, 2nd term sm

never

Gibbs Free Energy Example 1

When will this reaction be spontaneous, hi or lo T?

2 PbS s 3O2, g 2 PbOs 2SO2, g

G free energy Hr x T Srx

H rxO

832 kJ

H reaction

+

+

Srx

168 J

Sreaction

+

+

-

Spontaneous?

always

at high T, 2nd term lg.

at lowT, 2nd term sm

never

At LowT!!!

200

Non Spontaneous Reaction

Free Energy >0

Free Energy (kJ)

0

-200

-400

More

spontaneous

-600

Spontaneous Reactions

Free Energy <0

Can we figure

Out exactly at what T

this reaction becomes

Spontaneous?

-800

-1000

0

1000

2000

3000

4000

5000

6000

7000

KC

o

2 PbS s 3O2, g 2 PbOs 2SO2, g

G free energy

J

832 kJ T 168

K

To find when a reaction will just go

Spontaneous (or not)

1. Use the equation:

G free energy Hr x T Srx

2. Set Go to zero (equilibrium)

0 Hr x T Srx

3. Solve for T.

T Srx Hr x

Tbecomes spon tan eous

Hr x

S rx

4. Depending upon sign of enthalpy entropy

determine if temperature decrease/increase

causes Go to go negative

Gibbs Free Energy Example 2

At what T will this reaction become change between

Spontaneous and non-spontaneous?

2 PbS s 3O2, g 2 PbOs 2SO2, g

G free energy Hr x T Srx

G free energy

J

832 kJ T 168

K

J

0 832 kJ T 168

K

J

832 kJ T 168

K

832 kJ

T

kJ

0168

.

K

4952K T

Rx spontaneous at T<4952K

Gibbs Free Energy Example 2: The only good substitute for PbCO3 for

white paint is TiO2. To manufacture this paint need to be able to process

titanium ore TiO2. (Different allotrope). At what temperature does the

following reaction become spontaneous?

TiOs 2Cs Ti s 2COg

Substance

Tisolid

CO(gas)

TiO2(solid)

O2(gas)

SO2(gas)

Csolid

Hf0 (kJ/mole) S0(J/K-mole)

485

179.45

-110.5

198

-945

50

0

205

-297

248

0

0

G free energy Hr x T Srx

Substance

Tisolid

CO(gas)

TiO2(solid)

O2(gas)

SO2(gas)

Csolid

Hf0 (kJ/mole)

485

-110.5

-945

0

-297

0

S0(J/K-mole)

179.45

198

50

205

248

0

TiOs 2Cs Ti s 2COg

G free energy Hr x T Srx

kJ

..55kJ

kJ kJ 0kJ

485

kJ

110

.5kJ

945

485

110

945

485

kJ

485

kJ

110

kJ

G free energy 111mole

mole

1mole

2

mole

mole

mole

1mole

mole mole 222

mole

mole

mole

mole

mole

mole

mole

mole

mole

mole

.45.45

J J

198

J J

J J

179

179

198

5050

0J

T T1mole

1

mole

2

mole

2

mole

1

mole

1

mole

2

mole

KK

mole

mole

KK

mole

mole

KK

mole

mole

K mole

G free energy 485 221 945 kJ

T 575 50

G free energy

J

K

J

1652 kJ T 525

K

Substance

TiO2solid

Ti

O2(gas)

SO2(gas)

Csolid

CO(gas)

Hf0 (kJ/mole)

-945

485

0

-297

0

-110.5

S0(J/K-mole)

50

179.45

205

248

0

198

TiOs 2Cs Ti s 2COg

G free energy Hr x T Srx

G free energy

J

1652 kJ T 525

K

When is this reaction spontaneous:

at high or low temp?

T 3144 K

0 1652 T 0.525

Rx spontaneous > 3144K

T 0.525 1652

Context Slide 1

WWII

titanium was not routinely processed until

after WWII (jet engine technology). So TiO2 purified

not available cheaply for paint until after WWII

“A” students work

(without solutions manual)

~ 10 problems/night.

Dr. Alanah Fitch

Flanner Hall 402

508-3119

afitch@luc.edu

Office Hours Th&F 2-3:30 pm

Module #20

Spontaneity

Reference states for

Free Energy

As for enthalpy and entropy, there are tables

Of values obtained via Hess’s Law

G,orx

o

n

G

i f ,i , products

o

n

G

i fi ,reac tan ts

f means formation at standard state 25 oC!!!!!

Properties and Measurements

Property

Size

Volume

Weight

Temperature

Unit

m

cm3

gram

Reference State

size of earth

m

mass of 1 cm3 water at specified Temp

(and Pressure)

oC, K

boiling, freezing of water (specified

Pressure)

amu

(mass of 1C-12 atom)/12

atomic mass of an element in grams

atm, mm Hg

earth’s atmosphere at sea level

1.66053873x10-24g

quantity

mole

Pressure

Energy, General

Animal hp

heat

BTU

calorie

Kinetic J

Electrostatic

electronic states in atom

Electronegativity F

horse on tread mill

1 lb water 1 oF

1 g water 1 oC

m, kg, s

1 electrical charge against 1 V

Energy of electron in vacuum

As for enthalpy and entropy, there are tables

Of values obtained via Hess’s Law

G,orx

o

n

G

i f ,i , products

o

n

G

i fi ,reac tan ts

f means formation at standard state 25 oC!!!!!

State of Matter

Standard (Reference) State

Solid

Liquid

Gas

Solution

Elements

Pure solid

Pure liquid

1 atm pressure

1 M concentration

Gfo0

Gibbs Standard Free Energy Example Calc. 1:

What Is the standard free energy change of the

following Reaction? 2 PbS s 3O2, g 2 PbOs 2SO2, g

Substance

PbO

SO2(gas)

PbS

O2(gas)

Grxo

Gf 0 (kJ/mole)

-188.9

-300

-99

0

o

n

G

i f ,i , products

o

n

G

i fi ,reac tan ts

kJ

kJ

G 2moles PbO 188.9

2molesSO2 , g 300

moles PbO

moleSO2

o

rx

kJ

kJ

3moleO 0

2moles PbSs 99

2,g

mole PbSs

moleO2 , g

Gibbs Standard Free Energy Example Calc. 1:

What Is the standard free energy change of the

following Reaction? 2 PbS s 3O2, g 2 PbOs 2SO2, g

kJ

kJ

G 2moles PbO 188.9 moles 2molesSO2 , g 300 mole

PbO

SO2

kJ

kJ

3moleO 0

2moles PbSs 99

2,g

mole PbSs

moleO2 , g

o

rx

Grxo 377.8kJ 600kJ

198kJ

Grxo 779.8kJ

Gibbs Standard Free Energy Example Calc. 1:

What Is the standard free energy change of the

following Reaction? 2 PbS s 3O2, g 2 PbOs 2SO2, g

Grxo

o

n

G

i f ,i , products

o

n

G

i fi ,reac tan ts

Grxo 779.8kJ

For comparison, we calculated from before:

Hrx 832 kJ

G free energy

G free energy

J

S rx 168

K

J

832 kJ T 168

K

J

832 kJ 298 K 168

K

G free energy 782kJ

Not too bad of

Agreement!

“A” students work

(without solutions manual)

~ 10 problems/night.

Dr. Alanah Fitch

Flanner Hall 402

508-3119

afitch@luc.edu

Office Hours Th&F 2-3:30 pm

Module #20

Spontaneity

Summing Reactions

Rx#

1

A+B

2

nC + D

nC

E

3

E

A+B+D

Greaction

Greaction 1

Greaction 2

Greaction 1 + Greaction 2

Summing Free Energy Example Calculation Why

was lead one of the first elements first processed by

man? A. Calculate the standard free energy of the

Combined reactions. B. Calculate the free energy of

the reaction at 600 oC (campfire temp).

2 PbS s 3O2, g 2 PbOs 2SO2, g

2 PbOs 2Cs 2 Pbs 2COg

2 PbS s 3O2, g 2Cs 2 Pbs 2SO2 , g 2COg

Summing Free Energy Example Calculation Why

was lead one of the first elements first processed by

man? A. Calculate the standard free energy of the

Combined reactions. B. Calculate the free energy of

the reaction at 600 oC (campfire temp).

2 PbS s 3O2, g 2 PbOs 2SO2, g

H 832kJ

O

rx

J

S 168

K

0

rx

Grxo 779.8kJ

2 PbOs 2Cs 2 Pbs 2COg

Need standard free energy to solve A

But! Will also need standard enthalpy and S

To solve B – so solve for those

Substance

Pb

CO(gas)

PbS

PbO

O2(gas)

SO2(gas)

Csolid

Hf0 (kJ/mole) S0(J/K-mole)

0

0

-110.5

198

-100

91

-219

66.5

0

205

-297

248

0

0

2PbOsolid + 2Csolid

2Pbsolid + 2CO(gas)

ΔH= [{(2(0)+2(-110.5)}-{2(-219)+2(0)}]=+217kJ

ΔS=[{2(0)+2(198)}-{2(66.5)+2(0)}]=263J/K

?

2 PbOs 2Cs 2 Pbs 2COg

H 217kJ

O

rx

J

S 263

K

0

rx

G free energy Hr x T Srx

G free energy

J kJ

217 kJ T 263 3

K 10 J

At standard conditions

kJ

G 217 kJ T 0.263

K

o

kJ

G 217 kJ (25 273) K 0.263 138.6

K

o

At campfire conditions

kJ

G 217 kJ (873) K 0.263 12.56

K

o

Grxo 138.6kJ

Net reaction at 25 oC

Grx

2PbS(solid) + 3O2(gas)

PbO(solid) + 2SO2(gas)

2PbOsoloid + 2Csolid

2Pbsolid + 2CO(gas)

2PbS + 3O2(gas) + 2Csolid

-779.8 kJ

+138.6kJ

2Pbsolid + 2SO2gas + 2COgas

sum = -641kJ

The net standard free energy for the coupled two

reactions is -641 kJ, spontaneous

Net reaction at 600 oC

2PbS(solid) + 3O2(gas)

PbO(solid) + 2SO2(gas)

2PbOsoloid + 2Csolid

2Pbsolid + 2CO(gas)

2PbS + 3O2(gas) + 2Csolid

Grx

-685 kJ

-12.6kJ

2Pbsolid + 2SO2gas + 2COgas

sum = -697kJ

The reduction of Pb in PbS to metal and oxidation

of S in PbS to sulfur dioxide gas is spontaneous at

campfire temperatures of 600oC

Context point: can manufacture pure lead in a campfire

Context Slide

Where did all the lead go?

Decade

1914-23

1920-29

1930-39

1940-49

1950-59

1960-69

1970-1979

Context Slide

Estimate lbs white lead/housing unit

110

87

TiO2 makes inroads

42

particularly in Europe

22

7

3

White lead restricted

1

2 2

2 2

2 22

5 5

300gPb

gPb

1lbPb

lbPb 12

12

.gsoil

gsoil 228

228

.44

mi

gsoil

1609

.

km

300

1

.

12

.

.

44

mi

1609

.

km

10

10

cm

cm

x

x

x

x

6

3

x

x

x

x

x

x

x3cm 14,790,239lbPb

6 gsoil

3 3

3

45359

gPb cm

10

cm

Chicago

45359

.. gPb

mi

106 gsoil

cm

Chicago mi km

km

300ppm = “background” level of Chicago soil lead

Depth: does

Not move down

Because of Oh Card me PleaSe

Percent of Children with

Elevated Blood Lead Levels

Chicago, 1999

ugPb/gsoil

<250

250-500

500-1000

>1000

N

W

E

S

Percent of Children

with Elevated Blood

Lead Levels

< 5%

5% - 15%

16% - 25%

> 25%

5

0

5 Miles

Context Slide

Relates to

a) Age of Housing

b) “Gentrification”

Relevant Chem 102 Concepts:

1. Temperature dependence

of spontaneous reactions

2. Stability of soil lead form

(Oh Card me PleaSe)

“A” students work

(without solutions manual)

~ 10 problems/night.

Dr. Alanah Fitch

Flanner Hall 402

508-3119

afitch@luc.edu

Office Hours Th&F 2-3:30 pm

Module #20

Spontaneity

Relating Free Energy

To Concentrations

The free energy of the reaction related to

a) standard free energy change

b) and the ratio of concentrations of

products to reactants, Q

G G RT ln Q

o

In this equation you can use (simultaneously)

Pressures

Concentrations

The ln(Q) is treated as unitless

Free Energy and Conc. Example Calc. Calculate the free

energy of the reaction if the partial pressures of the gases are each

0.1 atm, 298 K. Remember, we calculated ΔGrx to be -641 kJ at

298K (25 oC)

2 PbS( s) 3O2 s 2C( s) 2 Pb( s) 2SO2( g ) 2CO( g )

G G RT ln Q

o

Pb 2 P 2 P 2

J

s

SO2 CO

Grx 641kJ 8.314 298 K ln

PbS 2 P 3 C 2

K

s

O2

s

2

2

1 2 PSO

P

CO

2

Grx 641kJ 2477.57 J ln 2 3 2

1 Po2 1

2

2

PSO

P

CO

2

Grx 641kJ 2.47757 kJ ln

3

PO2

01

. 2SO2 01

. 2CO

Grx 641kJ 2.47757 kJ ln

3

. O2

01

Grx 641kJ 2.47757kJ ln 01

.

Grx 641kJ 2.47757kJ 2.302)

Grx 641kJ 5703

. kJ

Grx 647

kJ

mol

When Q = K (equilibrium):

0 G o RT ln K

RT ln K G o

G RT ln K

o

G G o RT ln Q

0

K

At equilbrium no

Energy to drive

Rx one way or other

K=1

-RT ln (1) = 0

K >1

-RT ln (>1) = -(+) < 0

K<1

-RT ln (<1) = -(-) > 0

Example Problem 2 Free Energy and Equilibrium:

What is the equilibrium constant for the reaction

at a campfire temperature?

2 PbS s 3O2, g 2Cs 2 Pbs 2SO2 , g 2COg

G RT ln K

o

G

ln K

RT

o

e

G o

RT

Go = -697kJ/mol rx

kJ

697

mol

Ke

K

kJ

8.314 x103

298 K

mol

K

K e 281 10100

Example 3 Free Energy and Equilibrium:

The corrosion of Fe at 298 K is K = 10261 .

What is the equilibrium constant for corrosion

of lead?

2Pbsolid + O2gas

2PbOsolid

We don’t have any K values so we need

To go to appendix for various enthalpy and

Entropies to come at K from the backside

Substance

PbS

PbO

Pb

O2(gas)

SO2(gas)

Csolid

CO(gas)

Hf0 (kJ/mole) S0(J/K-mole)

-100

91

-219

66.5

0

0

0

205

-297

248

0

0

-110.5

198

2 Pbs O2( g ) 2 PbO

Go = Ho - TSo

Ho = 2(-219) - {2(0) + 2(0)} = -438kJ

So = 2(.0665) - {2(0) + 2(.205)} = -0.277kJ/K

Go = -438 - T(-.277) = -438 - (298)(-0.277) = -355kJ

RT ln K - Go

G 355kJ

kJ

355

mol

Ke

G 0

RT

e

kH

8.314 x103

298 K

mol K

K e143 127 x1062

K for rusting of Fe = 10261

K for rusting of Pb = 1.27x1062

so: even though the reaction is favorable

it is less so than for iron.

Lead rusts less than iron = used for plumbing

“A” students work

(without solutions manual)

~7 problems/night.

Module #20

Spontaneity

What you need to

know

1. Be able to rank the entropy of various phases of

materials, including allotropes

2. Be able to rank the entropy of various compounds

3. Explain entropy concepts as related to chemical

geometry

4. Calc. standard entropy change for a reaction

5. Relate surrounding entropy to reaction enthalpy

6. Calc. temperature at which a reaction becomes

spontaneous

7. Explain why TiO2 was relatively late in replacing

PbCO3 as a white pigment; why lead was one of

first pure metals obtained by humanity

8. Convert standard free energy to equilibrium

constant

“A” students work

(without solutions manual)

~7 problems/night.

Module #20

Spontaneity

END

Entropy and Molecular Structure:

O2(g)

O3(g)

S,J/mol-K

161

205

237.6

C (g)

CO (g)

CO 2(g)

158.O

197.9

213.6

Cl (g)

Cl2(g)

165.2

2232.96

z

Pb

PbO

PbO2

Pb3O4

68.85

68.70

76.98

209.2

z

CH4

C2H4

186.4

219.4

C2H2

C2H4

C2H6

200.8

219.4

229.5

O(g)

z

#configurations z

n

“z” = 2

z

Have we

Convinced

Ourselves

Yet?

“z” = 4

“z” =6

“z” = 8

Internal Entropy and Molecular Structure:

#configurations z

n

Internal Entropy is generally increasing

With number of atoms in the molecule

Because the number of locations within the molecule

Where an atom could be found is increasing and

Because the possible orientations

of the molecule increases

Entropy of various Solids

14

1, average=38.26

12

Number observed

10

8

2, average=62.15

6

3, average = 95.42

4, average=137.9

4

5, average 103

Reliability of average

decreases with number

of averaged data points

2

6, average- 124

0

0

50

100

150

200

Entropy (J/mol-K)

250

300

350