Developing Personal Competencies through Service-Learning: A Role for Student Organizations

advertisement

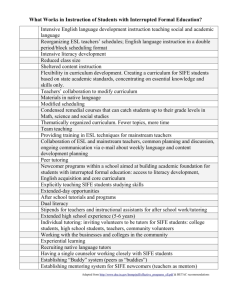

Student Organizations 1 Developing Personal Competencies through Service-Learning: A Role for Student Organizations Gail Lynn Cook Brock University Department of Accounting & Finance St. Catharines, ON L2S 3A1 Canada (905) 688-5550 ext. 3919 (905) 688-9779 fax gcook@taro.bus.BrockU.CA Curtis L. DeBerg California State University – Chico Department of Accounting & Management Information Systems College of Business Tehama 313 Chico, CA 95929-0011 (530) 898-4824 (530) 898-4970 fax cdeberg@csuchico.edu Alfred R. Michenzi* Loyola College in Maryland Department of Accounting Sellinger School of Business & Management Loyola College in Maryland 4501 North Charles Street Baltimore, MD 21210 (410) 617-2752 (410) 617-2006 fax AMichenzi@loyola.edu Bernard J. Milano Executive Director KPMG Foundation Three Chestnut Ridge Road Montvale, NJ 07645 (201) 307-7662 (201) 307-7333 (fax) bmilano@kpmg.com Dasaratha V. Rama Texas A & M International University Department of Accounting & Information Systems College of Business Administration Laredo, TX 78041 (956) 326-2521 (956) 326-2492 fax dvrtamiu@yahoo.com * Contact Author: Professor Alfred R. Michenzi Student Organizations 2 Developing Personal Competencies through Service-learning: A Role for Student Organizations Abstract This paper examines service-learning (S-L) through student organizations as one way to overcome some of the challenges of course-based S-L and to create additional S-L opportunities for accounting students. Student organizations do not provide typical course-based mechanisms such as syllabi, assignments, and grading. Thus we focus on alternative ways to establish and communicate educational outcomes, designing activities to enhance these outcomes, and assessing outcomes. We discuss examples of S-L in three organizations in which many accounting students may participate in (1) Students in Free Enterprise, (2) Beta Alpha Psi, and (3) accounting clubs. Each of these student organizations must address similar issues in terms of developing S-L. However, there are also important differences between these organizations. Thus our examples illustrate how the S-L approach can be adapted to different student organization settings. Student Organizations 3 Developing Personal Competencies through Service-Learning: A Role for Student Organizations Service-Learning (S-L) involves an integration of community service activities and academic study. Rama (1998) describes several approaches for integrating community service activities into a variety of accounting courses. Rama et al. (2000) examine empirical research on S-L outcomes and discuss how course-based S-L projects can be structured to develop a range of complex competencies recommended by various professional groups (e.g., Bedford Committee 1986; Arthur Andersen et al. 1989; AECC 1990; AICPA 2001). In course-based S-L, faculty can structure projects to enhance specific learning outcomes. First, they can select service activities that allow for the application of course material. Second, they can implement assignments that help students connect the service to their coursework. Finally, they can monitor student progress and provide feedback. A key challenge involves finding appropriate service projects that allow students to apply course content in the relatively limited time available during the semester. The time available for project work may be further limited by the time required to help students acquire the necessary background knowledge for technical course-based S-L projects. In this paper, we examine S-L through student organizations as one way to overcome some of the challenges of course-based S-L and to create additional S-L opportunities for accounting students. Our motivation to explore S-L through student organizations results from several reasons. First, there is greater flexibility in selecting projects since service activities do not have to be linked directly to a specific course. Student Organizations 4 Second, community service activities through student organizations and course-based S-L can complement each other in developing various competencies. For example, coursebased S-L may be more suitable for reinforcing course content and for helping students apply course content to complex, unstructured problems. In contrast, student organizations can focus on projects that help students develop a variety of personal competencies such as professional demeanor, teamwork, leadership skills, communication skills, project management skills, and others in the AICPA Core Competency Framework (CCF) (AICPA 2000). Third, S-L in student organizations can enhance personal competencies by providing a structure for sustained involvement by students over longer periods of time than a typical course. While many student organizations may already involve their members in community service, the emphasis of such activities may be on achieving community outcomes. In contrast, the key ideas underlying S-L focus on community service activities that contribute valuable services while simultaneously contributing to students’ educational growth. Thus, the key question we address in this paper is: How can the service activities of student organizations be purposefully structured to enhance educational outcomes for students? We organize the rest of the paper as follows. First, we discuss key design issues in developing S-L in student organizations by highlighting differences between student organizations and course-based projects. The next section provides an example to illustrate how S-L can be implemented in a particular student organization (Students in Free Enterprise - SIFE). The following sections examine S-L in Beta Alpha Psi (BAP) and accounting clubs. The last section offers a summary and discussion. Student Organizations 5 S-L IN STUDENT ORGANIZATIONS This section offers general guidelines on designing S-L for student organizations. We focus on the differences between a typical student organization environment and a classroom environment, and the implications of these differences for the design of S-L activities. S-L Outcomes Student organizations must establish clear educational outcomes for S-L and then identify ways to accomplish these outcomes. Some outcomes are better achieved through course-based S-L. For example, faculty cannot teach specialized accounting knowledge in a student organization setting. However, students can practice the accounting knowledge acquired in courses through S-L activities of student organizations. Accounting programs can develop integrated approaches that link course based S-L with service activities of student organizations. The SIFE example discussed in this paper represents an integrated approach that builds upon the relative strengths of both approaches. Another issue to consider in selecting outcomes relates to the roles of students and faculty in course-based S-L and in student organizations. Organizations such as BAP and SIFE emphasize student ownership of service activities. Project management, communication and leadership outcomes in the AICPA framework are thus particularly well-suited to this environment. Further, such outcomes are probably more easily addressed in student organization settings than in a course. In our SIFE and accounting club examples, students assume project management responsibilities after they have Student Organizations 6 gained some experience for one or two semesters. It may be less feasible to provide students significant project management responsibilities in a brief S-L experience integrated into a course with several other requirements. A final issue that we emphasize relates to the process by which outcomes are established and communicated in student organization settings. In a course, outcomes are communicated through the use of syllabi and assignments. Student organizations do not provide these mechanisms for communicating outcomes and requirements. We identify several alternative communication approaches that are effective in this environment. Service Activities Student organizations must select service activities to support desired educational outcomes. They must also consider the mission of the organization, the interests and skills of students, and the resources available for S-L. Student organizations with members from several disciplines may emphasize service projects that involve broad business knowledge but do not require specialized accounting knowledge (e.g. SIFE). If the members of the student organization are limited to accounting majors, it is possible to focus on accounting-related service projects (e.g. VITA). Structured Reflection Many educators have underscored the importance of reflection in experiencebased pedagogies including S-L, and offered guidelines on designing reflection (Eyler et al. 1996, Rama 2001). We use the term structured reflection to refer to a thoughtfully constructed process that is designed (1) to challenge and guide students in examining critical issues related to their service-learning project, (2) to connect the service experience to business/accounting knowledge, and (3) to develop skills and values. Prior Student Organizations 7 literature has identified several forms of structured reflection including journals, presentations, informal and formal discussions, and integrative papers (Eyler et al. 1996, Goldsmith 1995). In a course setting, faculty can add reflection activities such as journals, end of project papers, and presentations to course requirements. In a student organization setting, we cannot assign papers or other assignments and grade them. Thus, we have to identify other means for incorporating structured reflection into S-L projects. National organizations such as SIFE and BAP provide several opportunities for reflection through the annual report preparation process, regional/national presentations, and mentoring activities. Faculty advisors can also suggest other opportunities for reflection including presentations by professionals/community leaders, informal discussions between students, and meetings between students and faculty. We discuss how each of these activities can be structured to support desired learning outcomes. Assessment Assessment has multiple purposes. One important purpose is to provide feedback to students on what is expected of them, what they have done well, what they need to improve on and how (cf. Learn and Serve America National Service-Learning and Assessment Study Group 1999). Another important purpose of assessment is evaluation, which courses and the related grading typically accomplish. Since course-based mechanisms such as assignments and exams cannot be used we will explore alternative assessment opportunities available in student organization settings. Structured reflection activities conducted on an ongoing basis are key to assessing student progress towards S-L goals and for providing feedback. In addition, Student Organizations 8 regional/national competitions of organizations such as BAP and SIFE provide a formal evaluation mechanism in student organization settings. Whether we consider informal assessments that occur during reflection activities (e.g. student discussions with faculty advisor) or formal external evaluations, most assessment data currently used to evaluate S-L projects lie in the area of authentic assessment. Authentic assessment involves the students in meaningful activities that require high order thinking skills and the coordination of a broad range of knowledge (Hart, 1994). Student organization annual reports, oral presentations, reports from members of the community, and the number of community members who continue to desire the presence of college students in their agencies and schools represent examples of authentic assessment data. In the SIFE and BAP examples, we believe that the final and most important step of authentic assessment consist of students comparing their work with that of their peers at regional and national competitions. The following sections provide examples of S-L SIFE, BAP, and accounting clubs. These examples focus on establishing and communicating outcomes, designing service activities and reflection, and assessing S-L. S-L IN SIFE SIFE is a non-profit educational organization that works in partnership with business and higher education. SIFE provides college students the opportunity to establish community outreach programs that teach others how market economies and businesses operate. Currently, the SIFE organization consists of about 30,000 students at over 1,000 colleges and universities throughout the U.S. and, recently, 20 countries. SIFE Student Organizations 9 is open to all business majors, and it also encourages membership from non-business disciplines. Furthermore, it has no minimum scholastic standards or academic level (although individual SIFE teams may require such standards). SIFE projects can help students improve their understanding of basic business and accounting concepts as well as to develop several personal competencies especially, project management skills and communication skills. The discussion below first explains, in general, how outcomes are established, reflection activities are designed, and how the S-L activity is assessed in the SIFE organization. We then go on to illustrate this process by explaining how one SIFE team from a large public university in California has structured its activities to enhance these outcomes. We use the term SIFE-C to refer to the specific SIFE chapter described in this study in order to distinguish it from the overall SIFE organization. Regional/National Competitions Each spring, SIFE teams compete against one another at one of 20 regional competitions and one national competition throughout the United States, and 19 national competitions in other countries. Regional winners participate in a national competition for U.S. schools. SIFE inaugurates its "World Cup” in London in July 2001. As discussed below, these competitions provide a framework for establishing and communicating outcomes, as well as for assessing S-L in SIFE. S-L Outcomes Table 1 shows the judging criteria for SIFE competitions and relates the criteria to the elements of project management and communication competencies in the AICPA Student Organizations 10 framework. One element of project management identified in the AICPA CCF is the ability to determine project goals. SIFE criteria provide specific guidelines on project goals. A second element involves measuring project success. Judging criterion 5 requires students to measure and document the results of their projects. Another set of elements relates to obtaining and managing resources for a project. SIFE criteria 6 and 7 require students to discuss the utilization of specific resources - Business Advisory Board (BAB), students from non-business disciplines, and mass media and the Internet. TABLE 1 ABOUT HERE Judging criterion 8 relates to communication competencies in the AICPA CCF. The faculty advisor can relate these requirements to the following elements of communication competencies in the AICPA CCF: (1) selects appropriate media for dissemination or accumulation of information, and (2) uses interpersonal skills to facilitate effective interaction. Note that the other elements of communication skills in the AICPA CCF include selecting and organizing relevant information for a given context, and presenting it in a concise and clear manner. Judging criteria 1- 7 offer specific guidance on what kinds of information are appropriate in SIFE reports / presentations. For example, criterion 7 suggests that students must discuss how they utilized the BAB in their projects. Note that to be able to design and execute projects according to criteria 1-4, students need broad business knowledge and basic accounting knowledge. In SIFE-C, students acquire this knowledge and get an initial opportunity for applying this knowledge to a SIFE project in an introductory business or principles of accounting course. Since the business/accounting knowledge required for SIFE projects are acquired Student Organizations 11 through coursework, we do not consider these competencies further in this paper. Rather, we focus on how SIFE-C structured activities that enhance project management and communication skills. To summarize, the judging criteria offer a mechanism for communicating educational outcomes of SIFE projects to students and thus represents the equivalent of a syllabus in a course. The judging criteria also help students understand how their skills will be assessed and thus play a role similar to grading policies/exams in a course. Under an S-L approach, the faculty advisor could discuss how these criteria relate to competencies desired by the accounting profession. Structured Reflection SIFE teams submit an annual report and make a 30-minute multimedia presentation at the competitions. These activities provide opportunities for extensive reflection on SIFE projects. The instructor typically provides report requirements and presentation guidelines in a course project in order to guide student reflection. Similarly, the judging criteria provide direction to student reflection in SIFE. Again, the faculty advisor can enhance the educational value of SIFE projects by relating the annual report and presentation activities to AICPA CCF and other competency definitions. Assessment The regional/national competitions represent a significant opportunity for authentic assessment. Judges at these competitions include nearly 1,000 entrepreneurs, CEOs, and other business leaders. The SIFE home office makes the score sheets and judges comments available to the teams. The structuring of SIFE activities also supports other Student Organizations 12 forms of external assessment. As an example, judging criteria 6 measures students’ effectiveness in utilizing the mass media and the internet. In order to get media attention, SIFE students must practice their communication skills with a different audience, and their success in getting this attention represents another opportunity for external assessment of communication outcomes. SIFE-C Activities The regional/national competitions provide the basic framework for establishing and communicating outcomes, structuring student reflection, and assessing S-L. As noted above, these mechanisms are analogous to syllabi, assignments, and exams in a course. In a course-based project, several additional activities would be required for effective S-L such as lectures and discussions of concepts needed for S-L, team discussions, and interim reviews of student progress. While traditional lecture/discussion methods may not be feasible in student organizations, the SIFE team can structure its routine activities to prepare students for service activities, to support the development of various competencies and to provide feedback. The SIFE-C team uses several such activities. SIFE-C has designed these activities to address the diverging needs of inexperienced and experienced students. Also note that SIFE-C incorporates reflection activities before, during, and after the service experience in order to enhance learning (Eyler et al. 1996, Rama 2001). Meeting with Faculty Advisor The faculty advisor and the SIFE-C team review comments from judges at the SIFE competitions. The team uses this to develop goals and activities for the next year. For example, in the previous year, judges identified project assessment as one area requiring Student Organizations 13 additional attention. Such feedback can enhance students’ project management competencies in several ways. First, it increases their awareness of the importance of assessment. Second, such feedback stimulates additional research and discussion on better ways of assessing outcomes. Third, students have to focus on assessment issues throughout the year. Even as they are setting goals and deciding on projects, they have to devise assessment methods and collect data on an ongoing basis. The faculty advisor can help students’ connect judges feedback and planning process to project management outcomes. Orientation At the beginning of every semester, veteran students organize an orientation session. SIFE officers/project leaders describe SIFE goals, judging criteria, projects, and other activities involving travel and presentations to freshmen/sophomore students. Veteran students get a chance to practice the communication skills. Since students explain SIFE-C projects in terms of judging criteria and goals, the orientation session provides an opportunity to reflect on project management issues as well as the associated communication issues early in the year. At the same time, rookie students can understand SIFE-C activities and educational outcomes. Faculty advisors could encourage veteran students to relate SIFE activities and outcomes to educational goals. Rookie students’ motivation to join may increase if they see the connections between SIFE activities and professional skills. SIFE-C Meetings The SIFE-C President organizes regular meetings with the entire SIFE team as well as meetings with project leaders. These meetings provide extensive opportunities to Student Organizations 14 reflect on project goals, resource generation/utilization, and project progress. Rookie students also benefit from such meetings as it increases their awareness of project management and communication issues, and thus prepares them to assume project management roles in the future. Review Others’ Work One way for students to learn about effective communication is to review annual reports and presentations prepared by other students. Veteran students can review the prior year annual reports, scripts of presentations, and videos of prior year presentations while preparing their own annual report and presentation. For example, the 2001 annual report includes the following sections: History, Profile, Organization, Ethics, Projects, Project Highlights (number of students served, number of hours, project growth from previous years), Linking Projects to judging criteria. By reviewing this report, students in subsequent years can learn how to select appropriate information about their projects and how to organize and present this information. The SIFE-C team also provides opportunities to rookie students to enhance their communication skills. Rookie students can earn bonus points in an introductory business / accounting course by reviewing the current year’s presentation script according to the judging criteria and providing feedback. Students could also be asked to consider competency definitions such as those in the AICPA CCF while reviewing others’ work. Feedback from Faculty/Business Advisory Board To prepare for the regional and national competitions, SIFE students make presentations to faculty and the BAB. The teams uses faculty and BAB feedback to refine Student Organizations 15 the team’s presentation and enhance each students’ oral communication skills. The BAB also helps the SIFE team in identifying the most effective speakers to represent the team in the competitions. Linking SIFE Projects to Courses In addition to the above activities for learning project management and communication skills, SIFE students also have an opportunity to formally acquire these skills through coursework. Students who have demonstrated outstanding leadership skills and commitment to the SIFE-C team can earn 3 hours of credit for a course titled “Technology, Teamwork and Leadership.” The course also includes students from computer science. Students learn skills such as computer animation, scripting, storyboarding, videotaping, and digital photography. These skills are used to develop a 30-minute multimedia presentation for the SIFE competitions. Mentoring and Coaching Others Experienced SIFE teams are encouraged to help other teams by adopting new teams and traveling to their campuses to make presentations to students, faculty, administrators, and business advisers. The team described in this paper has made several presentations on college campuses to describe how to start SIFE teams on their college campus and to help prepare for SIFE competitions. The SIFE team also mentors high schools in starting SIFE teams. Such mentoring makes it feasible for students in new SIFE teams to also acquire the relevant communication skills. At the same time, a larger number of students from experienced teams get opportunities to practice their communication skills. Student Organizations 16 Summary The SIFE example focused on ways in which the activities of a student organization can be structured to enhance educational outcomes. Student organizations should consider the critical importance of establishing and communicating outcomes. Students have to be aware of SIFE criteria, how these relate to specific educational outcomes, and how regional/national competitions will measured these outcomes. Faculty advisors can use the knowledge of outcomes and assessment to help transform the routine activities of the student organization into more reflective educational activities directed towards specific learning outcomes. Authentic assessment data supports the effectiveness of this team’s approach. This SIFE-C team has advanced to the nationals in each of the last 8 years from 1994. In the last three years, this SIFE team was a national champion in one year, and placed in the top 10 and 12 finalists in the other two years. Several other indicators measure the success of the SIFE students in their outreach projects and communicating their activities to various stakeholders. First, more than half the current projects are a continuation of successful projects from prior years. Second, many of the new projects are extensions of successful projects in other communities. For example, a successful program for at-risk high school students has been expanded to two other high schools and has led to the development of a summer program, a program for students on probation and a program for incarcerated youth. Third, the SIFE team has been successful in obtaining funds for its programs. For example, in 2000-2001, the SIFE team obtained $63,000 from the BAB. Finally, the SIFE Student Organizations 17 team has obtained significant media coverage. One example of national press coverage was a magazine article appearing in Entrepreneur magazine (June 2000) entitled “Pass it On” by Victoria Neal. This feature article included SIFE among many of the college and university business programs that are working with youth to help them understand the significance of entrepreneurship and the influence of technology on careers. The SIFE-C team was prominently featured as an example of one outstanding SIFE team. BAP AND ACCOUNTING CLUBS In the next section, we describe S-L projects in two other student organizations, BAP and an accounting club. We focus on the differences arising because of differing missions, membership, and activities of different student organizations. We also use this section to stimulate thinking on service activities that may be appropriate in different contexts. We do not repeat our suggestions for establishing and communicating outcomes, structuring routine activities of the student organization to enhance educational outcomes, and the role of faculty advisors. However, we do note important differences that student organizations must consider in developing an S-L approach. BAP BAP and SIFE provide similar environments for S-L in many ways. Both are national organizations with members from multiple disciplines and various stages of the academic program. Further, BAP chapters can apply for best practices awards in three key areas including service (BAP 2001). Chapters applying for these awards are expected to submit a report that specifies outcomes, number of members participating, member hours, nonmembers involved in the activity and their roles, and an assessment of Student Organizations 18 outcomes. An initial presentation is required at a regional meeting. The BAP Board and National Advisory Forum members evaluate these presentations. These reports and presentations can serve the same role as SIFE competitions in guiding S-L. There are also several differences with implications for S-L in BAP. First, SIFE criteria guide the development of educational outcomes and service activities of individual SIFE chapters. BAP chapters have more flexibility in selecting educational outcomes and service activities, and thus tailor S-L to the needs and interests of a specific chapter. If a chapter consists primarily of accounting majors, it can focus on accounting specific projects. On the other hand, BAP chapters may need to spend more time and effort prioritizing outcomes and activities. The following discussion explains how one chapter in a college in Maryland, developed a pilot S-L implementation. As with the SIFE example, we distinguish between the overall BAP organization and the particular chapter (BAP-M). BAP-M is relatively small and has around twenty-five members and pledges annually. Almost all students live on or very near the campus. The college’s mission supports service to others and offers many opportunities for students to involve themselves in service. Students are generally active in service and embrace these opportunities. S-L Outcomes The first step in developing the pilot was to select appropriate outcomes. For reasons discussed before, BAP-M chose project management as one category of outcomes for S-L. Since BAP’s mission includes developing a commitment to service, Student Organizations 19 lifelong growth, and ethical conduct, BAP-M identified civic engagement as a second relevant outcome for the chapter’s S-L implementation. Service Activities and Reflection The process used to enhance project management was very similar to our SIFE example. The process consisted of (1) an initial meeting between the faculty advisor and students, (2) planning meetings of students only, (3) a discussion of the project plan by the student Vice President and faculty advisor, (4) informal reflection during project execution, and (5) a wrap-up reflection activity (a student self-report). At the initial meeting, the faculty advisor explained the rationale for including project management and civic engagement as outcomes of S-L. To support the civic engagement outcomes, the faculty advisor suggested that the chapter explore opportunities to work with accounting professionals in a service activity. Accounting professionals can serve as role models for students in developing a commitment to service and reinforcing the concept of the profession giving its time and talents back to the community. In addition to an appropriate service activity, the advisor explained the need for structured reflection to support this outcome. In the pilot, the faculty advisor suggested that the chapter organize a presentation by professionals describing their community involvement. The purpose of the presentation was to help students’ understand the civic responsibility of professionals, the benefits of community involvement to themselves, their employers, the profession and the community, and the role of community service activities in supporting lifelong learning. The student Vice President and chapter members then discussed possible projects. One member suggested the Christmas in Spring project, which is sponsored by Student Organizations 20 more than 20 local organizations and corporations. The purpose of the project was to go to a local low-income community and do house repairs, clean up, yard work, painting, and trash removal. BAP-M selected this activity since it involved close cooperation of the students and accounting professionals in the performance of the service activity. Further, BAP-M usually completes a service activity of short duration since many students individually participate in longer service projects. Assessment Since this was a pilot, the focus of the assessment activity was on getting feedback about the S-L approach and how it could be enhanced in the future. Students were impressed by the fact that business professionals spent their time on a weekend participating in these events. Based on student comments, actual participation of professionals seemed to have had a greater impact in helping students think about community involvement than the presentation by a participating professional. In the future, the chapter will continue to explore possibilities for tying in service activities with those of accounting professionals, which will better support reflection activities on community involvement/civic responsibility. Students identified several ways to improve S-L. They underscored the need for planning the project well in advance to ensure that more students can participate. They also suggested that more attention must be paid to planning the details of the service and the communication of these details of the project to all stakeholders. Finally, they suggested that in the future the chapter should identify service activities that match the skills and interests of the members. Students felt that their contribution to the project was limited because they did not have enough experience in home repairs. Student Organizations 21 Accounting Clubs Our final example illustrates how an S-L approach can be implemented in an accounting club. Accounting clubs differ from our earlier examples in two major ways. First, accounting clubs lack the national structure and organization that can guide S-L in SIFE and BAP. Second, accounting clubs may not have a service requirement. Thus, a faculty champion needs to encourage students to adopt S-L. We discuss how these differences affect S-L in an accounting club environment. S-L Outcomes As with BAP, accounting clubs have flexibility in establishing outcomes. Given that accounting clubs usually include only accounting majors, accounting clubs can emphasize projects that require accounting knowledge (e.g. VITA). Since accounting clubs do not have a mechanism such as the judging criteria for SIFE, faculty advisors must also devise a way to communicate educational outcomes to students. Also, accounting clubs starting an S-L program may not get the type of support available to a new SIFE team from more experienced SIFE teams or from the national office. One possibility is for the accounting club to coordinate its’ activities with established programs such as VITA or Junior Achievement (www.ja.org). The accounting club described in this paper is very small with membership varying between 8 and 20 participants per year. The students had strong ties to the local community and a corresponding desire to “give something back.” The faculty advisor suggested S-L projects to the club officers at the yearly organizational meeting. The desired outcomes for these projects included application of business knowledge, civic engagement, small-scale project management, and oral communication. The two projects Student Organizations 22 that the group settled on were volunteering with Junior Achievement (JA) and establishing a Scholastic Book Club (SBC) (www.scholastic.com or www.clubs.scholastic.ca) for the on-campus Child Care Center. These projects were chosen because the faculty advisor had contacts with these two groups and the club could implement the projects in a short period of time. Service Activities and Reflection The general process for these projects consisted of (1) identifying an officer to take a leadership role in overseeing the project, (2) gathering information from JA and SBC, (3) recruiting student volunteers, which included informal reflection activities, (4) informal reflection during a self-assessment as the projects were passed to the next group. To gather information about JA, the local JA representative made a presentation to the accounting club at a meeting that was opened to all business majors. The representative explained that the purpose of JA is to bring business and economics programs into K-12 classes. Specifically, JA recruited university students to teach the grades 5 and 6 programs. A number of students at the meeting had participated in JA as students and spoke about the benefits to students of the programs. Students volunteered either individually or in teams to teach the JA program. JA provided training and all materials for the volunteers. The students were responsible for arranging times (approximately 1 hour a week for 6 weeks) with their assigned classroom teachers, preparing for the session, showing up on time, and teaching the JA lesson. The faculty advisor regularly observed students making plans, discussing their materials, and sharing classroom stories. The positive experiences and benefits of participating in JA were shared each of the next two terms when recruiting new volunteers. Student Organizations 23 The accounting club officer heading the SBC project gathered information from the SBC website, called the customer service representative, and coordinated with the director of the Child Care Center. Each month fliers with short letters explaining the ordering process and due date were distributed to parents; a notice was posted at the Child Care Center; orders and money were collected, recorded, and tallied; orders were placed with SBC; payment was made; and finally books were distributed to the parents. The students reconciled any discrepancies between their record keeping system and the books received. The record keeping system tracked who ordered which books, how many of each book was ordered, bonus books ordered, payments received, and payments made to SBC. This system was continued from the first year’s group to the second year’s group. The first year’s students explained the system to the incoming officers. Although the second group did not have to develop the system, they did have to manage it on a month-by-month basis. Also, they had the opportunity to improve upon it. Assessment Accounting club volunteers covered approximately 12 JA classes during the first year of participation and another 7 classes during the second year (membership in the accounting club was very low in year 2). The local JA office made a donation to the club for each class a student member taught. Students who taught 2 classes in a year were eligible to apply for JA scholarships. Many of the students did teach 2 classes in the year; however, most accounting club members were graduating seniors and could not use the scholarship the following year. The local JA office also collected information from the classroom teachers and student volunteers about the JA experience. All of the feedback about the student volunteers was very positive. Student Organizations 24 The SBC program generated between $7.00 and $30.00 per month in the free books for the Child Care Center. Additionally, the Child Care Center staff accumulated points, which they used to purchase other classroom materials. The parents and staff looked forward to receiving their new flier each month. Although only 2 accounting club students participated each year in this activity, these students did comment positively about the opportunity to manage this small-scale project and apply their knowledge in a limited, manageable setting. This type of project could be expanded into other child care centers or the local elementary schools to provide an opportunity for more students to participate. SUMMARY AND DISCUSSION This paper explored the use of an S-L approach in three types of student organizations in which accounting students participate. Key issues to address in implementing S-L include: (1) establishing outcomes, (2) communicating outcomes, (3) selecting service activities, (4) designing reflection, and (5) assessing S-L. Since mechanisms such as syllabi and grades are not applicable in this environment, we identified other means for addressing these issues. We discussed the key role played by regional/national competitions in each of these areas. Since accounting clubs do not have such competitions, faculty advisors have a critical role in developing the educational potential of service projects. Student organizations should structure routine activities to foster critical reflection on service activities in light of the project’s educational objectives. Examples include: (1) meetings with the faculty advisor, (2) informal discussions among team members, (3) orientation/training sessions conducted by experienced students, (4) presentation by Student Organizations 25 current officers to incoming officers/members on prior year’s goals and activities, progress made and lessons learned, and (5) presentations by professionals/community leaders. Finally, student organizations should explore appropriate assessment techniques. Assessment is crucial for providing feedback and enhancing learning. Regional/national competitions also provide a more formal evaluative assessment similar to grades in a course-based project. Limitations A key challenge in implementing an S-L approach in student organizations involves resource constraints. Student organizations must consider available funds, student time, institutional support, and faculty time. Faculty guidance is critical to enhancing the educational value of service activities. Lack of formal rewards and recognition for faculty may present a major barrier to the adoption of this approach. However, note that faculty time commitment is not as high as in course-based projects since students assume significant responsibility for organizing and managing projects. Further, we believe that this problem is not unique to S-L, and accounting programs must address this systematically as they move from an information dissemination model of teaching to competency driven learning environments. The educational value of S-L will also depend on the type of service activities. Extended service activities (e.g. SIFE example) are more likely to enhance competency development than short-term experiences (e.g. BAP example). Service activities such as VITA allow students to apply course based and/or disciplinary knowledge in addition to developing personal competencies. Further, students must have the opportunity to Student Organizations 26 participate in several additional activities that can enhance their learning from the service activities (project management, communication, travel, and mentoring activities). The service and the associated activities represent a significant time commitment for students. Another challenge involves ensuring that the student volunteers as well as faculty have adequate training in S-L. A major advantage of SIFE is the extensive support available to new teams in developing and implementing S-L. One promising direction for the future development of S-L in student organizations involves coordination across various student organizations. In particular, BAP and accounting clubs can develop partnerships with SIFE teams since SIFE membership is open to students at all stages of their academic program. BAP and accounting clubs can extend the basic community service, project management, and communication experiences obtained from an affiliation with SIFE and develop more specialized skills through their service projects. Finally, S-L through student organizations complements but does not replace coursebased competency development. The lack of mechanisms such as syllabi, lectures, assignments, exams, significant individual feedback, and grades implies that student organizations cannot be the primary means for developing certain competencies. On the other hand, accounting graduates require numerous complex competencies to succeed in their profession. Accounting programs must address the challenge of developing these competencies in the limited time available. Leveraging the existing service activities of student organizations to enhance various competencies thus represents a promising approach for accounting programs. Student Organizations 27 TABLE 1 SIFE Judging Criteria vs. AICPA Core Competencies SIFE Criteria AICPA Core Competency Framework How creative, innovative and effective were the students in teaching: 1. How free markets work in the global economy? 2. How businesses operate by identifying a market need and then profitably producing and marketing a product or service to fill that need? 3. The personal entrepreneurial, communications, technology and financial management skills needed to successfully compete 4. Practicing business in an ethical and socially responsible manner that supports the principles of a market economy. Project Management Determines project goals In their educational programs, how effective were the students at: 5. Measuring the results of their projects. Project Management Measures project progress 6. 7. Utilizing mass media and the Internet. Involving non-business majors and utilizing a Business Advisory Board. Project Management Realistically estimates time and resource requirements Allocates project resources to maximize results Effectively manages human resources that are committed to the project 8. Communicating their program through their written report and verbal presentation. Organizes and effectively displays information so that it is meaningful to the receiving party Expresses information and concepts with conciseness and clarity when writing and speaking. Places information in appropriate context when listening, reading, writing and speaking Selects appropriate media for dissemination or accumulation of information. Uses interpersonal skills to facilitate effective interaction Student Organizations 28 References Accounting Education Change Commission (AECC). 1990. Objectives of education for accountants: Position statement number one. Issues in Accounting Education 5(2): 307-312. American Accounting Association (AAA), Committee on the Future Structure, Content, and Scope of Accounting Education (The Bedford Committee). 1986. Future accounting education: Preparing for the expanding profession. Issues in Accounting Education 1(1): 168-195. American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA). 2000. AICPA Core Competency Framework for Entry into the Accounting Profession. New York, NY: AICPA http://www.aicpa.org/edu/corecomp.htm. Arthur Andersen & Co., Arthur Young, Coopers & Lybrand, Deloitte Haskins & Sells, Ernst & Whinney, Peat, Marwick Main & Co., Price Waterhouse, and Touche Ross. 1989. Perspectives on Education: Capabilities for Success in the Accounting Profession. New York, NY. Eyler, J., D. E. Giles, Jr. and A. Schmiede. 1996. A Practitioner’s Guide to Reflection in Service-Learning: Student Voices and Reflections. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University. Goldsmith, S. 1995. Journal Reflection: A Resource Guide for Community Service Leaders and Educators Engaged in Service-learning. Washington, D. C.: The American Alliance for Rights & Responsibilities. Hart, D. 1994. Authentic Assessment: A Handbook for Educators. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company. Neal, V. 2000. Pass it On. Entrepreneur. 28(6) June: 105-109. Rama, D. V. (ed.) 1998. Learning by Doing: Concepts and Models for Service-learning in Accounting. Washington, DC: American Association for Higher Education. _____. 2001. Using Structured Reflection to Enhance Learning from Service. Providence, RI: http://www.compact.org/disciplines/reflection.