\begindata{text,538986648}

\textdsversion{12}

\template{default}

\define{global

}

\define{footnote

attr:[Flags OverBar Int Set]

attr:[FontSize PreviousFontSize Point -2]}

\define{concat

menu:[Font,Concat]

attr:[Script PreviousScriptMovement Point 6]

attr:[FontSize PreviousFontSize Point 2]}

\define{sans

menu:[Font,Sans]

attr:[FontFamily AndySans Int 0]}

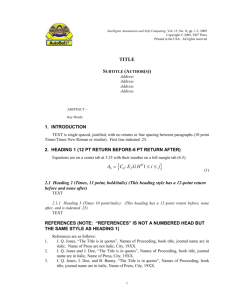

\flushright{16 July 1993 - Ness 2.0}

\majorheading{Ness: A Short Tutorial}

\center{by Wilfred J. Hansen}

\indent{\flushright{\smaller{_________________________________

Andrew Consortium

Carnegie Mellon University

__________________________________

}}

Ness is a programming language for the Andrew ToolKit. With it,

documents

can be processed and can even contain active elements controlled by Ness

scripts. The language features an innovative substring algebra for

string

processing. \

This document is a tutorial description of the language itself. If you

are

familiar with other programming languages, you may still benefit from

reading the sections of this manual that describe the string algebra.

For

a description of other Ness documentation, see \bold{Ness User's Manual}.

1. Program structure

2. String algebra

3. Search

4. Concatenation

5. Replacement

6. An Example

Appendix: $ANDREWDIR/lib/ness/demos}

\bold{

\begindata{bp,539031944}

Version 2

n 0

\enddata{bp,539031944}

\view{bpv,539031944,12,0,0}}

Copyright IBM Corporation 1988, 1989 - All Rights Reserved

Copyright Carnegie Mellon 1993 - All Rights Reserved

\

\smaller{

$Disclaimer:

Permission to use, copy, modify, and distribute this software and its

documentation for any purpose and without fee is hereby granted, provided

that the above copyright notice appear in all copies and that both that

copyright notice and this permission notice appear in supporting

documentation, and that the name of IBM not be used in advertising or

publicity pertaining to distribution of the software without specific,

written prior permission.

THE COPYRIGHT HOLDERS DISCLAIM ALL WARRANTIES WITH REGARD

TO THIS SOFTWARE, INCLUDING ALL IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF

MERCHANTABILITY AND FITNESS. IN NO EVENT SHALL ANY COPYRIGHT

HOLDER BE LIABLE FOR ANY SPECIAL, INDIRECT OR CONSEQUENTIAL

DAMAGES OR ANY DAMAGES WHATSOEVER RESULTING FROM LOSS OF USE,

DATA OR PROFITS, WHETHER IN AN ACTION OF CONTRACT, NEGLIGENCE

OR OTHER TORTIOUS ACTION, ARISING OUT OF OR IN CONNECTION

WITH THE USE OR PERFORMANCE OF THIS SOFTWARE.

$

}

\begindata{bp,539032488}

Version 2

n 0

\enddata{bp,539032488}

\view{bpv,539032488,13,0,0}

Ness programs are a collection of definitions of variables and functions.

For instance:

\example{\smaller{\italic{function} \bold{main}()

\leftindent{printline ("Hello, world")}

\italic{end} \italic{function}}}

When executed, this program will print "Hello, world" in the command

window.

To execute a Ness program from a command window, give the nessrun

command.

If the text above is in file hello.n, the command would be

\example{nessrun hello.n}

Nessrun compiles the program into an internal form and executes it by

calling the function main(). The name \italic{main} is magic--Nessrun

always calls it first. \

If you want to pass parameters to main(), you can write a string after

the

name of the Ness program file:

\example{nessrun hello.n This is a string}

The string after the file name is passed as an argument to main().

access it, main needs to declare an argument:

To

\example{\italic{function} \bold{main}(arg)

\leftindent{printline(arg)}

\italic{end} \italic{function}}

The printed output is a single line saying

\example{This is a string}

Ness programs can do arithmetic.

few

Fibonacci numbers:

Here is a program to print the first

\example{

\italic{integer} \italic{function} \bold{Fibonacci} (\italic{integer} x)

\leftindent{\italic{if} x <= 1 \italic{then} \

\leftindent{\italic{return} x}

\italic{else}

\leftindent{\italic{return} Fibonacci(x-1) + Fibonacci(x-2)}

\italic{end} \italic{if}}

\italic{end} \italic{function}

\italic{function} \bold{main}()

\leftindent{\italic{integer} i

i := 0

\italic{while} i <= 12 \italic{do}

\leftindent{printline(textimage(Fibonacci(i)))

i := i + 1}

\italic{end} \italic{while}}

\italic{end} \italic{function}}

With the above in file /tmp/fib.n, a typical execution would look like

this:

\example{% \bold{nessrun /tmp/fib.n}

Compile okay.

Elapsed time is 4360 msec.

0

1

1

2

3

5

8

13

21

34

55

89

144

Execution okay.

Elapsed time is 280 msec.}

Items to note about the program:

*

Execution begins with a function named 'main'.

* The \bold{for} statement is currently not implemented, so it has to be

simulated with a \bold{while} statement as shown in main().

* Since the Fibonacci function returns an integer value, it cannot be

printed directly; it must be converted to a string value by passing it

to

the function textimage(), which converts any value to an appropriate

string. (Plans are in the works for letting print() and printline()

directly convert integer values to strings.)

* Function arguments and return values are by default subseq values, so

the

types must be explicitly declared \bold{integer} for Fibonacci() and its

argument x.

* The algorithm shown is highly inefficient; consider how many times

Fibonacci(1) is computed. The reader is invited to write and try a

better

version of this program.

\section{1. Program structure}

A Ness script is a sequence of declarations for variables, functions, and

objects to be extended.

Variable declarations begin with the name of the type and then have a

list

of the names of the variables:

\example{\smaller{\italic{subseq} s, p, q

\italic{integer} i, j, count

\italic{real} height, weight

\italic{boolean} FirstTime := \italic{True}}}

These examples include the four most common data

types.\footnote{\

\begindata{fnote,539040600}

\textdsversion{12}

\enddata{fnote,539040600}

\view{fnotev,539040600,14,0,0}In original Ness, subseq variables were

declared with the type 'marker'.} Variables may be initialized in their

declaration, but then there can only be one name in the list.

Function declarations look like this

\example{\smaller{\italic{integer} \italic{function} \bold{square}

(\italic{integer} a)

\italic{return} a*a

\italic{end} \italic{function}}}

The function header gives the type returned by the function, the word

'function', the function name, and a parameter list in parentheses. The

type may be specified as 'void' to indicate that nothing is returned. The

parameter parentheses must appear even if there are no parameters:

\example{\smaller{\italic{void} \italic{function} \bold{main}()

printline(textimage(square(3)))

\italic{end} \italic{function}}}

Program execution begins with the function named 'main'.

two

examples constitute a program which prints '9'.

The preceding

If there are multiple parameters, they are separated with commas and each

must have the type name:

\example{\smaller{real function dist(real a, real b)

return sqrt(a*a + b*b)

end function}}

Between the function header and the 'end function' may appear variable

declarations and statements, but not more function declarations:

\example{\smaller{\italic{void} \italic{function} \bold{quadroots}

(\italic{real} a, \italic{real} b, \italic{real} c)

\italic{real} disc, ba

disc := b*b - 4.0*a*c

ba := b/a/2.0

\italic{if} disc > 0.0 \italic{then}

printline("roots: " \

~ textimage(ba + sqrt(disc)/a/2.0) \

~ " \italic{and} " \

~ textimage(ba - sqrt(disc)/a/2.0))

\italic{end} \italic{if}

\italic{end} \italic{function}}}

\section{2. String Algebra}

String values in Ness are formally known as \italic{subseq} values

because

such a value does not actually denote a string, but rather refers to, or

marks, a substring of an underlying base string. A program can declare

subseq variables:

\example{\smaller{\italic{subseq} s, m}

}

and assign them references to constants:

\example{\smaller{s := "abcdefg"

m := s}}

Now s refers to the entirety of the base string a b c d e f g . And m

refers to the same. This is a fundamental property of assignment of

subseq

values: m \italic{does not} refer to a copy of \typewriter{s}--it refers

to the \italic{same} base string as \typewriter{s}. \

Four primitive functions start(), next(), base(), and extent() are

provided

for manipulating string values. (Many additional functions are defined

in

terms of these primitives.)

\bold{start(x)} - The value of start of x is a subseq refering to a

position between two characters. In particular, the value refers to the

position just before the start of the value referred to by x. Suppose x

refers to the substring c d e of the value a b c d e f g above, then

the value of start of x is a subseq for the empty position between b and

c.

\bold{base(x)} - Returns a subseq for the entire base string of which x

refers to a part. Suppose again that x refers to the substring c d e

of

the value a b c d e f g , then the value of base(x) is a subseq

referring

to the entire value a b c d e f g .

To get an empty mark at the beginning of the underlying base string for

subseq p, you can use the composition of the functions start and base:

start(base(p)).

The opposite composition, base(start(p)), returns

exactly the same value as base(p) because p and start(p) both refer to

the

same underlying base string.

\bold{next(x)} - This function returns a subseq for the character

following the value marked by x. When x is c d e , next(x) is a subseq

for f on the same base string. If the argument x extends all the way to

the end of its base string, then next(x) returns an empty mark for the

position just after the last character of x. \

Now we can write expressions for more interesting subsequences relative

to

a given mark t. The first character \italic{after the beginning of t} is

next(start(t)) because start(t) computes the empty subseq just before the

first character and next() computes the character just after its

argument.

Note the careful inclusion of the phrase "after the beginning of t";

next(start(t)) does not compute the first character of t if t is a

subseq

for an empty substring--such a subseq has no characters and thus

certainly

no first character.

Similarly, the second character after the beginning of a given subseq t

is

next(next(start(t))) and the first character of the base is

next(start(base(t))).

\bold{extent(x, y)}

-

Computes a subseq from two other subseqs on the

same base.

The new subseq value extends from

the beginning of the first argument,

x

to

the end of the second argument,

y.

So if x is c d e in a b c d e f g and y is b c d e f then extent(x,

y) will extend from just before c, the first character of x, until just

after f, the last character of y; the value will be c d e f. The two

arguments need not overlap or even be contiguous; if x is b c and y is

e f the value of extent(x,y) is b c d e f. \

It may be that the first argument of extent() begins after the second

ends.

In this case extent() is defined to return the a subseq for the empty

position just after the \italic{second} argument. Note that this

position

comes \italic{before} the beginning of the first argument.

Another possible problem with the arguments to extent() is that they may

be

on different base strings. In this case, the value returned is a subseq

on

a unique base string whch has no characters.

With the aid of extent() we can write even more useful functions.

Suppose

we really want the first character of a subseq; the result should be

empty

if the argument subseq is empty. We approach indirectly by first finding

an expression for all characters after the first character of a subseq

value. Let t be the subseq value and assume for the moment it has at

least

one character. From earlier work we know that the first character is

given

by next(start(t)) and the character after that by next(next(start(t))).

Now the sequence of all characters after the first character begins with

that second character and extends to the end of t, so we can write the

function rest():

\example{\smaller{\italic{function} \bold{rest}(t)

\leftindent{\italic{return}

extent(next(next(start(t))), t)}

\italic{end function}}}

Now imagine that the argument t for rest() has no characters. The first

argument to the extent function will be a subseq which begins after the

end

of t, the second argument; so the result of the extent() will be the end

of that second argument. But since t is empty, the end of t is identical

to t itself and the function rest() applied to an empty subseq returns a

subseq equal to its argument.

With the aid of rest() we can compute the first character of a subseq:

it

is the subseq which extends from the beginning of the original subseq up

to

the beginning of the rest().

\example{\smaller{\italic{function} \bold{first}(t)

\leftindent{\italic{return} extent(t, start(rest(t)))}

\italic{end function}}}

It may seem inefficient to compute first() and rest() by such round-about

means, and it is. These are simply formal definitions in terms of the

four

primitives start(), base(), next(), and empty(); in practice first() and

rest() can be implemented more efficiently by writing them in the same

low

level language as is used for the primitives.

In Ness we can represent a set as a sequence of its elements and write an

algorithm for all subsets. The result is a sequence of subsets, each in

parentheses. For example, if the input is abc the result is

(abc)(ab)(ac)(a)(bc)(b)(c)():

\example{\smaller{\italic{function} \bold{subsets}(s)

\italic{if} s = "" \italic{then return} "()"

subset

-- the empty

\italic{else} \

\italic{subseq} m := subsets(rest(s))

\

-- m is all subsets of all but first element

\italic{return} combine(first(s), m) ~ m

-- concatenate:

-- all subsets of rest(s) \

--

with first(s) inserted in each

-- and all subsets of the rest(s)

\italic{end if

end function

function} \bold{combine}(t, s)

\italic{if} s = "()" \italic{then return} "(" ~ t

inserted

in empty subset

~

")"

-- t

\italic{else} \

\italic{subseq} m := extent(s, search(s, ")"))

-- first

subset

\italic{return} "(" ~ t ~ rest(m) -- t inserted in first

subset

~ combine(t, allnext(m))

-- t inserted in remaining

subsets

\italic{end if

end function}

}}

The second function, \bold{combine}, takes an element and a sequence of

subsets and forms a new sequence of subsets with the element inserted in

each subset. This is utilized by the first function which initially

splits

its argument into a first element and a remainder, then finds all subsets

of the remainder, and finally concatenates this list of subsets with the

list generated by combining the first element with the subsets from the

remainder.

\section{3. Search}

Search functions in Ness search through the base of their first argument

looking for some substring described by the second argument. The return

value is a subseq referring to a substring of the first argument.

sequence

The

\smaller{\example{\italic{subseq} m := "abcdef"

m := search(m, "cd")

printline(m)}}

will print \bold{cd}, but it will print a copy of the \bold{cd} within

\italic{m}. So if other string operations are applied to the result of

the

search, they will locate other text within \italic{m}. Thus

\smaller{\example{\italic{subseq} m := "abcdef"

\italic{subseq} s

s := search(m, "cd")

printline(extent(next(s), m))

}}

will print \bold{ef}, the characters starting with \italic{next(s)} and

extending to \italic{finish(m)}.

\

By convention, the string searched is delimited by the precise details of

the first argument: If it is a zero-length substring, the search extends

from it to the end of the base; but if non-zero, the search occurs only

within the substring delimited by that first argument. For a search that

does not succeed, the value returned is a zero-length subseq at the

position of the end of the first argument. Thus a first argument of

start(x) differs from one of toend(x) in the location of the empty subseq

returned for a failing search.

Two of the search functions, \italic{search}() and \italic{match}() treat

their second argument as a string to be matched exactly in the first

(white

space and the case of characters must all match exactly). The other

three

treat their second argument as a set of characters. For instance, in the

expression

\example{\smaller{anyof(toend(x), ".?!")}}

the set has three characters and the expression will return a subseq for

the first character in base(x) after start(x) which is a period, question

mark or exclamation point. If there is no such character, the

expression

returns an empty subseq at the end of toend(x), which is the end of

base(x).

\description{\italic{search}(x, pat) - find the first instance of pat

after

start(x).

\italic{match}(x, pat) - match pat only if it begins at start(x).

\italic{anyof}(x, set) - find the first (single) character after start(x)

that is one of the characters in the set.

\italic{span}(x, set) - match start(x) and all contiguous subsequent

characters which are in the set.

\italic{token}(x, set) - find the first substring after start(x) which is

composed of characters from set. \

}

As an exercise in full understanding of the search conventions, here is a

definition of token() written in Ness:

\example{\smaller{\italic{function} \bold{token}(x, set)

\leftindent{\italic{subseq} m := anyof (x, set)

\italic{if} m = "" \italic{then}

\

\leftindent{-- there is no element of set

-- in the search area delimited by x}

\leftindent{\italic{return} m}

\italic{end if

if} x = ""\italic{ then}

\leftindent{-- we have to check from m to the end of base(x)

\italic{return} span(toend(m), set)}

\italic{else }\

\leftindent{-- the token must be between m and the end of x

\italic{return} span(extent(m, x), set)}

}\italic{\leftindent{end if}

end function}}}

\section{4. Concatenation}

Two string values can be concatenated with the tilde operator: \concat{~}

\

\example{\smaller{printline("first" ~ "second")}}

will print "firstsecond"; note that there is no space. We can write

another fibonacci function which generates a string of a fibonacci

length:

\example{\smaller{\italic{function} \bold{fibonacci}(integer n)

\leftindent{\italic{if} n < 2 then return "*"

\italic{end if}

print(textimage(n) ~ " ")

\italic{return} fibonacci(n-2) ~ fibonacci(n-1)}

\italic{end function}

}}

From the call printline(fibonacci(5)), the value printed is

5 3 2 4 2 3 2 ********

Concatenation always generates a new string value.

the definition of the copy() function:

Indeed it is part of

\example{\smaller{\italic{function} \bold{copy}(x)

\leftindent{\italic{return} x ~ "" -- to copy x, concatenate it to the

empty string}

\italic{end function}}}

\section{5. Replacement}

In most applications it is sufficient to process an input string or file

and construct the output by concatenation of the pieces of the input with

other constants as needed. Sometimes, however, for example when

modifying

the text displayed in an editor, it is prefereble to replace a piece of

the

text with some other text. For this purpose Ness offers the

\italic{replace}() function. \

Replace(a, b) modifies the base string of a so the portion that was

delimited by a now contains b. The value returned is a subseq value

referring to the new contents of the portion of a; even though the

contents

are a copy of b, they are not in the same base as b. Thus the statements

\leftindent{\example{\smaller{\italic{subseq} m := copy("abcdef")

replace(next(next(start(m))), "QWE")}}

}

will give to m the value aQWEcdef. Note that the first argument of

replace

cannot be a constant, so copy() was used to make a modifiable copy of

"abcdef".

When a replace of subseq x is made within a base string, base(x),

something

must be done about all other subseqs that refer to portions of base(x).

Those that start before x and end after it will have there contents

modified to include the new replacement characters. Those that start

after

the end of x must be modified so they refer to the same characters as

they

did before. More interesting cases occur for existing subseqs which

overlap x. In general the replacement is made as though the new text is

inserted at the end of x and then the old x contents are deleted. More

precise rules can be derived from the examples in Table 1.

\leftindent{\formatnote{.ne 5.5i}

Replace "\sans{efgh}" in

"\italic{\sans{xyz}}"

\sans{ abcd efgh ijkl}

with

The substring

/

d\italic{xyz}ijkl}

\sans{a / bc / defghijkl}

becomes

\sans{a / bc

The substring

/

\italic{xyz}ijkl}

\sans{a / bcd / efghijkl}

becomes

\sans{a / bcd

The substring

/

\italic{xyz}ijkl}

\sans{a / bcde / fghijkl}

becomes

\sans{a / bcd

< The substring

\sans{a / bcdefgh / ijkl}

bcd\italic{xyz} / ijkl}

becomes

\sans{a /

The substring

\sans{a / bcdefghi / jkl}

bcd\italic{xyz}i / jkl}

becomes

\sans{a /

The substring

/

\italic{xyz}ijkl}

\sans{abcd / efg / hijkl}

becomes

\sans{ abcd /

< The substring

\italic{xyz} / ijkl}

\sans{abcd / efgh / ijkl}

becomes

\sans{abcd /

The substring

\italic{xyz}i / jkl}

\sans{abcd / efghi / jkl}

becomes

\sans{ abcd /

The substring

/

\italic{xyz}ijkl}

\sans{abcde / fg / hijkl}

becomes

\sans{ abcd /

< The substring

\italic{xyz} / ijkl}

\sans{abcde / fgh / ijkl}

becomes

\sans{abcd /

The substring

\italic{xyz}i / jkl}

\sans{abcde / fghi / jkl}

becomes

\sans{abcd /

> The substring

\sans{abcdefgh / / ijkl }

\sans{abcd\italic{xyz} / / ijkl}

becomes

> The substring

\sans{abcdefgh / i / jkl}

\sans{abcd\italic{xyz} / i / jkl}

becomes

Replace empty string between \sans{c} and \sans{d} in

with

"\italic{\sans{xyz}}"

< The substring

\sans{a / bc / def}

becomes

\sans{abcdef}

\sans{a / bc /

\italic{xyz}def}

The substring

bc\italic{xyz}d

/ ef}

\sans{a / bcd / ef}

becomes

\sans{a /

< The substring

\italic{xyz}def}

\sans{abc / / def}

becomes

\sans{abc / /

> The substring

\sans{abc / d / ef}

\sans{abc\italic{xyz}

/ d / ef}

becomes

The substring

\sans{abcd / e / f}

\sans{abc\italic{xyz}d / e

/ f}

becomes

}\indent{\bold{Table 1. The effect of replace() on other subseqs.} The

replace performed for each group of lines is shown above the group. Each

line shows an example of some other subseq on the same base and its value

after the replacement. The base string is letters only; the spaces are

for

readability and the slashes indicate the extent of the subseq values. In

general the replacement is made by inserting the replacement at the

finish

of the replaced value and then deleting the replaced value. The <'s

mark

examples where the other subseq ends at the end of the replaced string

and

the >'s indicates examples where it begins there.

}

\section{6. An Example}

The string processing sub-language is illustrated in the example below.

String values are formally known as \italic{subseq} values because they

do

not actually denote strings, but only refer to, or mark, substrings of

underlying base strings. The subseq variables in the example are

\italic{letters}, \italic{text}, \italic{args}, and \italic{filename}.

Concatentation, with \concat{~}, of subseq values creates a brand new

string value and returns a subseq referring to its entirety. Subseq

assignments assign only the reference and do NOT create a new string that

is a copy of the old. The functions token() and span() are built-in

subseq

functions which begin scanning at the start of their first argument and

look for a string meeting the pattern in the second argument. Span()

scans

its first argument and returns a subseq for the maximal initial substring

consisting of characters in the second argument. (The scan may extend

beyond the end of the first argument.) Token() is similar, but begins by

skipping initial characters of the first argument until finding one from

the second argument.

\begindata{bp,539073112}

Version 2

n 0

\enddata{bp,539073112}

\view{bpv,539073112,15,0,0}

\example{\smaller{-- wc.n

-- Count the words in a text.

--

A word is a contiguous sequence of letters.

-- To use as a main program:

--

nessrun -b $ANDREWDIR/lib/ness/wc.n <filename>

-- the number of words in the file is printed.

--- To call from a Ness function:

--

wc_countwords( <a subseq for the text> )

-- returns an integer value giving the number of words.

\italic{subseq} letters

-- a list of the letters that \

-- may occur in words

:= "abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz"

~ "ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ"

-- countwords(text) counts the number of sequences \

--

of adjacent letters

--- 'text' is a subseq for a substring of the full text

--

token(x, m) searches forward from the beginning of

--

x through the rest of text for the first sequence \

--

of characters all of which are in m

---

Any Ness program can call wc_countwords().

-\leftindent{\italic{integer}}

\italic{function} \bold{wc_countwords}(text)

\leftindent{\italic{integer} count

\italic{subseq} t

count := 0

-- no

t := token(text,letters)

words so far

-- find first word

\leftindent{\leftindent{\leftindent{\leftindent{-- check to see if the

token found

-- starts after the end of the text}}}}

\italic{while} t /= "" \italic{and} extent(t, text) /= "" \italic{do}

\leftindent{

count := count + 1

-- count this word

t :=

-- find next word

-- start search at next(t), \

-- the first character after \

-- the preceding word

token(finish(t), letters)

-- if no word was found, token()

-- returns an empty string}

\italic{end} \italic{while}

\italic{return} count}

\italic{end} \italic{function} \

\begindata{bp,539076424}

Version 2

n 0

\enddata{bp,539076424}

\view{bpv,539076424,16,0,0}

-- the main program initializes the global variable,

--

reads a file, counts the number of words in it,

--

and prints a line

-- span(x, m) finds the longest initial substring of

--

x composed of characters from m

-- ~ indicates concatenation of string values

-\italic{function} \bold{main}(args)\leftindent{

\italic{subseq} filename

-- extract the file name from argument list

-- find the initial substring of args which is \

-- composed of letters, digits, dots, and slashes.

filename := span(start(args), letters ~ "./0123456789")

-- read file, count words, and print result

printline ("The text of " ~ filename ~ " has "\leftindent{

~ textimage(wc_countwords(readfile(filename))) \

~ " words")}}

\italic{end} \italic{function}

-- Select some text.

Type ESC ESC, and respond to \

-- the "Ness:" prompt with

--

wc_showcount()

--- The following function will be called and will show \

-- the number of words in the current selection

-\italic{function} \bold{wc_showcount}() \leftindent{\

TellUser(textimage(wc_countwords(\leftindent{\leftindent{

currentselection(currentinset))))}}}

\italic{end} \italic{function}

-- To use the following entry point, \

-- put these lines in your .atkinit:

--

load ness

--

call ness-load $ANDREWDIR/lib/ness/wc.n

-- Then choosing the menu entry "Count words" will show \

-- a count of the words in the current selection

-\italic{extend} "\bold{view:textview}"\leftindent{

\italic{on} \italic{menu} "Search/Spell,Count words~60"\leftindent{

wc_showcount()}

\italic{end} \italic{menu}}

\italic{end} \italic{extend}}}

\begindata{bp,539080024}

Version 2

n 0

\enddata{bp,539080024}

\view{bpv,539080024,17,0,0}

Execution of this function for two examples went like this:

\leftindent{

% \bold{nessrun wc.n wc.n}

Compile okay.

Elapsed time is 2903 msec.

The text of wc.n has 407 words

Execution okay.

Elapsed time is 1532 msec.

% \bold{nessrun wc.n ness.c}

Compile okay.

Elapsed time is 1522 msec.

The text of ness.c has 4617 words

Execution okay.

Elapsed time is 12284 msec.}

\bold{Appendix:

$ANDREWDIR/lib/ness/demos}

These demonstration files each contain an explanation of how to use them.

In general, they should be copied to /tmp before editing them with ez;

they must be read-write in order to display their effects. (And if they

are editted directly in $ANDREWDIR/lib/ness/demos, they leave .CKP files

around charged against your account.)

\leftindent{\description{happybday.d - Click on the cake for birthday

greetings.

birth.db - A data base.

sorting.

capstest.d

-

Click on a reference in a CF field.

Try

Two different approaches to scanning text.

bank.d - A prototypical "parametric letter".

calc.d - Yet another calculator.

The most truly programmable yet.

volume.d - Very simple illustration of something the NextStep

application

builder can't do.

}}

questionnaire.msg - How to send a questionnaire and have automatic

reply.

\enddata{text,538986648}