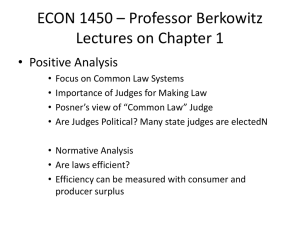

Econ 522 – Lecture 4 (Sept 18 2007)

advertisement

Econ 522 – Lecture 4 (Sept 18 2007) Midterm will be on Tuesday, October 30 (day before Thanksgiving) Today: Property Law Why do we need property law at all? In a sense, this is simply a question of why we prefer a “civil society” of any sort to anarchy. Suppose there are two neighboring farmers, who can do one of two things: farm their own land a lot, or farm a little and steal crops from their neighbor a lot. Stealing may be less efficient than planting my own crops – I have to carry the crops from your land to mine, I may drop some along the way; I have to steal at night, so you won’t see me, so I have to move slower. But if I steal your crops, I don’t have to put in all the effort of planting and watering – I let you do the work and I steal at the end, just before you harvest. Consider the game with no legal protections for private property: Farmer 1 Farm Steal Farmer 2 Farm 10, 10 15, -5 Steal -5, 15 0,0 Just like the prisoner’s dilemma – both farmers stealing from each other instead of growing more crops is the only equilibrium, even though that outcome is Paretodominated. Suppose there were lots of farmers facing this same problem, and they came up with the following solution. Institute some notion of property rights, and some sort of government that could punish people who steal others’ crops. Obviously, setting up this system would cost something. Now the game becomes Farmer 1 Farm Steal Farmer 2 Farm 10-c, 10-c 15-P, -5-c Steal -5-c,15-P -P,-P If the punishment is sufficiently large, and the cost to each farmer is sufficiently small, this would establish (Farm,Farm) as an equilibrium, leading to much better results than before. The main idea here is that anarchy is inefficient – I spend time and effort stealing from you, or defending my own property from thieves, instead of doing productive work. Establishing property rights, and legal recourse for when they are violated, is one way to get around this problem. One early, “classic” court ruling on property law: Pierson v. Post Decided in 1805 by the New York Supreme Court Post had organized a fox hunt, and was in pursuit of a fox Pierson appeared “out of nowhere,” killed the fox, and took off with it Post sued to get the fox back, saying that since he was chasing it, he owned it Lower court sided with Post; Pierson appealed the decision to the NY Sup Ct (Post and Pierson were apparently both wealthy, and pursued the case on principal or out of spite – both spent far more than the value of the fox in pursuing the claim) The fundamental question: when do you own an animal? I mention it here not because we care that much about when you establish possession of a wild animal, but because the court – both the majority and the dissenting opinion – were explicit about considering the economic effects their ruling would lead to Court ruled for Pierson – among other things, they say that: “If the first seeing, starting or pursuing such animals . . . . should afford the basis of actions against others for intercepting and killing them, it would prove a fertile source of quarrels and litigation.” That is, if the first to chase an animal owned it, there would be endless disputes and court cases; and so they favored a more “bright line” rule of ownership which would lead to fewer disagreements (They also point out that just because an action is “uncourteous or unkind” does not make it illegal) Dissenting opinion, however: a fox is a “wild and noxious beast,” and killing them is “meritorious and of public benefit” – Post should own the fox, in order to create incentive for fox hunting So, tradeoff: Fast fish/loose fish Pierson gets the fox Simpler rule Easier to implement Fewer disagreement Iron-holds-the-whale Post gets the fox More efficient incentives (stronger incentive to pursue animals that may be harder to catch) Cooter and Ulen define property as “a bundle of legal rights over resources that the owner is free to exercise and whose exercise is protected from interference by others.” Of course, property rights aren’t absolute. In the appendix to chapter 4, they give examples of different conceptions of property rights. Without getting into the philosophy behind a property rights system, it’s clear that a conception of property rights must answer four fundamental questions: What things can be privately owned? Clearly not everything – nobody owns the ocean, can’t own another person, etc. Cultural artifacts. Ancient Jewish law – ownership over sold land was not permanent, it reverted to its ancestral owner after 50 years. What can (and can’t) an owner do with his property? Again, not everything – can’t use your own property in a way that creates a nuisance to others. Many of the examples when we discuss Coase will have to do with limiting what a person can do with his property. I own my kidneys, but I can’t sell one. If I own a building that has historical significance, I can’t necessarily destroy it or change it in certain ways. How are property rights established? In the whaling example, or the fox hunt example – what does it take to establish ownership? And on the flip side, when can property rights be revoked? Eminent domain – the government’s right to seize private property. In many cases when government wanted to encourage migration into new areas, free land, conditional on you farming it or developing it. Negligent landlords. What remedies are given when property rights are violated? Rights (my rights to use my property in certain ways) and prohibitions (other people can’t interfere) have no meaning unless they are enforced. So how do I get compensated if my property rights are violated? Obviously, one of the fundamental things you can do with private property is to trade or sell it to someone else. Since we’re largely interested with efficiency – in part, whether property ends up in the hands of whoever values it the most – we’ll first talk a bit about… Bargaining Theory We’ll start with the example in Cooter and Ulen. Suppose I have a car, and “the pleasure of owning and driving the car” is worth $3000 to me. You have $5000, you like my car, and you decide the pleasure of owning and driving my car would be worth $4000 to you. Clearly, me holding onto the car is not Pareto-efficient. There are lots of Paretoimprovements possible: each of them involves me giving you the car, and you giving me some amount of money, such that we’re both better off than before. $3000 is my “threat point” – it’s the level of utility that I can guarantee myself by not trading with you, and so there’s no reason for me to accept an outcome where I end up with less than $3000 worth of utility. This is also referred to as my “reservation utility”, or as my “outside option”, since it’s what I can get by refusing to cooperate. $5000 is your threat point – you already have $5000, so there’s no reason for you to settle for an outcome worth less than that to you. Since the car is worth more to you than to me, there are potential gains from trade. Transferring the car from me to you creates $1000 of additional surplus. So a bargaining outcome can be thought of as a decision of how to divide up this additional surplus. There are lots of different approaches to modeling bargaining – some are based on certain axioms or assumptions, some use game theory – but in this case, they all predict that I’ll sell you the car for some price between $3000 and $4000. Many of them specifically predict that you’ll pay $3500 for the car – that is, that we’ll divide the $1000 of surplus created by the sale evenly, so we each end up $500 better off than before. However, there are a couple of key assumptions here that allow us to predict a nice, efficient outcome. Next lecture, we’ll consider situations in which bargaining like this cannot always be counted on to lead to efficiency. But in the cleanest cases – a small number of parties, and no problems of private information – bargaining theory will generally lead to efficiency. If I have a car that’s worth more to you than it is to me, we will both find it worthwhile to come to some agreement where you get the car and we both find ourselves better off. And this brings us to Coase. Two weeks ago, we recapped General Equilibrium Theory, including the First Welfare Theorem, which was that under the right conditions, free markets lead to Pareto-efficient outcomes. However, we pointed out that this result breaks down when there are externalities. One way to see Coase is a way to salvage this free-markets-lead-to-efficiency result, even with externalities, by allowing private bargaining, or creating additional markets, to fix the externalities. One way to interpret Coase is that we can overcome externalities by expanding property rights to include the good that was previously causing an externality. Ronald Coase (1960), “The Problem of Social Cost.” We’ll begin with Coase’s example. Suppose that on adjacent tracts of land, there is a farmer and a cattle rancher. The rancher’s cattle will occasionally stray onto the farmer’s land and eat some of the crops. And the bigger the cattleman’s herd, the more damage will be done to the farmer’s crops. First, consider what happens when the farmer has no recourse, that is, when the rancher is not liable for damage done by his herd. When the rancher is deciding on the size of his herd, he weighs only the private costs and benefits, ignoring the incremental damage that a larger herd would do to his neighbor’s crops. So on the margin, this may lead him to a cattle herd that’s inefficiently large. In addition, since he isn’t harmed by the damage done by his herd, he has no incentive to build a fence or to do anything else to rein in his herd, Next, consider what happens when the rancher is liable for any damage done by his herd. Now, when he decides how big a herd to raise, he will consider the incremental damage done to his neighbor, since he has to pay for the damage; and he will consider actions that he can take to restrain his herd, if they are cheaper than paying for the damage. But now there is no incentive for the farmer himself to take any steps to reduce the damage: building a fence, planting less, or planting less along the boundary between the two tracts of land, or planting crops that cows don’t like along the boundary, or any other steps that might also be cheaper than the damage done. Suppose that it’s cheaper for the farmer to fence in his crops, than for the rancher to fence in his herd. When the rancher is not liable for damage done by his herd, this is what will happen. But when the rancher is liable, the farmer will have no reason to build the fence; so the rancher might build his fence, which is more expensive. So one allocation of legal liability seems to be more efficient. But here are the two main points of Coase. First of all, that the problem is not just that the rancher is doing harm to the farmer; since if the rancher is made liable for the damage, or forced to restrain his herd, then it is instead the farmer who in a sense is doing harm to the rancher. He refers to this as the “reciprocal” nature of the problem. Thus, he rephrases the question in terms of efficiency instead of blame. That is, he doesn’t ask, should the rancher be allowed to harm the farmer or not? Instead, he asks, given that either the rancher’s activities will harm the farmer, or the farmer’s presence, by restraining the rancher, will harm the rancher; so we should figure out which harm is greater. And the second, more important point of Coase is that, in his words, as long as the pricing system works smoothly, that is, as long as there are not great costs and impediments that prevent the rancher and farmer from bargaining with each other and striking mutually beneficial deals, then they will negotiate themselves back into an efficient situation. If it’s cheaper for the farmer to fence in his land rather than the rancher to fence in his herd, then the rancher will pay the farmer to do this, rather than incur the costs of the losses or build his own fence; or, if the rancher is not liable, the farmer will choose do this on his own. If it’s cheaper for the rancher to reduce the size of his herd, he’ll do this on his own (because he’s liable), or because the farmer pays him to. So as long as the rancher and farmer are allowed to bargain and come to mutually beneficial agreements, they will lead themselves to the efficient outcome. (You can think of this as “creating a market for crop damage.”) Coase gives a number of other examples of situations with externalities, mostly in the area of nuisance law, and repeats the point that, regardless of who is initially held responsible for the harm, negotiation and trade will lead to efficiency from any starting point. Some of his other examples: An early English case of a building which was built in such a way that it blocked air currents from turning a windmill A building in Florida which cast a shadow over the swimming pool and sunbathing areas of a nearby hotel A doctor whose office was next door to a confectioner, who built a new examination room and found that the vibration from the confectionery’s machinery prevented him from listening to his patients’ chests through a stethoscope in that room A chemical manufacturer whose fumes interacted with a weaver’s products while they were drying after bleaching A house whose chimney no longer worked well after its neighbors rebuilt their house to be taller In each example, he argues that, regardless of who is held to be liable, the parties can negotiate with each other and take whatever remedy is cheapest to fix (or endure) the situation. To quote Coase: “Judges have to decide on legal liability but this should not confuse economists about the nature of the economic problem involved. In the case of the cattle and the crops, it is true that there would be no crop damage without the cattle. It is equally true that there would be no crop damage without the crops. The doctor’s work would not have been disturbed if the confectioner had not worked his machinery; but the machinery would have disturbed no one if the doctor had not set up his consulting room in that particular place… If we are to discuss the problem in terms of causation, both parties cause the damage. If we are to attain an optimum allocation of resources, it is therefore desireable that both parties should take the harmful effect into account when deciding on their course of action. It is one of the beauties of a smoothly operating pricing system that… the fall in the value of production due to the harmful effect would be a cost for both parties.” To try to make this more clear, let’s go back to our example from two weeks ago, of a simple economy with beer and hops. Suppose now that there are two consumers – one who grows hops and drinks beer, the other one owns the factory that turns hops into beer. But now suppose that in addition to turning hops into beer, the factory also outputs smoke, which pollutes the air, and that the first consumer also values clean air. So let’s suppose he is again endowed with 1000 pounds of hops, has a utility function of 100 log b + h + 3 a Where b is the beer he drinks, h is the hops he eats, and a is the quality of the air he gets to breathe, on a scale of 0 to 100. Suppose that the technology for making x gallons of beer requires x^2/8 pounds of hops, and reduces the air quality from 100 to 100 – x. Suppose the second consumer, who owns the factory, has no endowments of any goods, and only likes hops. First, suppose that there are no restrictions on pollution. The equilibrium prices we found before are still the only equilibrium. So hops costs $1 per pound and beer costs $5 per gallon. The first consumer demands 20 gallons of beer, and sells 100 pounds of hops to buy it; 50 of that is used in the production of beer, and the other 50 is consumed by the second consumer (who buys it with the $50 of profits the factory earns). Air quality is 100 – 20 = 80, the first consumer’s utility is 100 log 20 + 900 + 3 (80) = 1440, and the second consumer’s utility is 50. But here’s the interesting part. Because of the externality, this outcome is not Paretoefficient. There are lots of possible Pareto-improvements, all of them involving lower production. Here’s one: The first consumer goes to the factory and says, “Instead of buying 20 gallons of beer at $5 a gallon, how about you only make 16 gallons of beer, but I’ll buy them at $5.25 a gallon?” 16 gallons only requires 32 pounds of hops to make; the firm’s profits are 16 * 5.25 – 32 = $52, so the consumer who owns the factory gets utility of 52 instead of 50. The first consumer sells 84 pounds of hops to buy the beer, and ends up with utility of 100 log 16 + 916 + 3 (100 – 16) = 1445. So everyone is better off. This new outcome is not an equilibrium outcome, though, because at a price of $5.25 a gallon, the firm would want to produce more beer, so at these prices, the market for beer won’t clear. But now suppose we were to introduce a market for clean air. First, suppose that the first consumer is endowed with all the clean air, and that the factory has to “buy” from him each unit of air that they want to pollute. The new equilibrium prices turn out to be $6.72 per gallon of beer, $1 per pound of hops, and $3 per unit of air. Around 15 gallons of beer are produced, so the air quality is about 85. The first consumer sells 15 units of clean air to the factory, drinks 15 gallons of beer, and ends up with utility of 1470, higher than before. The firm’s profits are now around 28, since they have to pay for the air they pollute. So the second consumer’s payoff is lower. But the sum of the two consumers’ utilities are higher than before. OK, but now suppose that instead of the consumer starting with all the air rights, the factory starts off with 20 units of air rights – it can buy more to pollute more than that, or the consumer can buy some to get the factory to pollute less. In this example, equilibrium prices are exactly the same as before - $3 for air, $6.72 for beer, $1 for hops. The same 15 gallons of beer are produced in equilibrium. The consumer now buys back 5 units of air rights from the factory, drinks 15 gallons of beer, and sells more hops than before to afford it. His utility is lower than when he started with all the air rights, but the result is still Pareto-efficient. That’s the main result of Coase: as long as there are no costs associated with market transactions, if every good in the economy is priced and traded, the result will be Paretoefficient. Who starts with what – how initial property rights are allocated – will affect distribution, but will not affect efficiency. (In some cases, like this one, the initial allocation of air rights doesn’t change production at all. In other cases, where there are wealth effects, it will – different allocations of initial rights make different players more or less wealthy, which may lead them to different choices – but in any beginning allocation, the equilibrium outcome will be Pareto-efficient.) Again, the point here is that, even when there are externalities, whenever there are no impediments to bargaining, negotiations should lead back to the efficient outcome, regardless of how initial rights are allocated; and that one way to facilitate such negotiations are to extend property rights to cover the good that was not being allocated efficiently. Harold Demsetz, in “Toward a Theory of Property Rights” (on the syllabus), summarizes Coase as saying that in a world without transaction costs, “The output mix that results when the exchange of property rights is allowed is efficient and the mix is independent of who is assigned ownership (except that different wealth distributions may result in different demands).” Elsewhere, he points out, “A primary function of property rights is that of guiding incentives to achieve a greater internalization of externalities.” In order for an externality to persist, he argues, “The cost of a transaction in the rights between the parties… must exceed the gains from internalization.” (He points out that effective transaction costs can be high for either natural reasons or legal reasons – the transaction cost if I wanted to sell a kidney might be high because of the risk of being caught and punished, plus the difficulty in finding a willing buyer given the legal concerns.) Demsetz then makes the case that will naturally evolve to be more complete as this becomes economically more important – that is, as the value of overcoming a particular externality grows relative to the costs of implementing more expansive (and more complex) property rights. In his words, “Property rights develop to internalize externalities when the gains of internalization become larger than the cost of internalization.” He gives the example of land ownership among Native Americans. Specifically, he points out that a close relationship exists between the development of private land rights and the development of the commercial fur trade. When land is not privately owned, nobody has an incentive to increase or maintain the stock of animals on the land, or to limit their hunting; so overhunting will tend to occur. Before the fur trade became established in North America, hunting was done primarily for food; the externality that hunting imposed on other hunters, by lowering the amount of game available, was present, but was a fairly small problem. And historians have established that at that time, Native Americans did not have anything resembling private ownership of land. As the fur trade began, furs became more valuable, since they could be traded for other goods that were not plentiful; and so the scale of hunting increased. This, in turn, increased the importance of overhunting and the size of the externality that hunters imposed on each other. And at the same time, in the areas where the fur trade was most important, Native Americans began to recognize exclusive family rights to hunt and trap in particular areas. (Neat quote: “a starving Indian could kill and eat another’s beaver if he left the fur and the tail.”) He points out that at the same time, in the southwestern plains, where there were no animals of the same commercial significance, and where the animals that were there tended to roam over a larger area, similar private property rights did not emerge. In addition, in the areas where private rights to land were emerging, careful steps were taken to avoid overhunting – such as rotating among different hunting areas year by year, and maintaining one area in which no hunting was done. Coase’s conclusion, of course, is predicated on the absence of transaction costs, that is, in our example, that there is little or no cost to trading the pollution rights in the example. Coase is clear that when there are no transaction costs, the initial allocation of property/rights does not matter for efficiency (although it does matter for distribution); but that when there are transaction costs, the initial allocation does matter. Similarly, Demsetz assumes that there are some costs to implementing more complete property rights, and that property rights expand as the externalities they overcome increase in value to eclipse these costs.