Econ 522 Economics of Law Dan Quint Spring 2014

advertisement

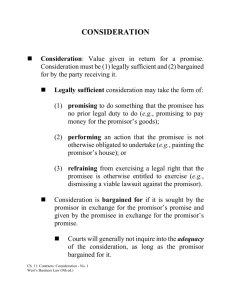

Econ 522 Economics of Law Dan Quint Spring 2014 Lecture 10 Logistics Second homework due Thursday First midterm next Monday (March 3) covers through the end of property law (today’s lecture) practice problems on website, along with answers to one 1 Discussion question Should record labels sue music downloaders? 2 We’ll wrap up property law with two ways the government limits property rights Government can tell you how you can or can’t use your property Regulation The government can take your property “Eminent domain” 3 Eminent Domain 4 Takings One role of government: provide public goods When public goods are privately provided undersupply Defense, roads and infrastructure, public parks, art, science… To do this, government needs land (which might already belong to someone else) In most countries, government has right of eminent domain Right to seize private property when the owner doesn’t want to sell This type of seizure also called a taking 5 Takings U.S. Constitution, Fifth Amendment: “…nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.” Government can only seize private property for public use And only with just compensation Consistently interpreted to mean fair market value – what the owner would likely have been able to sell the property for 6 Takings Why allow takings? 7 Takings Why allow takings? Why these limitations? why require compensation? 8 Takings Why allow takings? Why these limitations? why require compensation? $10 MM $9 MM $3 MM $1 MM 9 Takings Why allow takings? Why these limitations? why require compensation? why only for public use? 10 Takings Why allow takings? Why these limitations? why require compensation? why only for public use? The government should only take private property (with compensation) to provide a public good when transaction costs preclude purchasing the necessary property through voluntary negotiations 11 Poletown Neighborhood Council v Detroit 1981: GM was threatening to close Detroit plant Would cost city 6,000 jobs, millions in tax revenue City used eminent domain to condemn entire neighborhood 1,000 homeowners and 100 businesses forced to sell land then used for upgraded plant for GM city claimed employment and tax revenues were public goods, which justified use of eminent domain Mich Sup Ct: “Alleviating unemployment and revitalizing the economic base of the community” valid public purposes; “the benefit to a private interest is merely incidental” Overturned in 2004 ruling (Wayne v Hathcock) 12 More recent case: Kelo v. City of New London (2005 US Supreme Court) Posner (Economic Analysis of Law) describes: …Pfizer had decided to build a large research facility next to a 90acre stretch of downtown and waterfront property in New London. The city hoped that Pfizer’s presence would attract other businesses to the neighborhood. The plaintiffs owned residential properties located on portions of the 90-acre tract… It might have been impossible to develop those areas… had the areas remained spotted with houses. The city… solved the problem by condemning the houses. It said, “the area was sufficiently distressed to justify a program of economic rejuvenation.” Attorney arguing case: “If jobs and taxes can be a justification for taking someone’s home or business, then no property in America is safe.” 13 Recent example of eminent domain Bruce Ratner owned the Nets from 2004-2011 Bought for $300 MM, sold for less (80% for $200 MM) This “loss” held up by David Stern as evidence NBA owners were losing money, players needed to make concessions Recent Malcolm Gladwell article on Grantland Ratner didn’t want the Nets – he wanted development rights to a 22-acre site in Brooklyn Buying it all up would be difficult Seizure a la Kelo would be possible, but politically unpopular If plans included a basketball stadium, becomes clear-cut case for eminent domain Even if Ratner took a “loss” on the team, he got what he wanted out of the deal 14 Regulation 15 Multiple forms of public ownership Open Access Anyone free to use the resource Leads to overutilization (Tragedy of the Commons) Example: oyster beds Unanimous Consent Opposite of open access – multiple owners must all agree to any use of the resource Leads to underutilization Example: empty storefronts in post-Communist Moscow “Anti-commons” caused by existing intellectual property Political Control/Regulation 16 Third form of public ownership: political control/regulation Dividing the mountain pasture among individual owners would require fencing it, which is prohibitively expensive. Instead, the highland pasture is held in common, with each village owning different pastures that are separated by natural features such as lakes and mountain peaks. If each person in the village could place as many sheep as he or she wanted in the common pasture, the meadows might be destroyed and eroded by overuse. 17 Third form of public ownership: political control/regulation In fact, the common pastures in the mountains of Iceland have not been overused and destroyed, because the villages have effective systems of governance. They have adopted rules to protect and preserve the common pasture. The sheep are grazed in common pasture in the mountains during the summer and then returned to individual farms in the valleys during the winter. The total number of sheep allowed in the mountain pasture during the summer is adjusted to its carrying capacity. Each member of the village receives a share of the total in proportion to the amount of farmland where he or she raises hay to feed the sheep in the winter. 18 Similar to how Iceland maintains fishing stock Open access would lead to overfishing, deplete fishing stock Government of Iceland decides how much fish should be caught in total each year People own permits which are right to catch a fixed fraction of each year’s total Permits are property – can be bought, sold, etc. 19 Regulation 20 Regulation: Pennsylvania Coal v. Mahon 1800s: PA Coal purchased mineral and support estates, Mahon owned surface 1921: Kohler Act prohibited “mining of surface estate anthracite coal in such a way as to cause the subsidence of, among other things, support estate any structure used as a human habitation.” mineral estate PA Coal sued government, claiming the regulation was same as seizing their land (without compensation) “…While property may be regulated to a certain extent, if regulation goes too far it will be recognized as a taking.” 21 Regulation: Pennsylvania Coal v. Mahon 1800s: PA Coal purchased mineral and support estates, Mahon owned surface 1921: Kohler Act prohibited “mining of surface estate anthracite coal in such a way as to cause the subsidence of, among other things, support estate any structure used as a human habitation.” mineral estate PA Coal sued government, claiming the regulation was same as seizing their land (without compensation) “…While property may be regulated to a certain extent, if regulation goes too far it will be recognized as a taking.” 22 Regulation: Pennsylvania Coal v. Mahon 1800s: PA Coal purchased mineral and support estates, Mahon owned surface 1921: Kohler Act prohibited “mining of surface estate anthracite coal in such a way as to cause the subsidence of, among other things, support estate any structure used as a human habitation.” mineral estate PA Coal sued government, claiming the regulation was same as seizing their land (without compensation) “…While property may be regulated to a certain extent, if regulation goes too far it will be recognized as a taking.” 23 Regulation: Pennsylvania Coal v. Mahon 1800s: PA Coal purchased mineral and support estates, Mahon owned surface 1921: Kohler Act prohibited “mining of surface estate anthracite coal in such a way as to cause the subsidence of, among other things, support estate any structure used as a human habitation.” mineral estate PA Coal sued government, claiming the regulation was same as seizing their land (without compensation) “…While property may be regulated to a certain extent, if regulation goes too far it will be recognized as a taking.” 24 Blume and Rubinfeld, “Compensation for Takings: An Economic Analysis” Support compensation for regulatory takings Shifting burden of regulation from owners of affected property to all taxpayers Equivalent to selling everyone insurance against harmful regulation If such insurance were available, people would buy it But it’s not available, for usual reasons insurance markets may fail adverse selection moral hazard So government should provide it instead… …by paying compensation for regulatory takings 25 Blume and Rubinfeld, “Compensation for Takings: An Economic Analysis” Support compensation for regulatory takings Shifting burden of regulation from owners of affected property to all taxpayers Equivalent to selling everyone insurance against harmful regulation If such insurance were available, people would buy it But it’s not available, for usual reasons insurance markets may fail adverse selection moral hazard So government should provide it instead… …by paying compensation for regulatory takings 26 Zoning Zoning laws Distinguish industrial areas from residential areas 27 Zoning Zoning laws Distinguish industrial areas from residential areas Nollan v California Coastal Commission (US Sup Ct, 1987) Nollans owned coastal property Asked for permit to expand building, which would diminish view Commission: donate a public walking path, and you get permit Supreme Court: such a deal only legal if there is clear connection – a nexus – between the harm being done and the remedy 28 Zoning Zoning laws Distinguish industrial areas from residential areas Nollan v California Coastal Commission (US Sup Ct, 1987) Nollans owned coastal property Asked for permit to expand building, which would diminish view Commission: donate a public walking path, and you get permit Supreme Court: such a deal only legal if there is clear connection – a nexus – between the harm being done and the remedy 29 Property law: the big-picture question What are benefits and costs of… having property rights at all? expanding property rights to cover more things? introducing an exception/limitation to property rights? When will benefits outweigh the costs? End of material on first midterm Up next: contract law 30 Contract Law 31 Looking back The question we’ve posed: Suppose we set up the rules, and then everyone does what’s best for them under those rules. What rules do we set up, if we want efficient outcomes? A couple of the ideas we’ve seen so far Coase: initial rules don’t matter if no transaction costs “More complicated” rules (such as more extensive property rights) lead to more efficient use of a resource, but also higher costs Injunctive relief when transaction costs low, damages when high 32 So far, we haven’t worried about the details of trade When two parties want to reallocate rights… I want to buy your used car Or you want to “buy” my permission to have a noisy party Or neighbors want to pay a factory to pollute less …we’ve assumed they can do so… …subject (possibly) to there being some transaction costs 33 Timing of transactions Some transactions happen all at once I hand you a check for $3500, you hand me the keys to your car There might be search costs and bargaining costs… …but no enforcement costs But some don’t Neighbors pay the factory to pollute less going forward Need to make sure factory sticks to the agreement What if technology changes and factory wants to start polluting more again? 34 Lots of transactions are like this I’m flying to Florida for Spring Break I hire someone to paint my house… …or fix my car I ask you not to have a party on a particular night We’re doing an in-class experiment, you want to buy a poker chip from someone but don’t have any cash 35 This is what contracts are for A contract is a promise… …which is legally binding Point of contracts: to enable trade when transactions aren’t concluded immediately 36 Example: the agency (trust) game Player 1 (you) Don’t Trust me Player 2 (me) (100, 0) Share profits (150, 50) Keep all the money (0, 200) Subgame perfect equilibrium: I’ll keep all the money; so you don’t trust me Inefficient outcome (100 < 200) And we’re both worse off 37 (One solution: reputation) 38 Another solution: legally binding promises Player 1 (you) Don’t Trust me Player 2 (me) (100, 0) Share profits (150, 50) Keep all the money (125, 25) Now we get cooperation (and efficiency) Purpose of contract law: to allow trade in situations where this requires credible promises 39 Contract: a legally binding promise Point of contracts: to enable trade when transactions aren’t concluded immediately Obvious question: which promises should be legally binding, and which should not? 40 What types of promises should be enforced by the law? “The rich uncle of a struggling college student learns at the graduation party that his nephew graduated with honors. Swept away by good feeling, the uncle promises the nephew a trip around the world. Later the uncle reneges on his promise. The student sues his uncle, asking the court to compel the uncle to pay for a trip around the world.” “One neighbor offers to sell a used car to another for $1000. The buyer gives the money to the seller, and the seller gives the car keys to the buyer. To her great surprise, the buyer discovers that the keys fit the rusting Chevrolet in the back yard, not the shiny Cadillac in the driveway. The seller is equally surprised to learn that the buyer expected the Cadillac. The buyer asks the court to order the seller to turn over the Cadillac.” “A farmer, in response to a magazine ad for “a sure means to kill grasshoppers,” mails $25 and receives in the mail two wooden blocks with the instructions, “Place grasshopper on Block A and smash with Block B.” The buyer asks the court to require the seller to return the $25 and pay $500 in punitive damages.” 41 The Bargain Theory of Contracts 42 The bargain theory of contracts Developed in the late 1800s/early 1900s A promise should be enforced if it was given as part of a bargain, otherwise it should not Bargains were taken to have three elements Offer Acceptance Consideration 43 What is consideration? Promisor: person who gives a promise Promisee: person who receives it In a bargain, both sides must give up something reciprocal inducement Consideration is what the promisee gives to the promisor, in exchange for the promise Under the bargain theory, a contract becomes enforceable once consideration is given 44 What is consideration? Promisor: person who gives a promise Promisee: person who receives it In a bargain, both sides must give up something reciprocal inducement Consideration is what the promisee gives to the promisor, in exchange for the promise Under the bargain theory, a contract becomes enforceable once consideration is given 45 The bargain theory does not distinguish between fair and unfair bargains Hamer v Sidway (NY Appeals Ct, 1891) Uncle offered nephew $5,000 to give up drinking and smoking until his 21st birthday, then refused to pay “The promisee [previously] used tobacco, occasionally drank liquor, and he had a legal right to do so. That right he abandoned for a period of years upon the strength of the promise… We need not speculate on the effort which may have been required to give up the use of these stimulants. It is sufficient that he restricted his lawful freedom of action within certain prescribed limits upon the faith of his uncle’s agreement, and now, having fully performed the conditions imposed, it is of no moment whether such performance actually proved a benefit to the promisor, and the court will not inquire into it.” 46 Under the bargain theory, what is the remedy? Expectation damages the amount of benefit the promisee could reasonably expect from performance of the promise meant to make the promisee as well of as he would have been, if the promise had been fulfilled 47 Problems with the bargain theory Not that accurate a description of what modern courts actually do Not always efficient Does not enforce certain promises that both promisor and promisee might have wanted to be enforceable 48 Problems with the bargain theory Not that accurate a description of what modern courts actually do Not always efficient Does not enforce certain promises that both promisor and promisee might have wanted to be enforceable Does enforce certain promises that maybe should not be enforced 49 For efficiency, what promises should be enforced? 50 What promises should be enforced? In general, efficiency requires enforcing a promise if both the promisor and the promisee wanted it to be enforceable when it was made different from wanting it to actually be enforced 51 What promises should be enforced? In general, efficiency requires enforcing a promise if both the promisor and the promisee wanted it to be enforceable when it was made different from wanting it to actually be enforced The first purpose of contract law is to enable people to cooperate by converting games with noncooperative solutions into games with cooperative solutions or, enable people to convert games with inefficient equilibria into games with efficient equilibria 52 What promises should be enforced? In general, efficiency requires enforcing a promise if both the promisor and the promisee wanted it to be enforceable when it was made different from wanting it to actually be enforced The first purpose of contract law is to enable people to cooperate by converting games with noncooperative solutions into games with cooperative solutions or, enable people to convert games with inefficient equilibria into games with efficient equilibria 53 So now we know… What promises should be enforceable? For efficiency: enforce those which both promisor and promisee wanted to be enforceable when they were made One purpose of contract law Enable cooperation by changing a game to have a cooperative solution Contract law can serve a number of other purposes as well 54 Information Private/asymmetric information can hinder trade Car example (George Akerloff, “The Market for Lemons”) 55 Information Private/asymmetric information can hinder trade Car example (George Akerloff, “The Market for Lemons”) 56 Information Private/asymmetric information can hinder trade Car example (George Akerloff, “The Market for Lemons”) Contract law could help You could offer me a legally binding warranty Or, contract law could impose on you an obligation to tell me what you know about the condition of the car Forcing you to share information is efficient, since it makes us more likely to trade The second purpose of contract law is to encourage the efficient disclosure of information within the contractual relationship. 57 Next question If a contract is a promise… what should happen when that promise gets broken? could be: I signed a contract with no intention of living up to it but could be: I signed a contract in good faith, intending to keep it… …but circumstances changed, making performance of the contract less desirable, maybe even inefficient! so what should happen to me if I fail to perform? 58