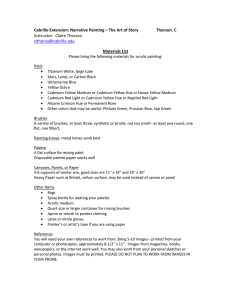

F VI S

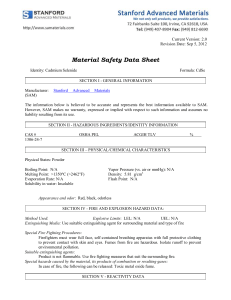

advertisement