RESTRAINING RESTRAINTS: DECREASING THE USE OF RESTRAINTS ON

INDIVIDUALS WITH SPECIAL NEEDS

Heather Arlene Gold

B.S., University of California Davis, Davis 2006

PROJECT

Submitted in partial satisfaction of

the requirements for the degree of

MASTER OF ARTS

in

EDUCATION

(Special Education)

at

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, SACRAMENTO

SPRING

2011

© 2011

Heather Arlene Gold

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

ii

RESTRAINING RESTRAINTS: DECREASING THE USE OF RESTRAINTS ON

INDIVIDUALS WITH SPECIAL NEEDS

A Project

by

Heather Arlene Gold

Approved by:

__________________________________, Committee Chair

Rachael Gonzales, Ed.D.

____________________________

Date

iii

Student: Heather Arlene Gold

I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format

manual, and that this project is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for

the project.

__________________________, Graduate Coordinator

_________________

Bruce Ostertag, Ed.D.

Date

Department of Special Education, Rehabilitation, School Psychology, and Deaf Studies

iv

Abstract

of

RESTRAINING RESTRAINTS: DECREASING THE USE OF RESTRAINTS ON

INDIVIDUALS WITH SPECIAL NEEDS

by

Heather Arlene Gold

The use of restraints on individuals with special needs has been increasing over the past

decade, especially among law enforcement agencies. Even though, improper use of restraints can

lead to severe harm and even death there are no federal guidelines on the proper use of restraints

in school systems. However, there are organizations, such as the Council for Exceptional

Children (CEC), that propose guidelines that agencies can follow. This study describes the

current controversies, policies, and use/abuse of restraints by law enforcement agencies. The aim

of this study is to develop awareness and to train law enforcement agencies on the use of

restraints with individuals with special need. The training provided to a select group of police

officers, focused on understanding the importance of restraining restraints, naming the different

types of restraints, identifying characteristics of different disabilities, learning de-escalation

strategies, and how to employ safe “restraints.”

, Committee Chair

Rachael Gonzales, Ed.D.

______________________

Date

v

DEDICATION

To my family; your support, love and encouragement have been instrumental.

You have pushed me to reach all the goals I have set. You have inspired me by your

drive and motivation. You have never doubted my abilities and for that, I am grateful. To

my friends, for always being there for me and believing in me when I no longer did.

Lastly, to my dad; even though you are not here to see my success, I know you are proud.

I love you all and truly appreciate all you have done. Thank you from the bottom of my

heart.

vi

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

To my professor and advisor, Dr. Gonzales, for working diligently with me

throughout this process and for always encouraging me- my project would not have been

accomplished without you. Thank you to all of the police officers, especially my sister,

for volunteering your time and expertise. Your honesty and opinions contributed greatly

to the success of this study. Lastly, to my students, for motivating me and reminding me

every day to advocate for what is right.

vii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Dedication .......................................................................................................................... vi

Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................... vii

Chapter

1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1

Background of Problem ...................................................................................... 2

Statement of Problem .......................................................................................... 3

Statement of Purpose .......................................................................................... 4

Definitions of Terms ........................................................................................... 4

Assumptions........................................................................................................ 6

Justifications ....................................................................................................... 6

Limitations .......................................................................................................... 7

2. REVIEW OF LITERATURE ......................................................................................... 8

Introduction ......................................................................................................... 8

State Regulations ................................................................................................ 8

Death by Restraint............................................................................................. 12

Model of Best Practices .................................................................................... 15

Grafton Winchester Facility.............................................................................. 15

Luiselli’s Study ................................................................................................. 18

Controversy on the Use of Restraints ............................................................... 19

3. METHODOLOGY ....................................................................................................... 24

Participants ........................................................................................................ 25

Training Design ................................................................................................ 25

Pre-Survey......................................................................................................... 27

Training ............................................................................................................. 28

Part 1: Background Information ....................................................................... 29

Part 2: Identification Training ........................................................................... 30

viii

Part 3: De-escalation Strategies ........................................................................ 31

Part 4: Safe Restraint Research ......................................................................... 32

Part 5: Restraint Training .................................................................................. 32

Layout ............................................................................................................... 33

Post Survey ....................................................................................................... 34

4. CONCLUSION/RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................................... 35

Recommendations ............................................................................................. 37

Apendix A. Police Officer Training Pre-Survey............................................................... 39

Apendix B. Restraining Restraints Training PowerPoint ................................................. 42

Apendix C. Welcome to Holland ...................................................................................... 82

Apendix D. Police Officer Training Post-Survey ............................................................. 83

References ......................................................................................................................... 85

ix

1

Chapter 1

INTRODUCTION

There are too many cases of unexpected deaths and injuries that are the outcome

of untrained, inhumane, and in some cases even legal uses of restraint on children (Ryan,

Robbins, Peterson, Rozalski, & Robbins, 2009). There is little research on the abuse or

death caused by law enforcement and school staff because of the use of restraints on

children, specifically kids with special needs. The need to address the issues is essential

as for, hundreds of kids are subjected to improper and unacceptable use of restraints

(Ryan et al., 2009). In a statement by Rocky Nichols (1999), executive director of the

Disability Rights Center, he references ‘cases where kids have been sat on by gym

teachers, rolled up in gym mats, had their hands duct-taped together, and have even been

placed in little boxes as a form of restraint.

The author of this research has personally experienced on the overuse and/or

“abuse” of restraints used on juveniles. On numerous occasions, the author observed

peace officers relying heavily on restraints, such as handcuffs, to get juveniles with

special needs to obey their and/or he teachers orders. According to the author, peace

officers put forth very little if any effort in using non-restraint methods such as, deescalation or “safe” restraint strategies to try and resolve the issue at hand. In one case, a

9-year-old boy was demanded twice to comply and when he refused the officer forcibly

pulled the student by his arm, from the classroom and restrained him using handcuffs.

Luckily, in this case the student was not killed or injured; however, that is not always the

case.

2

Background of Problem

There is no published data the author could find that specifically shows the

number of police brutalities against kids with special needs, yet in recent years there has

been an overwhelming increase of media attention on police related abuse against this

population of individuals. For example, on April 24, 2009 in Chicago a 16 year old boy

(Guzman) with autism was allegedly struck by an officer who ignored the boys and

family’s plea that he was a “special boy” (Rozas, 2009). The boy was standing on the

sidewalk taking a break from working in his family’s fast-food restaurant, when two

police officers pulled up and started asking him questions. Confused, Guzman walked

away. The officers went after him, promoting the boy to run back into the restaurant,

yelling “I’m a special boy.” Despite, Guzman plea with the cops that he was special and

his parents yelling at the officers that he had “special needs” one of the officers hit

Guzman over the head with their baton, creating a gash that required eight staples.

According to the family, Guzman who has the mental capacity of a 5th grader, mumbled

again and again, “I’m sorry, I’m sorry, I submit, I submit.” At the time of the news report

the Chicago police refused to discuss the incident, but relatives of Guzman alleged

assault and said “[it] was an example of why more officers need to be trained in handling

people with special needs” (Rozas, 2009). This is only one of many cases that have

stormed the media headlines across the country.

The Government Accountability Office (GAO), however, has documented

hundreds of allegations of abuse involving restraint or seclusion in schools (Kutz & US

Government Accountability Office, 2009). Of those allegations, Texas and California had

3

a combined 33,095-reported instances in the 2004 school year. This did not include the

hundreds of cases that went undocumented. In addition, the report detailed 10 specific

cases, four of which ended in death. In one of those cases, a 9-year-old boy with learning

disabilities was confined to a dirty small room over 75 times in a six month period for

whistling, slouching and hand-waving. In another case in Florida, a paraprofessional

gagged and duct-taped five boys to their desks and in Texas a 14-year-old boy died when

a special education teacher lay on top of him because he would not stay seated (Kutz &

US Government Accountability Office, 2009).

Unlike hospitals or residential treatments centers, there is not a federal system that

regulates how restraints should or should not be practiced in schools or by law

enforcement in regards to juveniles with special needs (U.S. Department of Education,

2010). Instead, it is left to the individual states government. There are numerous

behavior management methods, as well as research on effective de-escalation and safe

restraint strategies, which all provided knowledge and tools to help support the successful

fulfillment of safely resolving conflict with special needs individuals. Law enforcement

agencies, however, receive minimal if any training on using these strategies.

Statement of Problem

Law enforcement agencies lack the training needed in order to successfully

interact and resolve challenging situations with individuals with special needs. Peace

officers receive little if any training on how to identify individuals with special needs, deescalation strategies and safe restraints. Although, the numbers of individuals born with

special needs are drastically increasing, the amount of training that peace officers are

4

receiving is not. According to the Child Welfare League of America (2002), eight to ten

deaths occur every year because of improperly performed restraint on children.

Statement of Purpose

The purpose of this project is to develop awareness and to train law enforcement

agencies and their officers on the use of restraints with individuals with special needs.

The training focuses on understanding the importance of restraining restraints, naming

the different types of restraints, identifying characteristics of different disabilities,

learning de-escalation strategies, and how to employ safe “restraints.” In order to

construct a successful universal training program it is essential to learn effective research

based strategies that can be employed by the law enforcement agencies. Most

importantly, this requires a solid understanding of the different types of disabilities, a

detailed explanation of behaviors that are associated with these disabilities, and strategies

that are effective with different individual needs. This training will equip the target

audience with strategies, which will allow them to deal with a variety of challenges and

situations.

Definitions of Terms

Restraint

According to the International Society of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nurses

(1999), restraint is any method of restricting an individual’s freedom of movement,

physical activity, or normal access to his or her body. There are three types of restraint:

mechanical, chemical and physical.

5

Mechanical Restraint

According to Ryan and Peterson (2004) mechanical restraint uses a device or

object, such as: a harness, flexible handcuffs or tape, to restrict an individual’s movement

in order to manage or prevent aggressive behavior.

Chemical Restraint

Chemical restraint involves using medication or sprays to control or restrict and

individual’s freedom of movement. Chemical restraint involves using medication or

sprays to control or restrict and individual’s freedom of movement.

Physical Restraint

Physical restraint is using one or more staff member’s bodies to restrict an

individual’s body movement as a way to establish behavioral control and maintain safety

for the individual and/or his/her peers and staff. Physical restraint is the most commonly

used in schools and according to CEC (2009) guidelines it should be the only type of

restraint performed in a school setting.

Special Needs

Refers to individuals who have been diagnosed with a specific learning disability,

such as auditory, visual and sensory processing, as well as individuals diagnosed with

autism (Shapiro, Church & Lewis, 2002). The Individuals with Disabilities Education

Act of 1997 (Pl 105-17) defines specific learning disability as:

A disorder in one or more of the basic psychological processes involved in

understanding or in using language, spoken or written, which disorder may manifest in

6

imperfect ability to listen, think, speak, read, write, spell, or do mathematical

calculations.

Youth/Juveniles

Youth and juveniles are one in the same. They refer to children 0-12 years of age.

Assumptions

There are a few assumptions in regards to the training that was developed through

this project. First, the training will support peace officers by answering any questions

they have regarding juveniles with special needs. Second, peace officers will actively use

the training as soon as they receive the skills and knowledge, so they can actively support

juveniles with special needs. Lastly, law enforcement agencies will follow up with

frequent trainings to insure all officers are up to date with the most current strategies and

disabilities.

Justifications

With the ongoing increase of deaths caused by restraints in schools, treatment

facilities, and detention centers there is an overwhelming need for further research on

interventions and alternative methods that can be used instead of physical restraints.

The outcome of this project will first handily benefit law enforcement agencies by

providing them with safe and effective strategies while working with kids with special

needs. The training will indirectly benefit educators by providing them an additional

trained source to help in emergencies. In addition, youth with special needs and their

families will benefit because there will be less possibility for injures to the student. With

the increase of individuals with special needs, it is imperative that public service workers

7

are receiving training on identifying individuals with special needs, as well as learning

strategies that are effective in working with these individuals. Learning these techniques

will help decrease the need to use mechanical, chemical and physical restraints thus

decreasing the number of injuries and deaths to individuals with special needs.

Limitations

There are various limitations that exist within this project. Only a small number

of peace officers were given a pre-survey and even a fewer number of officers were

provided the training and post-survey. All but two of the officers were working for one

demographic, small rural area. Lastly, one of the peace officers was a relative of the

author and had prior knowledge of the reason for the training.

8

Chapter 2

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

Introduction

The review of literature focuses on two primary studies that discuss effective

strategies that decrease the use of restraints used on individuals with special needs and

mental illness. This review also includes state restraint policies that have been

implemented in schools. The review shows the controversy associated with the use and

non-use of restraints, as well as, the lack of research on law enforcement use of restraints

on individuals with special needs.

State Regulations

The practice of using restraints on students with disabilities has slowly emerged in

public school systems as the increased number of students with emotional and behavioral

challenges are included in general education. Over the past two decades, schools have

grown concerned on how to respond to student behavior problems, especially those that

are aggressive. Schools have leaned to physical restraint as a tool to use to help control

violence (Ryan & Peterson, 2004). There has been many reported incidences of the

improper use of restraints which has led to death and injures thus sparking a need for

state policies and regulations (Baker, 2009).

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) has documented hundreds of

allegations of abuse involving restraint or seclusion, of those allegations Texas and

California had a combined 33,095 reported instances in the 2004 school year (Kutz & US

Government Accountability Office, 2009). This did not include the hundreds of cases

9

that went undocumented. In addition, the report detailed 10 specific cases, four of which

ended in death. In one of those cases in New York, a 9-year-old boy with learning

disabilities was confined to a dirty small room over 75 times in a six month period for

whistling, slouching and hand-waving. In another case in Florida a paraprofessional

gagged and duct-taped five boys to their desks and in Texas a 14-year-old boy died when

a special education teacher lay on top of him because he would not stay seated. Unlike

hospitals or residential treatments centers, there is not a federal system that regulates how

restraints should or shouldn’t be practiced in schools (Kutz & Government

Accountability Office, 2009). Instead, in 2009 U.S Secretary of Education, Arnie

Duncan, wrote a letter encouraging Chief State School Officers to require schools in to

put in places polices (Duncan, 2009).

In their review of state policies concerning the use of physical restraint procedures

in schools, Ryan et al. (2009) found that thirty-one of the fifty states had established

guidelines for crisis intervention procedures, including restraint. The extent of the

regulations provided, however, varied greatly. Only four states provided very extensive

guidelines, while other states were much less detailed and provided little guidance to

schools and districts. Conversely, several states are still in the process of developing and

or revising their policies and guidelines. An alarming fourteen states reported not having

a policy or guidelines in the use of restraints (e.g., Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, Idaho,

Indiana, Missouri and Ohio) and instead designated the responsibility to the individual

school districts. The one commonality found among the thirty-one states that had

guidelines set in place was the language specifying that restraints were only authorized

10

for emergency situations, and/or when the student poses a threat to themselves or to

others. In addition, there was an apparent presumption that restraint procedures would be

used primarily with students with disabilities.

The results of the reports by Ryan et. al (2009) as well as, the results by the

Government Accountability Office 2009, the Council of Parent Attorneys and Advocates

(2000), and the National Disability Rights Network (2009), trigged national attention and

a hearing by the U.S House of Representatives Committee on Education and Labor on

May of 2009 (Peterson, 2010). As an outcome of the reports and hearing, two bills were

introduced to the U.S. Congress. In December 2009, Representative George Miller and

Cathy McMorris introduced to the House of Representatives the “Preventing Harmful

Restraint and Seclusion in Schools Act” (H.R. 4247, 2010), which requires all school

staff using restraints be trained to the House. In March 2010 the bill passed. The very

similar congress bill S. 3895, however, is still in Senate committee (S.2860, 2010).

Proponents of the bill believe that the Keeping All Students Safe Act, stalled in

Senate, because it was significantly different than the House bill in that it allows schools

to include restraint and/or seclusion in the Individuals Education Plan (IEP) and Behavior

Support Plans (BSP) (Handle With Care Newsletter, 2011). Although, there is still no

federal regulations on restraints, experts believe that portions of the bill will at some time

become federal law and are encouraging states and their school districts to develop and

implement policies and procedures in regards to restraint (Peterson, 2010).

Some states and departments of education (DOE) have taken the experts’ advice

and developed state and district policies. One DOE is Nebraska. Although, Nebraska has

11

seen very little restraint abuse, the Nebraska Department of Education developed a

technical assistance document, which highlights the policies and procedures that

Nebraska schools should implement in order to avoid restraint abuse. The Nebraska

Department of Education believed that putting in place consistent polices as well as

appropriate training for staff members would help avoid problems that may arise in the

future (Peterson, 2010).

The technical assistance document created by the Nebraska Department of

Education detailed the ten essential elements of the policies and procedures that address

restraints and seclusion (Peterson, 2010). The document stated that the components can

be reordered, but the policy must incorporate all ten. The ten were as follows: 1.

Definitions of key terms. 2. A rational for the need of the policy. 3. The focus of

prevention (how interventions will be implemented to decrease the need of restraints). 4.

The purpose of employing restraints or seclusion. 5. Staff training requirements. 6. Time

lines or the amount of time restraints or seclusion should be used. 7. Documentation of

the incident. 8. Debriefing on what happened and what could have been done better. 9.

Reporting to parents. 10. The supervision and oversight of the incidence. Although, the

Nebraska Department of Education has implemented policies and regulations for their

school districts to follow, there has been no state policy implemented (Peterson, 2010)

Nebraska is one of many states who have yet to develop laws regarding restraints.

According to policy makers such as, Secretary Duncan (2009) it is only a matter of time

before states will be required by federal law to have policies in place. Therefore, school

12

districts should begin to modify or draft policies now “rather than rushing through

creation of such policies following future federal mandate” (Peterson, 2009).

Death by Restraint

Every year people die while being restrained (Kutz & US Government

Accountability Office, 2009). According to the work of Paquette (2003), the majority of

these deaths occur with restrained individuals, while being taken into custody by law

enforcement. Other sudden deaths by restraints involve people in detention or residential

treatment programs.

Although, there is no reliable data on the number of injuries and deaths that are

caused by restraints on children, the Child Welfare League of America (2002) estimates

that between eight to ten deaths occur every year as a result of improperly performed

restraint procedures. One report identified 142 restraint-related deaths across 30 states in

schools and mental health facilities over a ten-year period long period. A recent series by

Hartford Courant, a Connecticut news team, reported 50-150 deaths of all age groups

each year as a result of deaths (Goldman, 2007). Of these deaths, it is believed that about

a third were due to the improper implementation of restraint procedures, resulting in

death by asphyxia or suffocation (Child Welfare League of America, 2002). However,

there is a great deal of confusion about the cause and circumstances’ surrounding

restraint-related sudden death, one explanation is “in-custody death syndrome.” What is

known, however, is that there is a higher rate of sudden death during restraint encounters.

According to Paquette (2003) ‘in-custody’ death syndrome was first used to

describe deaths where there was no apparent cause other than a police arrest. Law

13

enforcement agencies argued that these individuals exhibited a form of behavioral

disturbance that went beyond the distressed state that they normally face. This extreme

behavioral is referred to as "excited delirium" and includes behaviors such as agitation,

excitability, paranoia, aggression, great strength, and numbness to pain (Mash et al.,

2009). When confronted, these individuals can become oppositional, defiant, angry,

paranoid, and aggressive (Castelo, 2003). Dr. Corey Slovis, an emergency medicine

professor at Vanderbilt University of Medical Center, described the “excited” individuals

as, “Wild and Bizarre [and] are often running down the streets, screaming, and sweating

until dehydration” (Goldman, 2007).

There are many known causes of severe behavioral disturbance like: infection,

brain tumors, heat exhaustion, and illegal drugs, psychiatric medications, but according to

Paquette (2003) excited delirium is an unknown medical condition that is not recognized

by the American Medical Association as a medical or psychiatric condition. The

National Association of Medical Examiners, however, does recognize it and it is used by

medical examiners in many major cities (Paquette, 2003).

A study by Mash et al. (2009) supports the National Association of Medical

Examiners notion that excited delirium is in fact a medical condition. The study showed

that excited delirium is a medical condition that can be detected by apostasy and

“unexplained” deaths are not always a result of “excessive use of force” by law

enforcement. The study (Mash et. al., 2009) argues that there is often a “tendency to

confuse proximity with causality, [especially]…when the necropsy fails to disclose an

anatomic cause of death.”

14

Mash’s et. al (2009) reviewed 90 excited delirium cases and reported that

although none were reported to be anatomic deaths, each case reported one or more of the

following: “catecholamine-induced cardiac arrhythmias, restraint or positional asphyxia,

or adverse cardio-respiratory effects of conductive energy devices (e.g., TASER).”

Mash’s et al., concluded that excited delirium can be medically found by the

“identification of postmortem biological markers” specifically the analysis of the

dopamine transporter and the heat shock protein. Combined this with the descriptions of

the decedent's behavior prior to death--one can reliably associate the sudden death with

the excited delirium syndrome. The study continued by stating that those who die

suddenly by excited delirium are already medically unstable and in a rapidly declining

state and already have a high risk of mortality even with medical attention or the absence

of restraints. Despite the recorded research by Mash et al., there is a lot of controversy in

regards to the use of this syndrome/theory to explain sudden death while restrained.

Opponents of excited delirium theory, such as The American Civil Liberties

Union (ACLU) (2009) say there is no proof that someone can be “excited to death”. The

ACLU believes that the theory is “being exploited and used as a scapegoat for police

abuse” (Castello, 2003). They do not believe that these people die from some

“mysterious” syndrome but from abuse, and inappropriate and overuse of force and

restraints that should have been avoided. The ACLU believes’ that being confronted with

excessive force results in psychological stress, which causes further physiological

reactions like, adrenaline release, increased heart rate, temperature, and strength, thus

15

resulting in death (Castello, 2003). The ACLU (2009) strongly believes that most incustody deaths are the result of excessive force and improper restraint techniques.

Model of Best Practices

Minimizing the use of physical restraints on students with special needs should be

a key goal for both schools and law enforcement agencies. There are two main studies,

which describe the implementation of an intervention program to decrease the use of

restraints. Both studies were proven successful in their endeavors.

Grafton Winchester Facility

According to research conducted by Sanders (2009) using a multi-component

intervention program will help to reduce the use of physical restraints thus decreasing the

possibility of bodily harm and psychological effects. Sanders (2009) study described the

outcome of a 2004 mandate that challenged Grafton’s Winchester facility to create an

individualized facility plan to minimize restraints. The facility served approximately 73

children and 43 adults in both a day school and residential program. The children ranged

from 7 to 21 years of age and had varying levels of autism and/or intellectual disabilities,

including psychiatric conditions and significant behavioral challenges. The participants in

this study were from 21 community based group homes and two school sites. They

lacked safety awareness and displayed severe aggressive behaviors thus requiring a 24

hour residential support. The facility used de-escalation strategies; however, when those

failed they used physical restraints to maintain safety in emergency situations. Prior to

the mandate, the Winchester facility employed 260 restraints equaling about 3800

minutes during a one month period.

16

The Winchester facility created a four-component intervention process. The first

component consisted of a reporter, who was responsible for talking to employees about

reducing the use of physical restraints. The reporter would then take the feelings,

reservations, concerns and or suggested tools to the chief executive to design an action

plan. The next three components were staff training, increased management support, and

a formal system to monitor restraints. Although, all of these components are important,

staff training and management support were viewed as being the most effective.

The facility found that training was a vital component. It became apparent that if

restraints were to be eliminated then it needed to be replaced with another tool. Staff

members underwent a 2 hour training, which taught philosophical perspectives and

various non-physical strategies (Sanders, 2009). The foundation of the training focused

on learning how to support and comfort an individual experiencing emotional distress

versus trying to control the individual. The training reviewed in Sanders research (2009)

was based on work by Huckshorn, who stated:

If you are looking at facilitating the growth or rehabilitation of kids who have

already been traumatized and have not had good role models, and you’re trying to

make them productive adults, you don’t do that by forcing, coercing, controlling,

and ruling them (Sanders, pp 218, 2008).

In addition to the philosophy training, employees underwent extensive training

that consisted of lecture, demonstration, and practice on ‘extraordinary blocking’

techniques instead of restraints. Extraordinary blocking techniques include, using

pillows, cushions, bean bags and other soft objects to support the individual, but also

17

protect the staff members involved. The items are to be used by holding them up to

lessen the impact and or deflect kicks, hits, slaps, bits etc. The training taught basic

techniques and stressed the importance of each treatment team to identify what works

best for each individual. These techniques, however, were not full proof. For example,

Sanders (2009) found that staff still complained that they were being scratched on their

hands, which were not protected.

The third component, which was also viewed as being very essential to decreasing

the use of restraints, is the physical presence and support by the management. This

meant that management officials, such as the executive director and administrators,

would be there to support staff members in an emergency situation, in addition to the

normal on-call schedule. In order for this to be successful staff members were instructed

to call for assistance when clients were first showing signs of difficulties. Restraints

could then be avoided with additional support to assist in de-escalating the situation. The

managers were there to provide both direct support, and also to observe the staff

members and give positive feedback and guidance. Sanders (2009) research found that

this component was successful because at any given moment during any time of the day

or night a manager could be contacted.

The last component involved creating a formal system of processing restraints.

The goal of the system was to debrief the individuals who were involved. The process

included how to avoid similar situations in the future and how to identify what additional

supports were needed. Questions such as “How did you de-escalate the situation?” and

18

“What would you need next time to be able to effectively use extraordinary blocking?”

were asked during the debriefing (Sanders, 2009).

The four-component program studied by Sanders (2009) almost eliminated

physical restraint. There was a 99.4% reduction in physical restraints from 2005 to 2008.

Although, it is difficult to say which component contributed most to such dramatic

results, it can be concluded that the four-component interventions, which did not require

the use of restraints was extremely effective.

Luiselli’s Study

Another study conducted by Luiselli (2009) also found non-restraint interventions

effective. As in Sanders (2009) study, Luiselli’s study found that early intervention was

essential. The study focused on assessing antecedent conditions associated with restraint

and changing them so that they no longer produced restraint-provoking behavior. The

staff members were taught how to detect behaviors that indicated that the individuals

were becoming upset, which often predicted aggression. When observing the antecedent

behaviors the staff used individualized strategies such as: taking time away until the

individual was composed, allowing access to novel activities, and strategically placing

students so there is less interaction with peers. In addition to staff training, students also

underwent functional communication training, which taught them how to request a break

from situation that causes them to become frustrated.

Another approach used by Luiselli (2009) was to decrease the duration of restraint

because maintaining physical restraint can be problematic if a person is unable to calm

down quickly. One way she proposes to do this is by establishing a fixed-time criterion.

19

Her research showed that a person’s total exposure to physical restraint could be

minimized by stopping the procedure after a fixed-time has elapsed, instead of waiting

until certain behavior is exhibited. This is similar to findings by Singh & And (2009)

who found that a brief one minute physical restraint was more effective than a three

minute physical restraint, in controlling self-injurious behaviors in a 16-year-old

profoundly retarded girl. In other words, the end results of the study found that if

restraint is necessary it is more effective if the restraint lasts less than 2 minutes.

Controversy on the Use of Restraints

Physical restraints, which are used to help reduce or eliminate a student’s

aggressive behavior is a very controversial topic. Professionals, who use restraints in

schools, argue resolve the crisis better than other interventions and are thus needed in

emergencies when an individual becomes a threat to him/herself or to others (Miller et

al., 2006). Studies such as those conducted by Lamberti & Cummings, 1992; Measham,

1995; Miller et al., 2006; Rolider, Willimas, Cummings & Van Houten, 1991 assert that

when a student becomes extremely aggressive there is no other way to de-escalate the

situation, but to use restraints (Handle With Care, 2011). They argue that physical

restraint is effective in decreasing self-injurious and aggressive behavior and are

necessary in order to insure the safety of the individual or those around him/her.

According to research by Fahlber (1991), physical interventions, such as

restraints, play an important and beneficial role in re-parenting youth, who were not

taught how to set limits because of the absence of parenting. The student thus learn that

actions have consequences. Proponents also point out that there are many positive

20

outcomes of successful restraint that are overlooked. For example, there have been

many reports where teachers had to use restraints in order to protect a student from

assault from another student. They say that the teachers’ right to restraint insures safe

environment for all kids. (Handle With Care Newsletter, 2011). Therefore, proponents

for restraints argue that they are used to benefit the individual (Stirling & McHugh,

1998).

Police departments are also advocates for restraints. According to research by

Brave & Peters (1994) all police departments use some form of restraint. The type of

restraints must follow the standards created by law. The use of restraints are controlled

by federal law, state law, county and departmental policies, as well as manufacturer

instructions (Brave & Peters, 1994).

The federal law states that placing a person in handcuffs impinges on that person's

fundamental right of liberty. Police can only use handcuffs when there is a lawful

justification for doing so. An officers use of force against a citizen must be

“…objectively reasonable, based upon the totality of circumstances” (Brave & Peters,

1993). There are three factors that determine the “totality of circumstances.” The

severity of the crime and the immediate threat to the safety of officers and others must be

considered, as well as, whether the suspect is resisting or attempting to evade arrest. If

the officer uses more force than necessary, the officer is in violation of the Fourth

Amendment right to be free from unreasonable seizures or use of force. If found liable

the officer could face Federal prosecution (Deprivation of Rights Under Color of Law).

21

In addition to federal laws, state laws also exist. State laws typically follow

federal mandate, however some states will require officers to use leather straps on

mentally ill patients instead of metal handcuffs. Departments are also allowed to make

requirements for their officers and their requirements are usually more specific, but they

have to be in accordance of federal and state law. For example, the Chandler Police

Department of Arizona (2010) have a manual that describes the proper used of handcuff

restraints. According to their department statue, handcuffs are to be used on all prisoners

except when: doing so knowingly aggravate an injury during transport, or when based on

legitimate reasons and sound officer discretion. The policy also details the proper cuffing

technique. The department requires the officers to place prisoners hands behind their

backs, check the tightness of the handcuff- stipulating that they should be lose enough to

slide up and down the arms without slipping off their hands and requires that even if the

person is handicapped, sick, and/or injured: if they can be transported in a patrol car then

they need to be restrained. They do, caution their officers to not place prisoners in

restraints if they are in a position that will restrict the person's ability to breathe. The

Chandler Police Department (2010) also encourages officers to consider bringing the

suspects hands to the front of their body if they are in a patrol car for more than an hour.

In order to insure totalities of circumstances are considered, some departments

give very detailed instructions when circumstances include juveniles, pregnant woman,

ill, injured, intoxicated person or an obese person. For example, a Seattle Police

Department (2011) requires pregnant women to be handcuffed in front rather than the

22

back and obese individuals be hand cuffed using two sets of cuffs attached together to

avoid strain.

Police departments argue that policies and procedures are always in place, and

officers undergo extensive training in the use of restraints. They believe that restraints

are not only necessary, but essential for the protection of the officers, the restrained

prisoner and third party individuals.

Opponents of restraints, such as the Council for Exceptional Children (CEC),

argue, that they are used too often in public school settings and should have no place in

schools. They state that applying restraints are not only invasive, but can cause injury to

the person being restrained, as well as the individuals implementing them

(www.cec.sped.org). In addition to the risk of bodily harm, a number of adverse

psychological effects are associated with physical restraint, such as dehumanization,

withdraw, agitation, depression, trauma and re-traumatization (Sanders, 2009).

According to Luiselli (2009) physical restraints can also provoke, and in some cases

maintain, problem behaviors because it functions as a positive or negative reinforcement.

Ryan & Peterson (2004) agree, stating that there is very little research that proves

physical restraint as a behavior modification strategy. They believe that proponents use

these techniques despite the lack of research because it has historically been used for this

purpose and they don’t know other strategies.

Opponents of restraint instead believe that schools should create new, or modify

existing policies and procedures in regards to physical restraint, as well as offer non-

23

restraint training to all staff members involved in students with aggressive behaviors

(Peterson, 2010).

The use of restraints is a very controversial topic and both proponents and

opponents have founding arguments. It can be concluded that proponents believe the use

of restraints are affective and necessary in emergency situations especially in regards to

criminals being taken into custody. Opponents, however, state restraints used on

juveniles, especially with those whom have special needs, should only be used for a

minimal amount of time and only when all other options have been exhausted.

24

Chapter 3

METHODOLOGY

The purpose of this study was to address the use of restraints by law enforcement

agencies on students with special needs and provide training on alternative researchbased methods that can be employed.

The author has personally experienced the overuse and/or “abuse” of restraints

used on juveniles. On numerous occasions, the author observed peace officers relying

heavily on restraints, such as handcuffs, to get juveniles with special needs to obey their

and/or the teachers orders. In one case, a 10 year old boy was detained using mechanical

restraints and escorted off school grounds even though he was fully complying with the

school staff and police officer.

The author being very distraught over continual situations like the before

mentioned, started to ask peace officers general questions about the amount of training

they received on working with juveniles and more specifically with juveniles with special

needs. The author relied heavily on her sister, who was a peace officer for answers. The

author discovered from interviewing her sister and from informal questions that her sister

sought from fellow officers, that both new and senior officers received very little training

in working with juveniles with special needs and they all thought the training would be

very beneficial.

The author, a special educator, has a personal commitment to ensure that students

from different cultures and learning abilities feel cared for, stimulated and challenged and

most importantly feel respected, safe, and are treated with dignity. The author, shocked

25

by the informal answers given by the peace officers and by the increase of headlines of

kids with special needs being a victim to alleged police brutality, knew that research had

to be conducted in order to develop awareness and training for peace officers.

Participants

The ten participants for this research were chosen from Tehama County. All of

the officers that participated in this project (exception of 2) at one time worked for

Tehama County. Tehama County is located in rural Northern California.

Tehama County was the focus location because the author was able to recruit

volunteers to participate. The author had difficulty-getting approval from a law

enforcement agency to implement the training because it had to be presented to the City

Council for approval. Since, the City Councils agenda’s were filled, the author sought

volunteers. All the participants (exceptions of 2) in this study volunteered because they

knew and/or at some point worked with the author’s sister, whom is a peace officer. The

participants who volunteered were fully aware that the training they received was not

department approved. Although, most of the peace officers were from the same location,

the academies where they received their initial training and their prior law enforcement

experience varied. For the purpose of confidentiality officers names have been changed.

Training Design

The design for this study was developed through the authors personal

observations of the overuse of restraints on juveniles with special needs at her school, as

well as, informal conversations with the author’s sisters, whom is a police officer, and

with the author’s school districts police department.

26

As previously mentioned, after talking to the peace officers, the author learned

that the officers did not “know what to do.” One officer stated that when he receives

calls from schools in regards to special needs children he relies heavily on the special

education teacher and administrator for assistance because “they [special educators] have

been trained” and he “[has] not.” This concerned the author, who is a special educator,

because she was not trained in restraint and was instead directed to call law enforcement

in “out of control” situations. Shocked by learning that peace officer had little if any

training in regards to juveniles with special needs/mental illness probed her to research

the amount of training and the type of training officers received on working with

individuals with special needs.

The author began to conduct informal interviews as well as in depth research on

effective behavior management techniques as well as safer and less invasive forms of

restraint in order to develop a effective, comprehensive program that would apply to all

peace officers. After the initial research, the author developed a survey to get an in depth

understanding of the training peace officers received in working with kids with special

needs.

The results of the survey drove the content and the organization of the training.

The training program consists of five parts: background information, identification, deescalation strategies, safe restraints research, and safe restraint training. When

developing the five parts of the training it was essential to use appropriate research-based

theories and teaching strategies gained from the literature review. In order for the target

audience to develop the skills necessary to de-escalate a challenging situation and/or

27

safely restrain an individual with special needs, it was imperative in the training to

present a historical perspective of the problem in regards to restraints, so the trainees

could see that the information is founded by research. Participants all needed ample time

to practice the target skills because they are multifaceted and mastery is essential. Most

importantly feedback was given, so a comprehensive understanding was gained and

improvements were made.

The intended learning outcome of this project was that peace officers would have

a solid understanding of the nature of learning disabilities, behaviors that are associated

with the disabilities, types of restraints, effective de-escalation strategies, as well as safe

restraint techniques. The skill and task training will apply to any peace officer and will

provide a foundation they can use when working in challenging situations with juveniles

with special needs or mental illness.

Pre-Survey

The author developed a survey to give to peace officers, using Survey Monkey

(See Appendix A). Survey Monkey, is an online survey program, which allows the

designer to create, distribute and analyze surveys. The author choose Survey Monkey

because of the ease of accessibility. The author worked closely with her sister, who is a

police officer, to make sure the survey questions and answers were relevant. For

example, in regards to amount of training officers received, the author choose to give

hourly options, because police officer trainings are usually always 4 hours (half day), 8

hours (full day), or 9+ hours (more than a day). The survey consisted of nine multiplechoice questions and one fill in question, making the survey simple, yet very

28

informational. The purpose of the pre-survey was to collect information on the amount

of training officers have had in working with juveniles with and without with special

needs, as well as the amount of non-restraint training, such as de-escalation strategies

they have received. The author also wanted to know how confident the officers felt when

responding to calls involving juveniles with special needs. Most importantly, the author

needed to know if they felt a training on working effectively with juveniles with special

needs would be beneficial. The answers the officers provided were the foundation for the

training.

Training

The information collected from the survey and research conducted was compiled

into a solid structured training program for police officers. The training is called,

Restraining Restraints: Decreasing the Use of Restraints on Individuals with Special

Needs and Mental Illness” and it specifically targets law enforcement personnel. The

training set forth below, applies to behaviorally problematic situations with kids who

have special needs.

The training was a PowerPoint presentation (See Appendix B, pp 42) that was

broke into five parts: Part 1 Background Information, Part 2: Identification, Part 3: Deescalation strategies, Part 4: Safe Restraints Research and Part 5: Safe Restraint Training.

When developing the five parts of the training it was essential to use appropriate

research-based theories and teaching strategies gained from the literature review. In

order for the target audience to develop the skills necessary to de-escalate a challenging

situation and/or safely restraining an individual with special needs, it was imperative to

29

build background knowledge, so they could see that the need of training was sparked by

both historical research and officer request. It was critical to provide time for the

officers to practice the target skills learned and most importantly give feedback. The

PowerPoint training provided the trainer with a day-to-day agenda as well as the

sequence of the training.

The training is appropriate for peace officers of any group size, with the

understanding that active participation of attendees is vital. A projector and projector

screen was required, as well as internet access. The training took place in a large location

with seating for each attendee, as well as a designated area for practicing safe-restraint

techniques. All participants had a print out of the PowerPoint training and a writing

utensil to take notes. In order to insure that each concept covered was understood and the

desired learning outcome was met, the training was introduced across two eight-hour

days. The training session covered the following topics:

Day 1

Part 1: Background Information (See Appendix B, pp 43)

Day one began with the objectives of the training, a brief snap shot of why it was

important and also the definitions of key terms that were going to be used throughout the

training. After a brief introduction of the training, the trainer presented the officers with a

more in depth look at why the training was essential. The trainer introduced statistics and

research obtained from the author’s literature review. The most controversial topic

presented was the “Excited Delirium” theory.

30

Both proponents and opponents of the theory were introduced (See Appendix B,

pp 223). During the proponents section, all three officers discussed that they believe the

theory to be true. In fact one officer stated that he became aware of the theory after he

had been involved in an “altercation with a criminal that suddenly died for no known

reason.” During the opponents section the officers were upset by the ACLU’s position

that police were using the theory as a “scapegoat for police abuse.” One officer stated,

“[He] was sick of people blaming cops for criminal’s actions.” Another cop continued

saying, “[They] were tired of citizens thinking cops are on power trips and want to

intentionally physically harm people.” The trainer reminded the participants that it is

important to understand both positions in order to be able to make a better argument for

or against the issue.

Part 2: Identification Training (See Appendix B, pp 50)

The trainer started the second part of the training by reading, “Welcome to

Holland, (See Appendix C, pp 81)” a story written by a parent on what it’s like to raise a

child with a disability. After reading the story the trainer asked officers what they

thought about it. Officer Holmes stated, “[She] felt that raising a child with a disability

would be stressful and beyond difficult,” but added that “the way the parent embraced the

situation was honourable and could be applied to many difficult situations in life.” The

trainer continued with the different types of disabilities and how to identify each. The

officers seemed very interested in the different types of disabilities and asked questions

such as, “How do you diagnose an individual with a learning disability?” “Do they look

31

different they me and you?” and “What are some reasons that individuals end up with

learning disabilities?” to name a few.

After the officers received an overview of the different types of disabilities and

the characteristics associated with each, the trainer provided the officers with a few

scenarios in which they had to identify the learning disability. Officer Jackson, stated

that the “Scenarios helped [him] apply what he learned....and [he] liked it.” Officer

Holmes and Angley agreed. The day concluded with a summary of the day.

Day 2

Part 3: De-escalation Strategies (See Appendix B, pp 62)

Day 2 started with the trainer reading a quote called, “Attitude” (See Appendix B,

pp 62 ) and continued by introducing de-escalation strategies that should be used when

working with an “angry” or “out of control” individuals, especially ones with a learning

disability. The trainer then discussed the importance of managing oneself. Officer

Jackson asked, “Why should I have to worry about myself, shouldn’t I be worrying about

the situation at hand?” The trainer explained, “...People react instinctively to anger and

when we do so, we typically react inappropriately and if we can learn to calm ourselves

down, then we enter the exchange with more control.” The officers responded with nods

of agreements.

The training continued with presenting strategies such as, relating to the

individual in crisis, tone of voice, body language, response time, repeat of directions etc...

At one point, officer Angley stated that, “[He doesn’t] have time to sit there for 15-20

minutes to try to de-escalate a situation.” The trainer replied, “[She] understands that

32

officers are overworked, but if using de-escalation strategies are working, it shouldn’t

matter if it takes 15 minutes or an hour because all individuals have a right to be

protected and respected and all the time in the world is worth saving someone’s life.”

The training ended, with the trainer providing time for the officers to practice the newly

taught de-escalation strategies.

Part 4: Safe Restraint Research (See Appendix B, pp 69)

The trainer presented the participants with two case studies that showcased

effective and efficient alternatives to restraints. The trainer emphasized that the methods

presented should always be tried first before other restraints methods (physical, chemical,

and mechanical), be used unless immediate danger and/ or threat is present. Officer

Holmes, commented that, “The research was impressive..., but was concerned that [they]

are not equipped with the props needed for safe blocking techniques.” The trainer

responded by stating that the officers could, “Carry a small pillow with a hand strap sewn

on the back...or could use whatever soft objects they had in reach.” The officers and

trainers adjourned for a 45 minute lunch break prior to the physical restraint training.

Part 5: Restraint Training (See Appendix B, pp 77)

When the group re-assembled the trainer had the three officers’ work together to

simulate a possible emergency situation. One officer acted like the “out-of-control”

individual, while the other two officers worked together to try resolve the situation using

all the methods they were taught. The officers were instructed to first use de-escalation

strategies, then blocking techniques, and lastly safe restraints, which included a basket

hold-lasting only 2 minutes or less. The officers took turns in each position.

33

According to the trainer, the hardest aspect of the training was having an officer

act “out-of-control.” The officers were very timid and gave little resistance. On a couple

of occasions the trainer had to step in and play the part. Officer Jackson commented that

he felt the training was “beneficial” and he felt more “confident and prepared.” Officer

Holmes, added that she thought she could “...apply the strategies to most of [her] calls”

even those that are not “associated with juveniles or individuals with special needs.”

Officer Angley, agreed with the other two officers and was “...eager to employ the

strategies.”

Layout

Throughout the training, the trainer provided ample time for questions and

clarification. In addition, after parts 2-4, time was given to practice the newly taught

strategies covered. The training ended by combining the de-escalation and safe restraint

strategies together in a role playing exercise.

The training was completed in two consecutive days. Ideally, if the training could

not be completed in two consecutive days, then it could be spread across one week. This

schedule will insure a complete understanding of the background information, concepts,

and techniques taught, and allow the time necessary for practice.

The two training session included direct instruction utilizing lecture, discussions

and role playing. Participants were expected and encouraged to actively participate in

discussions and role plays, as well as any activities that were set forth in the training.

Participants took notes and were required to apply the new concepts and strategies to

outside experiences. At the conclusion of each part, the trainer asked questions to assess

34

understanding, as well as required participants to respond to scenarios using the newly

gained concepts. The trainer asked participants to volunteer, as well as, called on random

participants to share their answer to the scenarios. For Part V: Safe Restraint Training, the

author coached the officers by showing and reminding them the skills they were taught.

The author also shadowed the police officers making sure she was readily available for

questions or if she needed to make adjustments to the holds or positions of the officers.

Lastly, the author provided feedback to the participants, so they knew what worked and

what needed continued practice.

Post-Survey

After the training, each participant was required to take a post-survey. The author

developed a survey to give to peace officers participants, using Survey Monkey (See

Appendix E, pp 81). Survey Monkey, is an online survey program, which allows the

designer to create, distribute and analyze surveys. The author chose Survey Monkey

because of the ease of accessibility. The author used the pre-survey, as well as the target

learning outcome, as a guideline for the post-survey questions. The post-survey also

consisted of nine multiple-choice questions and one fill in question, making the survey

simple, yet very informational. The questions were very similar to the pre-survey, but

instead focused on the police officers confidence level working the juveniles with and

without special needs after receiving the training. The author also asked how confident

they feel (after the training) in implanting safe restraints and de-escalation strategies.

Most importantly, the post survey had officers rate the success of the training and the

expertise of the trainer. Chapter 4

35

Chapter 4

CONCLUSION/RECOMMENDATIONS

The need for this research came about when the author observed the overuse

and/or “abuse” of restraints used on juveniles. According to the author, on numerous

occasions, peace officers were observed putting forth little if any effort in using nonrestraint methods such as, de-escalation or “safe” restraint strategies to resolve conflicts

with juveniles with special needs.

The author, a special educator, has a personal commitment to ensure that students

from different cultures and learning abilities feel cared for, respected, safe, supported and

are treated with dignity. The author being very distraught over continual situations like

the before mentioned, started to ask peace officers general questions about the amount of

training they received on working with juveniles and more specifically with juveniles

with special needs. The author discovered that both new and senior officers received very

little training in working with juveniles with special needs and they all thought the

training would be very beneficial.

The author shocked by the informal answers given by the peace officers and by

the increase of headlines of kids with special needs being a victim to alleged police

brutality, knew research and training for police officers was crucially needed. The author

used the informal interviews to develop a survey, using Survey Monkey, for police

officers, so she could gain a better understanding of the training they have undergone in

relation to juveniles, juveniles with special needs and on non-restraint and “safe” restraint

36

techniques. The author also wanted to know the officers confidence level in working

with the before mentioned population and using non-restraint and safe restraint strategies.

The purpose of this research was to address the use of restraints law enforcement

agencies on students with special needs and provide training on alternative researchbased methods that can be employed. The author found through her research that both

unseasoned and veteran peace officers reported receiving very little training in working

with juveniles, and even less in working the individuals with special needs. Although, 8

out of 10 officers reported that they would feel “confident” when responding to an

elementary school call regarding an “out of control” student whom was in special

education, zero officers reported feeling “very confident.” Despite the majority of

officers feeling confident in responding to emergencies involving kids with special needs

all ten officers felt that training on identification of special needs, de-escalation strategies,

and “safe” restraint techniques would be “very beneficial.”

Three out of ten officers who took the initial survey volunteered to partake in the

two day Restraining Restraints training. During the training the author was confronted

with many heated discussions. The main issue that continued to arise was officers stating

that they “Don’t have time” to “de-escalate” situations. The author reminded the officers

that it was their civil duty and the 4th amendment rights of the students to have all

strategies exhausted before using mechanical, physical or chemical restraints. The author

also asked the officers how they would feel if their child with special needs was

handcuffed, maced or physically restrained by an adult without trying other strategies.

This analogy by the author seemed to be very effective in getting the officers to

37

understand the importance of using de-escalation strategies. Although, there were times

the officers were resistant, at the end of the training they seemed to appreciate and

recognize the need to use other methods/strategies and to not rely so heavily on restraints.

After the training the officers took a post-survey, using Survey Monkey. The

survey showed that the three officers reported an increase of confidence in working with

juveniles, juveniles with special needs and using non-restraint techniques such as, deescalation strategies, and “safe” restraints techniques, such as blocking. The three officers

also agreed that the training was very beneficial and the professionalism and knowledge

of the presenter was excellent. In conclusion, the Restraining Restraints: Decreasing the

Use of Restraint on Individuals with Special Needs, training was effective in increasing

the confidence level of peace officers when working with individuals with special needs.

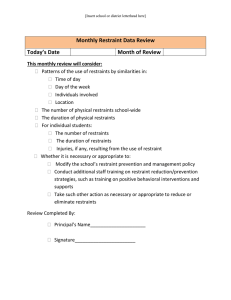

Recommendations

It is strongly recommended that further research in the area of police officers nonrestraint and “safe” restraint techniques on students with special needs, be continued.

Future training should include a larger and more diverse population. Continued training

should be provided over the years to match new research based methods and meet the

very large and diverse special needs population. Police academies should implement

training on identification of individuals with special needs, as well as de-escalation and

safe restraint strategies. Police departments should mandate and include in their

department handbooks, guidelines to follow when working with juveniles with special

needs. The department chief/sergeant should ensure the implementation of these polices.

38

It is also strongly recommend that every state establishes written laws and

protocols which require law enforcement agencies to follow. Every police department

should make the policies available to the public, so parents and school personnel are

aware of the protocol. The department should specifically identify how calls involving

juveniles with special needs are monitored. Incidents, especially those involving injures,

should be reported to an outside agency on a regular basis. Departments need to assess

the accuracy of the data and set in place interventions if needed when data indicates

overuse or potential abuse of restraints involving students with special needs. States

should also develop policies for schools regarding restraints, so they can assist law

enforcement in emergency situations.

39

APPENDIX A

/w EWDgLirdKQA

/w EPDw ULLTIw M

Police Officer Training PRE-Survey

Exit this survey

1. About how many hours of TRAINING (not what you have learned by

experience, but what you have been directly taught) have you received on

working SPECIFICALLY with individuals who have disabilities, (e.g.

Autism)?

None

1-4

5-8

9 or more

Other (please specify)

2. About how many hours of training have you received on working

SPECIFICALLY with juveniles (ages 0-12)?

About how many hours of training have you received on working

SPECIFICALLY with juveniles (ages 0-12)? None

1-4

5-8

9 or more

Other (please specify)

3. About how many hours of training have you received on working

SPECIFICALLY with juvenile individuals with mental illnesses (e.g.

Oppositional Defiant Disorder)?

None

1-4

5-8

9 or more

40

Other (please specify)

4. Considering the training you have received, how confident do you feel

working with children ages 1-12 whom have disabilities, such as Autism?

Not Confident

Somewhat

Confident

Very Confident

Confident

5. Considering the training you have received, how confident do you feel

working with children ages 1-12 with mental illnesses, such as

Oppositional Defiant Disorder?

Not Confident

Somewhat

Confident

Confident

Very Confident

6. Considering the training you have received, how comfortable would/do

you feel if/when responding to a elementary school call regarding an “out

of control” student who they tell you is in a special education class?

Not

Comfortable

Somewhat

Comfortable

Comfortable

Very

Comfortable

Comment:

7. How beneficial would a training be, that was SPECIFICALLY designed for

teaching de-escalation strategies and “Safe” restraints (e.g. blocking, the

basked hold etc…) for juveniles with disabilities, such as Autism, and

mental illness?

Not Beneficial

Beneficial

Somewhat Beneficial

Very Beneficial

Comment:

8. How many hours of “safe” restraint training (e.g. blocking, the basket

hold etc…) have you undergone?

None

1-4

5-8

9 or more

Other (please specify)

41

9. How many hours of de-escalation strategy classes have you undergone?

None

1-4

5-8

9 or more

Other (please specify)

10. How many years of service do you have?

OPTIONAL: What county do you work for?

How many years of service do you have? OPTIONAL: What county do you work

for?

Done

Powered by SurveyMonkey

Create your own free online survey now!

42

APPENDIX B

Restraining Restraints Training PowerPoint

43

Restraining Restraints

Decreasing the use of Restraints

on Individuals with Special Needs

and Mental Illness

By: Heather Gold

B.S. Human Development

Multiple Subjects Credential

Mild/Moderate Credential

Part I

Background Information

• Objectives of training

• Why is this training important?

• Definitions

• Types of Restraint

44

Part I

Background Information

• Statistics

• How and why deaths are occurring?

• Controversy of restraints

• Pros and Cons of restraints

Objectives of Training

Continued

• Identify the characteristics of different

disabilities

• Learn de-escalation strategies

• Employ safe “restraint” techniques

Why is this Training Important?

• The use of restraints on individuals with

special needs and mental illness has been

increasing over the past decade.

45

Why is this Training Important?

• Every year people die while being

restrained and the majority of these deaths

occur while being taken into custody by law

enforcement (Paquette, 2003).

Training Important continued…

• Although, there is no reliable data on the

number of injuries and deaths that are

caused by restraints on children, the Child

Welfare League of America (2002)

estimates that between eight to ten deaths

occur every year as a result of improperly

performed restraint procedures.

Definition of Youth/Juveniles

• Youth and juveniles are one in the same

• They refer to children 0-12 years of age

46

Definition of Special Needs

• Special Needs during this training refers to

individuals with a disability (to be defined later)

and/or mental illness (to be defined later).

Chemical

• Chemical restraint involves using

medication or sprays to control or restrict

and individual’s freedom of movement