Cosmopolitanism and Nationhood in the Political Thought of Thomas Paine Robert Lamb

advertisement

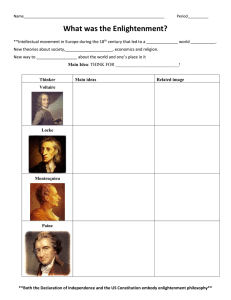

Cosmopolitanism and Nationhood in the Political Thought of Thomas Paine Robert Lamb University of Exeter The project - Reconstruction of Paine’s political philosophy, focusing on key themes (political obligation, democracy and representation, property and welfare, international relations) - To present it as a coherent theory of liberal rights - To show that it is philosophically and historically distinct Cosmopolitanism • Cosmopolitanism construed historically as intellectual tradition, not as singular political theory with set of core principles • Defined (thinly) as belief in global reach of some normative truths/values • Does not necessarily imply rejection of local sovereignty ‘Citizen of the World’: Paine’s Cosmopolitanism • ‘the cause of America is…the cause of all mankind’ • American Revolution/War not just a matter of a nation’s independence • Matter of global justice – British waging a ‘war against the natural rights of mankind’ ‘Citizen of the World’: Paine’s Cosmopolitanism • ‘the cause of America is…the cause of all mankind’ • American Revolution/War not just a matter of a nation’s independence • Matter of global justice – British waging a ‘war against the natural rights of mankind’ • ‘the cause of France is the cause of all mankind’ • French Revolution part of progress towards ‘universal civilization’ • Heralded end of European ‘despotism’ and the emergence of the ‘Great Republic of Man’ Paine on Individual Rights • Consistent commitment to individual rights throughout Paine’s writing: rights to freedom of thought and speech, democratic representation, welfare, property ownership and (latent) rebellion. • Commitment to rights stems from axiomatic belief in human moral equality • Universalistic understanding of rights Paine on National Sovereignty • Dominant interpretation of Paine as radical cosmopolitan (e.g. Dyck, Claeys, Walker) • Suggested contrast with Kant’s state-centric international theory • Yet Rights of Man does contain account of national sovereignty: ‘that which a whole nation chooses to do, it has a right to do’ • The ‘nation’ described as ‘the source of all sovereignty’ – 3rd article of French Declaration of Rights, which Paine describes as ‘the basis of liberty’ Rights of Nations • If nations have the sovereignty Paine claims, then they would seem to have rights of selfdetermination. • These rights of self-determination imply (1) a localised form of political membership that excludes non-nationals and (2) duties of non-interference on the part of other nations, both of which stand in tension with the cosmopolitan sentiments identified. • Can nations deny individual rights (like freedom of speech or religious worship)? Universal Rights and National Sovereignty: a reconciliation • Paine’s position can be rendered coherent - to do so involves subsuming the claim about national sovereignty within the theory of individual rights: national rights to self-determination and noninterference are conditional upon the recognition and protection of individual rights. • First 3 articles of the French Declaration only make sense if this understanding is accepted and individual rights trump national sovereignty. Paine on Liberal Intervention • If nations that are not liberal do not have rights of selfdetermination, do liberal nations therefore have rights (or even duties) to intervene in their affairs? • Paine seems committed to pacifism as a normative ideal but also expressed personal approval (1) for French military aggression against Germany in 1792 and (2) a French invasion of Britain in 1798 • According to Walker, these examples reveal his revolutionary liberalism that differs from Kant’s evolutionary liberalism: ‘Paine was a strong advocate of military intervention to spread democracy’ and aimed ‘to foster or force democratic governance the world around’ Revolutionary Liberalism? • Both of Walker’s examples of Paine calling for military aggression are best interpreted as defensive campaigns. • No evidence that Paine thinks that liberal nations hold any right to interfere in the affairs of nonliberal ones. • Paine’s position is ambiguous but looks similar to that outlined in John Rawls’s The Law of Peoples (1999), which only permits international intervention during times of emergency, which are defined by violations of human rights. Conclusions • Paine is cosmopolitan but he nevertheless defends national sovereignty • His account of national sovereignty only makes sense within his overall liberal individualist framework • Paine distinct within cosmopolitan tradition in his rejection of the impossibility of a world state: his consent-based theory enables the possibility of global governance while withholding its endorsement • ‘Where liberty is not, that is mine…’