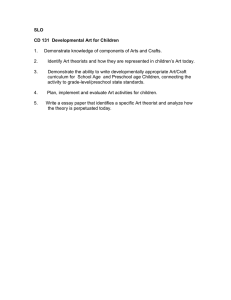

1 Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION

advertisement