Mariely López-Santana, Ph.D. Candidate Institutional Affiliation:

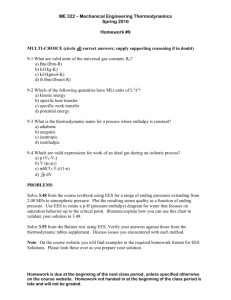

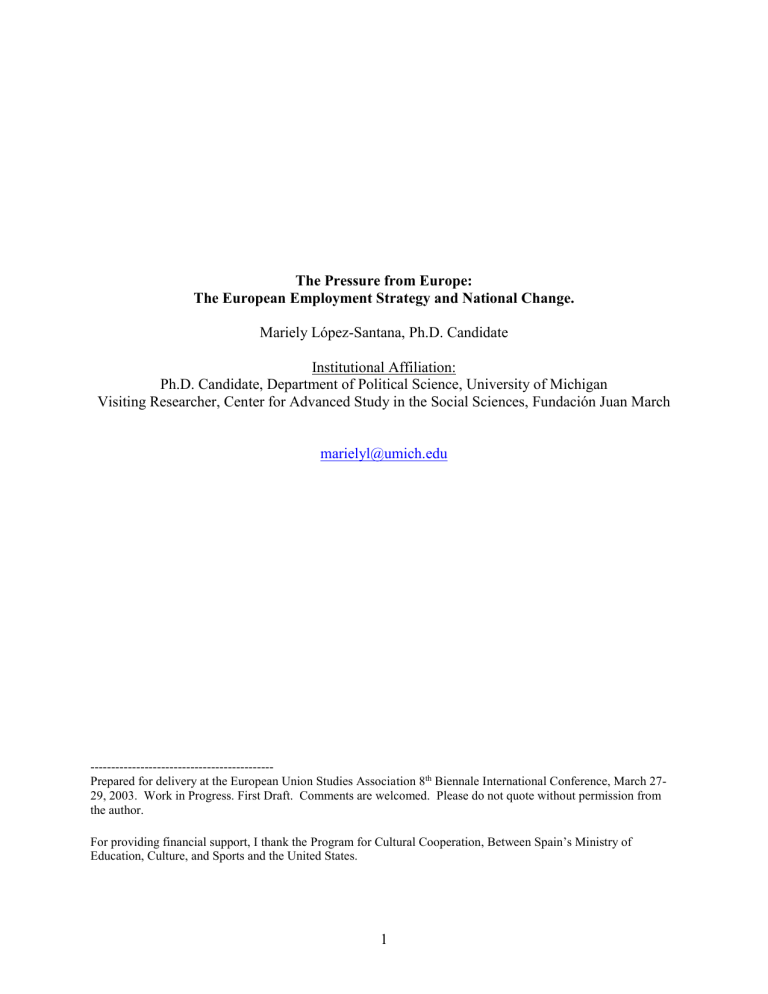

The Pressure from Europe:

The European Employment Strategy and National Change.

Mariely López-Santana, Ph.D. Candidate

Institutional Affiliation:

Ph.D. Candidate, Department of Political Science, University of Michigan

Visiting Researcher, Center for Advanced Study in the Social Sciences, Fundación Juan March marielyl@umich.edu

--------------------------------------------

Prepared for delivery at the European Union Studies Association 8 th Biennale International Conference, March 27-

29, 2003. Work in Progress. First Draft. Comments are welcomed. Please do not quote without permission from the author.

For providing financial support, I thank the Program for Cultural Cooperation, Between Spain’s Ministry of

Education, Culture, and Sports and the United States.

1

The Pressure from Europe: The European Employment Strategy and National

I) Introduction

Since the late 1980’s, there has been growing interest among policy-makers and scholars in the establishment of a cooperative framework for social policy in the European Union (EU).

The passage of the “Single European Act” (SEA) in 1986 marked the beginning of an institutional change in the EU’s treatment of social issues and policies. The Amsterdam Treaty

(enacted in 1999) formalized the idea of the ‘European Employment Strategy’ an instrument to reform European labor markets. Such changes reached their climax at the Lisbon European

Council in March 2000, which established a ten-year strategy to reach 70 percent employment rate. The main task behind creating a set of employment guidelines is to boost employment in the

European Union by 2010 with the end of making Europe the most competitive market in the world. In addition, the Lisbon European Council launched the ‘Open Method of Coordination’

(OMC), a new regulatory model for developing ‘Social Europe’ that is not legally binding and is voluntary in nature. The method was designed to assist member States to develop their own social policies, and help in spreading best practice and achieving greater convergence towards the main EU goals. (Interview, Directorate General of Employment and Social Affairs).

Many have argued that the creation of a common European framework on the area of employment policy could influence and/or transform existing domestic legislation, policies, politics, and administrative structures. For example, European member States may have to create and/or restructure existing institutions, processes, policies and/or legislation to fit EU standards and goals. The aim of this paper is to explore how European

1

pressures on the employment policy area have affected the member States’ processes, institutional configurations, policies and actors.

2

This paper will present preliminary data collected in Spain and Belgium to illustrate the effect of the EES at the national level. Moreover, the ultimate goal of this research project is to explain ´ why, how and when` the EES affects national policies, processes, and institutional configurations.

In the next section, I describe the creation and formation of the European Employment

Strategy at the European level. I then proceed to explain how can we understand the effect of the

1 From now on, I will use the concept ‘European’ to refer to the supranational level, the European Union.

2 This research project studies three cases—Spain, Sweden and Belgium. Moreover, the data presented is still preliminary.

2

European Employment Strategy at the national level. Next, I present the data gathered in

Belgium and Spain. I end with a discussion of the findings presented.

II) Background

After the passing of the Single European Act (1986) the discussion about the social ambit of the EU grew steadily. Issues such as gender equality in the workplace, health and safety of workers, and employment policy became part of the EU agenda because they were considered important elements of a successful and strong Single Market program. The 1991 December summit of the European Community (EC) at Maastricht, Netherlands resulted in a number of institutional changes. The most striking change was the commitment to an economic and monetary union (EMU). In addition, eleven of twelve members also agreed to a “Social

Protocol.” This agreement contains provisions on direct cooperation between social partners and the EU on issues concerning employers and trade unions. The Treaty of Amsterdam restated the necessity of adopting “directives laying down minimum requirements in the social field and measures designed to encourage cooperation between Member States [and the] adoption of measures concerning social security and social protection of workers” (Treaty of Amsterdam,

Article 137(2), ex Article 118). In addition, this treaty included an Employment Chapter (Art.

125-130). This Chapter stated that the EU and member States should consider employment policy “as a matter of common concern.” The Amsterdam treaty and the Employment Summit in

Luxembourg (1997) developed an annual procedure to guide an institutional framework to make member States accountable to the EU on employment matters.

3

These innovations reached a climax at the Lisbon European Council (March 2000). The

Summit set a new strategic goal—“to become the most competitive and dynamic knowledgebased economy in the world capable of sustainable economy growth with more and better jobs and greater social cohesion.” (Conclusion of the Portuguese Presidency). It gave the ‘European

3 The process is the following. The Commission drafts a set Employment guideline that is voted upon by the

Council (decision rule--QMV). An advisory body, the ‘Employment Committee’ (EMCO), was set up. This body consists of two officials from each member state and two Commission officials. During the process of drafting social partners, the European Parliament, the Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions are consulted. Based on the guidelines the member States need to create National Action Plans on Employment

(NAP’s). Then member States submit NAP’s to the Commission for cross-national comparison and evaluation.

Meanwhile, member states are reviewing each other’s plans at EMCO. Then a report is created. It compares practices, establishes benchmarks, and best practices. In addition, the Council makes recommendations to member

States about their practices (QMV).

3

Employment Strategy’ (EES) new impetus by creating a ten-year plan (from 2000 until 2010) to reach 70% employment rate. An important feature of this process is that it implies a new system of governance in the EU—the ‘Open Method of Coordination’ (OMC). The OMC is different from traditional regulation in that it proposes general standards instead of detailed rules. For example, Mosher (2000) conceptualizes this new method as a “a post-regulatory approach to governance.” Under the OMC, member States have the option to implement (or not) European employment standards, and the country decides how she will be implementing EU standards.

Therefore, it allows for greater flexibility, variation, and voluntarism than other EU regulatory instruments (directives and regulations).

The OMC should be understood within one of the most important principles of the EU— subsidiarity. When we refer to social policy, specifically to employment policy

4

, the notion that

‘subsidiarity reigns’ is shared by many scholars. (Hix,1999; Peters, 1992; Schaefer, 1991).

Subsidiarity refers to the principle that “all actions in social and political life should be performed by the smallest possible unit. […] This approach would mean that the EC

“government” would do as little as possible, leaving most functions to the national and, perhaps especially, subnational governments” (Peters, p.110). Subsidiarity implies a bottom-up approach in which the lowest unit will be empowered with the responsibility of performing a task.

Applying the principle of subsidiarity to discussions about social policy and OMC presumes: a) that the national and/or regional governments (within the member State) would be responsible for managing social issues and benefits (such as the management of employment policy, taxing, and redistribution in the form of welfare programs) not the European Union; and b) the EU will limit its role to one of guide to members States on the process of policy-making and implementation, because under OMC this supranational entity does not have the legal instruments to act as an enforcer.

Moreover, to understand the growing emphasis on employment policy by the Union we must not limit the analysis to the ‘social dimension,’ but we need to refer to the ‘economic’ ambit of the EU--the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). The creation and development of the Monetary Union caused great externalities on the area of employment policy because the

4

Roberts and Springer (2001) comment that employment policy has been a close relative of social policy, and that these terms have been used interchangeably throughout much of EU’s history. The authors argue, “employment policy and social policy coexist with only an unclear border between them, but employment policy is the star of the era and the one that attracts the broadest support” (Roberts and Springer, 2001, p. 27).

4

range of available policy options, especially in the macro-economic field, to members of the

EMU are limited and restricted. Thus, it could be argued that the EMU constrains the national context of employment policy in numerous ways. For example, Goetschy (forthcoming) argues that traditional job creation policies became obsolete because,

1)It was no longer possible to foster employment by means of competitive devaluation and adjustment of national rates because EMU entailed an increasingly centralized monetary policy for the EU; 2) EMU and the adoption of the Stability Pact (1997) prohibited large public deficits and hence attempts to combat unemployment by means of public-sector job creation; 3) Community competition law began to weigh upon employment by increasingly limiting certain types of state aid to undertakings in specific sectors and by granting or withholding permission for mergers and takeovers by major industrial or financial groups. (Goetschy, 62)

In sum, EU social policy, specifically employment policy, could be considered part of the Western European social discourse. Nevertheless, we should not forget that the inclusion of employment policy at the EU level is one of the multiple pieces that hold the economic and monetary program together.

III) Employment Policy and the National Level

In the last decade scholars, lawyers and policy-makers have shown considerable interest in the new treaty provisions, social developments, and their consequences on the development of the supranational entity. Scholars ignored until very recently the growing impact of ‘Europe’ at the national and the sub-national level scholars. Most studies on the European Union used a

‘bottom-up’ approach that focused on supranational processes, such as the transfer of competencies from the national to the supranational level, institution building, and decisionmaking in Brussels. Moreover, scholars began to expand the field by studying and theorizing

‘Europeanization’ (Börzel, 2002; Falkner, Hartlapp, Leiber and Treib, 2002; Cowles, Carporaso, and Risse, 2001; Héritier et al, 2001). The “next phase” of European integration studies focused on ‘why, how, when, and at what degree’ Europe matters at the national and the sub-national level.

Nowadays, there is little controversy about the idea that European processes affect domestic politics. Authors have developed this ‘top-down’ perspective by arguing that European integration and Europeanization affect the domestic structures of European member States. The authors seem to agree that Europe matters in different countries in different ways. To illustrate

5

their argument they have studied the national implementation of European policy measures ruled by hard-laws (directives and regulations).

The authors presented above (Börzel, 2002; Falkner, Hartlapp, Leiber and Treib, 2002;

Cowles, Carporaso, and Risse, 2001; Héritier et al, 2001) explore the notion of ‘misfit’ to understand how and when member States would implement European directives and regulations.

These works share one point-- they interpret instances in which European inputs are legally binding (hard law). The notion of ‘goodness of fit’ is grounded on the assumption that national legislation must change when the EU launches regulations or directives because these instruments are legally binding. Under this circumstance, member States are knowledgeable of the legal instrument, and they are aware they should comply with these European regulations and directives. In addition, EU institutions provide the legal instruments (infringements and litigations) to threat and punish member States that do not comply with these regulations. Thus,

European institutions, specially the Commission and the Court of Justice, act as enforcers.

However, the concepts of ‘misfit’ and ‘fit’ weaken when we refer to non-legally binding and voluntary mechanisms used by the European Union, such as the OMC. First, under OMC states are not obliged to change their national legislation to comply with EU regulations because compliance is voluntary. Second, given that European inputs are a set of guidelines (not EU regulations and directives that involves a formal European legislative process), under OMC the measurement for domestic outcome is not limited to a change of legislation.

5

Under this new method the adoption of new legislation to fit European directives is not a requisite for implementation. Thus, contrary to policy areas ruled by hard law, under OMC legislative fit to

European directives is not a sufficient, nor a necessary condition for reform/implementation.

This means that under OMC countries might experience reform even if current legislation does not fit European standards. Third, the EU cannot legally threaten or punish member States if they do not comply with non-legally binding European initiatives, such as the ‘European

Employment Strategy.’ Thus, EU’s role as an enforcer loses power. Consequently, I claim that we must understand how soft governance tools and instruments affect the domestic institutions, processes, actors, and policies. We need to comprehend how non-binding directives affects

5 The misfit literature measures outcomes as changes of national and/or sub-national legislation. Thus, it looks at how national/sub-national legislation fits (or does not fit) European legislation (in the form of regulations and directives).

6

member States so we can develop a theoretical model that explains these instances and that can be applied to other policy areas ruled by voluntarism.

Five- years have passed since the introduction of the EES. If this strategy has been successful, in any way, it could be argued that it has had some type of impact at the national and/or sub-national level. For example, De la Porte and Pochet (2002) contend that in some countries the EES has affected the national distribution of power.

6 Thus, it could be argued that member States are experiencing changes and reforms related to EU inputs and forces.

7

Preliminary gathered data shows that the EES has already influence certain national processes and institutions.

IV) Assessment of how the European Employment Strategy Has Affected Member States

In this section of the paper, I will present preliminary data gathered in Spain and

Belgium to explore how the EES has affected member States´ actors, institutions and processes.

8

A) Raising Awareness about Employment Policy

After the Treaty of Amsterdam, ‘employment’ became one of the major concerns of the

European Union. Governments became more aware about the importance of employment policy, and were more willing to pay attention to it. Consequently, employment policy became part of the agenda in scenarios that were not traditionally linked to this type of policy. A policy-maker at the Spanish Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs stated, “After the Treaty of Amsterdam employment policy was placed at the center of all European policies and that, in some way or another, has led some ministries that were not involved in employment policy (because they thought their actions did not have any impact on it) to get involved in it. Now the majority of the policies (in the public ambit), their consequences are measured, or are taken into consideration, to see how they will affect employment. […] And that has make all the organizations, in the public and the private sphere, aware that their actions will affect the job market in the country.”

6 For example, Jacobsson (2002) claims that Swedish employers returned to joint dialogue after a period of nonparticipation.

7 Refer to Pochet and de La Porte (2002) for the Swedish, Spanish and French cases. Moreover, refer to Jacobson

(2001) for a description of the Swedish case.

8 For this study, I have chosen to conduct in depth case studies using intensive semi-structured interviews and document analysis. Moreover, the research project employs a comparative research design to identify general patterns, causal relationships and correlations, and cross-national similarities and variations.

7

(Interview, 2003).

9

The former quotation illustrates how in member States, such as Spain, employment policy became an influential part of the national agenda. This is significant in the way the EES has the capacity of shifting the focus of the policy-making agenda at the national level. In addition, employment policy did not only form part of traditionally scenarios (for example, Labor Ministries and public organizations), but was included in unconventional ones

(for example, private organizations).

B) Employment policy and policy-making

The European Employment Strategy (EES) requires that national governments (ministers,

Secretaries, and their staff), social partners (employers’ organizations and trade unions) and other organizations/actors (for example, the Autonomous Communities in Spain, and the Communities and the Regions in Belgium) meet every year to create and draft the National Action Plan on

Employment (NAP). Then, it is submitted to the European Union for revision. The document describes member states` employment policies and programs. Moreover, the NAP’s explain the measures and actions taken by member States to comply with EU employment guidelines and recommendations.

This iterative process has had an impact on national processes and actors. Interviewed national actors seem to agree that the EES has added cohesion, structure, clearness and cohesiveness to their national policies and policy-making processes. Now, they argue, policy makers and national authorities dealing with employment are talking more to each other than before, and are trying to work together on common matters related draft to employment. This is entails more communication, cooperation, and coordination between the involved parties.

Many would take for granted the idea that governments have a clear and concise idea about their policies and administrative structures. However, this has not been always the case in

Belgium and Spain. The fact that after 1997 (Luxembourg Summit) different national entities get together to discuss their employment strategies and policies and to draft the NAP’s imposes some level of structure and clearness to the process of policy-making. The following quote illustrates this point, “The process of drafting the NAP´s allow us to be aware of the actions taken by different ministries and different general organizations, they could be autonomic, even

9 In Belgium, the interviews were conducted in English. Moreover, the presented citations were not edited. In

Spain, the interviews were conducted in Spanish. Thus, the citations were translated from Spanish to English.

8

local (town councils), to be able to see the coherence and the incoherencies of the different actions, or, if there is an overlapping between some of them […] then the government would be able to reconcile or add coherence to their policies” (Interview, 2003).

10

The impact of the EES has not been limited to how policies are organized, but ‘how policy making happens’. The annual procedure forces member States to assess the effect of policies related to employment. This process may seem natural to many organizations (policy is created, implemented, and after a while its effect is evaluated). However, that has not been the case in all member States. The EES forces states to evaluate the effect of the policies related to employment. A policy maker at the Belgian Ministry of Labor said without any hesitation,

One of the key elements of the EES is that it focuses on results. So, it is about ‘you have to obtain this or that level of employment’, etc., and ‘we are for results’. That is the reason there are so many indicators, just to measure results. And traditionally the policy debate, especially on employment, in Belgium was not much about results, but about measures. “What measures should we develop?, and how can we agree.” [...] There was not a culture of evaluation. And, that is a kind of political change. By objectifying these, it is difficult for Belgium because it is new. [...] But, that is another way of looking at policy. The idea of having to raise the employment rate it was not in the Belgian mind, before the strategy and before Lisbon. [...] But, I remember because I lived in the ‘80’s, and they were trying a lot of things to decrease unemployment. So, there was no time for this type of long-term view. Everyone was under pressure. And some of these measures were better than others, and that was the problem that we had no time to stop and think about it. Now it is a different way. Now you have to meet and talk about it, and that is a new way of thinking. (Interview, 2002).

The quote above raises several points about the influence of the EES on domestic processes. First, the EES affects the ‘how policy happens’ at the national level. These policy makers point out that in Belgium “there was not a culture of evaluation.” Thus, the processes attached to the EES compel states to assess the impact of certain policies. Second, this “culture of evaluation” represents a “political change” to this Belgian policy maker. These public servants are pointing out that the change is not a minor one because it shakes the political structures of this country. The findings illustrate how the EES makes member States reconsider the processes that have been strongly ingrained in their way of making policy--a process that is vital to any polity. At the same time, this statement resonates with the arguments exposed by the

‘Historical Institutionalist’ literature about path-dependency. If we envision national policy

10 It refers to the Confederation of Spanish Employers.

9

making as an institution, then it could be argued that the EES is an emerging institution that shifts the current path of ‘how policy happens’ at the national level.

11

C) “It is necessary because Europe said so”

1. Peer-pressure

The EES process of revision (EU´s recommendations and the annual presentation of NAP´s) seem to affect the choices that governments make in terms of which policies should be brought to table, and which ones should be further developed. The process of revision provides member

States with information, ideas and ‘problem solving strategies’. Every member State always has a ‘transnational reference´ on how to solve a problem. This means that she will always have the option to look into ‘what works or does not work’ on their peers’ countries, and she may test or discard all sort of ‘imported problem solving strategies’. In addition, national governments could be ‘forced’ to adopt certain strategies because other member States are ‘watching’ their actions and procedures. Thus, peer-pressure plays a big role on the strategies and solutions adopted by a country to solve or diminish the effect of a problem.

12

2. Introduction of an Agenda, and Legitimization of Actions.

It appears that the process attached to the EES influences national actors to develop policies that otherwise would not have been expanded because of lack of commitment between actors and/or because of their complex nature. The process makes member States aware that policy ‘X’ is necessary at the national level because it is essential to achieve economic and social prosperity, for instance. For example, representatives of one of the Spanish trade unions claimed that the EES made “gender equality in the workplace” a salient issue in Spain. Before the introduction of the EES, they said, there was a lack of commitment on the issue--neither government nor CEOE (employer organization) were attacking the problem. Thus, the EES, specifically, its fourth pillar (equal opportunities), compelled social partners to include the issue of gender equality on their 2002 and 2003 “Acuerdo para la Negociacion Colectiva” (Agreement

11 Examples of this type of work are: Steunenberg and van Vaught (1997); Steinmo, Thelen, and Longstreth (1992);

Hall (1986); Rueschemeyer and Skocpol (1996). In addition, refer to Pollack (mimeo).

12 The process of revision spreads the message that a country is falling behind given that the document includes quantitative indicators.

10

on Collective Negotiation).

13

In this way, the EES has the capacity of increasing instances of successful cooperation between national actors on issues that otherwise they would not be involved with.

Additionally, “Europe’s presence” at the national level could be legitimizing national actors’ actions in the eyes of other domestic parties and/or of the public. Thus, the government and/or social partners could refer to ‘Europe’ when they want to take an action that otherwise would not be approved by other involved parties and/or the public . For example, a Spanish policy- maker stated, “One of the big arguments that the government was making was that the guidelines mentioned that changes were necessary. That, definitively, supposes a big impulse. […] and that

[the EES, my clarification] reinforces [government’s actions, my clarification] on the public eye… and on trade unions` eyes. And, then, the recommendations [provided by the European

Unions, my clarification] to the government telling them, “you have fiscal impositions on jobs, and you have not reduced it,” that is decisive.” (Interview, 2003).

In sum, the ‘pressure from Europe’ might increase the level of successful cooperation between national actors. It seems that the process influences national actors to develop policies that otherwise would not have been expanded because of lack of commitment between actors/organizations, and/or because of their complex nature. Moreover, governments and domestic actors could use the EES (‘we did it because Europe says it is good’) as an excuse to legitimize their actions.

D) A New Arena for Negotiation?

The EES promotes national social dialogue between social partners and the government.

14

The process encourages social partners and governments to cooperate and work together on the drafting and implementation of the NAP´s.

15

Thus, we could argue that the ESS opens a window of opportunity for trade unions, employer organizations, and the government because it creates a

13

On the same vein, interviewed Belgian policy-makers argued that “late retirement” became an issue because the

EES points at the necessity of prolonging workers` working age because of the European demographic crisis. Thus, this European input is modifying existing policies and discourses about early retirement.

14 For example, the European trade union (ETUC) and European employers organizations (UNICE and CEEP) are included in the consultation process at the supranational level.

15 The Lisbon Strategy recognizes that full employment and social cohesion depends on considerable extent ion the action of social partners at all levels, including the drafting of NAP´s. For an overview of the Commission’s position about social partners refer to “The European social dialogue, a force for innovation and change, ” COM

(2002) 341 final, 2002/0136 (CNS), 26.6.2002.

11

new bargaining scenario . However, is this the case? The preliminary gathered data shows that social partners have been included in the process. In Spain, social partners have not formed part of the process at every stage. In this country, the government drafts the NAP, and then trade unions and employer organizations revise the document and provide suggestions.

16

In Belgium, social partners are consulted at different stages because they are institutionalized into many governmental structures.

Moreover, it seems that social partners are not very satisfied with their involvement in the process. Mostly they claim that the government does not acknowledges their claims and/or that the government does not include them at every stage of the process (Spain). However, this level of dissatisfaction does not truly disappoints them. The social partners recognize that: a) even if they are not taken into account, the government must consult them at another stage of policy-making. For example, on many occasions they are in charge of implementing certain policies. Thus, at the end, their participation is guaranteed through other established fora and institutions. b) the role of the government is to govern.. Thus, it is responsible for creating policies and the structures necessary for making them tangible.

In sum, the question-- does the EES creates a new arena for negotiation?, it is still on the table. I am inclined to argue that it does represents a new arena of influence (for example, the inclusion of gender equality in Spain). However, social partners do not consider the added value of these fora because they cannot represent its clients as they would want to. In addition, I would argue that social partners do not perceive that a new arena for negotiation is created given that they are already consulted on multiple matters and scenarios.

E) Change of Legislation

As it has been pointed above, the process accompanying the EES could influence national entities to take actions that otherwise they would not take because of the complexities attached to the process. The EES could shape and reinforce existing ideas (at the national level), converting them into tangible policies, and in some occasions, laws. This is the case of the “Ley de

Cualificaciones y de la Formacion Profesional” 17

(law 5/2002) that visibly responds to the first

16 In Spain, the suggestions are included as an annex. Thus, the government does not change the content of the document after it has been submitted to the social partners.

17 Refers to the Law for Qualifications and Professional Training.

12

pillar (employability) of the European Employment Strategy.

This pillar is centered on the idea of lifelong learning. The information gathered points out that in Spain lifelong learning is not a new concept.

18

For example, a Spanish policy- maker argued that for about ten years the concept of lifelong learning has been part of the documents related to training. With the introduction of the EES, and later on with the agreement signed by the social partners, 19 the concept of lifelong learning materialized into a law project in Spain. The interviewed policy-makers stated, “We have been talking about lifelong learning for many years, and if we look at the documents related to training for ten years the general message has not been very different. The practical effects and the concrete implications… maybe those change throughout time. Then, it is true that

Europe increases the power of this approach, and there are more concrete objectives related to this. A reflection of this, the most important we consider, is this law. […] So, in the last couple of years there has been a progress, and this law fits with other European projects and tendencies.” (Interview, 2003). The quote illustrates how the European forces strengthened the discourse of lifelong learning to the point that it became a law.

20

V) Conclusion

In the section above, I have attempted to illustrate how the European Employment

Strategy has affected national processes and configurations. How are these findings significant?

First, this project attempts to contribute to the ´top-down’ perspective of Europeanization by including social policy on the agenda. Second, these findings fit within the literature that studies the process of Europeanization of domestic structures because they illustrate how European pressures related to employment policy: 1) shape many processes (specially policy-making processes), 2) affects the behavior of national actors and, 3)restructures national structures.

18 Interviewed policy makers in Spain and Belgium pointed out that the OECD has been using the concept of lifelong learning for decades.

19 On February 2002, the European social partners (European Trade Union Confederation, Union of Industrial and

Employer’s Confederation of Europe, and European Center of Enterprises with Public Participation and of

Enterprises of General Economic Interest) reached an agreement (non-binding in nature) in which they recognize the importance of lifelong learning.

The agreement also states that the signatories will draw up an annual report on the national actions carried out based on their priorities. After the drafting of three annual reports, the partners will evaluate the impact of this exercise on employers and employees, which may lead to the updating of the priorities.

The ad hoc group on education and training will present this evaluation in March 2006.

20 It must be clear that I am not claiming that the EES caused the creation of the law. However, I do claim that we should not deny that there is a strong relationship between the first pillar of the EES and the process of creation of the law.

13

Moreover, it adds a new dimension to the debate about the Europeanization of domestic structures by focusing on non-binding (voluntary) measures created by the European Union. My approach not only considers change in legislation (as the obvious outcomes), but looks into the processes of change and reform of domestic structures and processes. Thus, it acknowledges that the effects of the EES at the national level could take different forms that include—no reform, policy change, reform of policy-making processes, and change in the power distribution of domestic actors and/or organizations. These insights are especially relevant if we consider the prospects of enlargement in European Union.

The former argument brings us to a second point—the importance of studying the effect of European soft-governance tools. The findings presented on this paper tell us that we should not underestimate the effect of non-binding measures on national settings. First, we see that the

EES not only has affected the behavior and rules of procedure of national actors, but it also shapes ‘tangible’ structures, such as laws. Second, the data show that national actors are compelled to act in certain ways to comply with the EES even when there are no legal threats attached to the process. Actors involved in the policy-making process may adopt certain strategies and actions for the sake of being competitive or/and for the well being of its country, for example.

Finally, we must allude to the question—are European employment policies converging because of the EES? I would have to say that the answer to the former question is negative.

Something that has become very clear is that member States still have, and will have, competence over their employment policy. European member States do not wish to grant any power to the European Union on this matter. Therefore, there could be no convergence.

However, we could talk about a common point of reference (EES) that dictates what constitutes a proper and desirable policy, and a set of standard procedures. In this sense, member States may experience some level of convergence.

14

Bibliography

Andersen, Svein S and Kjell A Eliassen.1993. Making Policy in Europe: The Europeification of National Policymaking , London: Sage Publications.

Arcq, Etinee and Pochet, Phillipe. 2000. ‘UNICE and CEEP in 1999: social policy perspectives’ in Emilio Gabaglio and Reiner Hoofman (ed.), European Union Yearbook 1999, Brussels: ETUI.

Ardy, Brian and Begg, Iain. 2001. “The European Employment Strategy: Policy Integration by the Back-Door?,”

Paper presented for the European Community Studies Association 7 th Biennial International Conference, Madison:

Wisconsin.

Börzel, Tanja A. Forthcoming. Environmental Leaders and Laggards in the European Union, London: Ashgate

_________ 2002. States and Regions in the European Union: Institutional Adaptation in Germany and Spain,

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

__________ .2001. ‘Non-compliance in the European Union: pathology or statistical artifact?’, Journal of European

Public Policy , vol. 8, no. 5, pp. 803-824.

Börzel, Tanja and Thomas Risse. Forthcoming. “Conceptualizing the Domestic Impact of Europe,” Presented at the 2001 ECPR Summer Institute, Leiden University, The Netherlands.

Burrows, Noreen and Jane Mair. 1996. European Social Law, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons.

Collins, Doreen. 1975. The European Communities: The Social Policy in the First Phase, Volume 1 The European

Coal and Steel Community 1951-1970, London: Martin Robertson.

Commission of the European Communities “The European social dialogue, a force for innovation and change, ”

COM (2002) 341 final, 2002/0136 (CNS), 26.6.2002, http://europa.eu.int/eurlex/en/com/pdf/2002/com2002_0341en01.pdf

Commission of the European Communities. 2000. COM europa.eu.int/comm/employment_social/general/com00-

379/com379_en.pdf.

Cowles, Maria Green, James Carporaso, and Thomas Risse. 2001. Transforming Europe: Europeanization and

Domestic Change, New York: Cornell University Press.

Cram, Laura.1994. ‘The European Commission as multi-organization: social policy and IT policy in the EU’,

Journal of Public Policy , Vol.1, No. 2.

De la Porte, Caroline, ‘The Novelty of the Place of Social Protection in the European Agenda in 1999 through “Soft

Law”’ , mimeo (Brussels: Social Observatoire)

De la Porte, Caroline and Phillipe Pochet. 2002. Building Social Europe through the Open Method of Co-ordination,

Brussels: Peter Lang.

Directorate General for Education and Culture. 2001. National Actions to Implement Lifelong Learning in Europe,

Belgium: CEDEFOP and EURYDICE.

Esping-Andersen Gøsta. 1990. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

European Commission, Directorate-General for Employment. 2002. Employment in Europe: Recent Trends and

Prospects, Brussels: EURES.

15

European Commission and Employment and Social Affairs.1999. Forum Special: 5 Years of Social Policy,

Belgium: European Commission.

European Communities. 1999. European Union: Selected Instruments taken from the Treaties , Madrid: Office for

Official Publications of the European Communities.

European Union on- Line. 1999. Presidency Conclusions, europa.eu.int/council/off/conclu/june99/june99_en.htm.

Hall, Peter A. and David Soskice. 2001. Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative

Advantage, New York: Oxford University Press.

Hix, Simon. 1999.

The Political System of the European Union , Great Britain: Palgrave.

De la Porte, Caroline and Phillipe Pochet. 2002. Building Social Europe through the Open Method of Co-ordination,

Brussels: Peter Lang.

Deacon, Bob. 1999. ‘ Socially Responsible Globalization: A Challenge for the European Union,’ mimeo, Finland:

Globalism and Social Programme.

Dinan, Desmond. 1999. Ever Closer Union , Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Esping-Andersen, Gøsta. 1990. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

European Commission. 2002. Recommendation on the Implementation of Member States’ Employment Policy, http://europa.eu.int/comm/employment_social/empl&esf/news/emplpack2001_en.htm#Employment.

Falkner, Gerda, Miriam Hartlapp, Simone Leiber, and Olivers Treib. “Transforming Social Policy in Europe? The

EC's Parental Leave Directive and Misfit in the 15 Member States.” Presented at the 13th International Conference of Europeanists "Europe in the New Millenium: Enlarging, Experimenting, Evolving", Chicago, 2002-03-14/16.

Goetschy, Janine.

Forthcoming 2003. "The European Employment Strategy, Multi-Level Governance, and

Policy Coordination.", in: Jonathan Zeitlin and David Trubek, (eds)., Governing Work and Welfare in a

New Economy: European and American Experiments . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

____________.

Forthcoming 2002. "2001-2002: Transition Years for Employment in Europe: EU

Governance and National Diversity under Scrutiny."" Industrial Relations Journal 33(5).

Hall, Peter. 1986. Governing the Economy: The Politics of State Intervention in Britain and France, Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Hantrais, Linda. 2000. Social Policy in the European Union , United States: St. Martin’s Press.

Hay, Colin. 2001. Globalisation, Competitiveness and the Future of the Welfare State in Europe,’ Paper Presented for the European Community Studies Association 7 th Biennial International Conference, Madison: Wisconsin.

Hemerijk, A, Unger, B., and Viser J. 2000. ‘Austria, the Netherlands, and Belgium’ in Fritz W. Scharpf and Vivien

A. Schmidt (ed.) in Welfare and Work in the Open Economy: From Vulnerability to Competitiveness, Oxford:

Oxford University Press.

Héritier, Adrienne, Dieter Krewer, Christopher Knill, Dirk Lehmkuhl, Michael Teutsch, and Anne-Cecile Douillet.

2001, Differential Europe: The European Union Impact on National Policymaking , Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield

Publishers.

16

Jacobson, Kerstin. Forthcoming, 2002. "Soft Regulation and the Subtle Transformation of States: The

Case of EU Employment Policy." In: Bengt Jacobsson & Kerstin Sahlin-Andersson, eds., Transnational

Regulation and the Transformation of States .

Kassim, Hussein, B. Guy Peters, and Vincent Wright. 2000. The National Co-ordination of EU Policy , Oxford:

Oxford University Press.

Kerremas, Bart. 2000. ‘Belgium’ in Peters Guy and V.Wright (ed.) The National Co-ordiation of EU Policy: The

Domestic Level, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kuhnle, Stein. 2000. ‘The Scandinavian Welfare State in the 1990s: Challenged but Viable’ in Maurizio Ferrera and

Martin Rhodes (ed.) Recasting the European Welfare State, London: Frank Cass.

Leibfried, Stephan, and Pierson, Paul. 2000. ‘Social Policy: Left to Courts and Markets?’ in H. Wallace and W.

Wallace (ed.) Policy-Making in the European Union, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

______________1995. European Social Policy: Between Fragmentation and Integration, Washington: The

Brooking Institution.

Lin, Ann Chih. 2000. Reform in the Making: The Implementation of Social Policy in Prison , New Jersey: Princeton

University Press.

Martin, Lisa A. 2000. Democratic Commitments: Legislature and International Cooperation, Princeton: Princeton

University Press.

Mendriou, Maria. 1996. ‘Non-Compliance and the European Commission’s Role in Integration’, Journal of

European Public Policy , Vol. 3, No. 1.

Mény Yves, Pierre Muller and Jen-Louis Quermonne. 1996. Adjusting to Europe: The Impact of the European

Union on national institutions and policies, London: Routledge.

Molina, Ignacio. 2000. ‘Spain ,’ in H. Kassim, B.G. Peters and V. Wright (ed.), The National Co-ordination of EU

Policy: The Domestic Level, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Moravcsik, Andrew. 1997. ‘Taking Preferences Seriously: A Liberal Theory of International Politics’, International

Organization, Vol. 51, Autumn 1997, pp. 513-553.

_______________ .1998. The Choice for Europe: Social Purposes & State Power from Messina to Maastricht ,

New York: Cornell University Press.

Mosher, James.2000. "The Open Method of Coordination: Functional and Political Origins." ECSA Review 13(3):

6-7.

Pacolet, Jozef. 1996. Social Protection and the European Economic and Monetary Union , England: Avebury.

Pakaslahti, J.1997. ‘Does EMU Threaten European Welfare: Social and Political Implications of Its Transitional

Stage in EU Members’, Working Paper, Nr. 17, Brussels: European Social Observatoire.

Peters, B.G. 1992. ‘Bureaucratic Politics and the Institutions of the European Community’, in A.M. Sbragia (ed.),

Euro-Politics: Institutions of the European Community in the “New” Europe, Washington DC: The Brookings

Institution.

Pierson, Paul. 2001. The New Politics of the Welfare State, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pollack, Mark. A., ‘The New Institutionalism, Hypothesis-Testing, and Questions of Methods’, mimeo,

Workshop on Institutionalism in the Study of the European Union.

17

Pontusson, Jonas. 1997. “Between Neo-Liberalism and the German Model: Swedish Capitalism in Transition,’ in

Political Economy of Modern Capitalism, ed. Colin Crouch and Wolfgang Streeck, California: Sage.

_________ and Peter Swenson. 1996. ‘Labor Markets, Production Strategies, and Wage Bargaining Institutions: The

Swedish Employer Offensive in Comparative Perspective,’ Comparative Political Studies 29 (April): 223-50.

Roberts, Ivor, and Beverly Springer. 2001. Social Policy in the European Union: Between Harmonization and

National Autonomy, Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Rhodes M.1996. ‘Globalisation and West European Welfare States: a critical review of recent debates’, Journal of

European Social Policy , Vol. 6, No. 4, pp. 305-327.

Royo, Sebastián. 2002. ‘A New Century of Liberal Corporatism in Iberia?,’ Paper delivered at the Thirteen

International Conference of Europeanists (Chicago, March 14, 2002).

____________. 2000. From Social Democracy to Neoliberalism: The Consequences of Party Hegemony in Spain,

1982-1996 , United States: St. Martin Press.

Rueschemeyer, Dietrich and Theda Skocpol. 1996. States, Social Knowledge and the Origins of Modern Social

Policies, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Schaefer, Gunther F. 1991. ‘Institutional Choices: the rise and fall of subsidiarity’, Futures .

Scharpf, Fritz W., and Schmidt, Vivien. 2000. Welfare and Work in the Open Economy: From Vulnerability to

Competitiveness , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Steinmo, Sven, Thelen, Kathleen and Longstreth, Frank. 1992. Structuring Politics: Historical Institutionalism in

Comparative Analysis, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stone Sweet, Alec and Brunell L., Thomas (1999) Alec Stone Sweet and Thomas L. Brunell Data Set on Preliminary

References in EC Law ( Robert Schuman Centre, European University Institute: Italy).

Swedish Government (Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Industry, Employment and Communication). 2002.

Sweden’s Action Plan for Employment, 2002.

_____________. 2001. Sweden’s Action Plan for Employment, 2001.

_____________. 2000. Sweden’s Action Plan for Employment, 2000.

Tallberg, Jonas and Jonsson, Christer. 2001. ‘Compliance Bargaining in the European Union’, Paper Presented for the European Community Studies Association 7 th Biennial International Conference, Madison: Wisconsin.

Teague, Paul. 1994.

‘Between New Keynesianism and deregulation employment policy in the European Union,’

Journal of Public Policy, Vol. 1, No. 3.

The European Convention. 28 October 2002.

‘Preliminary Draft Constitutional Treaty,’

Cone. 369/02, Brussels.

Tsebelis, George. 2002. Veto Players: How Political Institutions Work, Princeton : Princeton University Press.

______________.1995.

‘Decision Making in Political Systems. Veto Players in Presidentialism, Parliamentarism,

Multicameralism and Multipartidism,’ British Jouranl of Political Science, Vol. 25, No. 3.

18