A VOLUNTEER MODEL AND CASA Dianah Lynn Lewis

A VOLUNTEER MODEL AND CASA

Dianah Lynn Lewis

B.S., California State University, Sacramento, 1990

THESIS

Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of

MASTER OF ARTS in

PSYCHOLOGY

(Counseling Psychology) at

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, SACRAMENTO

FALL

2010

A VOLUNTEER MODEL AND CASA

A Thesis by

Dianah Lynn Lewis

Approved by:

_______________________________, Committee Chair

Dr. Marya Endriga

_______________________________, Second Reader

Dr. Becky Penrod

_______________________________, Third Reader

Dr. Rebecca Cameron

_______________________________

Date ii

Student: Dianah Lynn Lewis

I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this thesis is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for this thesis.

______________________________, Graduate Coordinator

Dr. Jianjian Qin

Department of Psychology

_________________

Date iii

Abstract of

A VOLUNTEER MODEL AND CASA by

Dianah Lynn Lewis

This research is an attempt to operationalize and test some of the concepts in a new model for volunteerism. Of specific interest was change in scores for empowerment, compassion satisfaction, and burnout based on volunteer length of service. Volunteers from the non-profit organization, Court Appointed Special Advocates (CASA) of

Placerville, California, completed the Professional Quality of Life (ProQOL) and

Menon’s Empowerment scale. CASA administrators supplied information about eighteen months of volunteer retirements including start and end dates of service. Empowerment, especially the components of perceived control and perceived competency were significantly lower in groups with 9 to 18 months of volunteering experience compared with groups with 0 to 8 months. Compassion satisfaction also declined between groups but only approached significance. No significant differences were found with the burnout measure. Only some of the model was supported, additional studies are needed.

_________________________________, Committee Chair

Dr. Marya Endriga

_________________________________

Date iv

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Chapter

The Role of Efficacy in Continued Volunteerism. ..................................... 9

ProQOL: Compassion Satisfaction and Fatigue ....................................... 14

Court Appointed Special Advocates ......................................................... 16

Purpose of the Current Study and Hypotheses ......................................... 19

2. RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS ................................................................. 20

Archival CASA Exit Data ......................................................................... 20

The Professional Quality of Life Scale (ProQOL) ................................... 23

Archival CASA Exit Data ......................................................................... 26

Analysis of Questions Asked by CASA Administrators .......................... 34

First Year Compared to Second Year Analysis ........................................ 41

Post Hoc Information Analysis ................................................................. 48

Study Limitation and Applications ........................................................... 51

vi

3.

4.

5.

1.

2.

8.

9.

6.

7.

LIST OF TABLES

Table 2 Analysis of Variance for Empowerment x Length of Service ................. 31

Table 3 Analysis of Variance for ProQOL x Length of Service........................... 33

Table 4 Descriptive Statistics for CASA Questions ............................................. 35

Table 6 Correlations for CASA Questions and Empowerment ............................ 39

Table 7 Correlations for CASA Questions and ProQOL ...................................... 40

Table 8 Correlations for Empowerment and ProQOL .......................................... 41

Table 9 Mean Comparisons for Two 18 Month Cycles. ...................................... 43

Table 10 Mean Comparisons for First and Second Year Volunteers. ................. 44

vii

1.

2.

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1 Volunteer Stages and Transitions Model Diagram .................................. 5

Figure 2 Previous 18 Months Retirements by Length of Service Categories ....... 34

viii

1

Chapter 1

INTRODUCTION

Statement of the Problem

Millions of people volunteer their time every year (Omoto & Snyder, 2002).

Some researchers have defined volunteerism as an unpaid, altruistic or prosocial behavior to benefit strangers (a person, group, organization, cause, or the community at large) and usually occurring through an organization (Musick & Wilson, 2008; Penner, 2002;

Finkelstein & Brannick, 2007). Volunteerism can occur in a variety of contexts and across a range of activies, some only lasting an hour or a day (Musick & Wilson, 2008).

Governments and non-profit organizations rely heavily on volunteer labor to achieve their goals (Musick & Wilson, 2008). Brudney and Meijs (2009) propose that volunteer energy can be understood as a human-made, renewable resource that can be grown and recycled. Government officials are interested in sustaining and growing this natural resource (Brudney & Meijs, 2009). Organizations that rely on volunteerism to meet organizational goals also have an interest in attracting and retaining volunteers. In recognition of the role volunteer work plays in our society, the United States government began systematically collecting data about volunteers in 2002 (Musick & Wilson, 2008).

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (Volunteering in the United States, 2010) collects information on volunteers through a supplement to the Current Population Survey. The supplement goes to 60,000 households every month and defines volunteer work as person(s) who performed unpaid work (except for expenses) through or for an

2 organization. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (2009) estimates that 63.4 million people in the United States volunteered their time at least once between September 2008 and

September 2009. This number accounts for 26.8% of the population, which is a decline of

2% from 2005 levels (Brudney & Meijs, 2009). Due to the downward trend of volunteerism, there has been increasing interest in the attraction and retention of volunteers (Brudney & Meijs, 2009; Musick & Wilson, 2008).

A Model for Volunteerism

Existing knowledge about volunteers in the human services has focused on various aspects: defining volunteering, motivation to volunteer, volunteer retention and turnover, and personality traits of the volunteer (Haski-Leventhal, 2009). Omoto and

Synder (2002) offered a model of volunteerism with three broad and interactive stages: antecedent, experience, and consequences. Antecedent is the period when volunteers consider volunteering and organizations recruit and train volunteers. The experiences of volunteering includingassignment, support, and organizational integration are included in the second stage, experience . The third stage, consequences , includes changes in knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, and motivations. Omoto and Snyder based their model on HIV and AIDS volunteers and discussed how a sense of community can affect volunteerism; specifically, the effects of a negative bias (negative attitudes about HIV and AIDS) on volunteer experiences. However, since not all volunteers face negative social evaluation, this model may not be applicable to other volunteer organizations.

Also, this model does not fully explain transitions between the stages or possible exit points where volunteers are more likely to consider leaving the organization.

3

Penner also offered a model of volunteerism (Penner, 2002). This theory contends that organizational and dispositional factors interact to affect sustained volunteering.

Dispositional factors include personal beliefs, values and prosocial personality traits.

Organizational factors specifically mentioned were: (1) the volunteer’s perceptions and feelings regarding the way he or she is treated by an oranization, (2) the reputation and personnel practices of that organization and (3) their relationship with the organization, which involves job attitudes such as job satisfaction and commitment (Penner, 2002). The model focuses on how these two concepts have direct and indirect effects on sustained volunteerism, but does not attempt to explain the emotional and cognitive processes volunteers experience as they progress along the model’s paths. Little has been written about stages a volunteer may go through and how these stages can affect current and future volunteer activities (Haski-Leventhal & Bargal, 2008).

Haski-Leventhal and Bargal (2008) were the first to blend the theory of organizational socialization with the different aspects of volunteering (motivation to volunteer, rewards, satisfaction, etc.) and how they may change over time. Organizational socialization is concerned with the way newcomers change and adapt to the organization

(Wanus, 1991), including attaining the knowledge and skills necessary to assume a role in an organization. Roles are behavioral expectations, so performing a role means conforming to the expectations others have about the way a person should act in a given situation (Musick & Wilson, 2008). Volunteer roles in human services fields are helpful in that they allow the volunteer to provide care to people going through difficult

4 situations, but in a time limited way and without being overwhelmed (Musick & Wilson,

2008).

Haski-Leventhal and Bargal proposed the volunteer socialization and transitions model (VSTM) in 2008. It is based on research with volunteers of a non-profit organization for disadvantaged youth located in Israel. This model is more specific than

Omoto and Snyder’s model in that it has 5 stages and provides details about the transition between each stage (see Figure 1). The five stages are: nominee , new volunteer , emotional involvement , established volunteering , and retiring . Unfortunately, no research has been done on this model, and its applicability to other volunteer organizations is unknown. However, this model could provide significantly more information and support for organizations with goals that require long-term volunteers. It could also help volunteers who are working through a transition to move to the next stage. Organizations could educate volunteers and staff on these stages and implement strategies to help volunteers successfully navigate each stage with the intention of reducing turnover.

Figure 1

Volunteer Stages and Transitions Model Diagram

The Nominee Phase

Considerations of joining Organizational boundaries

New Volunteer

Ejection Accomodation

Emotional Involvement

Affiliation

Established Volunteering

Renewal or Exit Process Begins

Retirement

Exit

5

6

When a person is considering volunteering for an organization, he or she is in the first stage of nominee . This stage may last one or two months and is marked by high ambiguity and low commitment. Volunteers may have feelings of excitement mixed with fears and fantasies (Haski-Leventhal & Bargal, 2008). The transition from nominee to newcomer includes selection, training, and starting the volunteer role (Haski-Leventhal &

Bargal, 2008). It is in this phase that volunteer selection creates barriers to entry and can identify attributes that result in a good fit for the organization and the volunteer.

Depending on the organization it may include on-the-job training or formal training and some form of contract (written or psychological). This transition shatters the ideals of the nominee, as they experience the reality of the volunteer role (Haski-Leventhal & Bargal,

2008).

The newcomer stage is still a time of high organizational and role ambiguity

(Haski-Leventhal & Bargal, 2008). The model identifies this stage as occurring in the first few months of volunteering. Volunteers are thrust into their role but because their knowledge and skills are still limited, they may be of limited help. They are trying to fit into the organization or group but still feel marginalized. Romantic idealism of the previous stage gives way to limited idealism, characterized by the understanding that they may not be able to save the world but they can make an impact with what they are doing.

Volunteers may cope by being ‘emotionally detached’ (Haski-Leventhal & Bargal, 2008).

Some people will leave the organization at this point either because they reject the volunteer role or the organization rejects them; but if they stay they will enter the accommodation phase. Haski-Leventhal & Bargal (2008) identified three main obstacles

that may lead to ejection: Not fitting in with the group, unfavorable attitudes from their social environment, or lack of suitability between the individual and the organization.

The accommodation transition usually occurs after a meaningful event or an experience where volunteers feel like they have helped. Once this occurs, their perceptions may change and they may feel more capable, skilled, needed and satisfied

(Haski-Leventhal & Bargal, 2008). Skilled volunteers will then move on to the third stage, emotional involvement .

Emotional involvement is an important phase that Haski-Leventhal and Bargal

(2008) note is often absent from socialization theories. In the model it is identified as occurring in the first 4 to 8 months of volunteering. In this phase the detachment used as a coping mechanism in the last stage is replaced by a deep emotional involvement. The relationship between volunteers and their clients becomes deep and long-term.

Volunteers feel more skilled and able to perform their role. The challenge in this stage is merging volunteering with the individual’s personal life. This can lead to dilemmas such as how this deeper relationship can be communicated without stepping over boundaries

(e.g., wanting to hug clients). Perceptions of their roles are characterized by “sober idealism” (Haski-Leventhal & Bargal, 2008; p. 86). This is a time of turbulent emotions with high excitement and satisfaction mixed with deep sadness as volunteers are emotionally exposed to the traumatic realities of those they help. Volunteers are highly committed at this stage, they are likely to find their work meaningful and important and express high self-efficacy, confidence, and enthusiasm (Haski-Leventhal & Bargal,

2008). With the passage of time these committed volunteers improve their skills and

7

8 become senior volunteers who are able to mentor others; this marks the transition from emotional involvement to established volunteering and is called affiliation (Haski-

Leventhal & Bargal, 2008).

The fourth stage, established volunteering , usually occurs after a year of service and is a time when the volunteer either experiences a renewal process, or begins the process of exiting the organization. (Haski-Leventhal & Bargal, 2008). Volunteers’ perceptions change to reflect the limitations of their helping efforts and they become realistic or even cynical. It is during the established volunteering stage that burnout is most likely to occur. Haski-Leventhal and Bargal state, “Volunteers who do not go through ‘renewal’ may experience burnout, fatigue and detached concern, eventually leaving the organization” (p. 74).

Those who do not experience renewal begin an exit transition (Haski-Leventhal &

Bargal, 2008). During the transition phase, volunteers debate whether to stay or go. The relationship they have with their client(s) often plays an important role in the decision. As a protective mechanism, volunteers may emotionally distance themselves from their clients and the organization; they may blame the clients or find fault with their supervisor in order to create distance. Haski-Leventhal and Bargal (2008) also note that “critical points” exist in the volunteer cycle which may trigger the feeling that they have “done enough” (p. 94) and can leave; anniversaries are one example. If volunteers cannot successfully renew their commitment they will move into the last stage of retirement .

Retirement is the final stage of the model. In this stage volunteers begin to emotionally detach from the organization and the clients they have served. However,

9 some volunteers may find it difficult to totally detach, so this phase can be associated with sadness and confusion. This stage is a time of looking back, reflection, and remembering the people they met along the way and the relationships they have had because of their experiences as a volunteer (Haski-Leventhal & Bargal, 2008). A volunteer’s decision to leave may increase turnover for the organization because, as friends and cohorts retire, it affects those who remain (Haski-Leventhal & Bargal, 2008).

The Role of Efficacy in Continued Volunteerism

According to the VSTM, there is a pivotal point in the volunteer lifecycle that transitions a new volunteer into the next stage of emotional involvement . This pivotal event changes the volunteer experience by increasing the feeling of efficacy and reducing the likelihood of exiting the organization early. The sense of efficacy is specifically tied to the volunteer work and is similar to the concept of psychological empowerment.

Empowerment as a construct was discussed in the early literature as a component of managerial and organizational effectiveness (Conger & Kanungo, 1988). It was often confused with the concept of managers sharing power with subordinates with little thought of the processes and constructs underlying outcomes. Conger and Kanungo

(1988) attempted to blend management and psychology theory to provide a framework for studying empowerment. Relational empowerment most closely matched the management literature as it was equated with decentralizing decision making and increasing participation in planning or goal setting. It was meant to balance the situation that occurs when a person (or organizational subunit) has decision making authority, and therefore perceived power, over others. Sharing power and delegating authority became a

10 central concept of empowerment in management literature (Conger & Kanungo, 1988).

Conger and Kanungo suggested an empowerment definition using enabling, instead of delegation and participation, to increase motivation for accomplishing tasks and increasing personal efficacy. Personal efficacy was based on Bandura’s idea of selfefficacy which was affected by either increasing perceptions of power or decreasing perceptions of powerlessness. Thus an individual’s perception of attempted empowerment was critical to its effectiveness, impacting both task initiation and persistence (Conger & Kanungo, 1988).

Thomas and Velthouse (1990) subsequently added to Conger and Kanungo’s work by offering a multidimensional cognitive model of empowerment. Their model stressed the interpretive aspect of cognitive processes that workers use to reach conclusions about tasks and not just self-efficacy. Their motivational conceptualization went beyond stimulus and response mechanisms to include the individual’s cognitions relative to the task, which in turn affect motivation and satisfaction. Their model defined the motivational aspect of empowerment more precisely, which they called intrinsic task motivation. A task was clearly delineated as, “a set of activities directed toward a purpose” (Thomas & Velthouse, 1990, p. 668).

Thomas and Velthouse (1990) expanded on task assessments that produce positive motivation and attempted to describe the interpretive processes used during assessments. The four cognitions, or task assessments, identified by Thomas and

Velthouse (1990) were: competence (similar to self-efficacy), meaningfulness (of the task itself), sense of impact (on outcomes), and choice (in initiating and regulating actions).

11

Global beliefs and interpretive styles are identified as central to the cognitive processes important to motivation. In other words, environmental factors mixed with interpretive approaches and personal beliefs construct a personal reality (task assessment) that determines if workers actually feel empowered. The assessment influences behavior which in turn provides input to environmental events that trigger the process to start again

(Thomas & Velthouse, 1990). Spreitzer (1995) summarizes the critical components of their model this way: “an individual’s work context and personality characteristics shape environment cognitions, which in turn motivate individual behavior” (p.1444).

Spreitzer (1995) added to the work of Thomas and Velthouse by creating a multidimensional measure of psychological empowerment in the workplace (Spreitzer,

Kizilos, & Nason, 1997). Spreitzer operationalized the four cognitive dimensions of task assessment and began the work of construct validation. Spreitzer also identified two personality traits, self-esteem and locus of control, that were antecedents to the concept of empowerment in that they influence how people see themselves in relation to the work environment. The work context itself was also hypothesized as an important factor in an individual’s feeling of empowerment (Spreitzer, 1995). Locus of control was not supported but other aspects of the construct were supported. Spreitzer recommended including not-for-profit organizations in future research validating empowerment.

Sprietzer, Kizilos, and Nason (1997) conducted a study that examined the relationship of the four dimensions Thomas and Velthouse originally developed against three expected outcomes: employee work satisfaction, effectiveness, and job strain. They found that no single dimension predicts all three outcomes. The results seem to indicate

12 that an employee must experience all four dimensions in order to achieve anticipated outcomes from empowerment interventions (Spreitzer, Kizilos, & Nason, 1997).

One shortcoming of the psychological empowerment literature discussed so far is the absence of questions measuring how a cherished goal or valued cause may impact an employee’s feeling of empowerment (Menon & Hartmann, 2002). Up to this point empowerment research was limited to intrinsic task motivation, focusing on the part (or task) instead of the whole (or goal). Menon (2001) suggested a measure that included questions related to the impact of a cherished goal, or cause, on empowerment.

Academic literature on empowerment falls into three approaches: structural, motivational, and leadership (Menon, 2001). The structural approach is consistent with the early view of empowerment. It is the idea that employees will be empowered when decision making authority is delegated, the hierarchy is flattened and employee participation is increased. In other words, employees with higher power share their power with less powerful subordinates (Menon, 2001). The psychological state of the employee is not considered in this approach. On the other hand, the motivational approach is more in line with the views of Conger and Kanugo (1988), Thomas and

Velthouse (1990), and Spreitzer (1995) discussed earlier. In this approach, the psychological state of the employee is central to motivation. The leadership approach is related to transformational, charismatic, visionary, and inspired leadership. Leaders are able to align employee’s beliefs and attitudes with the organization’s mission and objectives to achieve energizing effects on employees (Menon, 1999).

13

Based on these three approaches, Menon suggested a definition for psychological empowerment that included goal internalization, perceived control, and perceived competence. Goal internalization relates to the energizing principle of the leadership approach (Menon, 1999). Perceived control ties back to the structural approach of delegation and shared decision-making. Perceived competence is related to role-mastery and is supported by the motivational literature. Based on these definitions of psychological empowerment and given the support of existing literature, Menon created a measure of psychological empowerment.

Volunteers perform unpaid work and empowerment is a work related construct.

The construct of empowerment aligns with several key elements of volunteerism in general and the VSTM specifically. Motivation is frequently studied in volunteerism as is volunteer retention (persistence). The ability to feel efficacious, helpful, and competent to help is specifically cited in the VSTM; this is related to the perceived control and perceived competence constructs measured in Menon’s empowerment subscales. In particular, perceived competence is important during the early stages of volunteering.

Another critical retention point is identified in the model toward the end of the first year of service, during the established volunteering stage. At this point initial enthusiasm is diminished as sober realism takes its place, and negative evaluations may be more commonplace. Although the model specifically mentions being at high risk for burnout, other factors can also play a role. For example, Haski-Leventhal and Bargal

(2008) noted that some emotionally involved volunteers reported an almost traumatic

14 effect after exposing themselves to the distress their recipients were experiencing. This phenomenon is known in psychology literature as secondary traumatic stress.

A measure that emerged to quantify secondary trauma symptoms is Figley’s

Compassion Fatigue test. Stamm (2009) later revised the scale to include compassion satisfaction, which measures h positive feelings generated from helping. The scale is now called the Professional Quality of Life (ProQOL) scale.

ProQOL: Compassion Satisfaction and Fatigue

Compassion satisfaction and fatigue are two sides of the same concept (Stamm,

2009). When helping behavior is viewed positively and with satisfaction, compassion satisfaction is high. Similarly, according to the model, compassion satisfaction should be high when volunteers are feeling efficacious , i.e., when they feel they can help.

Compassion fatigue is the negative side of the concept that has two components: burnout and secondary traumatic stress.

Burnout was first studied in the United States in the mid-1970’s (Maslach,

Schaufeli, & Leiter, 2001). The research was originally based on experiences in the workplace rather than scholarly theory. Initial articles were written by Freudenberger, a psychiatrist, and Maslach a social psychologist. They were based on research in the service and care-giving occupations which presupposes a relationship between provider and recipient. Further research led to a conceptualization of burnout as a psychological syndrome in response to chronic interpersonal stressors from the job (Maslach, Schaufeli,

& Leiter, 2001).

15

The key dimensions of the response to job stresses were threefold: overwhelming exhaustion, feelings of cynicism and detachment from the job, and a sense of ineffectiveness and lack of accomplishment (Maslach, Schaufeli, & Leiter, 2001).

Exhaustion is the dimension of burnout characterized by feeling overextended and the depletion of physical and emotional energy (Maslach, Schaufeli, & Leiter, 2001).

Cynicism is the interpersonal dimension of burnout characterized by negative, callous or excessively detached responses and is also referred to as depersonalization. Finally, the reduction in feelings of efficacy and accomplishment characterizes the self-evaluative dimension of burnout. It relates to the feeling of incompetence and the actual or perceived reduction in productivity (Maslach, Schaufeli, & Leiter, 2001).

Similar to burnout, secondary traumatic stress (STS) is also associated with service and care-giving occupations (Baird & Kracen, 2006). Secondary traumatic stress is a set of psychological symptoms that mimic post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) but is not acquired through experiencing trauma first hand; rather, it is acquired from providing care to people who have experienced trauma (Baird & Kracen, 2006). Unlike burnout which is usually associated with longer onset, STS can materialize after a short period of time; just as trauma can be sudden, so can the onset of STS (Baird & Kracen,

2006).

Figley (1995) used the term compassion fatigue to describe the symptoms of hypervigilance, exhaustion, avoidance, and numbing exhibited by caregivers working with PTSD patients. Stamm and Figley started collaborating on the Compassion Fatigue

Test in 1988, which is when the positive aspect of compassion satisfaction was added and

16 the name was changed to the Compassion Satisfaction and Fatigue Test (Stamm, 2009).

By the late 1990’s the measure shifted primarily to Stamm, who renamed it to the

Professional Quality of Life Scale. Secondary traumatic stress and burnout have some related concepts, such as exhaustion and feelings of detachment or avoidance. However, secondary traumatic stress is specifically related to the fear of experiencing a traumatic event similar to the event experienced by the client. This fear could negatively affect the helper and cause symptoms such as avoidance and hypervigilance (Stamm, 2009).

Secondary traumatic stress is associated with caregivers who help traumatized victims. Not all volunteers are exposed to trauma victims or highly emotional interactions, but for some it can be an integral part of the volunteer work. For example, the VSTM was based on volunteers who helped disadvantaged and homeless adolescents in Israel. Their clients frequently experience high stress situations and sometimes traumatic events. Therefore, awareness of STS may need to be raised in volunteer organizations with caregivers who work with high trauma populations.

Court Appointed Special Advocates

Court Appointed Special Advocates (CASA) is a non-profit organization that recruits and trains volunteers to advocate on behalf of abused and neglected children

(What is the CASA Movement, n.d.). Every year hundreds of thousands of children in the

United States are caught in the court and child welfare system because they are unable to live safely at home. Last year more than 68,000 CASA volunteers helped more than

240,000 abused and neglected children (The CASA Story, n.d.).

17

The CASA program was started in 1977 by David Soukup, a Seattle Superior court judge (What is the CASA Movement, n.d.). He felt concern about the amount of information that was available to help make decisions about abused and neglected children, so he sent out a call for volunteers that would help judges. He created the idea of appointing community volunteers to represent, in court, the best interests of the child.

His call for volunteers resulted in a group of 50 citizens that started the first CASA program (What is the CASA Movement, n.d.). Today CASA has over 1,000 programs nationwide and has helped over two million children since inception (The CASA Story, n.d.).

Judges usually refer their most difficult cases to CASA (Barker, 2006). In most communities the need for CASA volunteers is greater than the supply. CASA is the only volunteer organization that empowers members to serve in the official capacity as officers of the court (Volunteering, n.d.). The CASA website lists four objectives for the volunteer: (1) represent the child’s voice in court, (2) assist the court by investigating and reporting on their case, (3) monitor the progress of the case to reduce delays, (4) facilitate the services needed to help the active and positive growth of the child (Becoming an

Advocate for a Child, n.d.). A CASA volunteer builds a relationship with the CASA child by spending time with them and gathering facts about their lives. They are allowed to visit the child at school and at home.

Every CASA child has their own story, experiences can differ widely. Many of the children in CASA are taken from their parents and placed in foster care. One CASA child tells the story of her childhood with a mother who was addicted to drugs; they were

18 often homeless (A Childs Story, n.d). After an overdose episode the child was placed with her paternal grandparents, who were strangers to the child. When they could no longer care for her she was placed in foster care. Her story ends well; she was adopted by a loving family. Her relationship with her CASA is so affectionate that she refers to her as Aunt Nancy. Sometimes, as in this story, the relationship is so enduring that the advocate and the child continue to stay in touch even after their case is resolved.

CASA volunteers must pass a background test and complete at least 30 hours of training (What do volunteers do, n.d.). Once the initial training is completed, volunteers are sworn in by the court and assigned to a case. CASA volunteers can select which case they will take from those that have been referred. Most CASA volunteers only take on one case at a time so that they can really get to know the CASA child and focus their efforts on helping that child. Volunteers commit to staying on the case until the child is placed in a safe and permanent home, usually around eighteen months (Volunteering, n.d.). Volunteers spend an average of 10 hours per month on a case.

CASA El Dorado is a local branch of this nationwide organization. It consists mainly of volunteers, with some paid employees (case managers, a director, and administrative support) who organize, train, and support the volunteers to ensure organizational goals are met. The 2008 annual report for CASA El Dorado indicated that

906,000 children nationally are victims of abuse and neglect every year (CASA El

Dorado, 2008). Last year 227 advocates from CASA El Dorado helped 451 children, which equated to 4,782 advocate hours donated (CASA El Dorado, 2009). CASA El

Dorado currently has approximately 152 volunteers in California. Although CASA has

19 been studied for program effectiveness and outcomes, only a few studies have looked at the volunteers themselves (Barker, 2006).

Purpose of the Current Study and Hypotheses

The present study will test the newly proposed VSTM and its assumptions about two key exit points for volunteers, levels of empowerment, compassion satisfaction, and compassion fatigue. The study has the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Psychological empowerment will be significantly lower for volunteers in the beginning of the volunteer experience than for volunteers who have passed the initial period of adjustment marked by the first exit point (e.g. experienced volunteers feel more capable and competent).

Hypothesis 2: Compassion satisfaction will be significantly higher for volunteers in their first 8 months of volunteering (from the newcomer to the end of the emotional involvement stage) than for volunteers in the established volunteering stage.

Hypothesis 3: Volunteers will experience significantly higher burnout scores after

8 months of service (during the established volunteer stage) as compared with volunteers with fewer months of service.

Hypothesis 4: Volunteer retirement will be highest during the first three months of service (0 to 3 months) and the last four months of the first year (9 to 12 months) as compared with intermediary months of service (4 to 8 months) or extended service (13 to

18 months).

20

Chapter 2

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Participants

The participants were 81 volunteers from CASA El Dorado. Ten participants were dropped because they failed to complete the questionnaires. The remaining 71 participants ranged in age from 22 to 72 years old ( M = 54.00, SD = 10.71). Eighty-six percent were female and fourteen percent were male. Ninety percent of all participants identified themselves as Caucasian, the other ten percent identified as African American

(1%), Asian (1%), and Hispanic (4%); four percent chose ‘other’ or did not answer the question. Only 7% of the participants indicated a level of education equivalent to the completion of high school or GED, 35% indicated some college, 4% reported attending a technical school, 36% had received a college degree, and 18% held an advanced degree such as a PhD. The majority of volunteers (75%) carried one CASA case, 18% were working on two cases, and only 7% of the volunteers reported having three cases. The length of service for CASA volunteers ranged from 1 month to 190 months ( M = 31.73,

SD = 34.99, Mdn = 18).

Archival CASA Exit Data

A survey of current individuals could not supply the information necessary to test the fourth hypothesis because it dealt with people who had left the organization, so

CASA administrators supplied the researcher with information about volunteers who had retired over the last 18 months. The information was extracted from historical

21 information stored in CASA El Dorado archives. There were 61 exits with volunteer service time ranging from 0 to 156 months. Records with service time over 18 months were excluded from consideration to evaluate the model and extend it to the end of a natural cycle at CASA; 16 records were removed and 44 remained in the dataset. No demographic data were provided for these participants.

Measures

Demographic Questions

The demographic questions were constructed by the present researcher and included questions about gender, age, ethnicity, and level of education. Also included were demographic information related specifically to CASA which included the number of months volunteering for CASA and the number of CASA cases (see Appendix A).

Six Likert-type questions were developed with CASA administrators on topics specific interest to CASA for improvement of their program. The questions were preceded by instructions asking participants to consider their volunteer work and select the answer that best reflects how much or little they agree with the statement (see

Appendix B). The first question asked about plans to continue volunteering with CASA in the future. This question was used in previous literature to determine intention of volunteers to remain in service (Barker, 2006). The next four questions asked how valued they felt by the courts, Human Services, Case Management (e.g. the paid case managers at CASA), and the CASA child (respectively). The last question asked for an overall feeling of satisfaction with the CASA experience. For each of the six CASA questions

22 participants had the following options: strongly disagree , disagree , undecided , agree , strongly agree ; the answers were ranked from 1 to 5 respectively.

Empowerment Scale

Menon’s Empowerment Scale (Menon, 2001) was used to assess the feelings of perceived control, perceived competence, and goal internalization related to psychological empowerment. Perceived competence was identified in the VSTM as an experience that helps volunteers move from newcomer to the emotional involvement stage. Additionally, the goal internalization subscale in Menon’s measure was a unique conceptualization of empowerment. A worthy goal, or a goal that supports an individual’s values, has also been identified in the literature as a motivational reason for volunteerism

(Finkelstein & Brannick, 2007; Musick & Wilson, 2008).

The empowerment scale contains nine items with three subscales of three items each. Items are scaled from 1 ( strongly disagree ) to 6 ( strongly agree ). An overall empowerment score is determined by the sum of all nine items. According to Menon’s guidelines, scores ranging from 1 to 22 indicate very low empowerment; scores from 23 to 40 indicate low to moderate empowerment; and scores from 41 to 54 indicate moderate to high empowerment. Similarly, the subscales range from 1 to 7 for low, 8 to 13 for low to moderate and 14 to 18 for moderate to high (Menon, personal communication, May

12, 2010). Menon reports the following alpha reliabilities: Perceived control (.86), perceived competency (.78), and goal internalization (.86). Good convergent and discriminate validity has also been demonstrated (Menon, 1999; Menon, 2001; Menon &

Hartmann, 2002).

23

Because the scale was specifically developed for use in the work environment and this study included non-paid work, the items were changed slightly to reflect the volunteer role, with the author’s approval. For example, Menon’s item “I can influence the way work is done in my department” (in the perceived control subscale) was changed to “I can influence the way work is done in my CASA case” to reflect the different organizational structure associated with unpaid work (refer to Appendix C).

The Professional Quality of Life Scale (ProQOL)

The ProQOL (Stamm, 2009) is related to feelings associated with work as a helper. It measures compassion satisfaction (CS), which comes from the positive aspects of providing care. It also measures compassion fatigue (CF), the negative aspects of providing care. This measure was chosen for the present study because it provides information on areas described in the model such as positive feelings about helping, negative feelings that lead to burnout, and information on secondary traumatic stress that could be helpful to CASA.

Compassion satisfaction is related to the pleasure derived from being able to do work well, such as being able to help others or working toward a greater good (Stamm,

2009). Higher scores on this scale represent more satisfaction related to the ability to be an effective caregiver or a high level of satisfaction with helping. One example of a question in this scale is “My work makes me feel satisfied.” This scale is composed of 10 questions which are interspersed with compassion fatigue questions. (Stamm, 2009).

Compassion fatigue is composed of two subscales, burnout (BO) and secondary traumatic stress (STS). Example questions include “I feel ‘bogged down’ by the system”

24

(from the BO subscale) and “I can’t recall important parts of my work with trauma victims” (from the STS subscale). Although both these subscales compose the negative aspects of compassion, they are not added together for a total compassion fatigue score.

Each of the subscales is calculated and considered independently.

Each subscale is composed of 10 questions; thirty items in all (see Appendix D).

Items are scaled from 1 ( Never ) to 5 ( Very Often ). Five items are reverse scored. The answers given for the ten items in each subscale can then be summed to compute the total subscale score. The raw score can be converted to a z -score, and then converted to a t score for standardization, allowing scores from previous versions of the measure to be compared to scores on the current version. Generally scores below 44 are considered low and above 56 are considered high. Alpha reliability for the ProQOL subscales was reported at .88 for compassion satisfaction, .75 for burnout, and .81 for secondary traumatic stress. The standard errors of the measure were small at .22, .21, and .20 respectively. This measure has been used in many studies and over 200 published papers support its construct validity (Stamm, 2009).

Procedures

An email was sent to 152 volunteers for the El Dorado CASA organization in

Placerville, California. Each recipient received an email from the director of CASA El

Dorado with details about the survey. An email with the survey link embedded followed one week later. Reminder emails were sent to recipients who had not replied after 10 days and three days prior to closing the survey. The survey was open from June 2010 to

August 2010.

25

An online survey service was used ( www.surveymonkey.com

). The survey consisted of several different parts. The initial screen was the consent form; if participants did not provide their consent, the program directed their web browser to the

El Dorado CASA home page. If consent was given the next screen gathered demographic information, the third screen gathered information about the CASA experience specifically, the next two sections were surveys related to the research topic and the last section was the disclosure page (see Appendix E). In order to reverse the order of the surveys for some participants, two versions of the survey were created with the only difference between them being the order of the two psychological measures. Specifically, in the first copy of the survey, the psychological empowerment survey was taken first and the ProQOL was taken last; the second copy reversed this order.

Each CASA volunteer was randomly assigned to one of the two on-line surveys.

An excel spreadsheet was created and a number for each volunteer was added. A random number generator was used to randomly choose numbers between 1 and 152 (True

Random Number Service, 2010). Duplicates were removed and new random numbers added until all numbers were listed. The top half (76) of the random numbers were used to assign recipients to the first condition (Menon’s empowerment scale first) and the bottom half were used to assign participants to the second condition (ProQOL first). The random numbers were then tied back to the initial volunteer list and two email lists were generated. The two email lists were entered into the online survey tool and an initial email was generated with a link to the appropriate survey. Thirty-nine recipients responded to the first survey and forty-two responses were gathered for the second

26 survey. All survey questions were optional except the consent to participate question and the number of months as a CASA volunteer. At the end of the survey the debriefing screen was displayed (see Appendix F).

Archival CASA Exit Data

Testing the fourth hypothesis required the use of archival data provided by

CASA. The data supplied included: start date, end date, office (South Lake Tahoe or

Placerville), retirement status (resigned versus terminated) and, if applicable, a reason for resignation or termination. Examples of reasons listed were: lack of involvement, moving out of the county, personal reasons, trainee drop, medical or health problems and job demands. Exit dates ranged from July 8, 2008 to December 3, 2009.

The retirement status data were entered into a spreadsheet. The number of months as a volunteer was computed from the start and end dates. The spreadsheet was then converted to a format that could be used by statistical software. Time was grouped into four categories for analysis: 0 to 3 months, 4 to 8 months, 9 to 12 months, and 13 to 18 months. These categories were based on the expectations of the model and extended to 18 months based on the CASA request for a minimum commitment of 18 months.

27

Chapter 3

RESULTS

Preliminary Analysis

The survey was accessed by 81 volunteers. Nine respondents only answered the consent question and one did not complete a majority of the questions. These 10 records were dropped from the data file. The one respondent that only completed the demographic screen was a male, age 60, with a high level of education and only 2 months of experience as a volunteer for CASA.

Scales were reviewed for missing values. All the empowerment questions were answered (no missing values) by all but one of the remaining participants, who did not answer any of the empowerment questions (not missing at random). Examination of missing data patterns suggested the possibility that the way the measure was delivered could have caused the participant to page forward in a way that they missed the page

(e.g., due to slow computer response causing a delay in the “next” screen request, the button may have been pressed repeatedly causing a screen to be missed). ProQOL questions had a few missing values which appear to be random. Missing values were replaced by mean values for all items included in a scale.

The subscales for the empowerment measure were then computed. Perceived control, perceived competency, and goal internalization subscales were summed to determine the total score for the empowerment scale. Alpha reliabilities for perceived

28 control (.81), perceived competency (.94) and goal internalization (.94) were in line with expectations. Alpha reliability for the summed empowerment score was .85.

The burnout subscale on the ProQOL measure had 5 items that are reverse scored which were transformed into new variables for analysis. The subscales for the ProQOL were then computed: compassion satisfaction (CS), burnout (BO), and secondary traumatic stress (STS). Reliability for the compassion satisfaction and burnout subscales was similar to expectations (.85 and .73 respectively); the secondary traumatic stress reliability was lower than expected (.68).

The original research design called for identification of time frames corresponding to 0 to 3 months, 4 to 8 months, and 9 to 12 months of volunteering.

However, examination of the distribution showed vastly unequal numbers of participants in these three groups, e.g., only 3 participants were assigned to the 4 to 8 month group. A substantial portion of the data gathered was for volunteers who had more than 1 year of service (68%). Contributing to this outcome was the fact that CASA El Dorado asks all volunteers to commit to an 18 month timeframe when they start. Therefore, length of service was grouped using the following timeframes instead: 0 to 8 months (the newcomer and emotional involvement stage), 9 to 12 months (established volunteering stage and end of first year), and 13 to 18 months (extending the model to approximate cycle completion requested by CASA); these groups will hereafter be referred to as

Group 1, Group 2, and Group 3 respectively. This grouping resulted in adequate cell sizes and similarly distributed group sizes (11, 12 and 13, respectively). Therefore 36 of the original 71 responses were used in the principal analysis of the hypotheses. Table 1

29 summarizes, by length of service, the mean scores for each of the measures and their subscales.

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics for Measures

Measure

CS

Burnout

STS

Empowerment

Control

Competency

Goal

0 – 8 Months n = 11

Mean SD

44.04

15.09

17.23

48.31

15.18

16.52

16.61

4.53

4.16

3.39

5.96

2.52

2.06

1.96

9 – 12 Months n = 12

Mean SD

40.17

16.59

16.95

47.92

14.00

17.17

16.75

6.05

3.79

4.57

4.93

3.19

1.34

2.26

13 – 18 Months n = 13

Mean SD

40.49

17.46

16.69

44.23

12.46

15.69

16.46

3.65

4.27

3.09

5.69

2.30

2.10

2.14

To address hypothesis 1, which assumes that empowerment will be significantly lower in the beginning of the volunteer experience than it will be once a volunteer is more experienced, four ANOVA’s (all athree empowerment subscales and total empowerment) were conducted and post hoc tests were performed to identify specific differences between length of service categories. A one-way between subjects ANOVA compared the mean perceived control scores for CASA volunteers who fell into three length of service categories: Group 1 (0-8 months), Group 2 (9-12 months), and Group 3

(13-18 months). The result approached statistical significance, F (2,33) = 3.08, p < .06, partial η 2 = .16. Planned comparisons using the method of least significant difference

30

(LSD) revealed that Group 1 ( M = 15.18, SD = 2.52) had significantly higher scores than

Group 3 ( M =12.46, SD = 2.29), p <.02. This result was opposite of expectations and did not support Hypothesis 1. A one-way between subjects ANOVA compared the mean perceived competence scores for CASA volunteers who fell into three length of service categories: Group 1 (0-8 months), Group 2 (9-12 months), and Group 3 (13-18 months).

The result was not statistically significant, F (2,33) = 1.96, p < .16, partial η

2

= .11.

However, planned comparisons using the LSD method revealed Group 3 ( M = 15.69, SD

= 2.10) had lower scores than Group 2 ( M = 17.17, SD = 1.34), the difference approached significance ( p <.06). Group 1 ( M = 16.52, SD = 2.06) had a lower mean than Group 2, but not significantly ( p < .41). This result provided partial support for Hypothesis 1 in that the mean for Group 1 was lower than Group 2, but not significantly. A one-way between subjects ANOVA compared the mean goal internalization scores for CASA volunteers who fell into three lengths of service categories: Group 1 (0-8 months), Group

2 (9-12 months), and Group 3 (13-18 months). The result was not statistically significant,

F (2,33) = .33, p < .72, partial η

2

= .02. Planned comparisons did not reveal any significant results. Finally, a one-way between subjects ANOVA compared the mean total empowerment scores for CASA volunteers whose time of service fell into the following categories: Group 1 (0-8 months), Group 2 (9-12 months), and Group 3 (13-18 months).

The result did not reach statistical significance, F (2,33) =2.05, p < .15, partial η

2

= .11.

Planned post hoc tests using the LSD method revealed differences that approached significance. Both Group1 ( M = 48.31, SD = 5.96) and Group 2 ( M =47.92, SD = 4.93) had higher scores than Group 3 ( M = 44.23, SD = 5.69; p ≤ .08 and p ≤ .11 respectively).

31

See Table 2 for the ANOVA results using the empowerment means which were grouped into three lengths of service categories. The predicted increase in empowerment was not supported by the data; thus the hypothesis was rejected that empowerment would be significantly lower during the first stage but higher thereafter for volunteers who had more experience.

Table 2

Analysis of Variance for Empowerment x Length of Service

Empowerment Scales

Total Empowerment

Within Group error

Perceived Control

Within Group error

Perceived Competence

Within Group error

Goal Internalization

Within Group error

33

2

33

2

33 df

2

33

2

Length of Service Categories

(0-8 Months, 9-12 Months, 13-18 Months)

F

2.05

η 2

.11

P

.15

(30.62)

3.08 .16 .06

(7.24)

1.96

(3.48)

.332

(4.78)

.11

.02

.16

.72

Note: Numbers in parentheses are mean square errors.

To address Hypothesis 2, which proposes that higher compassion satisfaction would be present during the newcomer stage, a one-way between subjects ANOVA compared the mean compassion satisfaction scores for CASA volunteers whose time of

32 service fell into three categories: Group 1 (0-8 months), Group 2 (9-12 months), and

Group 3 (13-18 months). The result did not reach statistical significance, F (2,33) =2.27, p

< .12, partial η 2

= .12. Planned comparisons using the LSD method revealed that Group 1

( M = 44.04, SD = 4.53) had higher scores than both Group 2 ( M =40.17, SD = 6.05) and

Group 3( M = 40.49, SD = 3.65; p ≤ .06 and p ≤ .08 respectively). Scores of compassion satisfaction were lower for volunteers who had served longer but did not reach statistical significance. This finding provides partial support to Hypothesis 2 which posited that new volunteers were highest in compassion satisfaction.

To test Hypothesis 3, which posits that higher burnout would be present during the established volunteer stage, a one-way between subjects ANOVA compared the mean burnout scores for CASA volunteers in three lengths of service categories: Group 1 (0-8 months), Group 2 (9-12 months), and Group 3 (13-18 months). The result was not statistically significant, F (2,33) = 1.01, p < .37, partial η

2

= .06. Planned comparisons using the LSD method revealed no significant differences. This finding did not support the hypothesis that burnout would be significantly more likely to occur after 8 months of service.

A test of the other aspect of compassion fatigue, secondary traumatic stress, was conducted using a one-way between subjects ANOVA that compared the mean secondary traumatic stress scores for CASA volunteers in three lengths of service categories: Group

1 (0-8 months), Group 2 (9-12 months), and Group 3 (13-18 months). The result was not statistically significant, F (2,33) = .06, p < .94, partial η

2

= .00. Planned comparisons using the LSD method did not reveal any significant differences. Table 3 summarizes the

33 results of the one-way between subjects ANOVA for all ProQOL subscales in three length of service categories.

Table 3

Analysis of Variance for ProQOL x Length of Service

ProQOL Subscales

Compassion Satisfaction

Within Group error

Burnout

Within Group error

Secondary Traumatic Stress

Within Group error

33

2

33 df

2

Length of Service Categories

(0-8 Months, 9-12 Months, 13-18 Months)

F

2.72

η 2

.12 p

.12

33

2

(23.26)

1.015 .06 .37

(16.68)

.06

(13.90)

.00 .94

Note: Numbers in parentheses are mean square errors.

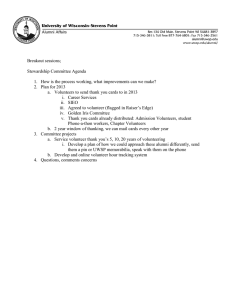

Hypothesis 4, which suggested two specific exit points for volunteers, was addressed using data provided by CASA El Dorado from archival records. A Chi Square test included all participants with no more than 18 months of service in 4 categories (0-3,

4-8, 9-12 and 13-18 months). The expected value of 11 exits per month was used in the calculation (44 people leaving evenly over 4 time categories).The hypothesis that months

0 to 3 and 9 to 12 are more likely to experience retirements was not supported by the Chi

Square test (χ

2

(3)

= 3.09, p = .38). The frequency of volunteer retirements grouped into

four time categories is presented in

34

2.

Figure 2

Previous 18 Months Retirements by Length of Service Categories

Previous 18 Month Cycle of Exits

15

10

5

0

6

13 13 12

0-3 months 4-8 months 9-12 months 13-18 months

Number of Retirements

Exploratory Analysis

Analysis of Questions Asked by CASA Administrators

Analyses were expanded to include the CASA questions as described in Appendix

B. Feeling valued by human services had the lowest mean ( M = 3.75, SD = .86) and the largest range with answers ranging from 1 to 5 ( strongly disagree to strongly agree ), indicating that overall volunteers do not feel as valued by human services as they do by other areas and that feeling valued can differ greatly in the volunteer experience. Feeling valued by case management had the highest mean ( M = 4.69, SD = .49). Feeling valued by case management and feeling valued by the child both had a narrow range, all answers fell between 3 and 5 ( undecided to strongly agree ). Table 4 shows descriptive statistics for each of the questions that were specific to the CASA experience.

35

Table 4

Descriptive Statistics for CASA Questions

CASA Questions

Intention to Remain

Valued by Courts

Valued by Human Services

Valued by Case Management

Valued by Child

Overall CASA Experience

N Minimum Maximum Mean Std. Deviation

71

70

71

71

71

71

2

2

1

3

3

2

5

5

5

5

5

5

4.28

4.33

3.75

4.69

4.21

4.30

.76

.61

.86

.49

.69

.66

A one-way between subjects ANOVA was used to compare the means of all questions specifically related to the volunteers experience with CASA, which were grouped into three lengths of service categories: Group 1 (0-8 months), Group 2 (9-12 months), and Group 3 (13-18 months). Length of service was significantly related to the intention to remain question ( F (2, 33) = 4.43, p = .02). Planned comparisons using the

LSD method revealed that Group 1 ( M = 4.64, SD = .50) had a significantly higher mean than Group 3 ( M = 3.8, SD = .80; p < .01) and Group 2 (M = 4.42, SD = .67) had a significantly higher mean than Group 3 ( M = 3.8, SD = .80; p < .05) in their intention to remain a CASA volunteer.

The degree to which volunteers feel valued by case management (the paid case managers at CASA) was highest in Group 1, lower in Group 2, and even lower in Group

3; differences approached significance. Planned comparisons using the LSD method

36 revealed that Group1 ( M = 4.82, SD = .40) had significantly higher ( p < .05) mean scores than Group 3 ( M = 4.31, SD = .63). Although the mean for feeling valued by case management was also lower in Group 3( M = 4.31, SD = .63) than in Group 2 ( M = 4.67,

SD = .49), it only approached significance ( p = .09). Table 5 summarizes the ANOVA findings for each question posed by CASA administrators.

Table 5

Analysis of Variance for CASA Questions x Length of Service

Length of Service Categories

CASA Question Scores

Intention to Remain df

(0-8 Months, 9-12 Months, 13-18 Months)

MS F

η 2 p

2, 33 .46 2.03 .21 .02*

Valued by Courts

Valued by Human Services

2, 32

2, 33

Valued by Case Management 2, 33

Valued by Child 2, 33

.47

.99

.27

.67

.047

.98

3.05

.585

.00

.06

.16

.03

.95

.39

.06

.56

Overall Satisfaction with

CASA

* p < .05

2, 33 .53 1.48 .08 .24

Correlations were performed for each of the CASA questions and all of the scales and subscales using two-tailed tests and an alpha level of .05. A significant negative relationship exists between length of service and intention to remain such that the longer a volunteer has been with the organization, the less likely they are to have a high intention of staying a volunteer ( r = -.42, p = .05). Feeling valued by case management

37 was negatively related to length of service which means that more experienced volunteers tend to feel less valued by case management ( r = -.34, p < .05) as well as report a low intention of remaining a volunteer. No other variables were significantly related to the length of time a volunteer has served.

The significant relationship between intention to remain and feeling valued by both case management ( r = .36, p < .05) and the child ( r = .49, p = .01) may be important for improving retention. Not surprisingly, intention to remain was significantly related to overall satisfaction with the CASA experience ( r = .53, p < .05) and compassion satisfaction ( r = .51, p < .01). Intention to remain was also positively and significantly related to overall empowerment ( r = .47, p < .01), perceived control ( r = .54, p < .01), and goal internalization ( r = .35, p < .05) indicating that feeling more empowered supports continued volunteerism.

Feeling empowered, perceived control, and goal internalization were significantly related to feeling valued by the courts ( r = .46, .47, and .46 respectively, p < .01), indicating that volunteers feel empowered when they also feel valued by the courts.

Feeling valued by human services was also significantly related to empowerment ( r =

.46, p < .01) as a whole and each of the subscales: perceived control ( r = .42, p < .05), perceived competency ( r = .35, p < .05), and goal internalization ( r = .36, p < .05).

Higher ratings of feeling valued by case management was associated with higher ratings on empowerment as a whole ( r = .50, p < .01), perceived control ( r = .47, p < .01), perceived competency ( r = .34, p < .05), goal internalization ( r = .39, p < .05) and compassion satisfaction ( r = .47, p < .01). Secondary traumatic stress and burnout both

38 had a significant negative relationship with feeling valued by case management ( r = -.34, p < .05 and r = -.42, p < .01 respectively). So, as feeling valued by case management went down the ratings for both STS and burnout increased.

Feeling valued by the child was positively and significantly related to empowerment ( r = .61, p < .01) and the subscales for perceived control ( r = .63, p < .01) and goal internalization ( r = .48, p < .01). Compassion satisfaction was also positively and significantly related to feeling valued by the child ( r = .53, p < .01). As would be expected overall CASA satisfaction is significantly related to all of the questions relating to feeling valued by: the courts ( r = .65, p < .01), human services ( r = .38, p < .05), case management ( r = .43, p < .01), and the child ( r = .78, p < .01). Goal internalization, which had no significant ANOVA results, was significantly related (at a point of .05 or less) to all the CASA specific questions except intention to remain. Tables 6, 7, and 8 summarize the correlation values of each variable presented in this study, using data from the 36 participants that were included in the principal analysis.

39

Table 6

Correlations for CASA Questions and Empowerment

Measure 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 8a 8b 8c

----

1.

Length of

Service

2.

Intention to

Remain

3.

Valued by

Courts

4.

Valued by

Human Srvcs

5.

Valued by

Case Mgmt

6.

Valued by

Child

7.

Overall CASA

Satisfaction

8.

Overall

Empowerment

8a.

Perceived

Control

8b.

Perceived

Competency

8c.

Goal

Internalization

* p < .05, ** p < .01

-.42

*

.06

-.16

-.34

*

-.09

-.12

-.18

-.30

-.08

----

.30

.27

.36

*

.49

.53

.47

.54

-.00

.35

**

**

**

**

.21

*

----

.56

** ----

.32

.11

----

.39

*

.65

.46

.47

.46

**

**

**

.14

**

.38

*

.46

**

.35

*

.30

.29

----

.43

**

.50

**

.42

* .47

**

.34

.36

* .39

*

*

.78

**

.61

**

----

.67

**

.63

** .64

**

.32

.40

*

.48

** .57

**

----

.83

**

.81

**

----

.46

**

.83

** .46

**

---

.65

** ----

40

Table 7

Correlations for CASA Questions and ProQOL

Measure 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

1.

Length of

Service

2. Intention to

Remain

3. Valued by

Courts

4. Valued by

Human Srvcs

5. Valued by

Case Mgmt

6. Valued by

Child

7. Overall CASA

Satisfaction

8. STS

9. Burnout

10. Compassion

Satisfaction

----

-.42

* ----

.06 .30

-.16 .27

----

.56

-.34

* .36

* .32 .11 ----

-.09 .49

-.12 .53

**

**

.39

.65

**

----

**

.38

*

.43

**

.78

**

----

-.07 .02 -.13 -.13 -.34

*

-.09 -.10 ----

.24 -.31 -.15 -.23 -.43

**

-.26 -.26 .60

**

----

Note : STS = Secondary Traumatic Stress.

* p < .05, ** p < .01

*

.30 .29 ----

-.25 .51

**

.24 .18 .47

**

.53

**

.53

**

-.24 -.67

**

----

Compassion satisfaction was significantly correlated to empowerment scores ( r =

.59, p > .01) and each of the subscales: perceived control ( r = .59, p > .01), perceived competency ( r = .36, p > .05), and goal internalization ( r = .46, p > .01). It was also

41 significantly negatively related to burnout ( r = -.67, p > .01) but not significantly related to STS. Burnout was significantly related to STS ( r = .60, p < .01) indicating that higher scores on burnout are related to higher scores on the STS subscale.

Table 8

Correlations for Empowerment and ProQOL

Measure 1 1a 1b 1c 2 3 4

1.

Overall

Empowerment

1a.

Perceived

Control

1b.

Perceived

Competency

1c.

Goal

Internalization

2.

STS

----

.83

**

.81

** .46

** ----

.83

**

-.01

----

.46

**

.07

.65

**

-.05

----

-.07

----

3.

Burnout

4.

Compassion

Satisfaction

-.28

.59

**

-.31

.59

**

-.20

.36

*

Note : STS = Secondary Traumatic Stress.

* p < .05, ** p < .01

-.16

.46

**

.60

** ----

-.24

-.67

** ----

First Year Compared to Second Year Analysis

The VSTM did not address how volunteers in the first year might be different from those volunteers who renew and continue to volunteer. Our sample started with 71 participants but was reduced to 36 due to the large volume of people who had volunteered for more than 18 months. To determine if there were significant differences

42 between the participants in the group studied and the group of participants that were one cycle ahead (19-36 months) a t test was performed using the means of each of the studied measures plus the CASA administrator questions. No significant differences were found, indicating that the volunteers in their first 18 months of service report feeling similar on the items included in this study to volunteers who renewed and stayed for a second cycle.

Table 9 presents a summary of the t test results.

43

Table 9

Mean Comparisons for Two 18 Month Cycles

0 – 18 Months a

19 – 36 Months b

1.

2.

Measure/Item

Intention to Remain

Valued by Courts

M

4.28

4.29

4.

Valued by Human Srvcs 3.61

5.

Valued by Case Mgmt 4.58

6.

Valued by Child 4.17

SD

.74

.67

.99

.55

.81

M

4.38

4.31

4.00

4.75

4.25

SD

.72

.48

.82

.45

.45

t (50) p

-.44 .66

-.14 .89

-1.48

-1.15

.15

.26

7.

8.

CASA Satisfaction

Overall Empowerment

4.28

.74

4.31

.60

46.70

5.70

47.31 4.42

-.48 .64

-.17 .87

-.38 .71

8a.

8b.

Perceived Control

Perceived Competency

13.80

16.44

2.85

1.92

13.25

16.88

2.49

2.19

.67 .50

-.73 .47

8c.

Goal Internalization 16.46

2.14

17.19

1.33

-1.48 .14

-.24 .81 9 Compassion Satisfaction 41.47

5.00

41.81

10 Burnout 16.45

4.08

16.31

3.85

4.41

.11 .92

.35 .73 11 STS

Note: a n = 36, b n = 16.

16.94 3.63 16.56 3.65

Participants were also split into groups by years of service: Group 1 (0-12 months; n = 36) and Group 2 (13-24 months; n = 16). The two groups were compared to see if the first year volunteer’s responses varied significantly from the second year on items and measures of interest in this research. Significant differences were found

44 between the first year ( M = 14.56, SD =2.89) and the second year ( M = 12.68, SD = 2.55) for perceived control t (43) = 2.31, p = .03. Table 10 contains the results of all means comparisons for applicable measures.

Table 10

Mean Comparisons for First and Second Year Volunteers

0 – 12 Months a

13 – 24 Months b

M SD M Measure/Item

1.

Intention to Remain

2.

Valued by Courts

4.52

4.30

.59

.70

4.14

4.29

SD

.83

.56

4.

Valued by Human Srvcs 3.78

1.04

5.

Valued by Case Mgmt 4.74

.45

6.

Valued by Child

7.

CASA Satisfaction

8.

Overall Empowerment

8a.

Perceived Control

8b.

Perceived Competency

4.26

4.43

.86

.66

3.55

4.50

4.14

4.18

.91

.60

.64

.73

48.10

5.32

45.86 5.22

14.56

2.89

12.68

2.55

16.86

1.71

16.50

1.97

t (43)

1.79

.10

.81

1.51

.55

1.22

1.42

2.31 p

.08

.92

.42

.14

.58

.23

.16

.03

*

8c.

9

10

Goal Internalization

Comp. Satisfaction

Burnout

16.68

42.02

15.87

2.07

5.62

3.96

16.68

40.70

17.05

1.98

3.33

4.65

11 STS 17.08 3.96 16.73 3.64

Note:

* p < .05, a n = 23, b n = 22

.65

.00

.96

-.91

.31

.52

.99

.34

.37

.75

45

Chapter 4

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to begin the testing of a new model for volunteerism, the volunteer stages and transitions model (VSTM). The researcher was unable to find any other studies that have attempted to test this model. The model, and this sample, reflects the experience of volunteers dealing with high risk children. A secondary purpose of the study was to provide information and feedback to help improve the volunteer program for a not-for-profit organization located in California, CASA El

Dorado.

No results were found that support Hypothesis 1 that psychological empowerment was significantly lower in the beginning of the volunteer experience and higher after the initial period of adjustment. In fact, total empowerment was highest in the group that contained the newest volunteers (0-8 months) and lowest in the group with the most experienced volunteers (13-18 months). This effect may be a result of the distancing that was discussed in the VSTM as a coping mechanism that occurs at the end of a cycle when volunteers are considering retirement. It could also be a result of working in a legal system, which can be very rigid and not encourage empowerment. This finding supports the idea that volunteers become more realistic about how much they can really help; idealism continues to degrade as more becomes known about helping limitations. Finally, the inability to find significance could be attributed to the lack of participants in the 4 to 8 months length of service group, which required that they be combined with the new (0-3

46 months) volunteers for analysis. This question should be examined further, with a larger participant pool in the newcomer (0-3 months) and emotionally involved (4-8 months) volunteer stages.

No support was found for Hypothesis 2 that compassion satisfaction will be significantly higher during the first 8 months of volunteering (from the newcomer to the end of the emotional involvement stage); although the results were not significant, they were trending in that direction. An examination of the means indicates that the mean for

Group 1 was much higher than Group 2, and the Group 3 mean was slightly higher than

Group 2. This result might be explained by the idea that volunteers may distance themselves as they approach an exit point but rebound if renewal is chosen; not all volunteers will choose renewal thus only a small rise was detected. The model does state that satisfaction can become mixed when participants feel satisfied with one aspect while disappointed with another. This mixed satisfaction state is discussed in the emotional involvement stage which only had three participants in this study; if volunteers carry these feelings into the next stage it could partially explain these results.

No support was found for Hypothesis 3 that volunteers would experience significantly higher burnout scores after 8 months of service (during the established volunteer stage). Burnout scores tend to rise over time (Stamm, 2009). Interestingly, that trend was not found in these results as burnout was distributed fairly evenly across all time categories. Scores tended to fall between 10 and 20 with few exceptions; these scores indicate a low level of burnout (an average ranking of 2 in a scale from 1 to 5).

Reliability for the subscale was reasonable (.73), but not high.

47

No support was found for Hypothesis 4 that volunteer retirement will be highest during the first three months of service (0 to 3 months) and at the end of the first year (9 to 12 months). In fact, the 4 to 8 month timeframe suggested by the model as being a time of high emotional involvement had the same number of exits as the end of year group. This may be a result of the training and commitment requested of new recruits. Haski-

Leventhal and Bargal (2008) did not mention if a commitment was requested from the volunteers on which they based their model. Recruits may prolong leaving, perhaps into the 4 th

or 5 th

month, not because the organization is a good fit for them but because of the training they receive, the commitment they make to the court (being sworn in as an officer of the court), and their initial commitment to CASA for approximately 18 months.

The information used for testing the fourth hypothesis was gathered from historical data leaving a paucity of information by which to formulate reasons for this trend. Future longitudinal studies could be conducted to capture data over a specified time period and gather more information about demographic data of the person exiting, reason for leaving, fit for the organization, fit with the child, and level of burnout and compassion satisfaction.