USING VIDEO MODELING AND SOCIAL CONSEQUENCES TO INCREASE THE

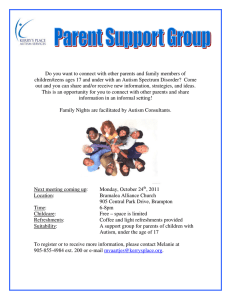

advertisement