Increased Economic Openness and the ... employment: Some issues vis-a-vis size and level of development...

Increased Economic Openness and the interface between trade, technology and employment: Some issues vis-a-vis size and level of development in case of India and China

Shipra Nigam

The impact of increased integration through trade on income and employment within the developing world has been the subject of widespread debate during the past few decades.

While problems that arose in case of the differing growth trajectories of Latin American and African countries have been widely acknowledged and affected subsequent policy debates as well as initiatives, there seems to be an emerging consensus that growth rates have actually risen in case of most Asian countries that have witnessed trade and economic liberalisation, with China and India being now widely posited as the new

‘success stories’ of contemporary globalisation.

High and sustained rates of growth of aggregate and per capita national income, the phenomenal growth in trade and investment flows and the absence of major financial crises are all invoked in characterizing this success. These in turn are often viewed as the consequences of “far-sighted”, cautious yet comprehensive programmes of global economic integration and domestic deregulation, as well as sound macroeconomic management in case of both these countries ( especially in case of China). However, where the contentious issue of the impact of these changes on nature and level of employment in these countries is concerned, the consensus is far from clear.

The impact of this rapid growth and trade integration on the growth and structure of employment becomes crucial for these labour abundant developing countries facing major challenges in the area of employment. This paper intends to map the interface between rising trade, growth and employment in an era of increased economic integration

1

while focusing on its impact on the labour markets of these Asian giants.

There are broader issues of alternative macroeconomic adjustment policies, the movement of finance capital, exchange rate managements etc which would have implications for global and domestic growth and employment. However the focus here is on rising global trade integration and changes in policy regimes leading to trade and

1 It is important to clarify over here that the basic emphasis of the proposed study is on the impact of trade rather than that of trade liberalization on employment through its impact on technological dynamism. This is a broader question which focuses on changes in a country’s integration with the global economy rather than just on its trade policy, although of course trade policy is a key factor in determining the impact of trade on employment.

investment liberalization alongwith correlated changes in technological dynamism which could have a significant impact on the output and employment growth patterns of these large developing countries.

Accordingly this paper is divided into three major sections. The first section explores the theoretical issues involved where the interface between rising trade integration, growth and employment is concerned in an era of increased economic openness. The second section carries out a survey of empirical trends in trade integration and changing patterns of output and employment in the post liberalization era in case of India and

China focusing specifically on the last one and a half decades. The analysis is carried out at various levels of aggregation (macroeconomic, sectoral and 3 digit Industrial classifications) and also involves estimation of point elasticities. The concluding section summarises the trends in context of the theoretical discussion carried out in the first section. While marshalling available evidence on trade, growth and employment, the paper a establishes that the "comparative advantage" notion of greater trade absorbing labour or raising wages does not work .Further, it suggests the existence of structural processes emerging in the context of contemporary global economic integration, which as a result of mutually reinforcing influences (export orientation and international technological diffusion) keep pushing large labour abundant developing economies in a direction which involve potential underutilization of their labour reserves. It concludes with possible ways on proceeding with further analysis to explore the possibilities of this hypothesis.

India and China – Large developing countries and the interface between trade, technology and employment

The debate on the effects of increased economic openness and trade liberalisation on employment, leading either to a virtuous process of growth or forms of “jobless growth’ in the developing world is an old one which has acquired new dimensions in contemporary literature on growth and development. Given the importance of overall employment as a crucial indicator of economic welfare, especially where a large part of the developing world characterised by the absence of any kind of social security

measures is concerned, the debate has spanned several important issues. In particular, the impact of trade liberalization on the growth of output and employment and hence its impact on poverty, wage and income distribution and the nature of employment within the developing world has been widely contested in the literature.

The complex dynamics arising out of the interface between increased trade integration, technology and employment for developing economies, I would argue, devolve crucially on the questions of size and level of development of the economy concerned and hence becomes especially important in the context of developing countries like India and China with their large domestic product and labour markets and potential for unleashing the process of technological dynamism on a large scale. Given that both these countries have experienced rapid economic integration and growth in output but with important differences in the degree and extent of structural transformation, they also provide excellent grounds for a study from a comparative perspective.

The tenets of the standard theory based on the principle of comparative advantage predict several positive outcomes of trade liberalization for developing countries typically found to be abundant in unskilled labour. These include increased efficiency of resource allocation, higher growth alongwith an increase in employment opportunities and wages for unskilled labour, and a reduction in wage and income inequalities. The common a priori assumption is that in developing countries, given their labour endowments, the unskilled labour intensity of export oriented industries is higher than that of importcompeting sectors so that ultimately trade liberalization should bring about an increase in overall labour demand

2

, especially for unskilled labour.

The assumptions 3 which go behind establishing these propositions have been widely criticised for their unrealistic nature in a world characterised by uncertainty, increasing returns to scale and market imperfections. Subsequent models 4 within mainstream theory have attempted to drop most of these assumptions with differing implications for patterns of and gains from trade. At the same time, a rich literature has also developed within

2 Here overall demand is used in the production function sense of a lower demand for K/L rather than in the

Keynesian sense.

3 These include constant returns to scale, perfect competition, strong factor intensity.

4 These include those developed by Findlay (1978), Parentte and Prescott(1998), Prescott (2000), Krugman

(1995).

economic heterodoxy,

5

again with varying implications in terms of predicted outcomes on output and employment within the developing world. Besides its theoretical critique of the logical consistency of the premises and real world relevance of the assumptions employed in standard models which have their roots in HO and SS theory, it has also been pointed out in this literature that available empirical evidence fails to conclusively establish the basic propositions of mainstream theory.

During the last 20 years, a generalized reduction in the aggregate demand for labour paralleled the developments in international trade (See ILO (1995, 1998-1999, 2005, for an overview). The unemployment rate has been growing on average across countries alongwith a falling share of wage income in total income and rising wage and income inequalities.

6

To the extent this phenomenon has became increasingly evident in case of labour abundant developing economies as well as the developed world, it necessitates a search for alternative explanations. In this context, the role of technological diffusion accompanying increased economic integration in determining the level and nature of employment conditions has served as an important point of departure in explaining divergence in observed patterns of growth and employment accompanying increased trade integration from those expected on the basis of a conventional understanding of the principle of comparative advantage. Given the importance of capital and skill biased transfers of technologies developed in advanced capitalist countries in case of developing nations, its implications for conditions prevailing in their labour markets have again been widely discussed in existing literature. Once one gets into the realm of the possible interfaces between trade and technology and its consequent implications for employment , the issue can be approached from two alternative perspectives which are however not mutually exclusive.

The age old debate on appropriateness of technology transfers developed in the advanced capitalist nations and dictated by the need for saving labour has been an important factor in influencing theoretical and policy analysis on the apposite trade and investment policies to be pursued by developing nations. The debate has also devolved on the questions of feasibility/possibilities of utilising existing repository of scientific

5 See Patnaik (2006),Wood (1994), Feenstra and Hanson (1995), Rodrik (1997)amongst others.

6 Revenga, 1992, 1995; Wood, 1997; Robbins, 1996; UNCTAD, 1997, Cornia (2006)

knowledge perse

7

which could be adapted to develop suitable non mechanised methods of production which are modern and technically efficient in case of developing countries as opposed to transfers of capital intensive techniques developed in advanced capitalist countries. Where some of the earlier discussions

8

are concerned, Salter’s (1966) contention in favour of the former was critiqued by Rosenberg (1976) and Findlay (1978) on grounds of non feasibility in terms of escalating transfer costs and skill requirements involved in such adaptive transfers suited to factor endowments of concerned countries vis-à-vis merely transfers of available capital intensive techniques where international technological diffusion arising out of increased trade and FDI flows are concerned.

However, significantly, Findlay here goes on to analyse the possibility of development of alternative growth trajectories based on generation of “intermediate technologies” for large developing nations like India and China as compared to smaller ones with similar relative factor endowments due to potential for higher gains that accrue with larger volumes of demand .

Recently, it’s been pointed out that arguments based on non feasibility of transfers of technological knowledge -that is increasingly disembodied, codified, and global and could unleash a technological dynamism of its own- loose their significance given that virtually costless transfers have been made possible with the development of sophisticated software and IT related services. However, empirical analysis has shown that non-codified knowledge continues to be important for understanding patterns in the creation and diffusion of knowledge (von Hippel 1994, Teece 1977) and to that extent role of international economic activity in determining overall technological diffusion continues to be important.

What is more important to note in this regard is that while these arguments devolve on merely the feasibility of differing kinds of technological transfers, a host of other factors are important in determining the actual nature and extent of diffusion accompanying increased economic openness, such as the pattern of trade and production that a country finds itself embarking upon consequent to its integration with the global economy . As

7 Referred to as “book of blueprints” by Joan Robinson in her discussions on production functions.

8 Salter (1966), Rosenberg (1976), Findlay (1978).

such the structural implications for changes in the labour market conditions of these countries need to be more fully explored.

The new growth theorists

9

for instance emphasise the effects of trade on diffusion of technical innovations, changing the technological level of the less advanced country. The consequent reallocation is biased in favour of skilled labour, since the technology being used was developed in the country where this factor is abundant as a result of which the structure of labour demand tends to move in favour of skilled labour. This leads to an increase in the returns to human capital manifested in increased inequality and employment effects due to skill shortages. Given that the mean elasticity of substitution of skilled labour for unskilled labour is larger in developed than in developing countries given the larger supply of skilled labour in the former

10

, the effects are more intensely felt in case of the latter countries.

However, it can be pointed out over here in view of the above discussion that technology transfer to developing nations essentially involves a process of ‘productive implementation’ as distinguished from ‘innovation’ which do not guarantee dynamic change in the technological level of production in developing nations. To that extent, any skill shortages that occur are bound to be transitional as labour markets adjust to changes in the structure of labour demand, but with the period of transition varying according to characteristic features of the existing labour market conditions.

Rising trade integration greatly facilitated by technological change has segmented production processes and allowed for the locational breakup of segments of individual processes with differing types of skill requirement alongwith associated geographical separation of different parts of the production process and increase in intra-industry trade

(Feenstra 1998). Available evidence

11

also suggests that the relative importance of

9 Grossman and Helpman (1991), Parente and Prescott (1994) and Romer (1990) etc

10 This is meant in the sense of existence of a larger pool of labour with basic skills suited to technological developments existing in case of the developed south besides a larger resource base and greater facility of converting unskilled to skilled labour, e.g. education and training facilities etc.

11 See Coe, Helpman, and Hoffmaister (1997),Connolly (1998), and Mayer (2001) Keller (2001). However primarily due to the much greater difficulty in obtaining comparable and high-quality data for less developed countries, there is a relative scarcity of results in this regard.

foreign sources for productivity growth is increasing in both size and level of development and some estimates put the relative importance of foreign technology for developing countries at almost 90% and even higher. At the same time, there is no indication that international learning is inevitable or automatic, merely a function of what

Gerschenkron (1962) has called economic backwardness. Instead, differential learning effects seem to be in part explained by the extent and the way in which firms of different countries engage in international economic activities .

The questions of the size of the country involved become important not only in terms of the scope and level of technological dynamism that can be unleashed and the possibilities of embarking on alternative growth trajectories but also in terms of the stakes involved given the existence of large labour reserves in such economies. This could be seen in light of the hypothesis recently advanced by Prabhat Patnaik (2006) on the technologyemployment-growth interface that occurs in developing countries as a result of increased trade openness in an era of globalised finance accompanied by increased restrictions on the capacity of the state to intervene. According to him, the “opening up” of an underdeveloped economy to trade and capital flows implies that the pace of technological and structural change within the economy gets linked to what prevails in the advanced capitalist world. This implies an increase in the rate of growth of labour productivity compared to what prevailed under dirigisme. At the same time the rate of GDP growth becomes dependent upon the rate of growth of exports, which, unless the underdeveloped countries erode each other’s market share, gets linked to the rate of growth of world trade, which is essentially outside the country’s control. If the rate of growth of labour demand, which is the result of these two phenomena, falls short of the rate of growth of the work force, then the ratio of labour force to work-force increases, which means a constancy of the wage rate of workers at the subsistence level and increase in absolute poverty for a larger section of the work force. This then is put forward as an explanation of the “peculiar trap” in which developing countries find themselves where rising unemployment occurs without commensurate rise in subsistence wage levels as would be expected on lines of conventional wisdom.

A proposition which clearly emerges from the above discussion is that in contemporary globalization, there are important issues regarding the patterns of revealed as well as consequential comparative advantage in trade and its implications for the nature and level of technological dynamism in developing nations caught at specific ends of the global value added chains which would determine their particular growth and employment trajectory. These become especially crucial in case of China and India given the sheer size, development potential as well as the vast labour reserves of these economies. In what follows, a survey of the recent trends post economic liberalisation in both these countries is undertaken to map the interface between trade, growth and employment.

A survey of recent trends in trade, growth and employment

As far as China is concerned, severe limitations on data availability and comparability during pre and post reform periods exist, as a result of which several studies scrutinized available statistical data

12 to arrive at more acceptable estimates of output and employment which can be used. The basic data sources include China’s statistical yearbooks, National Accounting Statistics and household surveys. In case of India too, there exist severe various data limitations where informal and rural employment are concerned. This study is going to employ a combination of international data sources such as those provided by the World Bank and the UN for comparative purposes as well as available studies based on national estimates in case of both the countries. In what follows, descriptive statistics on trade and production followed by calculation of employment elasticities following standard methodology used by ILO/ UNDP are presented.

Rising trade integration, interdependence and growing trade in goods and services

12

See, for example, Knight and Xue (2004) and Giles, Park and Zhang (2005). The few studies with a broader focus include Fang (2004), Rawski (2002) and Brooks and Tao (2003).

Overall indicators of the extent of trade integration in terms of both the domestic economy as measured by the share of exports and imports in GDP as well as the global economy as measured by the share of a country’s exports and imports in global exports and imports show that although both countries have become increasingly integrated with the World Economy, China has gone much farther , including the fact that China started the process of integration at least a decade earlier. Thus with twice as much or more share of exports and imports in GDP, more than seven times (five times) the share in

World merchandise exports (imports), the share of international trade (exports and imports of good and services) in its GDP at 66% is very high for an economy of China’s continental size and level of per capita income

13

.

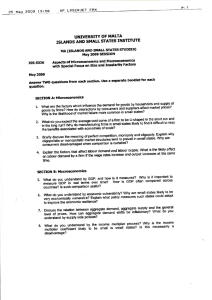

Table 1

Measures of Integration with the World Economy

Percent of Total

Share in GDP of Exports of Goods and Services

Share in GDP of Imports of Goods and Services

China

India

China

India

1983 n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a.

1994

18 1

7

1

14

1

9 1

2004

34 2

14

2

32

2

16 2

Country Share in World Exports of

Merchandise

Country Share in World Imports of

Merchandise

Country Share in World Exports of

China

India

China

India

China

1.2

0.5

1.1

0.7 n.a.

2.8

0.6

2.6

0.6

1.6

6.7

0.8

6.1

1.1

2.9

13 There could be some overestimation over due to problems with national income accounting and revised estimates being carried out might lower this figure.

CHINA

Commercial Services India n.a. 0.6 1.9

Country Share in World Imports of China n.a. 1.5 3.4

Commercial Services India n.a. 0.8 2.0

1 Shares are for 1990

2 Shares are for 2003. With newly revised GDP data for China showing higher levels of GDP, the shares would be somewhat lower.

Sources: T.N.Srinivasan (2006), China, India and the World Economy.

During the period 1990-2003 while the share of exports and imports in India’s GDP almost doubled, the increase in share in its World merchandise exports, proportionately, was far less. However given its success in the IT service sector, India’s share in World exports of commercial services tripled during the same period. It would seem that in

India’s case, with the possible exception of services the effect of greater integration is largely one-way and domestic, in the sense of its influencing the rate of GDP growth and the share of trade in domestic GDP, rather than India’s more rapid GDP growth influencing global GDP growth significantly (table 1). Both countries have witnessed a significant rise in the average annual growth rates of exports and imports during the 90’s which rose further during 2000-2006 (table 3) with the growth rates again being higher for China. While China has had a continuous trade surplus, India experienced a continuous albeit declining trade deficit until very recently.

Table 2

Share in

Global GDP

(%)

Share in GDP of Growth Rate of

Low and Middle

Income Countries

GDP (%)

1990 2003

(%)

1990

Share in Growth of World GDP

(%)

Share in Growth

Rate of Low and

Middle Income

Countries (%)

2003 1980-90 1990-03 1980-90 1990-03 1980-90 1980-03

INDIA

1.6 3.89 8.87

1.5 1.64 7.92

19. 9

8.4

10.3

5.7

9.6

5.9

5.1

2.5

13.3

3.5

30.5

15.0

51.6

13.4

CHINA AND

INDIA

3.1 5.53 16.79 28.3 7.6

SOURCE: T.N.Srinivasan (2006), ‘

China, India and the World Economy.’

16.8

Table 3

45.5

Exports of goods and services

(Average annual

% growth)

Imports of goods and services

(Average annual % growth)

Growth rate of

GDP

1980-

1990

1991

14

-

China India

6.01 5.93

China India

8.14 6.55

China India

9.21 5.89

2000

2000-

2006

14.46 13.03

24.84 16.94

16.92 14.80 10.45 6.03

20.24 12.32

Source: World Development Indicators 2006.

9.35 6.49

The change in structure of growth in trade has occurred at three levels, first within overall exports/imports between goods and services , second, within merchandise exports between primary products and manufactures and, third, within manufacturing between products of industries with varying labour intensity and levels of technology .

Between goods and services, the biggest change has taken place in Indian exports.

While both India and China have experienced higher service export growth rates, the emergence particularly of “outsourced” IT services from India has led to a structural shift with an increased the share of service exports in total exports from 20% in 1990 to 27.4% by 2003. In case of China, the share of goods exports has been rising with the share of

65.0

14

services exports in total exports falling steadily from 12% in 1982 to 7.66% in 1990 to

4.67% in 2003 (Table 4 and 5).

Table 4

China

Merchandise exports growth rate

India

80’s

8.1

90’s

9.3

80’s

13.4

11.7

90’s

15.4

18.6

Service exports growth rate

Merchandise imports growth growth rate

5.1

5.0

15.9

8.7

Service imports growth growth rate

9.6 17.8

Source: World Development Indicators 2006.

Table 5

1982

CHINA

Goods exports as as

%age of

Total

Exports of goods and services

85.43

Services exports as

%age of

Total

Exports of goods and services

11.86

INDIA

Goods exports as

%age of

Total

Exports of goods and services

72.27

Services exports as

%age of

Total

Exports of goods and services

22.97

12

11.8

16.1

28.2

1990

2000

2003

85.31

85.29

87.46

7.66

5.71

4.67

78.32

69.25

68.59

Source: World Development Indicators 2006.

19.81

26.71

27.04

Where the structure of service exports is concerned, India’s experienced a significant shift towards computer, communications and other services with their share in total commercial service exports more than doubling from 30% in 1980 to 70 % in 2003 while the share of travel and transport services fell steadily during this period. In case of China, the shift has been less dramatic with the share of computer, communications and other services in total commercial service exports rising from 22% in 1990 to 45% in 2003 and falling to 39% in 2005. The corresponding share of transport services has been falling while the share of travel services has risen during the same period (appendix table 6 and

7). As far as imports are concerned, while the share of Insurance and financial services has risen for both India and China over this period , it fell from 11% to 6.5% of total commercial service exports between 2000-2003 for the former while it rose almost four times for China during 1990-2003. The share of Computer, communications and other services as well as travel services in total imports has also been rising while that of transport services has been falling for both countries ( See appendix tables 8 and 9).

Within merchandise exports, major structural changes are taking place vis-à-vis a shift towards manufactures from primary products with the share of primary products in total exports falling for both India and China, the decline being more pronounced for china.

The evolving structure has meant large and growing trade surplus in manufactured goods but a small and declining surplus in agricultural commodities (Table 10). China was a net agricultural exporter of $2 billion in 1990. By 2003, this had been transformed into net imports of $14 billion.

The food surplus remained almost constant at around $ 3 billion for India during this period (UNDP 2006).

Where share in global markets is concerned, China has emerged as a major exporter of manufacturers since 1990 with a global share of 8.3% in 2004. India is not yet a major exporter to the world. Within manufacturing, China has a significant share of world

markets for iron and steel, office machines and telecommunications equipment and in textiles and clothing . Except for textiles and clothing

, where India’s share has grown modestly to 4.0% and 2.9% of global exports and less so to 1.6% in iron and steel exports, India’s shares are very small and not growing .

The share of low technology, labour-intensive and resource based products, representing largely the traditional exports remained more or less unchanged (Srinivasan 2006).

As far as the shifts in factor contents of country specific commodity structure are concerned, both the nations experienced a distinct fall in the share of primary commodities in total exports towards manufactures. In case of manufactures, China experienced a substantial shift towards the exports of High and medium skill and technology products especially electronics and communications equipment, parts and components over the period 1987-2003. Although, India too experienced a rise in the share of low, medium and high skill and technology intensive manufactures, especially non electrical machinery, Industrial chemicals, iron and steel and parts and components, the share of labour and resource intensive manufactures remains substantial - it rose from

27.8% of total exports in 1975 to 48.5% in 1995 while declining to 40.3% in 2003.

Interestingly, the share of textiles in total exports has been falling for both the countries

( Appendix Table 10).

Where imports are concerned, not surprisingly there has been a rise in primary commodity imports. For both India and China though the share of medium skill and technology intensive manufactures has fallen ( from 27.7% in 1987 to 20.1% in 2003 for

China and from 17% in 1985 to 10.4% in 1990 for India), the share of high skill and technology intensives manufactures has risen slightly for China while its fallen for India during this period. In case of labour and resource intensive manufactures imports China has witnessed a substantial decline (from 12.9% to 6.9%) whereas India has experienced a rise (from 8.2% to 13.5%) during the same period (appendixTable 11).

To sum up, structural changes in growing trade towards more technology intensive manufactures has been much more pronounced in case of China, both in terms of there share in total domestic exports as well as in global merchandise exports. India however has experienced a rapid rise in more technology intensive services .

Changing Production and Labour market conditions

The growth success and questions of sustainability

China’s GDP grew the fastest in the world at an average rate of 10.3% per year during

1980-90, while India’s grew at 5.7% (World Bank 2005). This difference between the remarkably high growth rates of GDP in China and the more moderate though sustained growth in case of the Indian economy has also started narrowing recently. The Chinese growth has been relatively volatile around the trend growth rate of 9.8 while the Indian economy broke from its average post-Independence annual rate of around 3 per cent growth to achieve annual rates of more than 5 per cent from the early 1980s. However in the most recent period ( 2003- 2007) the Indian economy has apparently grown at rates in excess of 8 per cent per annum, coming close to the Chinese average.

In terms of absolute level of Gross National Income (GNI) at Purchasing Power

Parity (PPP) exchange rates in 2003, China, with $10.15 trillion in GNI, was second largest in the World ( just behind the U.S figure of $ 13.23 trillion) with India falling marginally behind Japan ($ 4.22 trillion approx) in the fourth position with a GNI of

$4.21 trillion. According to IMF (2005), India’s share in global output at PPP exchange rates rose from 4.3% in 1990 to 5.8% in 2004, and India’s growth during 2003 and 2004 to have accounted for one-fifth of Asian growth and one-tenth of World growth, as compared to China’s contribution respectively of 53% and 28% (Table 1).

The shares of the two countries (GDP levels and growth) have been increasing over time, although more so in the case of China than India. The two together accounted for more than a sixth of global growth during 1990-2003 and account for a large share of

GDP and growth of low and middle income countries ( Table 2 ).

Their exists a high correlation between the remarkable rates of growth in China and its corresponding rates of domestic investment and capital formation as a share of GDP

(varying between 32 per cent and 44 per cent of GDP) which have been very high by global standards and a large part of them has been directed towards manufacturing and related sectors. According to Chandrasekhar and Ghosh (2007), this combined with the fact that both these indicators have exhibited marked volatility around trend growth rates,

seem to suggest that the cyclical pattern of GDP growth around a high trend growth rate is related to the pattern of investment. To the extent the latter is related to trade flows, it would again have a significant impact on the structural transformation in production patterns. In case of India, the higher investment rates (around 30% in 2004-05) have largely been correlated with the growth in services.

The high rates of growth have raised the obvious questions of their sustainability in the long run, especially in case of China. These in turn involve the nature of the current growth process and its sources including supply side factors. In this regard, Srinivasan

(2006) points out that given the higher capital intensity

15

of China’s current growth process, its incremental capital output ratio was substantially higher than that of India

(6.7%). Where total factor productivity is concerned, TFP growth rose from 2.06% during 1989-1995 to 2.49% per year during 1995-2003 in case of India while China’s

TFP

16

growth fell from a dramatically high 6.33% per year to 2.49% between the same periods. Its contribution to GDP growth continued to be almost the same (41.0% and

40.0%) in the two periods in India, while it fell from 64.3% to 34.9% in case of China.

The estimates carried out by Jorgenson and Vu (2005) reveal that China witnessed a faster TFP growth than India during most of the period 1953-2003, except during 1995-

2003 when their TFP growth rates were almost the same

17

.

Sources of Output Growth in China and India (% Per Year)

Period 1989 – 1995 Period 1995 – 2003

G D P TFP GDP

C a p i t a l L a b ou r C a p i t a l L a b ou r

TFP

15 Given that manufacturing output accounts for a larger share of total output and its substantially higher investment in more capital intensive infrastructure.

16 The TFP estimates need to be taken very cautiously given notorious problems with datasets and methodologies in case of both these countries.

17 though the revised data could raise China’s estimates.

Growth

ICT

0.17

Non

-ICT

2.12 hours

0.87 qualit y

0.45 6.33

Growt h (%)

7.13

ICT

Non-

ICT hour s quality

0.63 3.17 0.45 0.39 2.49 China 9.94

India 5.03 .09 1.18 1.27 0.43 2.06 6.15

SOURCE: Jorgenson and Vu (2005)

0.26 1.77 1.22 0.41 2.49

Also, given the higher rates of investment and gross domestic capital formation (44% and 42% in case of China and 30% and 24% in case of India), it appears then that limits to investments in physical capital are already being reached in China and sustainability of the growth process would require not only a rising TFP growth but also a more efficient utilization of its existing labour force 18 . This further underlines the need for the agrarian transition of workers from low productivity primary sector to the high productivity high growth manufacturing sector in case of the Chinese economy.

Where India is concerned, the limits to growth in terms of both factor accumulation as well as TFP growth are far from being reached given the much lower levels of investment and gross fixed capital formation and hence there exists substantial scope for further unleashing its growth potential.

Jobless Growth and the incomplete agrarian transition

Where trends in employment growth are concerned, a variety of alternative estimates

19 at the broad macroeconomic and sectoral level are available, all of which however

18 Srinivasan (2006) also points out how a rise in labour force given rising population dependency ratios and very high ratios of working age population.

19 See Key Indicators of labour market (ILO), Chandrasekhar and Ghosh (2007), Ghose (2005) Palinivel

(2006), Uma Kapila (2006), Goldar (2002) among others.

indicate certain distinct trends

20

. We begin with a structural picture of output and employment shares in total value added followed by value added growth rates and estimation of employment elasticities .

A note on methodology

The standard method of calculating employment elasticities is the arc elasticity formula e io

( E i 1

E i 0

/ E i 0

) /( Y i 1

Y i 0

/ Y i 0

)

However this formula has a built in instability while calculating year over year elasticities and is thus not very appropriate for comparitive purposes. So a different approach commonly employed these days

21

is adopted using a log linear regression model with country dummy variables C interacting with log GDP to give estimates of point elasticity:

InE i

1

InY i

2

( InY i

C i

)

3

C i

i

Here

1

2 represents the change in employment associated with a differential change in output. The sectoral value added elasticities w.r.t overall GDP are then calculated

using the same formula with E representing employment by sector and for calculating value added elasticities by sector Y is replaced by V representing total value added for sector i.

Thus two sets of sectoral elasticities besides overall elasticities are calculated for the period 1992-2005 : the first give an indication of whether employment has been rising or falling in a sector relative to both overall GDP as well as other sectors. The value added elasticity gives an indication of whether growth in a sector is largely productivity driven or employment driven and hence whether trends indicate a move towards labour substituting production . These calculations are used with other estimates on output and employment shares and elasticities to arrive at a more comprehensive picture regarding the processes at work.

Where China is concerned, recruitment, remuneration as well as migration in labour markets was tightly controlled through an elaborate policy framework and state owned institutional structure until an initial relaxation of state control during early and mid

1980’s post the 1978 economic reforms. However the real move towards liberalization of

20 It must be remembered that where employment is concerned , there exist severe data limitations in case of China

21 See for instance KILM (2005) and Trade and human poverty in Asia Pacfic , UNDP( 2006).

labour market conditions came with fresh reforms in 1994 with a relaxation of state control over recruitment, working tenure and remuneration in case of both urban state owned and collective enterprises as well as rural Township and Village enterprises

(TVE’s). The institutional structure also underwent a change with liberalization of production and ownership conditions in urban and Industrial enterprises and a movement from commune systems towards a ‘new responsibility system” in rural areas which effectively brought back family farming under a fixed rent tenancy system 22 .

The impact on the institutional nature of employment is clear. Uptil 1990, a large chunk of urban employment was in state and collective enterprises and rural employment was in TVEs and in small family farms that emerged under the “responsibility system”.

By the end of the decade, the state and collective enterprises ceased to be the principal employers, and there emerged a broad variety of production and trading units in both rural and urban areas ranging from “cooperative enterprises”, “joint ownership enterprises”, “limited liability corporations”, “share holding corporations” to enterprises owned and operated by investors from Hong Kong, Macao, Taiwan province and foreign countries. A substantial numbers of recognized and registered small- scale private enterprises and individual businesses, officially recognized and registered also came into existence (Ghose 2005). As a result, the post 1990 period becomes significant in analyzing the impact of economic reforms and trade liberalisation of a more market oriented production and employment structure on both the level and nature of changes in labour market variables. However, certain important features in terms of labour market conditions in China that need to be kept in mind over here include the public provisioning of shelter, food and basic amenities alongwith the existence of externalities generated by the presence of substantial investments in heavily subsidized basic infrastructural services and activities. These imply lower input costs without implying an equivalent fall in terms of adverse welfare consequences where working conditions are concerned as a result of pro-active state intervention.

The shifts in terms of sectoral value added shares reflect the influence of external trade patterns post opening up and the consequent implications in terms of being caught at specific ends of global value added chains. During the initial decade and a half of reforms

22 See Ghose (2005) for further details.

post 1978-79 in China, while the percentage share of value added in output of the secondary sector continued to be the highest, it progressively declined from 46% in 1975 to 41.6% in 1990 while the share of services rose to 31.3% in 1990 as compared to 22% in 1975. At the same time, the secondary sectors share in employment grew from 17.4% to 21.4 % in 1990 while that of services grew from 12% in 1978 to 18.9% in 1990 ( table

6).

Table 6: Sectoral shares in GDP and Total Employment

India China

Agriculture, value added

(% of GDP)

Industry, value added

(% of GDP

1983 1990 2003 1975 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005

38.9 31.3 21 32 28 27 20 16.4 13

24.5 27.6 26 46 43 41.6 47 50.2 47

Services, etc., value added

(% of GDP)

36.6 41.1 53 22 18 31.3 33 33.4 40

Employment in agriculture

(% of total employment)

Employment in industry

(% of total

69.1

13.6

59.8

13.7

77.2

13.5

62.4

20.8

53.4

19

52.2

23

46.3

17.3

44.8

23.8 employment)I

Employment in services (% of total

17.3 26.5 9.3 16.8 27.6 24.8 36.4 31.4 employment

Source: World Development Indicators 2006.

(Figures in red are estimates from national accounting sources in case of India)

The value added growth rates were highest for services (12.2%) followed by a 9.5% value added growth rate for Industry during 1980-1990 while the employment elasticities were relatively high at 0.65 and 0.62 for services and industry respectively ( table 7).

Table 7: Rates of growth of output and employment in China, 1980-2000

1980-

90

1990-

2000

Primary sector

Annual employment growth

Annual Value Added growth

Employment elasticity

Secondary sector

Annual employment growth

Annual Value Added growth

Employment elasticity

Tertiary Sector

Annual employment growth

Annual Value Added growth

Employment elasticity

All sectors

Annual employment growth

Annual Value Added growth

Employment elasticity

2.8

6.2

-0.8

3.8

0.45 -0.21

5.9

9.5

0.62 0.12

7.9

12.2

0.65

1.6

13.5

5.1

9.1

0.56

4.1

9.3

1.1

10.1

0.44 0.11

The following decade post WTO accession together with a substantial rise in economic liberalisation and labour market reforms saw changes in this trajectory with

Industry’s share in total value added progressively rising around a trend of 50% during

1990-2005 while that of services declined initially to rise marginally above the 1990 level at 40% in 2005 largely at the cost of a continuously declining share of the primary sector.

The value added growth rates were 12.5% and 8.8% respectively for Industry and services over 1992 -2005 (table 9). China thus had made its transition from agriculture to

Industry in terms of output growth. At the same time, paradoxically employment elasticities of Industry both relative to overall GDP as well as industrial value added growth fell dramatically 23 . Manufacturing employment actually fell at a rate of more than

3% p.a during the latter half of 1990’s when value added growth rates were above 8% p.a ! The figures indicate not merely a structural shift in employment from both agriculture and industry towards services, but also that the impressive growth (9.7%) overall is largely productivity driven rather than employment-led with sectoral employment elasticities not being very high even for services as compared to most other economies within the entire region. At the same time, real manufacturing wages more

23 Other estimates ( Ghose 2005, Chandrasekhar and Ghosh, 2007, UNDP 2006, KILM 2005) also confirm this sharp decline in Industry employment growth rates and elasticities during the 1990’s .

than doubled between 1990 and 2005 further strengthening grounds for belief in an exceptionally high productivity growth in manufacturing ( appendix Table 17a).

Table 8: Employment elasticities and GDP growth (1991-1995, 1995-1999 and 1999-2003)

China

India

Total Employment Elasticity

1992-

1996

0.14

0.4

1996-

2000

0.14

0.43

2000-

2004

0.17

0.36

Average Annual GDP

1992-

1996

Growth (%)

12.7

6.3

1996-

2000

8.3

6.3

2000-

2004

8.1

5.3

Table 9

India

Agriculture

Elasticity

(1992-2005) gdp

China 0.09

Value added

Industry

Elasticity

(1992-2005) gdp Value added

Services

Elasticity

(1992-2005) gdp Value added

Sector value added growth and total growth (1992-2005)

Agriculture Industry Services Total

0.23 0.07 0.06 0.47 0.50 3.7

0.03 0.18 0.20 0.54 0.41 2.8

12.5

6

8.8

8.1

10

6.5

Overall employment growth fell from 4.3% in the 80’s to 1.1% in the 90’s on an average (table 12). The unemployment rate also climbed from 2.5 per cent in 1990 to 3.1 percent in 2000 and 4.3 per cent in 2003 (ILO 2005).

Ghose (2005) further sub divides the period after 80’s into 1990-1995 and 1995-2002 in order to assess the specific impact of labour reforms on employment conditions. Where employment growth rates are concerned, urban employment grew more rapidly than rural employment over the entire period. However, while the period pre 1995 reforms was marked by improvement in employment conditions and the rise of regular employment in both rural and urban areas, the situation worsened considerably afterwards. There was massive labour shedding post the 1995 labour market reforms on part of state and collective enterprises, decline in urban formal and informal wage employment and an increase in irregular employment over the period 1995-2005 ( Ghose 2005). However,

paradoxically in rural areas, the structure of employment saw a rise in regular and formal and informal wage employment and a decline in irregular employment while employment in township and village enterprises continued to grow. Given the fact that overall employment growth in rural areas was actually zero during this period, this merely indicates a structural shift in nature of employment patterns in rural China while all net additions to employment growth were in the urban areas and were brought about by a rise in irregular employment.

India on the other hand has experienced a structural transformation towards services where both value added as well as employment is concerned , though the intersectoral transition from agriculture either to manufacturing or services in the latter case is far from being complete with the primary sector still accounting for almost 60% of the total employment.

The value added shares indicate a shift towards services the share of which grew from

38% in 1983 to 42% in 1994 to more than half of total value added at 53% approx in

2003. At the same time the share of Industry stagnated at about a quarter of total value added fluctuating between 25-27% approx while that of agriculture progressively declined from 37% in 1983 to 21% in 2003 (table 6 ).

Services also experienced the highest average annual value added growth rates during

1992-2005 at 8% followed by Industry with a growth rate of 6% (table 9 ). At the same time while services employment elasticities (0.42) and employment growth was higher, employment elasticities of agriculture as well as overall manufacturing were low during the 1990’s ( 0.01 and 0.29

according to some other estimates

24

). Overall, the late 1990s was a period of quite dramatic deceleration of aggregate employment generation, which fell to the lowest rate recorded level since such data began being collected in the 1950s.

There seems to have been some rise in employment in case of services in the most recent years 25 .

Most estimates

26

confirm the dramatic fall in employment growth and elasticities in case of agriculture during the 90’s, not surprisingly indicating the limits to the

24 Palinivel (2006 ), Kapila (2006), Goldar (2002) , Chandrasekhar and Ghosh (2007) also confirm these trends overall.

25 NSSO , 61 th ROUND, 2004-2005.

26 Kapila (2006), Palinivel (2006), UNDP(2006), KILM (2006).

employment growth potential of the sector. Where manufacturing is concerned, employment growth has stagnated while there has been a substantial rise in labour productivity. According to Goldar (2002), while employment elasticities of organized manufacturing rose slightly from 0.26 in the pre-reform period, 1973-74 to 1989-90, to

0.33 in the post-reform period, 1990-91 to 1997-98, they fell for overall manufacturing given a fall in employment elasticities for unorganized manufacturing which accounts for more than four fifths of the total employment share in manufacturing with growth rates of overall manufacturing employment being as low as 1.87%. At the same , Chandrasekhar and Ghosh point out the sustained increase in labour productivity as measured by the net value added (at constant prices) generated per worker in case of organised manufacturing.

Labour productivity tripled between 1981-82 and 1996-97, stagnated and even slightly declined during the years of the industrial slowdown that set in thereafter, but has once again been rising sharply in the early years of this decade. Where trend in real manufacturing wages are concerned, they point out a corresponding fall in share of wages in value added which declined progressively from the late 1980s till mid 1990s to fall further to half of their mid 1990s level after a brief period of stability. Wages now account for only 15 per cent of value added in organised manufacturing, which is one of the lowest such ratios anywhere in the world. They explain this paradox of rising productivity and falling share of wages in terms of falling employment in manufacturing alongwith stagnating real wages despite a rising trend in output growth which indicates a clear worsening of the bargaining strength of Industrial workers (Chandrasekhar and

Ghosh 2007).

Given the rise of both employment growth as well as value added in services , the nature and level of employment creation in this sector becomes crucial. However, despite

India’s much celebrated success in dynamic software and IT enabled services sector, total employment in this sector as a percentage of total non agricultural employment is insignificant . The rapid rates of growth of the late 1990s were from very small bases, and the sector typically remained very small relative to the rest of the economy, with fewer domestic multiplier effects because of high import dependence . Also, services as a whole is a very heterogeneous sector covering a wide range of activities some of which provide merely a ‘refuge’ employment to those workers not absorbed elsewhere. The

recent rise in services employment in India has been at both high and low value added ends of the services sub-sectors, reflecting both some dynamism and some increase in

“refuge” low productivity employment. We shall look at this sector in greater detail in the next section.

It has also been pointed out widely that there is growing evidence of labour force flexibilisation and informalisation with Indian labour markets being characterised by high degrees of underemployment and underutilisation of labour alongwith rising open unemployment 27 (ILO 2005, ADB 2005). More recently in case of India, evidence seems to suggest a rise in employment as well as in labour force participation rates with the real expansion coming from a substantial rise in estimates for self employment. In this regard, again Chandrasekhar and Ghosh (2007) in a detailed survey of recent employment trends in India and China , indicate that available evidence suggests not only a significant decline in proportions of all forms of wage employment alongwith paradoxically falling or stagnating real wages but also that the latest NSS survey itself indicates the rise in self employment to be largely a distress-driven phenomenon, led by an inability to find adequately gainful paid employment on part of a vast section of the labour force in the current context.

To sum up the discussion here, three broad trends seem to emerge where patterns of growth in output and employment are concerned. Firstly , as compared to the 1980s a fall in average annual as well as sectoral employment growth rates and elasticities alongwith a rise in unemployment rates for both the countries during the 1990’s and the first half of the current decade accompanied the higher rates of growth of output. Secondly , though there has been a structural shift away from the primary sector towards manufacturing in case of China and services in case of India where output growth rates and contributions to total output are concerned, a corresponding shift in terms of employment growth and shares in total employment has not occurred. While manufacturing employment rose during the 1980’s in China, there has been a dramatic fall in employment growth rates during the 1990’s which continues till date with a rising unemployment rate. In case of

India, though employment growth has been sluggish in Industry, some growth at both the high end and low end services has occurred recently but this is yet to transform into a

27 Unemployment rate rose from 2.2 per cent in 1995 to 4.3 per cent in 2000 (ILO 2005).

sectoral transition from employment in low productivity agricultural sector to high productivity, high growth sectors of the economy. Thirdly , the nature of employment in itself has undergone a dramatic change with rising contractualisation, informalisation and flexibilisation of labour force in both these countries with adverse welfare consequences for those at the bottom half.

In case of both India and China , massive labour shedding on part of state owned and public sector enterprises during the decade of the nineties alongwith rising labour productivities in the dynamic high growth sectors of the economy led to these broad outcomes. Srinivasan (2006) dismisses the falling employment elasticities as mere adjustments to shifts in demand and supply conditions which are transitory rather than structural in nature and would rise with an increase in aggregate consumption demand.

However falling employment elasticities to the extent accompanied by a sustained rise in output and labour productivity alongwith changing patterns of output growth seem to indicate certain structural transitions in the growth and employment trajectories of these large surplus labour economies .

While Chandrasekhar and Ghosh (2007) explain the overall decline in the nature and level of employment conditions on the nature of trade liberalisation as well as implementation of domestic privatisation and labour market reforms, others like Ghose

(2005) tend to explain it in terms of the transition to more efficient economic structures brought about by a shedding of surplus labour besides technological changes. To the extent that surplus labour is not absorbed by the growing sectors of the economy, the role of technological change and its impact on demand for labour becomes crucial.

In the following section, in order to correlate changing trade patterns and hence forms of integration with the global economy with the transformation in output and employment patterns, a more disaggregated perspective on existing conditions in the growing manufacturing and services sectors of the two countries is attempted.

Output and Employment growth in Manufacturing and services- A disaggregated perspective

As far as services are concerned, LABORSTA, the ILO database gives disaggregated time series data on employment by economic activity over the period under discussion based on national accounting statistics of both these countries (see tables 18-21 ).

As would be expected on the basis of trends in broad sectoral employment elasticities, there has been a rise in percentage shares of employment in all sub categories in case of services for both the countries. For both the countries, the percentage shares as well growth rates in employment were high in Construction and Wholesale and Retail Trade and Restaurants and Hotels which again is not surprising given our earlier discussion on rise in labour force flexibilisation and informalisation, given that both these sectors are typically refuge sectors with an employment elasticity greater than one . However unlike construction, the latter category given its heterogeneity, also involves a rising employment of more skilled labour with a rise in growth due to greater diversification of economic activities. Community and social and personal services are an important sub sector in case of both the economies both in terms of their share in total services employment as well as their welfare consequences. Their percentage share has been on rise in case of both the countries, but the rise was more accentuated in case of China where their share grew from 2.6% in 1990 to 6% in 2002

28

.

India initially witnessed a marginal rise in this sectors share between 1983-1993 which again fell slightly in 2000. Though the growth rates of employment in this sector actually fell in 1990s as compared to the 80s, the GDP growth rates of this sector too fell as a result of which employment elasticities of growth turned negative

29

. Again as expected on the basis of developing patterns of comparative advantage in trade, employment growth in the services sector exhibits greater dynamism in case of India in case of

Transport, Storage and Communication and Financing, Insurance, real Estate and

Business Services where growth rates rose in the 1990s at higher rates than that prevailing

28 However, there are problems in identification and categorization in case of the Chinese Economy given the command structure of the economy where public provisioning of services is concerned. The rise in percentage share could hence be accounted for merely due to change in classification of these services from activities not adequately defined.

29 This would occur if negative GDP growth is accompanied by negative growth in productivity so that even a small rise in employment growth would turn the elasticity negative. Given that this sector is employment intensive by nature, this trend has adverse welfare consequences implying lower public provisioning of essential services during times of rising unemployment, labour force flexibilisation and informalisation and falling real wages.

in the Chinese economy . However the percentage shares of these sectors in total employment though rising marginally (more so in case of India), still remain very small.

According to the S.P.Gupta committee report, capital intensity of output in case of the

Indian economy rose not only at the aggregate level but also in most sectors including services except in case of these two sub sectors. Hence, the overall decline in the employment elasticity is partly due to the technology impact of labour-capital substitution with rising capital-intensity of output growth occurring even in the small and unorganised sectors and services. The aggregate ICOR has increased from 3.4 during

1991/92-1996/97 to nearly 4.4 in 1996/97 and to over 5.0 during the Ninth Plan.

Where structural transformation and growth in manufacturing sector is concerned, the disaggregated analysis presented here is based on the 3 digit ISIC dataset provided by

World Bank trade and production database

30

. The industries are classified as low skill and technology intensive, medium skill and technology intensive and high skill and technology intensive on the basis of UNCTAD classification

31

. Also, specifically trends in major groups of Industries (in terms of their share in total manufacturing output and employment as well as their increasing importance in rising merchandise trade flows) being analysed here include ‘

Food, Beverages and tobacco’, ‘ Textiles, clothing and leather’, ‘Chemicals , rubber and plastic’, ‘Basic Metals ‘and ‘ Machinery and equipment’.

The analysis here however comes with very strong caveats where employment growth and elasticities is concerned as marked volatility in estimates could arise due to very small changes in underlying variables given the highly disaggregated nature of the data. Also given missing data, the time period covered might not be adequately represented ( tables 23-27).

Where China

32

is concerned the share of low and medium technology intensive industries in total manufacturing output and employment remained high as compared to high technology intensive Industries and was the highest for medium skill and technology intensive Industries. The share of ‘ Food, Beverages and tobacco’, ‘ Textiles, clothing and leather’, ‘Chemicals , rubber and plastic’ and ‘ basic metals ’ in total manufacturing output

30 Nicita A. and M. Olarreaga (2006), Trade, Production and Protection 1976-2004, World Bank Economic

Review 21(1).

31 See appendix note.

32 See tables

remained more or less stagnant or declined slightly while that of ‘ Machinery and equipment’ rose, whereas except for

‘Chemicals

, rubber and plastic’, the share of all these industries in total employment fell. While output growth (ranging from 7%-15%) and productivity was higher in case of all the categories and industry groups being analysed over here in the 90s as compared to the 80s, high technology industries and

‘ Machinery and equipment ’ followed by medium technology industries and chemicals experienced the highest growth in output as well as labour productivity. Despite limitations of the dataset being used here, the trends are in conformity with those expected on the basis of broad sectoral trends in terms of growth in exports, output and employment patterns.

In case of India, again while the share of medium skill and technology intensive

Industries in total manufacturing output was the highest followed by low technology industries, their share in total employment was lower than that of low technology industries. The share of Industrial chemicals in output was highest followed by machinery and equipment while the share of employment was the highest in textiles, clothing and footwear and food , beverages and tobacco . Output and productivity growth both fell in case of low and medium technology industries while employment growth rose marginally in case of low technology Industries but fell substantially for medium technology Industries whose share in total output is the highest. Though output, productivity and employment growth rose in case of high technology industries, their share in manufacturing output and employment remains marginal. Where specific industries are concerned, output growth fell in most categories, in particular for basic metals which also experienced a substantial fall in employment and productivity growth.

Except for machine and equipment , productivity growth fell in most industries while employment growth rates grew marginally. However given the fall in output, employment elasticities would have risen more than proportionately to growth in employment. This gives us a mixed picture overall but does clearly show that the structural transition in terms of its employment effects has been more pronounced in case of China as compared to India.

To sum up, both in case of services as well as manufacturing a preliminary survey of disaggregated data seems to be in conformity with expectations regarding the more

dynamic trading sectors demonstrating greater dynamism and growth in terms of output, productivity and employment indicators. Though adverse employment effects are more pronounced in case of the more aggregated analysis carried out in the earlier section, this could well be a result of limitations in existing data, especially where China is concerned.

Concluding Comments- Directions for further research ?

Some basic facts which emerge from the above discussion and have been discussed in recent literature are the coexistence of rising trade, high rates of growth of output accompanied by disappointingly low rates of growth of employment and labour absorption in case of both India and China despite fundamental differences in their basic economic structures (mixed developing economies vs. a command economy) that continue to influence their differing trajectories in the post reform period.

Several questions become important from whichever perspective one approaches the issue: Is rising unemployment transitional or structural? How long is the time period of adjustment? Are there any path dependent implications? How important are regional and other contextual specificities?

The role of technology remains crucial but the exact mechanism through which it operates is debatable. The argument put forward by the new growth theorists attempts to explain wage inequality and employment effects in terms of a “skill bias” arising out of technology imports to the developing world. As pointed out earlier, to the extent the ‘skill gap’ that arises can be explained in terms of absence of requisite skill, it is transitional and can be overcome with adequate infrastructural and R and D investment. Under such circumstances, persistence of long run unemployment and wage inequalities can only be explained in terms of institutional rigidities and lack of adequate investment which hinder the growth potential of such economies. Given that both the Asian giants (in particular

China) have experienced relatively high levels of investment and also have a relatively elastic supply of skilled labour due to existence of a “ pool of labour with basic skills” these explanations do not seem to provide all the answers. Moreover to explain these phenomenon in terms of institutional rigidities is to merely state how history unfolds itself.

Here India and China given the sheer size of their economies, provide interesting grounds to explore the interaction between domestic structural adjustments and the imposition of production patterns due to integration with global production chains. In keeping with changes observed elsewhere in the developing world, rising trade integration alongwith domestic economic reforms has led to loss of employment and job security in both the countries due to massive labour shedding on part of state-owned enterprises, rising import penetration, as well as macroeconomic fluctuations resulting from short-term capital movements.

At the same time, trade integration combined with delocalization of production and services from the developed world has led to rising trade, production in case of various groups of Industries such as food processing, textiles or garments, Industrial chemicals, office equipment, electronics, and ICT (information & communications technologies). As pointed out earlier, to the extent that surplus labour is not being absorbed by the growing sectors of the economy, the role of technological change and its impact on demand for labour becomes crucial.

The changing structure and growth of employment and the nature of labour market conditions in these developing Asian giants has significant implications for both, the resultant welfare consequences as well as their instrumental role in realising the growth and development potential of developing economies . In both these cases, there exist some differences in the nature of the problem facing India and China which are in turn related to differences in the nature of state intervention, resource base as well as levels of development in the two countries.

As far as welfare effects are concerned, active state intervention in the form of public provisioning of basic amenities and social infrastructure has to some degree counteracted the adverse consequences of the rising informalisation and flexibilisation of the labour force. Real wages too seem to have risen. However the increasing pace of labour market reforms and rising labour force migration under conditions of extreme working poverty

(Li Shi 2006) could aggravate the situation considerably. In India on the other hand, low real wages, absence of substantial public provisioning and basic social infrastructure have further exacerbated the adverse welfare consequences of the worsening employment and working conditions.

However, the preoccupation of this paper has been with the second aspect of these changes which is related to the consequences of the structural transformation being wrought in these labour abundant economies for their specific growth trajectories. Given that agriculture even now accounts for more than half of the labour force in these regions, as compared to less than 5% in developed countries, the process of structural transformation is far from complete and if the prospects of rural population are to improve in the presence of bias towards manufacturing and services in terms of both output and employment growth, then there has to be rapid labour absorption in these sectors largely through migration. To the extent that the trend shows high rates of growth are accompanied by high rates of growth of labour productivity and low employment elasticities, a more cogent explanation of the processes at work is required which explain why the vast reserves of manpower within developing Asia are not tapped by the operation of market forces in the long run.

As discussed earlier, the effects of trade integration in India have been largely one-way and domestic , with the possible exception of services, in the sense of its influencing the rate of GDP growth and the share of trade in domestic GDP, rather than India’s more rapid GDP growth influencing global GDP growth significantly. Also, with a few exceptions the share of traditional and labour and resource intensive exports remained the same in total exports even though output patterns indicate a move towards medium skill and technology production in the recent decade. Manufacturing employment elasticities as well as growth remained low and while there was some employment growth in the dynamic sub sectors of the services economy, most of the employment growth remained concentrated in the low productivity ‘refuge’ sub sectors. Hence, even though, the traditional patterns of merchandise trade have not altered dramatically with growth in trade, they have not led to an increased exploitation of India’s comparative advantage in terms of its vast labour reserves. Infact, almost all sectors of the Indian economy have experienced rising capital intensity of production in the era of increased economic openness 33 .

Where China is concerned, both its integration with the global economy as well as its share in global trade, especially where merchandise exports are concerned have risen and

33 S.P. Gupta committee report, 2002.

have also brought in a shift towards a more technology intensive trading and production structure. This was also accompanied by rising TFPs and capital intensities of production.

At the same time, employment growth and elasticities of the dynamic and growing manufacturing sector in particular have fallen drastically by all accounts.

It is arguable that limits to physical capital accumulation have been reached and realisation of higher productivity gains through intersectoral shifts in labour force is essential to sustain the current growth process in case of the Chinese economy. At the same time, given its sheer size and its growing impact on global economic growth and trade, China is much better placed than India in experimenting with an alternative technological growth trajectory which involves a more efficient utilisation of its abundant labour force. However, as proposed by Patnaik (2007), it seems to have become increasingly caught in a growth paradigm where the pace of its technological (as an imitator rather than innovator) as well as structural change gets interlinked with that prevailing in the advanced capitalist economies.

The success of China’s export drive arises therefore from the fact that she can produce manufactured goods at much lower prices than in the West, even while using the same technologies as are available in the

West and hence does not seem to guarantee a dynamic change in its labour market conditions.

This might be an indication of the existence of structural processes that, given the nature of current growth and development strategies based largely on some variant of the dominant economic orthodoxy, are linked to the course of contemporary global economic integration. The question then arises- are there any processes leading to similar growth trajectories for large developing nations, which as a result of mutually reinforcing influences (export orientation and international technological diffusion), keep pushing even growing economies such as India and China in a direction which involves potential underutilization of its labour reserves?

One way to begin exploring these issues would involve investigating certain crucial hypotheses. Firstly, Is the rise of intra industry trade between the US and the two Asian economies an important channel of technological diffusion for the latter? Are their any similarities in the resultant growth trajectories embarked upon by India and China which go beyond fundamental differences in their economic structure? How and to what extent

is the process of technological diffusion different for the two countries? This would involve estimating international R and D spillover regressions employing a production function approach using import/export shares as bilateral weights to capture the relative importance of foreign Rand D activities on domestic factor productivities. The proxies for estimating trade related R and D effects that have been fruitfully employed in earlier studies and could be used over here include patent citations and applications, royalty fees, licensing fees etc. The empirical tools required for this purpose would entail usage of regression analysis to cross-section and time series data for the last two and a half decades.

At the second level, the relationship between productivity differentials that can be traced to changes in composition of trade flows after the first stage would have to be correlated with employment and wage indicators for the two Asian economies in the post liberalization era. Again since TFP depends on both Y/L and K/L – even if there is TFP growth due to technological diffusion, the neo classical presumption is that K/L would be lower in developing countries because of factor price differences. However there are others ( Findlay1978, Rosenberg 1978, Patnaik ) who contend that there isn't much choice of techniques open to developing nations as their pace of technological and structural change gets increasingly linked to the global economy with rising trade integration. As a result, the Y/L in developing countries (at least in tradeables) converges to Y/L in developed countries . It would be interesting to test these competing hypotheses vis-à-vis the characteristics of the global value added chains emerging as a consequence of rising intra industry trade. This would involve exploring possibilities of examining the cointegration relationship between Y/L in developed and developing countries.

Alternatively one might try to look at responsiveness of K/L in developing countries to domestic factor-price movements--though this will be more difficult as there might not be enough variability in factor prices in the sample and the response would anyway be expected to take place after a long lag. Again differences in logs of labour productivity of developed and developing countries might throw up some interesting results.

As far as wage and price indicators are concerned, it would be interesting to look at wage differentials for the same class of labor between the tradeable and non-tradeable sector. If there is a substantial differential after eliminating composition effects, then it