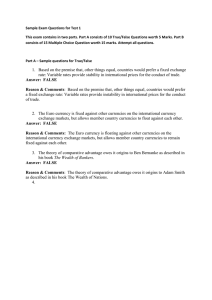

I n T

advertisement