1 Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION

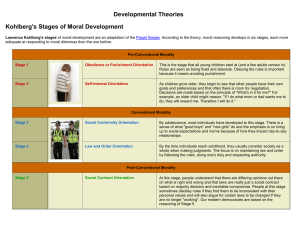

advertisement