CALIFORNIA WATER RIGHTS THEORY: BOTTLING UP THE PUBLIC TRUST

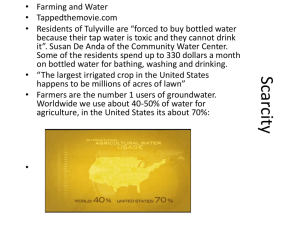

advertisement