1 Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION

advertisement

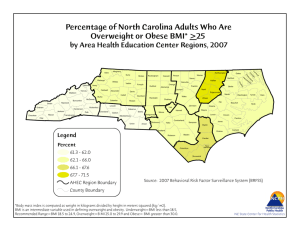

1 Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION Globesity Obesity has been and continues to be a global epidemic with some reports indicating that, worldwide, more than 1 billion adults classify as overweight and 300 million adults are considered clinically obese (Adams & Rini, 2007; World Health Organization, 2003). The predominant tool used for assessing overweight and obesity is body mass index (BMI), which is calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by the square of height in meters (kg/m²). A BMI of 25.0 to 29.9 is considered overweight, 30.0 to 39.9 is obese, and 40.0 or greater is extreme obesity (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009). A limitation to using BMI calculations as a measure of obesity is the inability to distinguish between fat mass and fat-free mass (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009). The increase of lean muscle mass following exercise and strength training may reflect an increase in weight but is not considered to be an unhealthy gain. It is the increase of fat mass that may eventually lead to negative health issues (Hoffman et al., 2006). Despite these limitations, BMI has proven to be a reliable tool in assessing overweight and obesity. Side Effects of Obesity Physical Obesity affects people across gender, racial, and ethnic groups (Sothern & Gordon, 2003) and carries with it numerous negative physical, psychological, and 2 financial consequences. For example, the obese individual is burdened with several health issues and Hensrud and Klein (2006) report that at least one medical comorbidity is associated with roughly three quarters of extreme obesity in adults. Coronary heart disease (Haberman & Luffy, 1998) and type II diabetes (Hoffman et al., 2006) are both major complications associated with obesity. Patrick and Nicklas (2005) also suggest that there is a higher risk of cancer in obese individuals. The rate of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and sleep apnea are also on the rise and are linked to obesity (Hensrud & Klein, 2006; Strauss, 2002). Strauss’s (2002) work lists several physical side effects that are associated with obesity including, but not limited to, hypertension, orthopedic issues, respiratory problems, neurological issues, gastroenterologic side effects, and endocrine problems. Obesity also increases the risk of premature death (Hensrud & Klein, 2006; World Health Organization, 2003). Psychological In company with physical side effects are the psychological consequences of obesity. Research does not implicate a higher level of psychiatric disorders concurrent with obesity, but does propose that individuals with obesity are more psychologically dysfunctional than are normal weight individuals (Hensrud & Klein, 2006). For example, results of correlational studies indicate that obesity is linked to low self-esteem, high rates of depression, high levels of anxiety, and low academic performance (Hensrud & Klein, 2006; Hoffman et al., 2006). These impairments can steer an individual into poor health behavior choices, which perpetuates the cycle of unhealthy weight gain (Bas et al., 2008; Bryant et al., 2007; Desai et al., 2008; Hensrud & Klein, 2006; LaFountaine et al., 2006; 3 Smith et al., 1999; Von Ah et al., 2004). In addition to the direct psychological issues, the obese individual encounters discrimination from medical professionals and society as a whole as he or she deals with everyday challenges. Ward-Smith (2010) suggested that, in spite of the overall tolerance levels that have developed in regard to gender, race, and even sexual orientation, the general public feels it is still socially acceptable to target overweight and obese individuals and treat them with prejudice. Hensrud and Klein (2006) have reported that employers are less likely to hire or promote obese employees and that obese individuals are also less likely to receive wages equal to their normal weight coworkers. Financial Researchers have discovered that the health care costs associated with obesity outweigh costs associated with any other medical condition, including smoking (Hensrud & Klein, 2006) and alcoholism (Ward-Smith, 2010). Costs to employees are increased with obese workers because of absenteeism, and although only 3% of the American work force is extremely obese, 21% of workplace health care costs are associated with extreme obesity health issues (Hensrud & Klein, 2006). Sothern and Gordon (2003) report that the cost of health-care issues with obese adults was 45.8 billion dollars at the time of their research. Ward-Smith (2010) points out that the U.S. spent an estimated $117 billion on overweight and obese individuals in the year 2000. The physical, psychological, and financial impacts associated with overweight and obesity are staggering and affect not only the overweight and obese individual, but also family, friends, and co-workers, and general public. 4 Genetics vs. Environment In an attempt to understand overweight and obesity, many researchers, including Eppstein and Cluss (1986), acknowledge that even with a high percentage of genetic influence, it is the combination of genetic predisposition and environmental factors that influences obesity. To examine the relation between genetics and environment, Eiben and Lissner (2006) conducted a study consisting of adult females (ages 18-28 with a BMI of at least 18.5) with at least one obese parent. Over the course of one year, the intervention group had access to literature and counseling on the topics of physical activity, diet, and weight control, while the control group did not have access to these resources. The results of the study reveal significant differences between the intervention group and the control group in changes in body weight, BMI, and self-reported level of physical activity. These findings are important in that they demonstrate the ability to decrease or maintain healthy weight in the presence of genetic predisposition for obesity. Another focus of the genetic relation with obesity is on biological cues within overweight and obese individuals and whether or not there are differences in comparison to normal weight individuals. Some obese individuals report that they do not receive satiety signals from their body, which has led to research on the subject of biological sensations (i.e., hunger and fullness) and their impact on eating behavior (Barkeling et al., 2007). Barkeling and colleagues found that, even when obese individuals initially selfreport that their eating behavior is not altered by sensations of hunger and fullness, when participating in an experimental laboratory setting these bodily sensations were clearly detected and reported by the obese individuals. Results from studies such as these suggest 5 that, even though genetics maintain some influence in the battle of obesity, weight management can be successful through modification of environmental factors. The observation that obesity rates have doubled over the last two decades further supports the argument that environmental influences play a significant role in obesity development. Currently society fosters an obesigenic lifestyle, which is an environment that promotes weight gain and is not conducive to losing weight (Hensrud & Klein, 2006; McGuire et al., 2001; Mohindra et al., 2009; Sothern & Gordon, 2003). Accessibility, cost, and portions of fast food, “ready to eat” meals, and processed foods are examples of our current obesigenic environment that contributes to poor food choices and ultimately perpetuates overweight and obesity (Ball & Crawford, 2006; Hensrud & Klein, 2006; Mohindra et al., 2009; Young & Nestle, 2002). The emergence and power of environmental influences are of great interest due to their modifiability towards healthier behavior choices. Obesity in Young Adults To date, there has been an abundance of research on obesity and overweight in children and adults, but unfortunately the transitional age of young adulthood has not received as much attention. Young adulthood is traditionally regarded as a healthy and vibrant period of life, perhaps contributing to the shortage of focus on overweight and obesity within this group. Reports, however, are beginning to reveal an alarming trend across the globe: some of the highest increases in the prevalence of overweight and obesity are being seen among young adults. For example, between 1990 and 2000, the largest increase in obesity in the United States (U.S.) was discovered in the 18 to 29 year 6 age group (Hensrud & Klein, 2006). Similar trends have been reported in Sweden (Eiben & Lissner, 2006), the Netherlands (Kemper el al., 1999), and Australia (Wayne et al., 2010). This is problematic because research demonstrates that a person who is obese or develops obesity in young adulthood is at an increased risk of remaining obese through adulthood (Desai et al., 2008). Why are Young Adults at Risk? Risky Behavior It is during young adulthood that research has unveiled a high rate of participation in unhealthy and risky behaviors, including behaviors that impact weight (Adams & Rini, 2007; Brunt et al., 2008; Buckworth & Nigg, 2004; Hoffman et al., 2006; Mohindra et al., 2009; Nelson et al., 2008). Health behaviors that are found to contribute to overweight and obesity are alcohol consumption, caffeine consumption, overeating, eating less healthy and nutritious foods, eating a small variety of foods, frequent snacking on nonnutritional food, and consuming foods higher in sugar, sodium, and fat (Adams & Rini, 2007; Brunt et al., 2008; Von Ah et al., 2004). It is also noteworthy to consider the new environment and use of unhealthy methods of weight loss and management by many young adults and their contributions to health and weight problems. As young adults are faced with new life demands, they experience higher levels of stress, which contribute to weight gain (Brunt et al., 2008; LaFountaine et al., 2006; Von Ah et al., 2004). In an attempt to lose or manage weight, some young adults adopt risky health behaviors such as skipping meals, the use of laxatives after eating, vomiting after food consumption, and substance use (Bas et al., 7 2008; Malinauskas et al., 2006; Nelson et al., 2008). These are all examples of eating and health behaviors that contribute to overweight and obesity and, as with other behaviors, can be modified towards healthier behaviors. Eating Behavior An extensive amount of research has been conducted to examine an individual's eating behavior and it's relation to body weight, and various inventories and surveys have been developed to assess different eating styles and behaviors in individuals. The three predominant eating styles that have been identified are restraint, disinhibition, and hunger (Bas et al., 2008; Bryant et al., 2007; Drapeau et al., 2003; Foster et al., 1998; Ganley, 1988; McGuire et al., 2001). Research (described below) attempts to identify a link between eating behavior and weight as a potential means of predicting weight fluctuations and susceptibility to weight modification (Bas et al., 2008; Bjorvell et al., 1986; Bryant et al., 2007; Drapeau et al., 2003; Dykes et al., 2004; Foster et al., 1998; Ouwens et al., 2003). Restraint Restraint refers to behaviors and eating strategies that are used to limit the intake of food and to control overeating. Examples include avoiding low- nutrient foods (such as foods higher in sugar, salt, and/or fat), reducing portion size, and ceasing eating when feelings of fullness are initially detected (Bryant et al., 2007). Higher restraint is associated with lower body weight, lower BMI, lower consumption of calories from sweets or fats, higher use of fat-reducing behaviors in food preparation and choices, decreased energy intake, and an increase in physical activity (Drapeau et al., 2003; 8 McGuire et al., 2001). Herman and Mack have conducted extensive research on restrained and unrestrained eating. In one study, they compared the eating behavior of female college students after manipulation of an external restraint factor (Herman & Mack, 1975). The participants of this study were divided into 3 groups, each consisting of 15 normal weight and 4 obese participants, and asked to do a tasting of ice cream following a milkshake preload: group one received no preload, participants in group two were asked to drink one 75-oz milkshake prior to the ice cream tasting, and group three subjects were asked to consume two 75-oz milkshakes prior to the tasting. All participants were then asked to taste and rate three pint-sized cups of ice cream and were invited to consume as much of their servings as they would like. Herman and Mack (1975) discovered that, regardless of weight, high restraint participants tended to consume more ice cream following either a one- or two-milkshake preload than participants with no preload at all. Low restraint participants were observed to consume less ice cream following a preload. These researchers also found that, although the difference was not statistically significant, obese participants displayed more overall restraint. In this experiment, Herman and Mack (1975) were investigating the theory that individuals have different biological set-points that may interact with their restraint levels. Consistent with predictions, they found that normal-weight individuals with a consistently high and strict restraint level may have a lower set-point for hunger and, therefore, may consume more (overeat) when external restraint has been manipulated (i.e., with a milkshake preload). Their results support the theory that overeating occurs in 9 all weight categories and that restraint might explain eating behavior (rather than overeating resulting from the state of being overweight or obese). Ouwens et al. (2003) have conducted a similar preload experiment and reveal comparable results to Herman and Mack (1975). Their findings indicate that, regardless of current weight, restraint is not an exclusive predictor of food consumption following a preload. Ouwens et al. (2003) found that amount of food consumed following a preload was an effect of a participant's tendency to overeat (disinhibition) in both high and low restraint participants, supporting the findings that individuals have varying levels of a tendency to overeat, regardless of current weight and level of restraint. Disinhibition Disinhibition refers to eating behavior in relation to an obesigenic environment and includes behaviors like emotional eating, over-eating in the presence of others who are eating, or eating because of the enjoyment of food with disregard to feelings of fullness (Bryant et al., 2007). Research has repeatedly demonstrated that high disinhibition scores are related to increased body weight, higher BMI, more weight fluctuations, lower physical activity levels, and dietary relapse (Barkeling et al., 2007; Bryant et al., 2007; Drapeau et al., 2003). Studies have also demonstrated that higher disinhibition scores are related to food selections that are high in fat, sugar, and sodium, and that people with higher disinhibition select more processed foods and “sweet” food and beverages and have higher alcohol and chocolate consumption (Bryant et al., 2007). Bjorvell et al. (1986) and Bryant et al. (2007) have also discovered that obese and overweight individuals tend to score higher on disinhibition questions than do their 10 normal-weight counterparts. The disinhibition factor not only plays a significant role in overweight and obesity, but it may also be related to dietary failure (Bas et al., 2008). Hunger Hunger is the extent to which biological sensations of hunger are detected and how that influences food intake (Bryant et al., 2007). Examples of hunger include feeling so hungry that food consumption occurs more than three times a day or that feelings of satiety are difficult to achieve. Boschi et al. (2001) have discovered that obese women in a weight reduction program scored higher on the hunger scale than normal-weight women, but similar to overweight women. Barkeling et al. (2007) have discovered that obese individuals experience differences in biological sensations of hunger and fullness, which may lead to overeating by some overweight and obese individuals. Even with such findings, these researchers discovered that with the consumption of a laboratory meal, all participants were able to detect their biological signals of fullness, suggesting that the capacity to “read” their signals is present and can be a point of focus in treatment for overweight and obesity. It seems as though the relation between hunger scores and body weight is still unclear, as some research reveals that a higher score on the hunger scale is associated with a higher energy intake, weight, and BMI (Dykes et al., 2004). Interestingly, however, many other researchers do not find a correlation between BMI and hunger scores (Bas et al., 2008; Boschi et al., 2001; Foster et al., 1998). Research with obese individuals who have received weight loss treatment reveals that hunger did not play a role in weight-reduction among this population and that their administered weight 11 reduction treatment did not affect hunger scores, suggesting that attempts at weight reduction may benefit by including treatment in dealing with hunger on a more personal and emotional level (Bjorvell et al., 1986). Combinations of the Factors Studies have also examined restraint, disinhibition, and hunger and their relation to each other when studying eating patterns and weight. Research suggests that the relation between disinhibition and weight is weakened when an individual scores high in disinhibition and high in restraint (Bryant et al.. 2007; Dykes et al.,2004; Ganley, 1988). For example, when a person eats more in the presence of others but also attempts to count calories, the result will be no significant weight change because the increased consumption is paired with the control over the food consumed. These research groups also find that individuals who tend to eat more in the presence of others or ignore body cues of satiety (a high score in disinhibition) and choose less nutritional food or larger portions than necessary (a low score in restraint) have a higher body weight, as do those who score high in disinhibition and high in hunger (the physical sensation that they can not reach satiety). Drapeau et al. (2003) discuss findings of a longitudinal study that indicate a relation between weight loss, exerted control over food quality and quantity (high restraint score), and low frequency of emotional eating (low disinhibition score). Foster et al. (1998) support this finding with research that indicates that larger weight loss is associated with increases in restraint and decreases in maladaptive weight controlling behaviors. McGuire et al., 2001 demonstrate that as restraint increases, body weight 12 decreases and weight-controlling behaviors increase. This result is important to consider when evaluating treatment for overweight and obese individuals and these researchers suggest that scores on the restraint factor may play a role in an individual's adherence to behavioral changes in eating behavior. Bas et al. (2008) have discovered that high scores in all three of the eating behavior categories are associated with low self-esteem, anxiety regarding social physique, and dieting behavior. When attempting to modify and maintain health behavior changes, it is important to consider the relationships between the eating behaviors and how their interactions may influence an individual’s ability to change. Social Support Social support has repeatedly demonstrated positive effects on young adults and their health behaviors (Gruber, 2008; Verheijden et al., 2005; Von ah et al., 2004). Many self-change groups have modeled interventions after these findings by providing support groups in which individuals develop and maintain friendships with other members who are working toward the same self-change goal, such as weight-reduction groups (Gruber, 2008, Verheijden et al., 2005). Social support is defined as both the availability of others (family, friends, peers, and co-workers) and as the perception of support received (regardless of the actual amount received) by others in an individual's life (Verheijden et al., 2005). Blanchard et al. (2005) have investigated the social and ecological determinants of overweight and obesity and their results reveal that social support is a positive predictor of physical activity across all three body weight categories (normal, overweight, 13 and obese). Researchers are also interested in examining which types of social support have the strongest influence when it comes to health behaviors. While support from both peers and friends are beneficial to an individual, Gruber (2008) demonstrates that the support from friends has slightly more influence than from peers alone for young adults. Ball and Crawford (2006) have also discovered that when an individual receives encouragement from a friend in regards to physical activity, she tends to gain less weight. When social support from family was compared with friends, support of both healthy eating and physical activity was more frequently received from family members than from friends (Ball & Crawford, 2006). However, an individual's level of family social support was positively correlated with that individual’s BMI (Ball & Crawford, 2006), which they suggest may be due to the individual’s level of autonomy and self-motivation for weight loss rather than their need for outside support. Studies conducted by Gruber (2008) and McNeill et al. (2006) support findings that when individuals receive positive support regarding different health behaviors, they are more likely to experience higher levels of motivation to carry out those behaviors. Although social support has proven to be influential in promoting weight loss behaviors for the majority of individuals, females have a higher perceived amount of social supports from friends and from peers, which includes a combination of encouragement and criticism of eating and exercising behaviors (Gruber, 2008). More important than individual research findings, the fact that social support in any degree and from any source plays a role in health behavior change should remain a focus and continue to be investigated when searching for effective treatments for 14 overweight and obesity. As health professionals move forward with treatment for overweight and obese patients, it is important to examine and understand the positive role of social support, which source of social support will be most effective for each individual, and how to maintain positive health behaviors via internal motivation (McNeill et al., 2006; Verheijden et al., 2005). Physical Activity Strongly linked to overweight and obesity is physical activity, particularly participation in sedentary behaviors. Since weight gain occurs when there is an energy imbalance and individuals are taking in more calories than they are expending, an individual's level of physical activity will play an important role in achieving and maintaining a healthy body weight. Although much of the research conducted on the young adult age group has focused on dietary intake as the main contributor to weight gain, attention to physical activity is increasing. For example, Butler et al. (2004) found that weight gain in first-year college female students was not a result of increased caloric intake, but a result of a decrease in physical activity. For both genders there was actually a decline in energy and fat intake during this stage of life. One reason for the decline in physical activity is that college students are faced with academic time demands that obligate them to participate in more sedentary activities, like sitting in class, reading, and studying (Buckworth & Nigg, 2004). Although male students maintain a higher level of physical activity than females while in college, Buckworth and Nigg (2004), state that men report more time engaged in sedentary behaviors than women. Research by Mohindra et al. (2009) indicates that 15 increased sedentary behavior also leads to changes in an individual's consumption of food and beverage, which further complicates the issue. Objectified Body Consciousness Another factor that research has linked to overall well-being and health is body experience, which is related to a person's overall mental, emotional, and physical experience of her body (McKinley &Hyde, 1996). Different elements influence an individual's body experience which result in either a positive or negative experience. The theory of objectified body consciousness (OBC) proposed by McKinley and Hyde (1996) states that cultural expectations of beauty and physical appeal have created the belief that the female body is an object, leading a woman to separate her body parts from her identity and to then view her body as if she were an outsider. Once a woman has internalized these expectations she begins to view these beliefs as if they are her own, rather than as an outside influence, which leads to more shame if she is unable to live up to these standards. Sinclair and Myers (2004) point out that the internalization of cultural standards of beauty influences a person's overall body experience and that a negative body experience has been associated with detrimental health behaviors (i.e., disordered eating) as well as negative emotional issues (i.e., low self-esteem, depression). Research implies that negative body image and body experience is more prevalent in women than men (McKinley & Hyde, 1996). Three components of OBC have been identified: body surveillance (constant monitoring of how one's body looks to others), shame (internalization of the cultural standards), and appearance control (the belief that one's appearance can be controlled; McKinley & Hyde, 1996; Sinclair & Myers, 2004). 16 Research suggests that body surveillance and shame are associated with a negative overall body experience while appearance control is associated with a positive body experience (McKinley & Hyde, 1996; Sinclair & Myers, 2004). Hypothesis Young adults are at greater risk now for overweight and obesity than ever before, which may be attributed to the drastic changes in their living and social environments. Abundant amounts of research imply that this age group is amenable to changes in health behaviors and that the sooner any change is initiated, the better chance an individual has for long-term success. Thus, I focused on the modifiable lifestyle factors of eating behavior, social support, physical activity, and body consciousness in my thesis research. I hypothesized that higher BMI scores will be observed in individuals with low restraint scores, high disinhibition scores, low social support, low physical activity levels, and low appearance control beliefs. 17 Chapter 2 METHOD Participants With approval from the California State University, Sacramento (CSUS) Psychology Department's Human Subjects Committee, students enrolled in lower division Psychology courses at California State University, Sacramento during the Spring 2012 semester were recruited for this research. A power analysis using an alpha level of .05 and an effect size of .80 determined that 131 participants would be sufficient for this study. A total of 280 students participated in this study, turning in 269 fully completed, usable survey packets. In this study, 77.6% of the participants were female and 22.4% were male. The age range was 34 years, with a minimum age of 18 and a maximum of 52 (M = 21.5, SD = 5.01). About half of the participants were in their Freshman (21.7%) or Sophomore (29.2%) year with the remaining participants at the Junior and Senior levels, and only .7% were at the Graduate/Post Baccalaureate level. Based on height and weight, I calculated BMI and found the mean BMI was 24.29 (considered normal weight), the lowest BMI reported was 16.0 (considered underweight) and the highest was 52.4 (considered obese). When examining the BMI classifications, 6% of the participants fell into the underweight classification, 57.7% were considered normal weight, 23.1% were overweight, and 12.1% fell into the obese classification. 18 Materials Participants completed a survey packet which included a demographic sheet, the Three Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ), a Social Support and Eating Habits Survey, a Social Support and Exercise Survey, a Physical Frequency Activity survey, and the Objectified Body Consciousness (OBC) Scale. The demographic sheet collected information including age, gender, ethnicity, income, year in college, height of participant, and weight of participant. Latin square counter-balancing was used when preparing each of the surveys within each packet to limit any order effects while the demographic sheet was always placed at the end of the packet. The TFEQ, created by Stunkard and Messick (1985), is a 51-item, 2-part questionnaire that measured three different aspects of eating behavior: restraint (Factor I), disinhibition (Factor II), and hunger (Factor III). The restraint factor was calculated by 21 items, disinhibition by 16 items, and hunger with 14 items. Thirty-six questions required a true/false response (Part 1) and fifteen questions were answered using a 4-point response scale (Part 2; each question has different response anchors). In scoring for Part 1, one point was given for each answer that reflected a match to the eating factor being assessed. Although Part 2 utilized a 4-point response scale, responses were dichotomized. Responses were split at the middle, with answer choices 1 and 2 scored as 0 points and answer choices 3 and 4 scored as 1 point, with the exception of one item that was reversecoded. Higher scores for each factor indicated a higher presence of that eating behavior in the individual surveyed. Sample questions that measured restrained eating were, “I deliberately take small 19 helpings as a means of controlling my weight” (True = 1 point), “I enjoy eating too much to spoil it by counting calories or watching my weight” (False = 1 point), and “How conscious are you of what you are eating” (Not at All and Slightly responses = 0 points, Moderately and Extremely responses = 1 point). Examples of disinhibition items were, “I usually eat too much at social occasions, like parties and picnics” (True = 1 point), “It is not difficult for me to leave something on my plate” (False = 1 point), and “Do you go on eating binges though you are not hungry?” (Never and Rarely responses = 0 points, Sometimes and At Least Once a Week responses = 1 point). Sample hunger questions were “I sometimes get very hungry late in the evening or at night” (True = 1 point), “I often feel so hungry that I just have to eat something” (True = 1 point), and “How difficult would it be for you to stop eating halfway through dinner and not eat for the next four hours?” (Easy and Slightly difficult responses = 0 points, Moderately difficult and Very difficult responses = 1 point). Stunkard and Messick (1985) reported a coefficient alpha reliability value of 0.92 for Factor I, 0.91 for Factor II, and 0.85 for Factor III. The Social Support and Eating Habits Survey and the Social Support and Exercise Survey (Sallis et al., 1987) was designed to measure an individual's social support and strain received from family (defined as anyone living in the same household) and friends (defined as friends, acquaintances, and coworkers). These surveys can be administered separately or together, with 10 items in the Eating Habits Survey and 13 items included in the Exercise Survey. Both parts of the survey were answered according to a 6-point scale, with 1 meaning “none,” 3 meaning “a few times,” 5 meaning “very often,” and 8 meaning “not applicable.” Examples from the Eating Habits Survey included 20 “Encouraged me not to eat 'unhealthy foods' (cake, salted chips) when I'm tempted to do so” (support) and “Brought home foods I'm trying not to eat” (strain). Examples from the Exercise Survey included “Gave me encouragement to stick with my exercise program” (support) and “Complained about the time I spend exercising” (strain). Scores for the Eating Habits Survey were calculated separately for family and friends. For the purpose of this study, the scores attained were individually summed and averaged to assess six constructs: support from family and support from friends in relation to eating behavior and exercise and discouragement from family and discouragement from friends in relation to eating behavior. Sallis et al. (1987) reported a coefficient alpha reliability value of .87 for positive support of eating behavior from both friends and family, .84 for positive support for exercise from friends, and .91 for positive support for exercise from family. The Physical Activity Frequency questionnaire is a 9-item survey that assessed an individual's participation in vigorous, moderate, and light physical activity at work, at home, and during leisure time. Answers were provided using a 6-point scale (0 = never, 3 = several times a month, and 5 = several times a week) and indicated an individual's frequency of physical activity. Scores were averaged to determine how frequently an individual participated in physical activity, with a higher score reflecting more frequent participation. The Objectified Body Consciousness Scale (McKinley & Hyde, 1996) was designed to measure body surveillance, shame, and appearance control. This study utilized the abbreviated, 14-item version of the survey and responses were provided using 21 a 7-point scale, with 1 indicating “strongly disagree” and 7 indicating “strongly agree.” Sample questions that measured body surveillance were “I often compare how I look with how other people look” and “I often worry about whether the clothes I am wearing make me look good.” Examples of shame questions were “I feel like I must be a bad person when I don't look as good as I could” and “When I'm not the size I think I should be, I feel ashamed.” Appearance control sample questions included “I think I am pretty much stuck with the looks I was born with” and “I think my weight is mostly determined by the genes I was born with.” Scores within each scale were averaged, and two appearance control items were reverse-coded. A higher score in the surveillance and shame components indicated a negative body experience while a higher score in appearance control indicated a positive body experience. McKinley and Hyde (1996) reported a coefficient alpha reliability value of .89 for body surveillance, .75 for shame, and .72 for appearance control. Procedure The researcher met with participants on campus in a reserved room in the Psychology building and provided a consent form to be signed prior to participation in the research. The identity of each participant remained confidential throughout this research. The researcher verbally explained the instructions for completing the demographic sheet and each of the surveys. The researcher then handed out the sheet and questionnaires. Instructions for completing the sheet and the surveys were printed on each of the forms. The participants had thirty minutes to complete the demographic sheet and questionnaires and were given a verbal and written debriefing upon completion of 22 their participation. Each student was credited .5 points toward his or her research requirement for his or her participation in this study. Analysis I examined the relations between overweight/obesity and each of the eating behavior factors, social support for health behaviors, physical activity levels, and objectified body consciousness. Regression analysis was used to examine the hypothesis that obesity and overweight would be observed in individuals with low restraint scores, high disinhibition scores, low physical activity levels, low social support, and low appearance control. 23 Chapter 3 RESULTS First, exploratory analyses were conducted on all variables to ensure normality of the distribution and reliability of measures. All measures were normally distributed and reliable. After that, zero-order correlations between all variables were calculated and examined (see Table 1). A hierarchical multiple regression analysis was used to examine the multivariate relationship between demographic variables, eating behaviors, social support in regard to eating and exercising, physical activity, and body consciousness and their relationship to body mass index (BMI). Variables explained 24.1% of the total variance in BMI in this regression analysis (19% Adj. R²), F(17, 251) = 4.70, p < .001, as shown in Table 2. Age and gender were the demographic variables associated with BMI, such that a higher age was related to a higher BMI (β = .15, p = .01) and being male was related to a lower BMI (β = -.13, p = .03). Disinhibition was the only eating variable associated with BMI, such that higher disinhibition was related to higher BMI (β = .25, p < .001). Of the social support variables, only higher social support of eating behavior from family members was related to higher BMI (β = .17, p = .03). A positive relationship between the body consciousness measure of shame and BMI was also demonstrated, as higher shame was related to a higher BMI (β = .26, p < .001). See Table 2. Table 1. Correlation Table 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 1 Age - 2 Gend -.03 - 3 Rest .02 .02 - 4 Disin .11 .08 .10 - 5 Hung -.06 -.11 -.15 .53 - 6 SEFa -.13 .09 .39 .21 .06 - 7 SEFr -.02 -.03 .29 .09 .04 .42 - 8 SXFa -.04 .08 .24 .02 .02 .45 .18 - 9 SXFr -.07 -.12 .21 -.09 -.10 .19 .40 .37 - 10 StEFa -.01 -.01 .31 .30 .21 .29 .30 .04 .13 - 11 StEFr -.14 -.01 .34 .16 .13 .48 .40 .23 .23 .64 - 12 Surv -.09 .13 .32 .27 .15 .24 .16 .15 .14 .25 .25 - 13 Sha .02 .01 .32 .36 .23 .34 .22 .10 .07 .30 .31 .51 14 Cont .04 -.04 -.11 .10 .18 -.08 -.01 -.06 -.14 .01 .04 -.07 .24 - 15 ViPA -.06 -.15 .26 -.05 -.06 .12 .11 .19 .31 .03 .15 .05 .02 -.14 - 16 MoPA .03 -.08 .21 -.05 -.12 .05 .09 .13 .21 .14 .19 .08 -.01 -.17 .53 - 17 LtPA .03 .13 .11 -.01 -.10 .06 .03 .14 .09 .09 .14 .22 .00 -.13 .19 .43 - 18 BMI .18 -.12 .08 .31 .19 .16 .02 .08 .16 .09 .13 .32 .01 .02 .05 .01 .11 18 - - 24 Note. Boldface = p < .05; Gend = Gender; Rest = Restraint; Disin = Disinhibited; Hung = Hunger; SEFa = Support of Eating from Family; SEFr = Support of Eating from Friends; SXFa = Support of Exercise from Family; SXFr = Support of Exercise from Friends; StEFa = Strain in Eating from Family; StEFr = Strain in Eating from Friends; Surv = Surveillance; Sha = Shame; Cont = Control; ViPA = Vigorous Physical Activity; MoPA = Moderate Physical Activity; LtPA = Light Physical Activity; BMI = Body Mass Index. 25 26 Table 2 Hierarchical Multiple Regression Analysis Predicting Body Mass Index Variable B SE β Age .15 .06 .15* Gender -1.53 .71 -.13* Restraint -1.90 1.48 -.09 Disinhibition 6.22 1.74 .25* Hunger -1.14 1.58 -.05 SEFa .79 .35 .17* SEFr .30 .39 .05 SXFa -.26 .34 -.05 SXFr .28 .33 .06 StEFa .31 .41 .06 StEFr -.60 .44 -.11 Surv -.19 .24 -.06 Sha .86 .25 .26* Cont -.23 .28 -.05 ViPA -.08 .26 -.02 MoPA .24 .29 .06 LtPA .14 .28 .03 Note. * p < .05. Total R² = .24 (Adj. R² = .19). F(17, 251) = 4.70, p < .001. 27 Chapter 4 DISCUSSION The purpose of this study was to investigate the relationship between eating behaviors, social support, physical activity, objectified body consciousness, and BMI among young adults. Age and BMI Of the demographic variables examined, and congruent with previous research, results from this study indicate that a higher age is a predictor of higher BMI. Within this particular study, the mean age was 21.5 years, with the maximum age of 52 years. It's possible that, due to 11.2% of the participants being above 25 years, the mean age was higher in my study than in similar research that also has also utilized the college population. When examining the positive relationship between age and BMI, potential reasons may be the sudden and dramatic lifestyle changes experienced by young adults. Many young adults move away from home and no longer have access to the variety of food choices or controlled eating environments that they may have had when living at home. Along with environmental changes, this age group faces new financial responsibilities, increased time and task demands, and more time spent in sedentary behaviors which all may increase the likelihood of skipping meals and consumption of less nutrient-dense foods and eventually a higher BMI (Brunt et al., 2008; Buckworth & Nigg, 2004). During these life transitions, many young adults also experience an increase in stress, which leads to lower physical activity and higher consumption of junk food 28 (LaFountaine et al., 2006). Awareness of the impact that these significant life changes have on young adults and focusing on techniques to reduce perceived stress will be beneficial to assisting this age group in making better life and health choices. With the demonstrated positive relationship between age and BMI, it becomes evident that a focus on health behaviors, stress reduction, and time management among young adults is a necessary step towards fighting obesity later in life. Restraint and BMI In a study examining the differences in eating behaviors among normal weight, overweight, and obese women seeking dietary assistance with weight reduction at a university outpatient clinic, Boschi et al. (2001) discovered a negative correlation between restraint and BMI among normal weight and overweight women. Based on this and additional supportive research (Foster et al., 1998; McGuire et al., 2001), I predicted that individuals with lower restraint would have a higher BMI. However findings from my study did not indicate any relationship between the two factors and therefore did not support my hypothesis. Similar to my findings, Boschi et al. (2001) found that within the control group of normal weight and overweight women (obese women were excluded from the control group), participants who were only seeking nutritional information (not weight reduction) indicated no correlation between restraint and BMI. A possible explanation for these findings is that women who are seeking assistance with body weight reduction may already be employing highly restrained eating behaviors in their continued attempts to lose weight while women who are only seeking to maintain their weight and gain nutritional information exhibit lower restraint. 29 Disinhibition and BMI Similar to previous research, findings from the present study support a positive relationship between disinhibition and BMI, indicating that those who engage in emotional eating, overeating in the presence of others who are eating, and eating without regard to feelings of fullness have a higher BMI. Bryant et al. (2007) demonstrated a relationship between disinhibition and increased food consumption regardless of hunger or restraint. These researchers also discovered a link between high disinhibition scores and a preference for high-fat, high-salt, high-sugar foods, sweet drinks, butter, alcohol, and coffee, among other less nutritional food choices and, as well as a link to a lower intake of fibrous breads, vegetables, and fruit. Bryant et al. (2007) also suggest that higher disinhibition scores increased the likelihood of an individual eating in response to stress, with women at higher risk of that behavior than men. Bryant et al. (2007) found higher disinhibition is predictive of less weight loss, also supported by Bas et al., 2008, after an initially successful diet with obese individuals. Although research has revealed that higher disinhibition scores are predictors of failure of weight management, Drapeau et al. (2003) discovered that a decrease in disinhibition was related to weight loss and better weight management over time. Given this positive relationship between disinhibition and BMI, combined with the information research has provided in terms of high disinhibition and food choices, eating environments, body cues, and physical activity, it becomes evident that education in the areas of nutrition and behavior modification would be valuable for those seeking to achieve and maintain a healthy lifestyle. 30 Social Support and BMI Based on research indicating that social support serves as a strong motivator for healthy eating (Gruber, 2008), I hypothesized that there would be a negative relationship between social support and BMI. In the present study, however, I discovered a positive relationship between social support received from family and BMI, which is also supported by findings by Ball and Crawford (2006). One possible explanation for this may be that, when participating in organized diet and exercise programs, a support system is already in place as a part of that program, whereas the environment of an individual involved in independent diet and exercise does not necessarily have a likeminded support system. While support from both peers and friends are beneficial to an individual, Gruber (2008) demonstrates that the support from friends has slightly more influence than from peers alone for young adults. When social support from family was compared with friends, support of both healthy eating and physical activity was more frequently received from family members than from friends (Ball & Crawford, 2006). Von Ah et al. (2006), however, did not find a relationship between social support and health behaviors. The inconsistencies among results from available research may be due to the way social support was received (health program vs. individual diet and exercise), measured, and - as increased stress has been associated with the adoption of negative health behaviors (Von Ah et al., 2004) - the current level of stress experienced by the participants. Although it is difficult to argue that the presence of social support is detrimental to an individual's success with health behavior changes, it is important to consider whether or not the individual is self-motivated or experiences more success 31 when he receives social support. Physical Activity and BMI As health research has repeatedly suggested, weight gain is more likely to occur when there is an imbalance between energy consumption and energy output (Butler et al., 2004). For this reason, I hypothesized that there would be a negative relationship between physical activity level and BMI. However, the findings from my study did not identify a relationship. A possible explanation for this result is that weight gain is usually the result of multiple factors and the interaction of these factors (i.e., diet, physical health). An individual may report a high level of activity while consuming an exorbitant amount of calories or may be experiencing health issues that are commonly associated with difficulty of weight management (i.e., thyroid, prescription medication). For these reasons, further examination of physical activity together with current physical health and diet will better determine an individual's needs and success with regard to healthy weight management. Results from this study revealed that being male was associated with a lower BMI, which is contrary to findings by Brunt et al. (2008). Buckworth and Nigg (2004) found that women reported lower levels of physical activity while men reported higher levels which may relate to the findings in the present study that males have a lower BMI. With these discoveries, it is natural to point out that the higher physical activity level in men may be assisting with weight management or loss, therefore indicating that physical activity remains vital to overall health and needs to be a continued component of health behavior education and modification. 32 OBC and BMI McKinley and Hyde (1996) note that a sense of appearance control positively contributes to an individual's physical well-being. Similarly, Sinclair and Meyers discovered that a higher presence of appearance control is associated with a person's overall wellness (i.e., nutrition, stress management, self care). In collaboration with these findings, I hypothesized that there would be a negative relationship between appearance control and BMI. However my results did not indicate a relationship between the two. A possible explanation for these findings may be that participants across all BMI classifications acknowledge some level of appearance expectations and may currently exert a certain amount of appearance control. Consistent with research by McKinley and Hyde (1996) and Sinclair and Meyers (2004), results from this study indicated that a higher level of shame is associated with a higher BMI. The positive relationship between shame and BMI suggests that, when working with individuals who are looking to make health changes, it may be advantageous to focus on body image and techniques to modify the internalization of cultural standards of beauty. Limitations As with any research, limitations within this study should be considered. Selfreported physical activity, and height and weight (used to calculate the BMI of each participant) were used due to their practicality. Research has suggested, however, that individuals tend to underestimate their weight, particularly overweight and obese individuals, and tend to overestimate their physical activity (Blanchard et al., 2005; Butler et al., 2004). Though it is acceptable to utilize self-reports, further research or 33 replication might benefit from use of body measurement (i.e. waist measurement, circumference measures, and calipers) or a scale to more accurately assess the current physical weight and pedometers to measure the physical activity of each participant. Another potential limit is the nature of using BMI as the primary tool for classifying each participant's physical status. BMI does not estimate for lean body mass, so it is possible that an athletic body type might get categorized in an inaccurate BMI group. Again, further research would benefit from utilizing measures of body composition in addition to BMI. Considerations This study discusses several long-term health, financial, and psychological sideeffects of obesity and our goal as a society should be to provide education and resources to assist all ages in making smart, healthy choices. A further investigation comparing young adults and older adults may lend itself to a better understanding of this young adult age group. Will changes made in young adulthood carry over into later adulthood? Do young adults adapt to the dramatic lifestyle changes experienced eventually making it easier to implement health behavior changes? The present study also reiterates the importance of addressing health behaviors with young adults to set the course for living a healthy, fit lifestyle. With regard to the role genetics plays in overweight and obesity, it is critical to address the obesigenic environment that young adults are entering while straddled with new financial and time demands. It has been demonstrated that obesity is difficult to reverse and that obesity in young adulthood places an individual at high risk for remaining obese through adulthood 34 (Desai et al., 2008). For this reason, providing tools such as education on nutrition, physical activity, and the role of social support may assist this young adult age group in modifying their lifestyles and making decisions that will prevent the physical, psychological, and financial side effects of obesity and will ultimately assist them in taking control of their physical health. 35 References Adams, R., & Rini, A. (2007). Predicting 1-year change in body mass index among college students. Journal of American College Health, 55, 361-365. doi: 10.3200/JACH.55.6.361-366 Ball, K., & Crawford, D. (2006). An investigation of psychological, social and environmental correlates of obesity and weight gain in young women. International Journal of Obesity, 30, 1240-1249. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803267 Barkeling, B., King, N.A., Näslund, E., & Blundell, J.E. (2007). Characterization of obese individuals who claim to detect no relationship between their eating pattern and sensations of hunger or fullness. International Journal of Obesity, 31, 435-439. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803449 Bas, M., Bozan, N., & Cigerim, N. (2008). Dieting, dietary restraint, and binge eating disorder among overweight adolescents in Turkey. Adolescence, 43,635-648. Björvell, H., Rössner, S., & Stunkard, A. (1986). Obesity, weight loss, and dietary restraint. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 5, 727-734. doi: 10.1002/1098-108X(198605)5:4<727::AID-EAT2260050411>3.0.CO;2-I Blanchard, C.M., McGannon, K.R., Spence, J.C., Rhodes, R.E., Nehl, E., Baker, F., & Bostwick, J. (2005). Social ecological correlates of physical activity in normal weight, overweight, and obese individuals. International Journal of Obesity, 29, 720-726. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802927 36 Boschi, V., Iorio, D., Margiotta, N., D'Orsi, P., & Falconi, C. (2001). The three-factor eating questionnaire in the evaluation of eating behaviour in subjects seeking participation in a dietotherapy programme. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism, 45, 72-77. doi: 10.1159/000046709 Brunt, A., Rhee, Y., & Zhong, L. (2008). Differences in dietary patterns among college students according to body mass index. Journal of American College Health, 56, 629-634. doi: 10.3200/JACH.56.6.629-634 Bryant, E.J., King, N.A., & Blundell, J.E. (2007). Disinhibition: its effects on appetite and weight regulation. Obesity Reviews, 9, 409-419. doi: 10.1111/j.1467789X.2007.00426.x Buckworth, J., & Nigg, C. (2004). Physical activity, exercise, and sedentary behavior in college students. Journal of American College Health, 53, 28-34. doi: 10.3200/JACH.53.1.28-34 Butler, S., Black, D., Blue, C., & Gretebeck, R. (2004). Change in diet, physical activity, and body weight in female college freshman. American Journal of Health Behavior, 28, 24-32. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.28.1.3 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2010). Retrieved October 25, 2010 from http://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/index.html Desai, M., Miller, W., Staples, B., & Bravender, T. (2008). Risk factors associated with overweight and obesity in college students. Journal of American College Health, 57, 109-114. doi: 10.3200/JACH.57.1.109-114 37 Drapeau, V., Provencher, V., Lemieux, S., Després, J-P., Bouchard, C., & Tremblay, A. (2003). Do 6-y changes in eating behaviors predict changes in body weight? Results from the Québec Family Study. International Journal of Obesity, 27, 808-814. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802303 Dykes, J., Brunner, E., Martikainen, P., & Wardle, J. (2004). Socioeconomic gradient in body size and obesity among women: the role of dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger in the Whitehall II study. International Journal of Obesity, 28, 262-268. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802523 Eiben, G., & Lissner, L. (2006). Health Hunters – an investigation to prevent overweight and obesity in young high-risk women. International Journal of Obesity, 30, 691-696. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803167 Epstein, L., & Cluss, P. (1986). Behavioral genetics of childhood obesity. Behavior Therapy, 17, 324-334. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(86)80065-X Foster, G., Wadden, T., Swain, R., Stunkard, A., Platte, P., & Vogt, R. (1998). The Eating Inventory in obese women: clinical correlates and relationship to weight loss. International Journal of Obesity, 22, 778-785. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800659 Ganley, R. (1988). Emotional eating and how it relates to dietary restraint, disinhibition, and perceived hunger. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 7, 635-647. doi: 10.1002/1098-108X(198809)7:5<635::AID-EAT2260070507>3.0.CO;2-K Gruber, K. (2008). Social support for exercise and dietary habits among college students. Adolescence, 43, 557-575. 38 Haberman, S., & Luffey, D. (1998). Weighing in college students' diet and exercise behaviors. Journal of American College Health, 46, 1-6. doi: 10.1080/07448489809595610 Hensrud, D., & Klein, S. (2006). Extreme obesity: a new medical crisis in the United States. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 81, S5-S10. Herman, C., & Mack, D. (1975). Restrained and unrestrained eating. Journal of Personality, 43, 647-660. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.ep8970396 Hoffman, D., Policastro, P., Quick, V., & Lee, S-K. (2006). Changes in body weight and fat mass of men and women in the first year of college: a study of the “freshman 15”. Journal of American College Health, 55, 41-45. doi: 10.1002/eat.20619 Kemper, H., Post, G., Twisk, J., & Van Mechelen, W. (1999). Lifestyle and obesity in adolescence and young adulthood: results from the Amsterdam Growth and Health Longitudinal Study (AGAHLS). International Journal of Obesity, 23, S34-S40. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800881 LaFountaine, J., Neisen, M., & Parsons, R. (2006). Wellness factors in first year college students. American Journal of Health Studies, 21, 214-218. Malinauskas, B., Raedeke, T., Aeby, V., Smith, J., & Dallas, M. (2006). Dieting practices, weight perceptions, and body composition: A comparison of normal weight, overweight, and obese college females. Nutrition Journal, 5, 8 pages. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-5-11 39 McGuire, M., Jeffery, R., French, S., & Hannan, P. (2001). The relationship between restraint and weight and weight-related behaviors among individuals in a community weight gain prevention trial. International Journal of Obesity, 25, 574-580. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801579 McKinley, N., & Hyde, J. (1996). The objectified body consciousness scale. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 20, 181-215. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1996.tb00467.x McNeill, L., Wyrwich, K., Brownson, R., Clark, E., & Kreuter, M. (2006). Individual, social environmental, and physical, environmental influences on physical, activity among black and white adults: a structural equation analysis. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 31, 36-44. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3101_7 Mohindra, N., Nicklas, A., O'Neil, C., Yang, S-J., & Berenson, G. (2009). Eating patterns and overweight status in young adults: the Bogalusa Heart Study. International J ournal of Food Sciences and Nutrition, 60, 14-25. doi: 10.1080/09637480802322095 Nelson, M., Story, M., Larson, N., Neumark-Sztainer, D., & Lytle, L. (2008). Emerging Adulthood and college-ages youth: and overlooked age for weight-related behavior change. Obesity, 16, 2205-2211. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.365 Ouwens, M., Van Strien, T., & Van der Staak, C. (2003). Tendency toward overeating and restraint as predictors of food consumption. Appetite, 40, 291-298. doi: 10.1016/S0195-6663(03)00006-0 40 Patrick, H., & Nicklas, T. (2005). A review of family and social determinants of children's eating patterns and diet quality. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 24, 83-92. Sallis, J., Grossman, R., Pinske, R., Patterson, T., & Nader, P. (1987). The development of scales to measure social support for diet and exercise behaviors. Preventive Medicine, 16, 825-836. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(87)90022-3 Sinclair, S., & Myers, J. (2004). The relationship between objectified body consciousness and wellness in a group of college women. Journal of College Counseling, 7, 150-161. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-1882.2004.tb00246.x Smith, C., O'Neil, P., & Rhodes, S. (1999). Cognitive appraisals of dietary transgressions by obese women: Associations with self-reported eating behavior, depression, and actual weight loss. International Journal of Obesity, 23, 231-237. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800778 Sothern, M., & Gordon, S. (2003). Prevention of obesity in young children: a critical challenge for medical professionals. Clinical Pediatrics, 42, 101-111. doi: 10.1177/000992280304200202 Strauss, R. (2002). Childhood Obesity. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 49, 175201. doi: 10.1016/S0031-3955(03)00114-7 Stunkard, A., & Messick, S. (1985). The three-factor eating questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition, and hunger. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 29, 71-83. 41 Verheijden, M., Bakx, J., Van Weel, C., Koelen, M., & Van Staveren, W. (2005). Role of social support in lifestyle-focused weight management interventions. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 59, S179-S186. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602194 Von Ah, D., Ebert, S., Ngamvitroj, A., Park, N., & Kang, D-H. (2004). Predictors of health behaviours in college students. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 48, 463-474. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03229.x Wane, S., Van Uffelen, J., & Brown, W. (2010). Determinants of weight gain in young women: a review of the literature. Journal of Women's Health, 19, 1327-1340. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1738 Ward-Smith, P. (2010). Obesity – America's health crisis. Urologic Nursing, 30, 242245. World Health Organization (2003). Obesity and overweight. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/media/en/gsfs_obesity.pdf Young, L., & Nestle, M. (2002). The contribution of expanding portion sizes to the US obesity epidemic. American Journal of Public Health, 92, 246-249. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.2.246