THE ROLE OF INTRAVERBAL NAMING ON THE EMERGENCE OF NOVEL

INTRAVERBALS AND EQUIVALENCE CLASSES

A Thesis

Presented to the faculty of the Department of Psychology

California State University, Sacramento

Submitted in partial satisfaction of

the requirements for the degree of

MASTER OF ARTS

in

Psychology

(Applied Behavior Analysis)

by

Monica Lingchi Ma

FALL

2013

© 2013

Monica Lingchi Ma

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

ii

THE ROLE OF INTRAVERBAL NAMING ON THE EMERGENCE OF NOVEL

INTRAVERBALS AND EQUIVALENCE CLASSES

A Thesis

by

Monica Lingchi Ma

Approved by:

__________________________________, Committee Chair

Caio Miguel, Ph.D.

__________________________________, Second Reader

Emily Wickelgren, Ph.D.

__________________________________, Third Reader

Charlotte Carp, Ph.D.

____________________________

Date

iii

Student: Monica Lingchi Ma

I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University

format manual, and that this thesis is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to

be awarded for the thesis.

__________________________, Graduate Coordinator

Jianjian Qin, Ph.D.

Department of Psychology

iv

___________________

Date

Abstract of

THE ROLE OF INTRAVERBAL NAMING ON THE EMERGENCE OF NOVEL

INTRAVERBALS AND EQUIVALENCE CLASSES

by

Monica Lingchi Ma

The purpose of the current studies was to evaluate the effects of teaching unidirectional

intraverbal relations in a statement format on the emergence of symmetry and transitivity

intraverbal relations and equivalence classes. In Experiment 1, eight undergraduates

were exposed to tact training, listener testing, intraverbal training, and a review phase.

Derived relations matching-to-sample (MTS) and intraverbal posttests were presented in

alternating fashion. The two undergraduates in Experiment 2 also passed all the posttests

despite the elimination of the review phase. For Experiment 3, all MTS posttests were

administered before intraverbal posttests and vice versa for four undergraduates. Despite

procedural variations, all fourteen participants met the emergence criteria for derived

relations MTS and intraverbal posttests. Combined results suggest that intraverbal

training may be sufficient for producing novel intraverbal and stimulus-stimulus classes.

Moreover, all participants emitted vocalizations at some point during the last MTS vocal

posttest, suggesting that intraverbal naming mediated responses.

_______________________, Committee Chair

Caio Miguel, Ph.D.

_______________________

Date

v

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My deepest gratitude to the individuals whose ongoing support, advice, and

guidance have helped me achieve this academic and professional milestone:

To Dr. Caio Miguel, for infusing his passion for behavior analysis in me so that I

can become the scientist-practitioner I am today. His commitment as my academic

advisor has helped me immensely in my graduate career and will forever hold me

accountable for conducting research and finding evidence-based interventions.

To my committee members, Dr. Emily Wickelgren and Dr. Charlotte Carp, whose

insightful questions and suggestions, have influenced the development of this study.

To Amanda Chastain, Danielle Hernandez, Adrienne Jennings, Kelli Kent, and

Danika Zias, for conducting and analyzing all research sessions with me in three weeks.

To the cohort that took me under their wing, Sherrene Fu, Sarah Kohlman,

Gregory Lee, Kelly Quah, and Patricia Santos, they have made this academic journey so

memorable with their friendships and endless laughter.

To Preeti Davé, for being a good listener and always being there for me, despite

our distance and super busy schedules.

To Jason Greene, for his continual encouragement, patience, and understanding,

from start to finish.

To my father, mother, and sister, whom I love profoundly and cannot thank

enough for their endless support, love, and all they have done to make me a stronger and

more intelligent woman.

vi

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................... vi

List of Tables ............................................................................................................... x

List of Figures ............................................................................................................. xi

Chapter

1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 1

2. EXPERIMENT 1 ................................................................................................. 17

Method ........................................................................................................... 17

Participants ............................................................................................... 17

Settings and Materials .............................................................................. 18

Response Measurement ........................................................................... 21

Experimental Design ................................................................................ 23

Interobserver Agreement ......................................................................... 26

Treatment Integrity .................................................................................. 27

Procedures ................................................................................................ 28

Results and Discussion .................................................................................. 37

P1 and P2 ................................................................................................. 37

P3 and P4 ................................................................................................. 42

P5 and P6 ................................................................................................. 45

P7 and P8 ................................................................................................. 49

vii

Vocal Posttest and Post-Experimental Interview ..................................... 53

Summary .................................................................................................. 55

3. EXPERIMENT 2 ................................................................................................. 60

Method ........................................................................................................... 60

Participants, Setting and Materials .......................................................... 60

Dependent Measures and Experimental Design ...................................... 60

Procedures ................................................................................................ 60

Results and Discussion ................................................................................... 61

P9 and P10 ............................................................................................... 61

Vocal Posttest and Post-Experimental Interview ..................................... 65

Summary .................................................................................................. 66

4. EXPERIMENT 3 ................................................................................................. 70

Method ........................................................................................................... 70

Participants, Setting and Materials .......................................................... 70

Dependent Measures and Experimental Design ...................................... 70

Procedures ................................................................................................ 71

Results and Discussion .................................................................................. 71

P11 and P12 ............................................................................................. 71

P13 and P14 ............................................................................................. 75

Vocal Posttest and Post-Experimental Interview ..................................... 79

Summary .................................................................................................. 81

5. GENERAL DISCUSSION ................................................................................... 83

viii

Verbal Mediation ............................................................................................ 86

Limitations and Future Research ....................................................................89

Clinical Implications ...................................................................................... 96

Appendix A: MTS Testing and Training Datasheets ................................................. 97

Appendix B: Tact Training and Review Datasheets ................................................ 103

Appendix C: Listener, Testing, Training, and Review Datasheets .......................... 105

Appendix D: AB/BC Intraverbal Training Datasheets ............................................ 107

Appendix E: BA/CB Intraverbal Testing Datasheets .............................................. 109

Appendix F: AC/CA Intraverbal Testing Datasheets .............................................. 111

Appendix G: Remedial Training .............................................................................. 113

Listener Training .............................................................................................. 113

MTS Remedial Training ................................................................................... 113

References ................................................................................................................. 120

ix

LIST OF TABLES

Tables

Page

1. Participant Demographics .................................................................................... 18

2. Target Intraverbal Relations ................................................................................. 20

3. Passing, Mastery, and Emergence Criterion for Each Condition ......................... 26

4. Interobserver Agreement and Treatment Integrity Across Participants ............... 27

5. Pre-Training Target Intraverbal Relations ............................................................ 29

x

LIST OF FIGURES

Figures

Page

1. Experimental stimuli ............................................................................................ 19

2. Sequence of training and testing conditions for P1, P2, P5, and P6 .................... 24

3. Sequence of training and testing conditions for P3, P4, P7, and P8 .................... 25

4. Pre-training stimuli .............................................................................................. 29

5. Results for P1 on top panel and P2 on bottom panel ........................................... 39

6. Response latency in seconds across 18 trials of the first block of each MTS

posttest for P1 ...................................................................................................... 40

7. Response latency in seconds across 18 trials of the first block of each MTS

posttest for P2 ...................................................................................................... 41

8. Results for P3 on top panel and P4 on bottom panel ........................................... 43

9. Response latency in seconds across 18 trials of the first block of each MTS

posttest for P3 ...................................................................................................... 44

10. Response latency in seconds across 18 trials of the first block of each MTS

posttest for P4 ...................................................................................................... 45

11. Results for P5 on top panel and P6 on bottom panel ........................................... 47

12. Response latency in seconds across 18 trials of the first block of each MTS

posttest for P5 ...................................................................................................... 48

13. Response latency in seconds across 18 trials of the first block of each MTS

posttest for P6 ...................................................................................................... 49

14. Results for P7 on top panel and P8 on bottom panel ........................................... 51

xi

15. Response latency in seconds across 18 trials of the first block of each MTS

posttest for P7 ...................................................................................................... 52

16. Response latency in seconds across 18 trials of the first block of each MTS

posttest for P8 ...................................................................................................... 53

17. Sequence of training and testing conditions for P9 and P10 ............................... 61

18. Results for P9 on top panel and P10 on bottom panel ......................................... 62

19. Response latency in seconds across 18 trials of the first block of each MTS

posttest for P9 ...................................................................................................... 63

20. Response latency in seconds across 18 trials of the first block of each MTS

posttest for P10 .................................................................................................... 65

21. Sequence of training and testing conditions for P11 and P12 ............................. 71

22. Sequence of training and testing conditions for P13 and P14 ............................. 71

23. Results for P11 on top panel and P12 bottom panel ............................................ 73

24. Response latency in seconds across 18 trials of the first block of each MTS

posttest for P11 .................................................................................................... 74

25. Response latency in seconds across 18 trials of the first block of each MTS

posttest for P12 .................................................................................................... 75

26. Results for P13 on top panel and P14 on bottom panel ....................................... 77

27. Response latency in seconds across 18 trials of the first block of each MTS

posttest for P13 .................................................................................................... 78

28. Response latency in seconds across 18 trials of the first block of each MTS

posttest for P14 .................................................................................................... 79

xii

1

Chapter 1

INTRODUCTION

The formation of equivalence classes has served as a behavior analytic model for

understanding symbolic behavior and the emergence of novel behaviors (Sidman, 1994;

2009). In his seminal study, Sidman (1971) taught an intellectually disabled adolescent

two relations among three classes of stimuli – dictated words (A), pictures (B), and

printed words (C) – via a matching-to-sample (MTS) conditional discrimination

procedure. Within the MTS procedure, the participant was instructed to select a picture

(B) or printed word (C) from an eight stimuli array (i.e., visual comparison stimuli),

conditional upon a dictated word (A; i.e., an auditory sample stimulus) presented by the

experimenter. This arrangement of stimuli presentation is known as auditory-visual

MTS. After mastering these two relations (AB and AC), the participant was then able to

select printed words in the presence of corresponding pictures (BC), and to select pictures

in the presence of corresponding printed words (CB). As a result of this teaching

procedure, the ordered pairs (AB and AC) of stimuli became equivalent and substitutable

for one another. In other words, they acquired the same “meaning.” Sidman and Tailby

(1982) later coined the emergence of CB and BC relations given AB and AC training as

transitivity. If the AB and AC relations were trained via visual-visual MTS (e.g., in the

presence of a printed word as the sample, selecting a picture from the comparison array),

then and the derivation of BA and CA relations are known as symmetry. An additional

2

incidental byproduct of the training procedure in Sidman’s (1971) study was that after

training, the participant could also label (D) the pictures (B) and printed words (C).

Over the past four decades, numerous studies have replicated the findings on

equivalence across different populations such as typically developing children (e.g., de

Rose, Hidalgo, & Vasconcellos, 2013), children with autism (e.g., LeBlanc, Miguel,

Cummings, Goldsmith, & Carr, 2003) and adolescents with fragile X syndrome (Hall,

DeBernardis, & Reiss, 2006), using a variety of stimuli (e.g., Arntzen, Halstadtro, Bjerke

& Halstadtro, 2010; Haegele, McComas, Dixon, & Burns, 2011; Keintz, Miguel, Kao, &

Finn, 2011; Miguel, Yang, Finn, & Ahearn, 2009) and distinct training structures (e.g.,

Doughty, Kastner, & Bismark, 2011; Wilson & Hayes, 1996).

Three training structures (Saunders & Green, 1999) typically used in this type of

research are: one-to-many (OTM), many-to-one (MTO), and linear series (LS). With an

OTM procedure, the learner is taught to select different comparison stimuli in the

presence of the same sample stimulus (e.g., AB and AC relations). MTO entails the

selection of the same comparison stimulus in the presence of multiple sample stimuli

(e.g., BA and CA relations). LS describes a procedure in which the comparison stimuli

of the first taught relation (e.g., AB), serves as the sample in the second trained relation

(e.g., BC). The stimulus that is shared between trained relations is known as the node

(Fields & Verhave, 1987). Preliminary studies comparing the relative effectiveness of

the three training structures on the formation of equivalence classes have found OTM and

3

MTO to be equally effective (Smeets & Barnes-Holmes, 2005b), but slightly more

effective than LS (Arntzen, Grondahl, & Eilifsen, 2010).

The cost effectiveness of teaching a small number of relations in a systematic

manner that result in an intricate network of emergent relations has caught the attention

of many behavior analysts. The three main accounts attempting to uncover the

mechanisms underlying the emergence of derived relations are, Sidman’s theory of

equivalence (Sidman, 2000) and its derivation, the stimulus control topography

coherence theory (McIlvane & Dube, 2003), Relational Frame Theory (RFT; Hayes,

1996; Hayes, Barnes-Holmes, & Roche, 2001), and the naming hypothesis (Horne &

Lowe, 1996). Sidman’s account considers the emergence of novel relations to be a

primitive behavioral process wherein all stimuli participating in any three-term

contingency enter into equivalence relations during training. In a visual-visual MTS task,

for instance, given two trials (i.e., three-term contingencies) with identical antecedents,

consequences, and topographically similar responses (e.g., pointing), the two visual

stimuli across the two trials would enter the same equivalence class (see Sidman, 2000

for further details). Alternatively, both RFT and the naming hypothesis suggest that

derived relations are profoundly rooted in verbal behavior, but from different

perspectives. According to the RFT account, contingencies present during language

acquisition form frames of reference that set the stage for emergent relations (see Hayes,

1996). In contrast, the naming hypothesis suggests that language mediates the formation

4

of equivalence classes. For the purpose of this study, only the naming hypothesis will be

discussed in further detail.

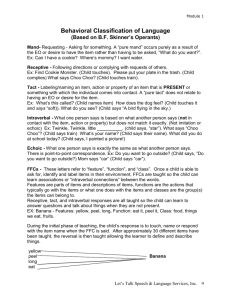

The naming hypothesis extends Skinner’s (1957) interpretive exercise on a

functional analysis of verbal behavior using well-established behavior principles. Horne

and Lowe (1996) defined naming as a generalized operant which entails the bidirectional

relation of an individual responding as a listener to her own speaker behavior. The two

primary components of the naming relation are an elementary verbal operant (i.e., an

echoic, tact, or intraverbal) and conventional (i.e., learned) listener behavior. Horne and

Lowe (1996) described two mechanisms by which equivalence classes are formed,

common naming and intraverbal naming.

Common naming consists of a circular relation between a common tact1 and

conventional listener behaviors. For example, in the presence of a dog, a child overtly or

covertly tacts (i.e., labels) “dog” (speaker behavior), which produces a response product

that serves as a discriminative stimulus (SD) for orienting or pointing to the dog (listener

behavior). Stimuli that are part of the same name relation, evoke identical speaker and

listener behaviors, and hence pertain to the same category. For instance, in a recent study

conducted by Miguel and Kobari-Wright (2013), two children with autism spectrum

disorder between five and six years of age were taught the category name for three

groups of dogs. Pretests required participants to match pictures of dogs based on

1

Skinner (1957) defined a tact as a verbal operant under the control of a nonverbal

antecedent stimulus (e.g., an object, event, or property of one) that is maintained by

generalized reinforcement. An example would be saying “airplane” in the presence of an

airplane in the sky.

5

category membership: hound dog, work dog, or play dog. Neither participant was able to

categorize the nine pictures of dogs prior to tact training. Upon learning to tact each

picture of a dog with its category name, one participant passed the categorization posttest

and the other required additional instruction to tact the sample prior to selecting a

comparison stimulus to be able to categorize. These results suggest that when the second

participant tacted the sample stimulus overtly, she heard herself say the category name

and responded to the auditory stimulus by selecting the comparison stimulus that shared

the same name relation. This interlocking relation between speaker and listener behavior

is what supports common naming as a form of verbal mediation in problem solving tasks.

Similarly, Lowe, Horne, Harris, and Randle (2002), empirically evaluated the role

of common naming on stimulus substitutability using a categorization task with nine

toddlers between the ages of two and four. Six arbitrary stimuli divided into two threemember categories called “vek” and “zog” were used. In the beginning, participants

were taught to tact each of the six stimuli with the category name. Subsequently,

category MTS tests were administered in one of two ways: (1) a sample was presented,

the participant looked at the sample, and then selected the corresponding comparison

stimulus, or (2) a sample was presented, the participant was instructed to tact the sample,

and then selected the corresponding comparison stimulus. Results indicated that by

simply teaching a common tact, either vek or zog, all of the participants were able to

categorize the stimuli into different classes. Additionally, five participants required the

instruction to overtly tact the sample before selecting the comparison stimulus to pass,

6

which is consistent with the findings from Miguel and Kobari-Wright (2013) and with the

role of verbal mediation in the naming hypothesis.

Moreover, Sprinkle and Miguel (2012) compared and contrasted the efficacy of

teaching listener versus speaker behavior on the emergence of equivalence classes with

four children diagnosed with autism between the ages of five and seven. Within an

alternating treatments design, participants were exposed to two sets of stimuli, one

correlated with listener (MTS training) and one with speaker (textual/tact) training. Each

set of stimuli contained three three-member classes (18 stimuli total across sets). Initial

pretests evaluated whether participants could (1) select a picture (B) or printed word (C)

given a dictated name (A), (2) select a picture (B) when shown a printed word (C) and

vice versa (i.e., CB), and (3) orally label (D) a given picture (B) or printed word (C). For

listener training, participants were taught AB and AC relations, meaning that in the

presence of the dictated word (A), to select the corresponding picture (B) or printed word

(C) from the comparison array. During speaker training, participants were taught BD and

CD relations, meaning that in the presence of a picture (B) or printed word (C), engage in

tact or textual behavior (D), respectively. Posttests indicated that while listener training

alone cannot reliably lead to the emergence of speaker behavior and equivalence classes,

exposure to speaker training was sufficient for all participants to derive listener behavior

and equivalence classes. Such results support the notion that both speaker and listener

behavior are necessary for stimulus categorization to emerge (Miguel & Petursdottir,

2009).

7

The role of common naming on arbitrary categorization tasks (e.g., Lowe, Horne,

Harris, and Randle, 2002; Lowe, Horne, & Hughes, 2005; Horne, Hughes, & Lowe,

2006; Horne, Lowe, & Harris, 2007), nonarbitrary categorization tasks (e.g., Miguel,

Petursdottir, Carr, & Michael, 2008), arbitrary matching (Eikeseth & Smith, 1992), and

non-arbitrary matching (e.g., Sprinkle & Miguel, 2012) are well-documented across

typically developing (e.g., Mahoney, Miguel, Ahearn, & Bell, 2011) and developmentally

disabled individuals (e.g., Miguel & Kobari-Wright, 2013). Common naming as a verbal

mediation strategy continues to propel extensive research, with the most recent endeavors

in deciphering complex linguistic phenomenon such as analogical reasoning (e.g.,

Lantaya, Fernand, LaFrance, Dickman, & Miguel, 2013; Quah, Lantaya, Meyer, &

Miguel, 2013).

Another verbal mediation strategy proposed by Horne and Lowe (1996) is

intraverbal naming. With intraverbal naming, the response product of a tact evokes an

intraverbal2 which leads to the individual responding to the final response product as a

listener (Lowe & Horne, 1996), thus creating a verbal rule linking stimuli together

(Dugdale & Lowe, 1990). For example, in the presence of a toothbrush, a child (overtly

or covertly) tacts, “toothbrush” (speaker behavior), which produces a response product

that serves as a verbal SD due to a history of reinforcement or “contiguous usage”

2

An intraverbal is an elementary verbal operant under the control of a verbal

discriminative stimulus, with no formal similarity or point-to-point correspondence

between the two (Skinner, 1957). Examples of intraverbals include answering questions,

responding to emails, engaging in debates, recalling past events, singing a song, and

telling a story. For instance, answering, “Fine” in response to the question, “How are you

doing?” or saying, “Cake” upon hearing, “Birthday.”

8

(Skinner, 1957) for the intraverbal, “toothpaste.” In turn, the intraverbal itself (saying

“toothpaste”) produces yet another response product that serves as an SD for picking up

the toothpaste (listener behavior).

Lowe and Beasty (1987) showed how 29 typically developing children between

the ages of two and five may have utilized intraverbal naming as a mediation strategy for

deriving relations on an MTS task. All MTS tasks employed a two-comparison stimuli

array from the same category (i.e., vertical vs. horizontal lines for line drawings, green

vs. red for colors, and triangle vs. cross for shapes). Initial teaching conditions included

matching a vertical line (A1) to green (B1) and a horizontal line (A2) to red (B2). Then,

participants were taught to relate a vertical line (A1) with a triangle (C1) and a horizontal

line (A2) with a cross (C2). Dependent variables included participants’ spontaneous

vocalizations throughout all training and testing phases and their performance on

symmetry (i.e., B1A1, C1A1, B2A2, and C2A2) and transitivity (i.e., B1C1, C1B1,

B2C2, and C2B2) MTS posttests. Results showed that of the 17 participants that passed

the equivalence posttest, all had intraverbally named the correct sample-comparison pairs

at some point during training. For example, after mastering AB and AC relations, when

presented with B2 as a sample stimulus on a posttest, a participant said, “down red

cross.” In this case, the presence of B2 was strong enough to evoke the tact “down”

which in turn evoked the intraverbal “red cross” and led to the selection of either A2 or

C2 that was present in the comparison array. Lowe and Beasty speculated that selfechoic repetition (Skinner, 1957) may have facilitated the emergence of symmetrical and

9

transitive intraverbal relations. For instance, when repeating, “down red cross down red

cross,” the frequency of “red” (B2) presented before “cross” (C2) may have been

sufficient to establish equivalence relations (i.e., B2C2 and C2B2).

Furthermore, Bentall, Dickins, and Fox (1993) investigated the effects of teaching

class names (i.e., common naming) versus individual names on the emergence of derived

relations. Six three-member classes created with 18 arbitrary stimuli were employed. Of

the 16 undergraduate participants, half received tact training on class names (six verbal

stimuli total) and half on individual names (eighteen verbal stimuli total). Participants

were then exposed to visual-visual MTS training to establish AB and BC relations. Prior

to the start of training, experimenters instructed participants to tact the sample stimulus

when it appeared and the comparison stimulus while selecting it. Upon mastery of AB

and BC relations, experimenters administered a MTS test consisting of trained relations,

symmetry, transitivity, and equivalence. Results indicated that participants who learned

class names made fewer errors on all test relations than participants who learned

individual names. A secondary dependent measure of this study was response latency,

the amount of time between the participant’s overt tact of the sample stimulus and

selection of the comparison stimulus. Compared to participants exposed to class names,

results indicated that participants who received training in individual stimuli names had

longer response latencies on tests of transitivity and equivalence. Bentall and colleagues

speculated that longer response latencies were correlated with nodal distance. That is,

intraverbal naming required two verbal links and one node (e.g., A goes with B, B goes

10

with C, so A goes with C) as opposed to common naming, which only required one

verbal link and no nodes (i.e., the category name) to solve the task. Five of the eight

participants in the individual name group reported creating intraverbal links as a strategy

for solving the derived relations MTS test. During the post-experimental interview, for

instance, one participant stated that given a particular sample stimulus, she “…imagined a

bracelet hung on the tusks, and tusks on a dinosaur” (p. 209). Recent studies that have

determined that visual imaging may facilitate the use of verbal mediation strategies (e.g.,

Kisamore, Carr, and LeBlanc, 2011) provide some insight on interpreting this

participant’s verbal report.

Smeets and Barnes-Holmes (2005a) conducted the first study directly examining

the role of intraverbal naming on equivalence. Using 15 arbitrary stimuli divided into

five three-member classes (i.e., A, B, C, D, and E), 16 typically developing five-year-old

participants were trained on AB and AC relations via visual-visual MTS training and

“N”(dictated name) D and “N”E relations via auditory-visual MTS training. Upon

passing symmetry and equivalence MTS tests (with or without remedial training), a

naming test was conducted to evaluate whether participants assigned an individual or

class name to each stimulus. As a result of the naming test, participants were further

divided into two groups, a “consistent group” with seven participants who tacted stimuli

with the same verbal response reliably (e.g., given the picture of an elephant, saying

“elephant” each time), and an “inconsistent group” with eight participants who tacted

stimuli with a different verbal response across presentations (e.g., given an elephant,

11

saying “car,” “elephant,” or “button” across trials). One participant was not eligible to

continue due to special circumstances. In accordance with intraverbal naming, the

product of tacting the sample stimulus should serve as an SD, evoking an intraverbal that

leads to the selection of the corresponding comparison stimulus. Thus experimenters

hypothesized that participants in the “consistent group” would form equivalence classes

because the same initial tact would reliably evoke the correct intraverbal relation (e.g., in

the presence of an elephant as the sample, tacting “elephant” evoked the intraverbal

“letter” or “wheel” and subsequently selecting the corresponding stimulus from the

comparison array). Conversely, those in the “inconsistent group” would not be able to do

so because random initial tacts would evoke random, unrelated, intraverbal relations (e.g.,

given an elephant as a sample, tacting “car” would evoke the intraverbal “voo,” and lead

to the selection of a comparison stimulus unrelated to the sample). Results showed that

three of seven (43%) and five of eight (63%) participants in the consistent and

inconsistent groups, respectively, passed the equivalence tests. These findings challenge

the intraverbal naming account because children in the inconsistent group were able to

form equivalence classes despite the lack of a reliable initial verbal response (i.e., a tact)

required for verbal mediation. The mixed results led Smeets and Barnes-Holmes to

conclude that naming alone was insufficient for explaining equivalence. A notable

limitation is that experimenters used an explicit naming test which generated rules for

engaging in overt verbal behavior. During a naming test, verbal responses under the

control of a verbal stimulus such as, “What do you call this?” (Smeets & Barnes-Holmes,

12

2005a) may not correspond with verbal responses under the control of variables present

during the experimental condition (e.g., visual stimuli, schedules of reinforcement, etc.;

Lima & Abreu-Rodrigues, 2010). Since verbal behavior in naming tests and

experimental conditions may differ because they are under the control of very different

antecedent stimuli, the accuracy of verbal reports on naming tests with regards to task

performance is questionable (Dugdale & Lowe, 1990; Horne & Lowe, 1996). Therefore,

despite naming tests, it is still unclear whether participants in the study conducted by

Smeets and Barnes-Holmes (2005a) engaged in covert verbal mediation strategies during

posttests.

In a recent unpublished dissertation, Carp (2012) evaluated whether a

combination of tact and visual-visual MTS training would be sufficient for the emergence

of vocal intraverbal relations and the formation of equivalence classes. A total of nine

familiar pictures divided into three three-member categories – states (A), birds (B), and

flowers (C) – were used. Initially, six typically developing kindergarteners were taught

to tact each of the nine stimuli with their common names (e.g., California, quail, poppy)

followed by an intraverbal test assessing the emergence of AB, AC, BA, CA, BC, and CB

vocal intraverbal relations. The intraverbal test was conducted in a question-answer

format. For instance, the experimenter would ask, “California (A3) goes with which

bird?” with the correct answer being “Quail (B3).” In this example, the word “bird”

served as the contextual cue for a vocal response related to category B (i.e., quail) and not

C (i.e., poppy). Subsequently, participants were exposed to visual-visual MTS training in

13

which participants were taught to relate state to bird (AB) and state to flower (AC)

relations. Upon mastery of AB and AC relations, an equivalence test (BC and CB

relations) for emerging visual-visual relations and a second intraverbal test were

administered. Results indicated that only two participants passed the equivalence test

following visual-visual MTS training, one participant passed after remedial training, and

three participants never passed, even with extensive remedial training. Furthermore, the

three participants who passed the equivalence test continued on to pass the intraverbal

test and the three participants who failed the equivalence test also failed the intraverbal

test. Such results are consistent with intraverbal naming because it is possible that

contingencies during training (i.e., reinforcement during MTS training) facilitated the

emergence and establishment of intraverbal relations that later mediated performance on

derived relations tests (Horne & Lowe, 1996). For example, given a picture of California

(A3) as the sample stimulus, participants covertly or overtly tacted, “California,” and

when shown the comparison stimuli, tacted “quail” (B3) or “poppy” (C3) while making a

selection. Although reinforcement was provided contingent upon selecting (i.e., pointing

to) the correct comparison stimulus, it also inadvertently strengthened any covert or overt

spontaneous verbal behavior that was occurring simultaneously. In this case,

reinforcement following the correct selection of a comparison stimulus also reinforced

any verbal behavior that may have been occurring concurrently with the selection

response, such as, “California (A3) – quail (B3)” and/or “California (A3)” – poppy (C3).”

In turn, due to self-echoic repetition (e.g., “California poppy California quail California

14

poppy California quail”), these intraverbal relations may have facilitated the emergence

of “quail (B3) – poppy (C3)” and “poppy (C3) – quail (B3)” (i.e., transitive relations) due

to contiguous usage (Skinner, 1957).

While previous studies demonstrated a correlation between intraverbal and

derived relations, they could not definitively conclude that participants engaged in

intraverbal naming as a form of verbal mediation. Bentall et al. (1993) and Carp (2012)

suggested that the most direct way to assess the role of intraverbal naming is to teach the

intraverbal relation and assess how participants perform on an MTS posttest where

stimuli are only intraverbally (i.e., arbitrarily) related. Thus, Santos, Ma, Jennings, Zias,

and Miguel (2013) conducted a study evaluating the exclusive role of intraverbal naming

on an arbitrary MTS task with undergraduate students. In Experiment 1, eighteen

arbitrary stimuli, each with an assigned Tagalog exemplar name, were divided into three

sets of six arbitrary stimuli with each set composed of two three-member categories.

Matching-to-sample pretests showed that all six participants were unable to match stimuli

from category A to category B based on experimental relations. Teaching conditions

aligned closely with the components required for using intraverbal naming as a verbal

mediation strategy on MTS tasks – tact, intraverbal, and listener behavior. The purpose

of tact training was to teach participants to say the name of each individual stimulus (e.g.,

manok, anim, ibon) and to establish each stimulus as a nonverbal SD. Listener testing

evaluated whether participants could select a comparison stimulus conditional upon a

dictated name. During intraverbal training, experimenters taught participants

15

unidirectional AB intraverbal relations in statement format using the autoclitic “___ goes

with ___” (e.g., Manok goes with Ibon) in the absence of visual stimuli. Upon meeting

mastery criteria for each condition, all six participants passed the AB MTS posttest,

which required them to match arbitrary stimuli solely based on the learned experimental

intraverbal relations. Furthermore, two of the participants overtly emitted the intraverbal

relation during posttests without having been explicitly instructed to do so.

In Experiment 2, four undergraduate students, one from the previous study (P6)

and three new recruits were probed for the emergence of symmetrical intraverbal

relations and corresponding stimulus-stimulus relations (i.e., MTS performance). P7, P8,

and P9 were only exposed to training procedures for one set of stimuli, as opposed to

three sets for P6 (due to participation in Experiment 1). The same set of stimuli was used

across participants to evaluate derived relations. Following training conditions and the

final AB MTS posttest, P6 and P7 were exposed to a BA intraverbal posttest and then a

BA MTS posttest. For P8 and P9, the order of the tests was reversed so that the BA MTS

posttest was administered before the BA intraverbal posttest. P8 passed the BA MTS

posttest, but failed the BA intraverbal posttest and spontaneous vocalization data showed

that inaccurate performance was correlated with the absence of overt vocalizations. The

remaining three participants passed the posttests, demonstrating the emergence of

symmetrical intraverbal and stimulus-stimulus relations. These findings suggest that tact

and intraverbal training alone may be sufficient to establish symmetrical intraverbal and

stimulus-stimulus relations.

16

Provided that preliminary data on the role of intraverbal naming on derived

symmetry relations is promising (Santos et al., 2013), and that teaching efficacy increases

as a function of equivalence class formation and expansion (Sidman & Tailby, 1982), the

next logical step would be to assess the role of intraverbal naming on transitivity and

equivalence relations. Therefore, the purpose of the following two experiments is to

evaluate the effects of teaching unidirectional intraverbal relations in a statement format

on (1) the emergence of symmetrical (i.e., bidirectional) and transitive intraverbal

relations, and (2) the formation of equivalence (stimulus-stimulus) classes.

17

Chapter 2

EXPERIMENT 1

Method

Participants

Participants included eight undergraduate students from California State

University, Sacramento (CSUS), 2 males (P2 and P3) and 6 females (P1, P4, P5, P6, P7,

and P8) between the ages of 21 and 34. Prior to the start of the study, participants were

asked to complete a demographics survey including the following information: gender,

age, grade point average, and primary language (see Table 1). Individuals who

participated in any prior stimulus equivalence studies were excluded. Participants were

required to attend one 2.5-hour session with a 5-minute break offered after completing

each condition (e.g., after pretests, after meeting mastery criteria for tact training, etc.),

for a maximum of five breaks per session. Participants received extra credit for an upperdivision college-level psychology course upon completion of the study.

18

Table 1

Participant Demographics

Participant

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

Gender

F

M

M

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

M

F

F

Age

21

24

30

22

34

22

22

31

30

25

23

23

31

24

GPA

2.6

N/A

3.8

3.5

3.4

2.3

3.7

3.0

3.2

3.0

3.0

3.4

2.6

3.3

Primary Language

English

English

English

English

English

English

English

English

English

English

English

English

Tagalog

English

Setting and Materials

All experimental sessions were conducted at the Verbal Behavior Laboratory at

CSUS. The room measured 7 x 3 m, and included several tables and office chairs, two

desktop computers, two vertical filing cabinets, and a bookshelf.

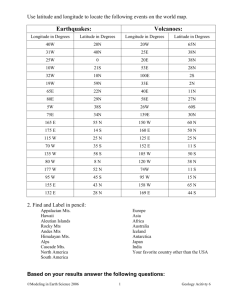

Stimuli consisted of nine common images (similar to Carp, 2012), further divided

into three categories – birds (A), states (B), and flowers (C) (see Figure 1), with three

members each (i.e., A1, A2, A3, B1, B2, B3, C1, C2, and C3). For intraverbal and MTS

tasks, cross set stimuli with the same number were considered a correct match (e.g., A1

and B1) and those with a different number, an incorrect match (e.g., B2 and C1). Target

intraverbal relations are shown in Table 2. The letter-number code (e.g., A3) assigned to

each stimulus was for the experimenter’s use only; participants were not exposed to these

19

codes. All stimuli were presented via the computer program, Mestre Libras (Elias,

Goyos, Saunders, & Saunders, 2008) on a 15-inch LCD computer screen.

[A1] Cardinal

[A2] Yellowhammer

[A3] Mockingbird

A1

A2

A3

[B1] Virginia

[B2] Alabama

[B3] Texas

B1

B2

B3

[C1] Dogwood

[C2] Camellia

[C3] Bluebonnet

C1

C2

Figure 1. Experimental stimuli.

C3

20

Table 2

Target Intraverbal Relations

Antecedent Stimuli

Baseline

A B Bird State

The state for [A1] is…

[A1] Cardinal

The state for [A2] is…

[A2] Yellowhammer

The state for [A3] is…

[A3] Mockingbird

Correct Response

[B1] Virginia

[B2] Alabama

[B3] Texas

B C State Flower

The flower for [B1] is…

The flower for [B2] is…

The flower for [B3] is…

[B1] Virginia

[B2] Alabama

[B3] Texas

[C1] Dogwood

[C2] Camellia

[C3] Bluebonnet

Symmetry

B A State Bird

The bird for [B1] is…

The bird for [B2] is…

The bird for [B3] is…

[B1] Virginia

[B2] Alabama

[B3] Texas

[A1] Cardinal

[A2] Yellowhammer

[A3] Mockingbird

C B Flower State

The state for [C1] is…

The state for [C2] is…

The state for [C3] is…

[C1] Dogwood

[C2] Camellia

[C3] Bluebonnet

[B1] Virginia

[B2] Alabama

[B3] Texas

Transitivity

A C Bird Flower

The flower for [A1] is…

The flower for [A2] is…

The flower for [A3] is…

[A1] Cardinal

[A2] Yellowhammer

[A3] Mockingbird

[C1] Dogwood

[C2] Camellia

[C3] Bluebonnet

C A Flower Bird

The bird for [C1] is…

The bird for [C2] is…

The bird for [C3] is…

[C1] Dogwood

[C2] Camellia

[C3] Bluebonnet

[A1] Cardinal

[A2] Yellowhammer

[A3] Mockingbird

For each testing and training condition, predetermined blocks consisting of a set

number of trials were presented to ensure that stimuli were presented in counterbalanced

21

order to eliminate potential biases (e.g., side bias, exposure, etc.; Green, 2001). Sample

stimuli varied unsystematically across trials so that each sample was presented three

times within an 18- or 27-trial block. Comparison stimuli were programmed so that (1)

comparison arrays consisted of three stimuli per trial, (2) the position of comparison

stimuli varied across trials, and (3) the position of the correct comparison stimulus per

sample stimulus appeared in the left, middle, and right positions one time each across

three trials within a block. For example, in a MTS block, given A1 as a sample stimulus,

B1 appeared on the left for one trial, middle for another, and right for the last, with A2

and A3 serving as sample stimuli for trials interspersed in between. Each sample

stimulus was presented three times during 27-trial blocks for tact training and listener

testing and training, and 18-trial blocks for intraverbal training and testing, and MTS

tests. Two patterns of 18- and 27-trial blocks were presented in randomized order to

control for repeated exposure. See Appendix A-F for trial order on data sheets.

Response Measurement

Dependent Variables. For tact and intraverbal training, the dependent variable

was the percentage of correct unprompted vocal responses (e.g., for a tact trial, when

shown a picture of cardinal [A1], participants said “cardinal [A1],” and for an intraverbal

trial, given the fill-in-the-blank statement “The state for cardinal [A1] is…,” participants

said “Virginia [B1]”). During listener testing and training, performance was measured as

the percentage of correct unprompted selection of a comparison stimulus from a threestimuli array conditional upon the dictated name of a sample stimulus (e.g., when the

22

computer program said “Cardinal [A1],” participants selected the picture of the cardinal

[A1] and not the yellowhammer [A2] or mockingbird [A3]). Three variables were

measured during MTS test conditions, (1) the percentage of correct unprompted

comparison stimulus selection in the presence of a given sample stimulus (e.g., given

cardinal [A1] as a sample, selecting Virginia [B1] and not Alabama [B2] or Texas [B3]),

(2) response latency, the amount of time in seconds between the presentation of the

comparison array and the selection of a comparison stimulus (Bentall et al., 1993;

Dymond and Rehfeldt, 2000), and (3) participants’ spontaneous vocalizations (i.e.,

anything participants overtly say that was not specified by the experimenter).

Data Collection. Participants were seated in front of a computer screen and next

to the primary experimenter to avoid experimental cueing. The wall behind the computer

screen was unadorned. An Apple iPad 2 © was propped up to the right of the participant

and experimenter for recording purposes. A trained observer sat behind participants and

the experimenter to collect data. The trained observer recorded correct unprompted (+),

prompted (P), incorrect responses (-), and spontaneous vocalizations in vivo for all

training and testing sessions. To avoid the possibility of incidentally reinforcing

participants’ chaining of incorrect and correct responses together (e.g., “self-correction”),

the participants’ first response was used to determine if the response was correct or

incorrect. For instance, if participants answered, “Texas, I mean Virginia” during a tact

training trial, “Texas” was used. For all conditions, participants were required to respond

within 5 s of the presentation of the sample stimulus, with the exception of intraverbal

23

and MTS tests, which was 10 s (Santos et al., 2013). The purpose of increasing the

amount of time participants had to respond during test conditions was to assess whether

longer response latencies were correlated with nodal distance (Bentall et al., 1993).

Responses which were no nodes apart (i.e., AB, BC, BA, BC) should have equal response

latencies that are shorter than those for responses which are one node apart (i.e., AC,

CA). The final percentage for any given block was calculated as follows: number of

correct unprompted (+) responses divided by the total number of trials. The software

digitally recorded correct and incorrect responses for MTS and listener tests as well as

response latency. The trained observer collected data on intraverbal training and testing,

and spontaneous vocalizations during the AC/CA MTS vocal posttest.

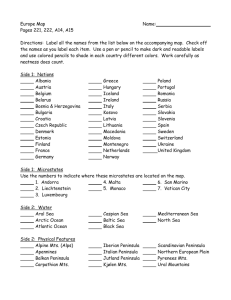

Experimental Design

A two-tier non-concurrent multiple baseline design across participants (Watson &

Workman, 1981) was used to evaluate the emergence of derived relations. As shown in

Figure 2, four participants (P1, P2, P5, and P6) were exposed to the following conditions:

pre-training, MTS pretest, tact training, listener testing, AB/BC intraverbal training,

training review, AB/BC MTS posttest, BA/CB intraverbal testing, BA/CB MTS posttest,

remedial symmetry training (if needed), AC/CA intraverbal testing, and AC/CA MTS

posttest. Remedial training for failing listener testing and MTS posttests were designed

but were not evaluated because all participants meeting the passing or emergence criteria

(see Appendix G). For the other four participants (P3, P4, P7, and P8), the order of

conditions were identical with the exception that for the BA/CB (symmetry) and AC/CA

24

(transitivity) posttests, the corresponding MTS posttests will be conducted prior to the

intraverbal test (e.g., BA/CB MTS posttest before BA/CB intraverbal test) as specified in

Figure 3. Mastery, passing, and emergence criteria for each condition are presented in

Table 3.

Figure 2. Sequence of training and testing conditions for P1, P2, P5, and P6. Arrows and

boxes with dashed lines represent conditions that will be conducted if participants fail to

meet the passing criteria for the preceding condition. Arrows and boxes with solid lines

represent standard conditions.

25

Figure 3. Sequence of training and testing conditions for P3, P4, P7, and P8. Arrows and

boxes with dashed lines represent conditions that will be conducted if participants fail to

meet the passing criteria for the preceding condition. Arrows and boxes with solid lines

represent standard conditions.

26

Table 3

Passing, Mastery, and Emergence Criterion for Each Condition

Condition

1

Targets

per block

Trials per

block

Number of attempts

Pre-training

1 (P1, P3, P5, P7)

2 (P2, P4, P6, P8)

Criterion

3 consec.

correct

< 50%

MTS Pretest

6

18

2

Tact Training

9

27

N/A

1 block 100%

3

Listener Testing

9

27

2

1 block 100%

Listener Training

9

27

N/A

1 block 100%

4

AB/BC Intraverbal Training

6

18

N/A

1 block 100%

5

Review

N/A

Tact

9

27

N/A

1 block 100%

Listener

9

27

N/A

1 block 100%

AB/BC Intraverbal

6

18

N/A

1 block 100%

AB/BC MTS Posttest

6

18

2

1 block >89%

Remedial Phase 1

9

9

N/A

1 block 100%

Remedial Phase 2

9

9

N/A

1 block 100%

Remedial Phase 3

3

9

N/A

1 block 100%

7

BA/CB Intraverbal Testing

6

18

2

1 block >89%

8

BA/CB MTS Posttest

6

18

2

1 block >89%

Remedial Phase 1

3

9

N/A

1 block 100%

Remedial Phase 2

3

9

N/A

1 block 100%

9

AC/CA Intraverbal Testing

6

18

2

1 block >89%

10

AC/CA MTS Posttest

6

18

2

1 block >89%

Remedial Phase 1

3

9

N/A

1 block 100%

Remedial Phase 2

3

9

N/A

1 block 100%

AC/CA MTS Vocal Posttest

6

18

1

1 block >89%

6

11

Interobserver Agreement (IOA)

A second observer collected data from digital video recordings for 50% of each

condition in which Mestre Libras did not record responses (i.e., tact training, and

27

intraverbal training and testing) for IOA purposes. An agreement for each trial is defined

by both observers scoring the trial as correct unprompted, prompted, or incorrect.

Discrepancies between observers were scored as a disagreement. Point-by-point

percentage of agreement was calculated using the following formula: total number of

agreements divided by total number of agreements plus disagreements and then

multiplied by 100. Each participants’ mean IOA percentage and range across conditions

are shown in Table 4.

Table 4

Interobserver Agreement and Treatment Integrity Across Participants.

P1

P2

P3

P4

P5

P6

P7

P8

P9

P10

P11

P12

P13

P14

Interobserver Agreement

Mean

Range

99.3

97.6-100

100

100-100

98.1

88.8-100

100

100-100

97.7

88.9-100

100

100-100

100

100-100

99.1

94.4-100

97.2

88.8-100

99.3

97.2-100

100

100-100

100

100-100

100

100-100

100

100-100

Treatment Integrity

Mean

Range

99.6

94.4-100

99.3

90.2-100

100

100-100

99.2

88.8-100

100

100-100

99.8

97.8-100

99.7

96.2-100

99.4

94.4-100

99.2

94.4-100

99.5

94.4-100

100

100-100

100

100-100

100

100-100

100

100-100

Treatment Integrity (TI)

The second observer also assessed TI for 50% of sessions across conditions. Data

were collected on the correct implementation of each trial, including: (1) the timing of

prompts (e.g., no delay vs. after 5-seconds), and (2) the delivery of consequences (e.g.,

28

after every response or none). The trial was coded as incorrect if either of these

components were implemented incorrectly or omitted. Treatment integrity across

conditions was calculated by dividing the number of correctly executed trials by the total

number of trials across conditions and multiplied by 100. Means and ranges for TI for

individual participants are included in Table 4.

Procedures

Pre-training. The purpose of this condition was to familiarize participants with

the different training procedures and computer program. Six familiar stimuli (see Figure

4) not related to those of the study, divided equally into two categories were used for this

condition only. Practice trials for tact training, listener testing, intraverbal training (see

Table 5) and MTS tests were conducted separately until participants reached three

consecutive correct unprompted responses on each task. The procedures for each

condition are described in detail below using experimental stimuli in place of familiar

stimuli.

29

[A1] Pig

[A2] Elephant

[A3] Cat

A1

A2

A3

[B1] Orange

[B2] Banana

[B3] Apple

B1

B2

Figure 4. Pre-training stimuli.

B3

Table 5

Pre-Training Target Intraverbal Relations

Antecedent Stimuli

A B Animal Fruit

The fruit for [A1] is…

[A1] Pig

The fruit for [A2] is…

[A2] Elephant

The fruit for [A3] is…

[A3] Cat

Correct Response

[B1] Orange

[B2] Banana

[B3] Apple

MTS pre- and posttests. The purpose of this condition was to determine

whether participants could match the stimuli shown in Figure 1 based on the intraverbal

relations listed in Table 2. The experimenter read the following instructions to

participants prior to the start of the condition:

In this condition, you will be shown a blank screen with a blue box

positioned at the top left corner. Click on the box and a picture will

appear. Then click on the picture and three pictures will appear

underneath it. I want you to click on the picture on the bottom row that

best matches the picture at the top. You will have 10-seconds to respond

after the pictures appear across the bottom of the screen and the first

30

picture you click will be recorded as your answer. I will not be giving you

any feedback at this point. Do you have any questions?

Each trial began with participants using the mouse to click on a blue box at the

top left corner of the screen (the observing response) for a visual stimulus to appear (e.g.,

cardinal [A1]) on the top right corner. Participants then clicked on the stimulus (the

observing response). Subsequently, three pictures appeared across the bottom of the

screen (e.g., Virginia [B1], Alabama [B2], and Texas [B3]). Participants had 10 s to

respond once comparison stimuli appeared before the experimenter prompted, “Please

make a selection.” There were no programmed consequences following correct or

incorrect responses. Upon selecting a comparison stimulus by using the mouse to click

on it, a blank screen with a blue box at the top left corner appeared, signaling the start of

the next trial. For the pretest, six relations were tested: (1) bird to state (AB), and (2)

state to flower (BC), (3) state to bird (BA), (4) flower to state (CB), (5) bird to flower

(AC), and (6) flower to bird (CA). The AB/BC relations served as baseline relations and

participants were directly trained on these two relations. Posttests assessed for the

emergence of BA/CB symmetry relations and AC/CA transitivity relations and were

conducted in the orders specified in Figures 2 and 3. Sessions were conducted in 18-trial

blocks in which each of the six sample stimuli were presented three times with the

corresponding comparison stimulus presented one time each in the left, middle, and right

positions.

For the pretest, the criterion for continuing to the next condition was one to two

18-trial blocks with 50% or less of correct responses. For posttests, participants were

31

given two attempts (i.e. two blocks) to meet the passing or emergence criteria, so that if

participants failed the first block, a second block was presented. If participants also

failed the second block, then remedial training was implemented. The passing criterion

for AB/BC relations and emergence criteria for BA/CB and AC/CA relations was set at

one 18-trial block with 16 out of 18 trials (89%) of correct responding.

If P1, P2, P5, and P6 failed to meet the passing or emergence criterion for BA/CB

and AC/CA MTS posttests, the experimenter directly taught participants the

corresponding intraverbal relations that were presented in the preceding intraverbal test

condition (see Appendix G). However, if P3, P4, P7, and P8 failed to meet the passing or

emergence criterion for BA/CB and AC/CA relations, they continued to the

corresponding intraverbal test. Failure to meet the emergence criterion for the

subsequent intraverbal test resulted in remedial training as specified for the

corresponding MTS task (see Appendix G). For example, if a participant scored 67% and

50% on two consecutive blocks of BC/CA MTS and proceeded to score 33% on the

following BC/CA intraverbal test, then remedial training for BC/CA relations was

conducted. Nonetheless, if a participant met emergence criteria for the intraverbal test,

the corresponding MTS posttest was repeated and if he or she still failed, remedial

training was implemented.

The terminal condition for each participant was one 18-trial block of AC/CA

MTS vocal posttest. Prior to the start, the experimenter read the following instructions to

participants:

32

For this last condition, I want you to think out loud so that we know what

your thought process is as you are solving the task. The rest of the

condition will be identical to the previous matching conditions with 10seconds to respond and no feedback until the very end. Do you have any

questions?

The emergence criteria was set at one 18-trial block with 16 out of 18 trials (89%) of

correct responding regardless of vocalizations emitted.

Tact training. The purpose of this condition was to teach participants to label

each of the nine stimuli when presented successively. Prior to this condition, the

experimenter read the following instructions to participants:

In this condition, you will be shown a blank screen with a blue box

positioned at the top. Point to the box with your finger and after I click on

the box with the mouse, a picture will appear. I want you to tell me what

you see. In the beginning, I will help you by saying the name of the

picture and having you repeat after me. Then, I will let you label the

picture as best as you can. You will have 5-seconds to respond after the

picture appears and your first answer will be recorded as your response. I

will give you feedback on correct and incorrect answers to help you along

the way. Do you have any questions?

After participants pointed to the blue box (the observing response) located at the

top of the computer screen, the experimenter clicked on the blue box and a visual

stimulus appeared. Initially, a zero-second delay echoic prompt was provided upon the

presentation of a stimulus, where the experimenter said the name for participants to

repeat. After the first nine-trials of the first block, a constant 5-second prompt delay

(Ingvarsson & Hollobaugh, 2011) was implemented for the remaining 18 trials and all

subsequent blocks. Participants had the opportunity to respond independently within the

5-second interval before the experimenter’s echoic prompt. The experimenter provided

33

praise for all correct unprompted responses. If participants responded incorrectly, the

experimenter said, “Try again. Cardinal (A1). What is it?” had participants repeat the

answer, and re-presented the trial. Following the first correct unprompted response, the

experimenter only provided praise for all subsequent correct unprompted responses and

not prompted responses (Karsten & Carr, 2009). Sessions were conducted in 27-trial

blocks in which each of nine sample stimuli were presented three times in predetermined

random order. The mastery criterion for proceeding to the next condition was one 27trial block with 27 out of 27 trials (100%) of correct responding.

Listener testing. The purpose of this condition was to assess how accurately

participants can select a comparison stimulus from a three-stimulus array upon hearing a

dictated name. The experimenter read the following instructions to participants at the

beginning:

In this condition, you will be shown a blank screen with a blue box positioned at

the top left corner. Click on the blue box and a white box will appear and the

program will say a name. Then click on the white box and three pictures will

appear beneath it. I want you to click on the picture on the bottom row that best

matches the name that you heard. You will have 5-seconds to respond after the

pictures appear across the bottom of the screen and the first picture you click will

be recorded as your answer. I will provide you with feedback at the end of this

task. Do you have any questions?

Each trial began with participants using the mouse to click a solid blue box

presented on the top left corner of the computer screen. A white box appeared on the top

right corner and Mestre Libras dictated the name of a target stimulus. Subsequently,

participants clicked on the white box (the observing response) and three pictures

appeared across the bottom of the screen. Participants were given 5-seconds to respond

34

and there were no programmed consequences for correct or incorrect responses. Sessions

were conducted in 27-trial blocks in which each of nine sample stimuli were presented

three times and the corresponding comparison stimulus presented one time each in the

left, middle, and right positions. Participants were given two attempts to meet the

passing criterion, which was set at one 27-trial block with 27 out of 27 trials (100%) of

correct responding. Failure to pass listener testing resulted in listener training (see

Appendix G).

Intraverbal training. The purpose of this condition was to teach participants

intraverbals which established the relations between two stimuli from different classes.

Target intraverbal relations are presented in Table 2. Blocks contained mixed AB and

BC relations, with each relation targeted three times.

For the first block, the experimenter read the following instructions to

participants:

In this condition, I will say a complete statement for you to repeat. Once

you repeat the statement, I will give you with a fill-in-the-blank statement

to complete. You will have 5-seconds to respond and your first response

will be recorded. I will give you feedback on correct and incorrect

answers to help you along the way. Do you have any questions?

Each trial began with the experimenter modeling a statement (i.e., a prompt) for

participants to repeat. Once participants repeated the statement, the experimenter

presented the same statement in a fill-in-the-blank format and gave participants 5-seconds

to complete it. For example, the experimenter said, “The state for cardinal (A1) is

Virginia (B1)” and participants echoed, “The state for cardinal (A1) is Virginia (B1).”

35

Subsequently, the experimenter said, “The state for cardinal (A1) is…” and waited 5seconds for participants to respond. Praise was provided for correct responses and the

second observer recorded it as a prompted (P) response. Following an incorrect response,

the second observer marked the trial as incorrect (-) and the experimenter implemented

an error correction procedure by saying, “Try again,” stating the correct answer, and

repeating the trial. For instance, “Try again. Virginia (B1). The state for cardinal (A1)

is…”

Starting with the second block, trials consisted of fill-in-the-blank statements

only. The experimenter told participants:

Now, I will no longer model the statement beforehand. I will just give you

the fill-in-the-blank statement and I want you to finish it to the best of

your ability. You will have 5-seconds to respond and your first answer

will be recorded. I will give you feedback on correct and incorrect

answers to help you along the way. Do you have any questions?

For example, the experimenter only said, “The state for cardinal (A1) is…” and

gave participants 5-seconds to respond. If participants responded correctly praise was

provided. If participants responded incorrectly, the experimenter stated the correct

response, and immediately re-presented the trial.

Sessions were conducted in 18-trial blocks with each of the six target relations

presented three times. The mastery criterion for moving to the next condition was one

18-trial block with 100% of correct responding.

Review. The purpose of this condition was to ensure participants maintained

accurate responding of trained skills in the absence of programmed consequences. The

36

review condition made sure that performance on posttests could not be attributed to

sudden changes in the schedule of reinforcement (e.g., ratio strain; Baum, 1993).

The review phase included a minimum of one 27-trial block of listener, two18trial blocks of intraverbal, and two 27-trial blocks of tact, with trials within a block

counterbalanced as mentioned in the corresponding sections. The listener, tact, and

intraverbal sequence was fixed to eliminate the possibility of presenting tact, intraverbal,

then listener, as this is the sequence of behaviors that participants needed to engage in

during posttests if they used intraverbal naming as a mediation strategy. The first block

of tact and intraverbal review were divided into three equal segments (i.e., 3 6-trial

segments for 27-trial blocks, and 3 6-trial segments for 18-trial blocks, respectively) so

that the probability of reinforcement for the first third of the trials is 100%, the second is

50%, and the last is 0%. This fading procedure was not applied to the listener review

because listener testing was initially conducted in the absence of reinforcement and hence

reinforcement did not need to be faded. If responding in the first block was maintained at

100% correct responding for tact and intraverbal, a second block was administered in the

absence of programmed consequences. Error correction (i.e., echoic prompt and

repeating the trial) was provided for each incorrect response. The criterion for moving to

the next condition, AB/BC MTS posttest, was set at one 18-trial block at 100% correct

responding for the intraverbal review and one 27-trial block at 100% of correct

responding for each listener and tact reviews with no reinforcement.

37

Intraverbal testing. This condition was conducted in the same manner as

intraverbal training, with the exception of no programmed consequences or error

correction procedures, and participants were given 10-seconds to respond after the

experimenter presented the fill-in-the-blank statement. The two relations tested were (1)

BA/CB (symmetry), and (2) AC/CA (transitivity), in the order specified in Figures 2 and

3. Participants were given up to two attempts (i.e., two blocks) to meet the emergence

criterion. Sessions were conducted in 18-trial blocks and each of the six target relations

were presented three times in an unsystematic manner. There was no passing criterion

for intraverbal tests and participants proceeded to the corresponding MTS task (P1, P2,

P5, and P6) or necessary remedial training (P3, P4, P7, and P8) after up to two 18-trial

blocks of intraverbal testing. Upon completing BA/CB intraverbal testing, P1, P2, P5,

and P6 moved on to the BA/CB MTS posttest and P3, P4, P7, and P8 moved on to

remedial training or proceeding MTS posttest regardless of performance on the

intraverbal test. The emergence criterion for intraverbal relations was set at one 18-trial

block with 16 out of 18 trials (89%) or higher of correct responding (Carp, 2012).

Results and Discussion

P1 and P2

Figure 5 depicts the percentage of correct responses across MTS pre- and

posttests, listener tests, and intraverbal tests for P1 (top panel) and P2 (bottom panel). P1

performed below chance level (50%) for all MTS pretests, AB/BC (22%), BA/CB (39%),

and AC/CA (33%). She reached the mastery criterion for tact training after three blocks

38

(81 trials) and continued on to pass the listener test (100%) on the first block (27 trials).

Subsequently, she met the mastery criterion for intraverbal training after six blocks (108

trials). During the review, she needed one block (27 trials) of listener, two blocks (54

trials) of tact, and two blocks (36 trials) of intraverbal. In the posttest phase, she met

passing or emergence criterion on the first block for the AB/BC MTS (100%), BA/CB

intraverbal testing (94%), BA/CB MTS (100%), AC/CA intraverbal testing (100%), and

AC/CA MTS (89%), in this order. Additionally, she passed the AC/CA MTS vocal

posttest (100%) by correctly tacting stimuli or emitting an intraverbal relation relevant to

the stimuli presented for each trial (100%) of the block. There were no significant

differences in latency for AB/BC, BA/CB, and AC/CA MTS posttests in terms of (1)

averages for each test (M = 2.53 s, M = 2.05 s, and M = 2.58 s, respectively), (2) cross

test first trial performance (3.03 s, 2.68 s, and 2.40 s, respectively), and (3) across trials

within the first block (see Figure 6).

39

Figure 5. Results for P1 on top panel and P2 on bottom panel. The solid diamond,

square, and triangle represent the AB/BC, BA/CB, and AC/CA MTS tests, respectively.

The solid circle refers to the listener test. The “X” stands for the BA/CB intraverbal test

and the asterisk for the AC/CA intraverbal test.

40

Figure 6. Response latency in seconds across 18 trials of the first block of each MTS

posttest for P1. The diamond, square, and triangle represent the AB/BC, BA/CB, and